Ali Ahmadu can only hope the news he had concerning the ceasefire, or peace deal, between the Boko Haram sect and the federal government turned out to be true. And if it is, for him and the people of his village near Michika in Adamawa State could heave a sigh of relief that for once in an excruciating long while, they can sleep in peace. Peace that has eluded them for a long time; when anxiety, fear, trepidation and most times, violent deaths have become their lot.

On Friday, apparently answering the prayers of the likes of Ahmadu, Alex Badeh, an air chief marshall and chief of defence staff, issued an order informing all service chiefs “to comply with the ceasefire agreement between Nigeria and Boko Haram in all theatre of operations”. The kidnapped Chibok schoolsgirls are also to be released.

The Saudi Arabia angle

Earlier, one Danladi Ahmadu, who claimed to be the secretary-general of Boko Haram, informed the Voice of America, VOA, that truly a ceasefire agreement had been reached. Words had indeed earlier filtered out that the terrorist group and the federal government had been meeting in Saudi Arabia, instanced by the Chadian President, Idris Deby. Part of the talks was said to have focused on the release of over 200 girls abducted by the sect on April 14 this year in Chibok, Borno State.

A death before deaths

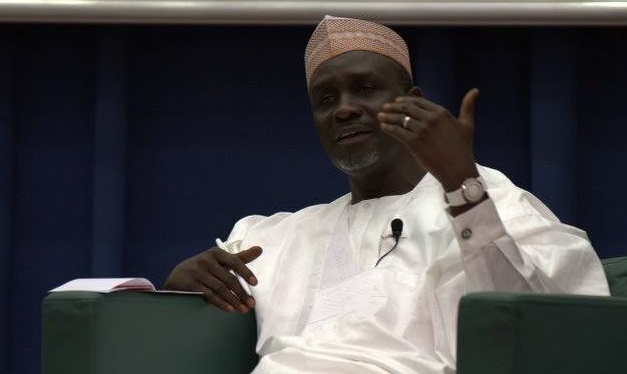

The road to this ceasefire, if truly there is one, is laced with pains, blood, denials, official laid-back approach as well as anguish for the families of those who have lost loved ones in this needless bloodletting. It all started with Mohammed Yusuf, an orator. As his ‘ministry’ grew so was his followership. The authorities became jittery and worried, and understandably so.

Advertisement

After brushes with the law, Yusuf was arrested and in bizarre manner, he was extra-judicially killed. If those who killed Yusuf thought his death would mark the end of his menace, they were wrong. The bomb blast at a Mammy Market in Abuja in late 2010 preceded by the one in Suleja signposted the arrival of terrorism in the country with a devastating efficiency.

UN House as tragic landmark

In August 2011, a bomb blast ripped through the United Nations building in Abuja, which finally but menacingly informed anyone who felt that he was insulated from the problem that it might be so after all. Before then, Hafiz Ringim, then police inspector-general, escaped death by the whiskers as a car loaded with improvised explosive device (IED) exploded and consumed both lives and properties.

In December that year, Madallah, a sleepy town in Niger State, had its Christmas turned to sorrow as parishioners at Saint Theresa’s Catholic Church and passers-by alike were sent to early grave as messengers of death visited the church. In February 2012, it was the turn of Kano. Bombs went off simultaneously and by the time the body bags were counted, over hundred had laid dead.

Advertisement

Could anyone forget the Nyanya bombings close to Abuja in March this year? Or Wuse, Abuja shopping mall own in July this year? Or the Chibok abductions of April this year?

Negotiating with ghosts

In all this, the federal government had always vowed that it would not negotiate with a terrorist group under any guise because nobody was coming forward to state their grievances or speak for the group. “We cannot negotiate with ghosts,” President Goodluck Jonathan said, even when some Nigerians had told the government that it might really not have anything to lose if it did. But the government would not budge. It looked like a peace deal would never materialise.

Territorial battle

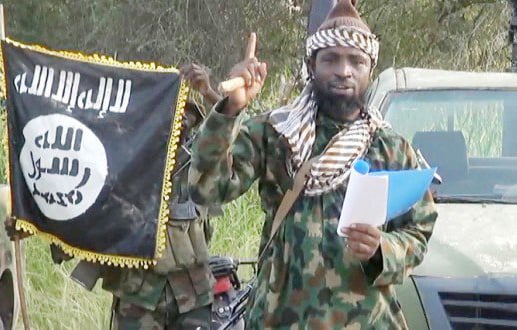

However, with each passing day, Boko Haram’s ‘ground battle’, away from throwing bombs, became more and more devastating. Their acquisition of sophisticated weapons, like rocket launchers, armoured tanks and others like that beyond the ‘ordinary’ AK-47 its foot soldiers were carrying ‘convinced’ even the most optimistic in government circles that the nation had a war in her hands. In fact, from their small fire arms, they became capable of bringing down fighter jets.

Chibok Schoolgirls

Boko Haram began to draw global attention to itself when, on the eve of April 14, 2014, its foot soldiers kidnapped over 200 girls from Government Day Secondary School, Chibok. The girls were writing their final exams when the militants struck. Even though they had been kidnapping women in the past, the sheer number, and the fact that these were teenagers in school, changed the story forever. The whole world began to ask that the girls be brought back.

Advertisement

Jonathan too had been roundly criticised for his slow response to the kidnapping of the Chibok Girls. The campaign that followed, Bring Back Our Girls, seemed to focus more on government than the terrorist group that kidnapped these girls.

The ceasefire is long overdue. And if it happens to work, the likes of Ahmadu and a psychologically traumatised populace, especially along the North-east axis can heave a sigh of relief and pray that never again, does the nation go through the stress it has gone through in the hands of Boko Haram in the last five years. With over 10,000 killed, according to the Sambo Dasuki, a retired colonel and national security adviser, Nigerians can the cup is now half-filled rather than being half-empty.

Without a ceasefire or peace deal, the blood would continue to flow.

Advertisement

Add a comment