BY OLADEINDE OLAWOYIN

As the aircraft roared through the runway of the Nnamdi Azikwe airport in Abuja, my mind raced through a mélange of issues. The air was foggy, and so were my thoughts. I was about to meet one of the marquee names in contemporary Nigerian journalism. Uncertainty collided with anxiety.

Before then, I had met him without meeting him. I met him on the pages of Dele Olojede’s 234NEXT newspaper, in stories that took the veil off the dark faces of corrupt politicians, in headlines that arrested the attention of cynics, in revelations that haunted those who pilfered our collective patrimony. I met him also on the websites of avant-garde platforms like Sahara Reporters, and on the lips of young journalists who spoke of him in awe. But until that morning, I hadn’t met him in the flesh.

As we drove out of the airport, and the car glided through Abuja’s well paved highways, thoughts about our impending meeting captured my mind. And so his looks, his character, his demeanors—they all occupied my imagination. Was he short and ‘brief’, like his sentences? Or was he rather gangly and ‘long’, like the length of his pieces? Did he exude an aura of dread, his luminous eyes fear-inducing, like the unifying theme of his many scoops? Uncertainty loomed.

Advertisement

Soon, the car snaked its way into the semi-quiet ambience of Mambolo, and I was ushered into his presence.

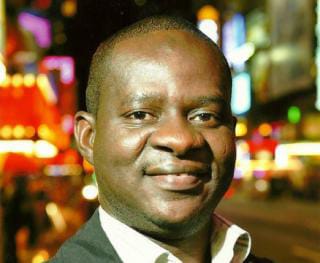

And there he was, Musikilu Mojeed, sitting in his office with benign mien, a smile adorning his face. He spoke softly, as though the words came out in slow motion. But his boyish demeanor came with a bonhomie that would help break down the wall of uncertainty between us. That moment, in the haze of the December harmattan, anxiety gave way for surprise, and, pronto, surprise graduated into camaraderie.

In the pantheon of Nigerian journalism, there are many gods. First were those who wrote their ways into the lore of Nigeria’s independence: Macaulay, Zik, Okoli, Enahoro etc.

Advertisement

Decades later, a generation rose from the shadows of repression and fought the military head-on, not with guns or daggers or Ogbunigwe, but with rare courage and dare-devil conviction. Enter Dapo Olorunyomi, Babafemi Ojudu, Bayo Onanuga, Owei Lakemfa, Richard Akinnola, Doyin Mahmoud etc.

About a decade before Olorunyomi et al were locked in mortal combat with Abacha and his disciples of death, Dele Giwa, the prose stylist, was letter-bombed into martyrdom in his home in Ikeja.

In the wake of Abacha’s reign of lunacy, some didn’t live to tell the story, like Bagauda Kaltho, who mysteriously disappeared into immortality. Some others still nurse the scars till today, like Kunle Ajibade, who was jailed on spurious charges.

The contemporary scene parades journalists and writers who illuminate our minds, shining the light in beautiful marriage of delectable prose and sound logic. Enter Abimbola Adunni Adelakun, Simon Kolawole, Reuben Abati, Lasisi Olagunju, Moses Ochonu, Sam Omatseye, Idowu Akinlotan, Bamidele Ademola-Olateju, Olakunle Abimbola, Olusegun Adeniyi, Adebayo Williams (Tatalo Alamu), Pius Adesanmi, Farooq Kperogi , Simbo Olorunfemi , Asaju Tunde e.t.c

Advertisement

That Musikilu Mojeed (MM) has earned a special place in the pantheon isn’t a matter of debate, having written some of the most consequential pieces of (journalistic) works to ever come out of Nigeria. He has equally trained a generation of journalists nurtured in the tradition of courageous elevation of truth, defense of freedom, and protection of the weak.

Heroes are not shaped in the same battles, or so argues Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces. As it is in literature, so it has been for me in journalism. And so Mojeed stands tall among those who showed the lights, but he isn’t alone.

Bayo Alimi lit the fire of my love for arts and literary criticism back in Igando High School on the cusp of the millenium, while Yinka Agoro and Rotimi Bolarinwa provided insights into newspapering in the belly of hills in Eruwa. Hajia S.S AbdulBaqi, Dr. Lambe Mustapha, and Professors Lukman Azeez and Mahfouz Adedimeji influenced my interest in the written word at the University of Ilorin. But if the iconic Alhaji Liad Tella told me how far I could travel on the wings of sentences, it was in Mojeed’s hand the idea blossomed. So among those who shaped my journalism journey, MM stands out in terms of impact and influence.

Outside of the classroom, he was the most consequential of teachers who believed in my gift as writer and columnist, leading me through dark alleys amidst thunderstorm and lightning. He gave me, first, the most important of platforms to soar.

Advertisement

I remember now how we met on Mark Zuckerberg’s game changer of a tech invention. I had written a few lines (I called them ‘doggerels’!), and posted them on the platform. He was impressed, and then he reached out to me. “You write beautifully,” he quipped, or some words to that effect. I replied to his messages and the story changed from there: two strangers became mentor and mentee.

Since then we have traveled to places and had encounters with people, experienced turbulent periods of feuds and enjoyed moments of festivities, rejoiced over shared victories and condoled with grieving colleagues, interviewed society bigwigs and had chats with the hoi polloi, argued over bowls of Amala in Agidingbi and walked past bouquets of flowers in Lekki.

Advertisement

He isn’t without his flaws, like all humans, yet Mojeed’s most fascinating quality as a model journalist isn’t his famed prowess in generating story ideas. It’s not even his rare facility for brewing juicy tales out of the most banal of documents. It’s definitely not his wide network of contacts. To my mind, MM’s most enduring trait is the special interest he develops in young people.

Like Peter Ustinov, the British actor who found immortality in children, MM has shown that the surest path to immortality lies in breeding the next generation of journalists.

Advertisement

Through him, I met not a few colleagues who would become friends and family. From Uncle Dapsy, I learnt how to breathe life into dead, wooden sentences, and from Idris Akinbajo, how to turn in copies and beat deadlines with the speed of light. From Ololade Bamidele, I learnt the discipline of editing, and from Ini Ekott, the beauty of frugality in word usage. Ben Ezeamalu showed the way in effortless transformation of phrases into pure magic, and Nicholas Ibekwe exemplifies the nobility of courage in the face of threats. From the trio of Bisi Abidoye, Bassey Udo and Festus Owete, I saw how the weight of experience could ease deadline tension, and Joshua Olufemi provided insights into how to make sense of esoteric data. That morning in the thick of the harmattan haze of December 2016, Oti and Fred Adetiba welcomed me into PT with a sort of hospitality that fascinates till today. From Mallam Abdulaziz, Alhaji Sani Tukur, Samuel Ogundipe, Damola Owoseye, Richard, Oyewobi, Ebuka, Kemi Busari, Abdulkareem, Adedigba Azeezat, QueenEsther, Ayodeji Adegboyega, Hassan Adebayo, Seyi Bangudu, Kabir Yusuf, Mojeed Alabi, Eludini, Jayne, Jide Alaka, Dayo Williams, and the entire PT team, I have learnt the beauty of teamwork and human relations.

Beyond issues of editorial concerns, and rather unknown to many, MM has an incredible sense of humour. Beneath the cold, impassive face of an editor dissecting far-reaching issues of illicit finance is a mouth replete with humorous lines.

Advertisement

There is the popular joke of an anecdote that satirizes the folly of the Nigerian public servant. “Even when he writes an ordinary leave letter, he’d still hide it from the public,” Mojeed once said, deadpan, his words depicting how the Nigerian abhors the simplest of issues around transparency and openness.

I also remember that afternoon in ex-president Olusegun Obasanjo’s rustic hometown, Ibogun-Olaogun. We were there together for an interview. But just before we brought out our tapes, a folksy OBJ swaggered to rhythmic beats of Bata from local raconteurs. MM walked gently beside him, and they exchanged some inaudible words. To my mind, it was as though he challenged OBJ to wriggle his waist in deference to the dance de jour, Zanku. Like a battle-ready general, OBJ leapt forward to display some funny moves. And so in Ibogun-Olaogun, the rhetoric collided with the gymnastic in awkward symphony. Humour met humour.

As he clocks 50, it will be apposite to compose 50 haiku for Mojeed, and if we stretch the imagination towards some punny mischief, the Japanese poems could even serve as what the Yoruba would refer to as…er…’Ogun Aiku’ (antidote for immortality). But in journalism, MM has earned immortality already. Still the noble Prophet of Islam encourages us to appreciate those who illuminate our paths. So here is wishing him the best of the remaining decades, and, to echo the immortal bard William Shakespeare, “with mirth and laughter let old wrinkles come”.

ADIO’S ARC

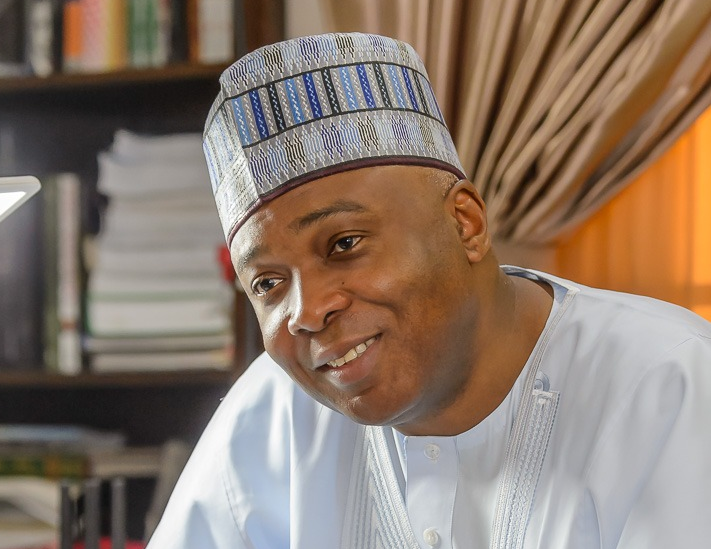

He moved away from the aisle gently, his voice calm and courteous. “Oh, sorry,” he quipped. He stood ahead of me, and I had requested to move through the aisle on my way to the podium. It was December 2018, and we were at the NECA House as recipients of the Wole Soyinka Awards. He,for his exemplary role in public service; and I, for my reportorial efforts.

That was my first encounter with Mr Waziri Adio . The second encounter was via text messages. He had just left his position at NEITI, and I needed to speak with the new head. He was busy, but he sent a message when I called. “Please send a text,” he wrote. I explained my mission and, pronto, he sent me the new head’s telephone number.

On both occasions, it’s doubtful if Mr Adio knew me from anywhere. But he was just being the man I had heard about — courteous and kind.

Last week in Abuja, he launched his book, The Arc of the Possible, published by TheCable Books. I haven’t read it but was quite impressed by the reviews. As an energy reporter, I could testify to some of the claims, particularly the incredible works he did with NEITI’s annual reports. We barely encourage those who make impact, however minimal, in public service and it’s at the base of our leadership recruitment misadventure over the years.

Dr. Okey Ikechukwu argued in his review that the book should be made a compulsory read in leadership schools. I can’t agree more. Congratulations!

Oladeinde, a deputy business editor with Premium Times, writes from Lagos.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment