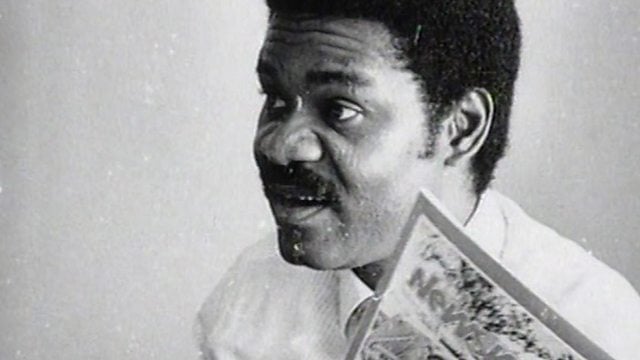

Dele Giwa

Since that dark Sunday morning on October 19, 1986 when renowned journalist, Dele Giwa, was parcel-bombed by a God-knows-who, Nigerian journalism, Nigeria and government-journalism relationship have not recovered from that nightmarish experience. And in diverse regards. First, because it was a novel manner of assassination, the killing of Giwa opened the floodgate for subsequent demystification of the oppression of journalists in Nigeria.

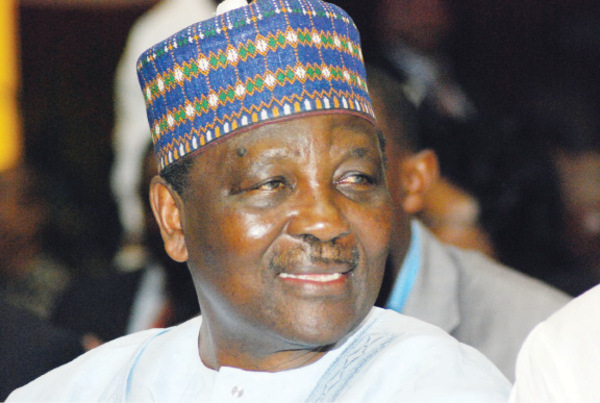

For the Ibrahim Babangida military government which was the first suspect in the killing, Giwa’s death demanded new methods of arresting critical journalists without slamming any chains around their feet. Babangida thereafter sent for Antonio Gramsci, Italian activists who taught world rulers on how to covertly manipulate and shape thoughts and ideas of the people, get critics to eat off rulers’ tables without the latter shedding a single pint of their blood.

Dele Giwa represented the finest brew of Nigerian journalism of the consequential post-Second Republic combat-of-the-military-class era. Born Sunmonu Oladele ‘Baines’ Giwa in 1947, he hailed from a very poor family of a father who was a hired hand in Oba Adesoji Aderemi, Ooni of Ife’s palace and rose to becoming a colossus of the written words. After earning a degree from Brooklyn College in 1975, Giwa worked for four years with The New York Times as a news assistant and thereafter came back home to work for the influential Daily Times. In 1984, he pulled his galaxy of media friends to establish the Newswatch magazine, a move that was said to equal Nnamdi Azikiwe’s unique and remarkable entry into newspaper press journalism in 1937 with his West African Pilot. It was colourful as well as embodying the critical ingredients of journalism at the time when military autocracy had dragged on for interminably long period and at a time when the verve for democratic renaissance was sweeping round the globe. It was thus not surprising that the hostile and investigate bents of the Newswatch, Giwa’s piercingly critical Parallax Snap column, as well as the unpardonably unsparing stings of his colleagues’ pens would lead to the fatal assassination that Giwa suffered in the hands of his traducers.

The thirty-third anniversary of Giwa’s assassination is however not a moment to engage in puerile revisionism, buck-passing on what was or was not responsible for his murder but an opportunity to critically look at current trends in journalism practice, the state of Giwa’s kind of journalism and the vanishing crop of Giwa-type journalists in the Nigeria of today. In other words, let us literally slice the flesh of this avant-garde journalism icon in a post-mortem, perhaps we could find what detains the practice of the profession for this long. More importantly, with Giwa’s gruesome murder, we should ask ourselves whether there has been a let in government/press hostile relationship and what is the fare of current civilian government in its interface with the press?

Advertisement

While not engaging in needless revisionism, it must be said that it is a colossal shame that, 33 years after Giwa’s murder, the Nigerian state has waffled in telling the world who actually murdered the journalist. Unresolved murders have unfolded into one another, its culmination being the murder of Nigeria’s Attorney General in 2001 without identified culprits till today.

Anyway, the Nigerian press has had a ding-dong history from the colonial period. With a remarkable pedigree as predating the Nigerian state, having been in existence since the establishment of the printing press in 1846, with the first printing press which was installed by the Presbyterian Church in Calabar and eight years after, precisely in 1854, the establishment by the Reverend Henry Townsend of the Church Missionary Society (CSM) who inaugurated a printing school in Abeokuta and four years later, founded the Iwe Irohin (Iwe Irohin fun awon ara Egba ati Yoruba), the Nigerian press is unarguably older than Nigeria which came into being in 1914, almost a decade after. The press acquitted itself very well in the fight against the sit-tight inclination of colonial overlords and fought colonial orthodoxy with a remarkable zeal and positioned the newspaper press on an enviable pedestal. It did this until it gradually became an important factor in colonial society and politics in West Africa. Galaxy of immortal stars of Nigerian press like Robert Campbell, a West Indian businessman who had settled in Lagos, through his publishing of the Anglo-African newspaper which he founded in 1863, down to a flurry of newspapers which came on the scene in subsequence, made the early press to constitute a formidable bulwark against colonialists. All in all, a total of fifty-one newspapers were established between Lagos Times newspaper of 1880 and 1937 when Azikiwe came on board with Pilot.

The First Republic became a downward slope for the newspaper press which had made such a promising landmark on the sand of time. Without any let, the Nigerian press mutated from the glory of the anti-colonial struggle into a battleground for power struggles among politicians. It was so bad that critical reviews of the press of the time hold the press of the time responsible for the collapse of that Republic.

Advertisement

After the collapse, the press went into its vanguard role again. From 1966 to 1979, the Nigerian newspaper press, which had now had a sprinkle of state-owned radio and television stations, held the military accountable to its promises. It was no coincidence that journalist Amachere had his head shaved by military administrator, Diette Spiff for standing up to the military top-brass. But immediately the military vacated the dais and politicians took over in 1979, the press morphed from being an avant-garde into a mouthpiece of political opportunism. Truth became multi-faceted, depending on which medium you held in your hands. The press only regained its composure when the military struck again in 1983, a battle it fought all through the Muhammadu Buhari/Babangida/Abacha years until the military returned into the barracks in 1999.

I have gone into this long history to show that the press has been oscillating from the noble, the selfish, the fissiparous, to the ambivalent since its establishment in 1854. A two-pronged estimation of the press of the Giwa era is available among analysts of the time. The Giwas emerged as the doyen of the crop that is pejoratively referred to as the Benz Editors. The “flotsam and jetsam” classification of the “press boys,” pioneered by Obafemi Awolowo, died with the advent of the Giwas in the 1980s. They were editors who held bachelor degrees from America, UK and Nigerian universities who could not settle for the fringe lifestyles of the journalists of the immediate past era. They drove Mercedez Benz cars, lived in big houses and could not be pushed around. Not only did they change the face of the newspaper press, they changed its tenor as well, bringing foreign inputs into the practice.

Journalism practice of the current Fourth Republic, from 1999 till now, is the lowest in content and form, since its advent. It has suffered serious bombshells from artillery fire of allied forces of economic downturn, gross incompetence of practitioners, manifest dissembling of the Nigeria that used to be an Eldorado in the eyes of forefather practitioners and other forces. The advent of the social media is the final nail on the coffin of a Nigerian press that was before now gasping for breath. As it is now, media practice is comatose, waiting for the pronouncement of its death by a fidgeting medic and its internment by the pallbearers.

The first major instigator of the death of the Nigerian media today is the absence of Nigeria or the death of Nigeria in the ears of Nigerians. Media practice in the immediate post-colony reckoned that there was one country called Nigeria that gummed her people together, to which the practitioners needed “to be faithful, loyal and honest.” Today, practitioners have found out that that was the greatest scam of the century and indeed, there was no country that needed anybody’s faithfulness or loyalty. Rather than Nigeria to whom the early press and its practitioners paid obeisance, the god of the personal belly is the most recent god to which practitioners give propitiations. When they see how governments after governments preach the gospel of ethnic ascendancy, how looting of treasuries has become abiding credo of governance, media practitioners suddenly become apostates of those lofty dreams.

Advertisement

Second is that there is a consistent worship of mediocrity in Nigeria which is also becoming an abiding pattern. You do not need to strive for excellence in a Nigeria where governments appoint the worst of us to superintend over the best of us. A president or governor or minister could appoint his sexual liaison as minister – sorry, I remove that – as commissioner or adviser and we will live happily ever thereafter. We live in a Nigeria where sex symbols in BBNaija are rewarded with multiple of millions while First Class graduates get mere applauses. There are no scholarships from government as incentives to the remarkable among us any longer and falsifications rule the universities now like a panjandrum. It is this set of falsifiers, who exchange moans on top of lecturers for certificates, who are the reporters who write the stories in the Nigerian press that we hypocritically expect to benchmark the resilience pens of the Amachrees and the lush journalism of the Peter Enahoros. In other words, when you pick a copy of a Nigerian newspaper or you hear a radio/TV broadcaster talk, no one needs to tell you that a holocaust is afoot in the Nigerian press.

The parlous economy has brought a survival-of-the-fittest and elimination of the weakest into journalism. Media houses are gasping for breath, sparsely pay salaries and cannot afford refresher courses for practitioners. Mediocrity is ruling the airwaves of the newsroom. Governments after governments and the corporate world, aware of this emasculation, are exploring this to their advantage. Rather than the brown envelope malady, what I call corporate corruption is the rule rather than the exception in the media. Since he who pays the piper calls the tune, advertisers and governments who control huge advert bucks easily decree negative news from the list of materials to communicate to the public.

Except with its sudden resurgence in the Buhari era, physical emasculation of journalists by clamping them in detention had paled remarkably. Nor do we witness the assassination of the Giwa type. Government/press relations are no longer marked by constructive engagements but cat and mouse relationship. Perhaps, a reflection of the inability to process the depth of media involvement in policy decisions, this government has not only succeeded in dulling the robust, though adversarial, interface of government and the press, it has remarkably demystified the press, making any onlooker to wonder if the lofty roles of the press of yore were not hyped.

The most fatal blow to media practice in Nigeria, and I dare say, the world, is the social media. Unbeknown to it, the rest of the world envied the press’ art of purveying information messages through its media outlets. Immediately the social media became activated, it became a fertile ground for all manner of persons to become press icons. Being an uncensored turf with licence for licit and illicit communication, the social media has become renowned for fake news, puerile murder of journalism rules and ultimately, the graveyard of the sacred and old journalism profession. It is so bad that traditional media is going extinct. That is the memory that Giwa’s death, 33 years after, spurns in the air.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment