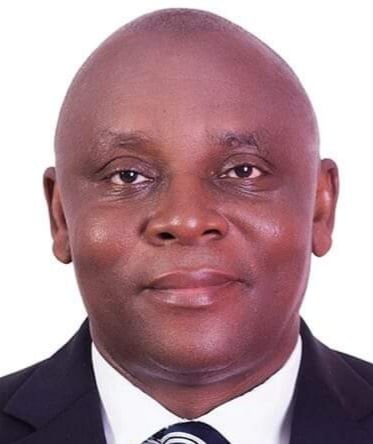

General Yakubu Gowon has never really been given to flamboyance, and so, when he turned 89 last week, the celebrations were typically modest and subdued. There were however warm greetings from across the land. Perhaps, next year’s would be a bigger and more ostentatious event; and I hope that is when he would publish his long-awaited memoir.

His autobiography is a story he owes this nation – a country he loves so dearly – and because he has been so closely involved in, and linked with important parts of Nigeria’s history, Gowon’s memoir will be largely Nigeria’s story. Gowon governed Nigeria from 1966 to 1975, the single longest span for any of our leaders.

Olusegun Obasanjo ruled cumulatively for 11 years, three as a military leader and eight as a democratically elected president. Obasanjo has written two accounts of his life: My Command (1980) and My Watch (2014). We however need Gowon’s book to complete the story of Nigeria, fill the gaps in other accounts and documents for the current generation of leaders and posterity his experiences and ideas on nation-building. At a time when the country seems to be suffering from severe leadership deficiency syndrome, Gowon’s autobiography would provide the single most invaluable guide and guidance.

I like to think of Gowon as our own Eisenhower. Both share some common similarities, not just because they were both born in the middle of October. Edward David Eisenhower (October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During the Second World War, he served as the supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe and achieved the five-star rank of as general. Eisenhower planned and supervised two of the most consequential military campaigns of the war: Operation Torch in North Africa and the D-Day invasion of Normandy in 1944.

Advertisement

Gowon led our country during a vicious 30-month civil war and succeeded in foiling its breakup. But it was his leadership after the war that brought out the humanity in him. By ensuring that the people of Eastern Nigeria did not suffer official discrimination and persecution due to their participation in the rebellion, Gowon endeared himself to me and millions of others as an authentic Nigerian hero despite whatever frailties he may have. We all do, anyway. After the war, Gowon launched a programme of three Rs (Reconstruction, Rehabilitation and Reintegration) as an act of compassion and healing to help in managing the trauma of the internecine conflict and set the country on the path of recovery and remediation. If only his successors had continued on that trajectory.

From Gowon’s memoir, we will learn more about the war; how he ran a war economy and the thinking behind the Three Rs. It was during his nine years as head of state that the country built many of the road and bridge infrastructures, universities, airports and power plants that we have today. Gowon was and continues to be obsessed with the ideals of Nigerian unity. He introduced Unity Schools (formerly known as Federal Government Colleges), student exchange programmes and the NYSC scheme to promote national harmony, and initiated the construction of several interstate roads to interconnect this vast land.

I am eager to read about the leadership challenges Gowon faced during and after the war. The failure of the Aburi Accord; roles of the super perm secs and the civil service in designing his economic blueprints, especially the national development plans; managing a war economy; the prosecution and imprisonment of Chief Obafemi Awolowo and his subsequent pardon and role in his government; the war-time diplomacy and international relations; state creation of 1967; his overthrow as he was attending OAU (now AU) summit in Kampala; his life and studies in the UK; the Dimka coup and his ‘’implication’’ in it; the 1973 census; the introduction of the Naira and all other eventful dramas and events that have been part of his long life. In 1973, the Yom Kippur war broke out in the Middle East and it led to an astronomical rise in crude oil prices. Nigeria witnessed its first oil boom which funded Gowon’s massive construction and reconstruction projects across the country.

Advertisement

Is it not a wonder that despite all that oil wealth, Gowon, his military governors and all the others who served in his government did not retire into stupendous wealth? Compared to the time of IBB and Abacha, and considering what the politicians have been doing with our resources, Gowon is a puritan, or an angel, if you like. I have never heard that he has acquired private jets, big mansions and assets.

In 1972, his government enacted the Nigerian Enterprises Promotion Decree (amended in 1977) which was meant to effect changes in the ownership structure of businesses in Nigeria and provide opportunity for indigenous capital to have assertive control of the economy. In other words, the law mandated foreign companies in the country to sell portions of their shares to Nigerians and further restricted foreigners from investing in certain sectors of the economy.

Most of the people who bought those shares were Yoruba. The Igbos were too badly impoverished by the war to invest and northerners were more interested in their farms to bother. The minorities did not even know what was happening. Many therefore believe that this law is responsible for the disproportionate dominance of Yoruba people in corporate Nigeria.

But amazingly, Gowon did not acquire any of those assets for himself. His uprightness throws some light on the absence of morality and probity in governance in today’s Nigeria. It is my conviction – and I have shared this with a few – that a decadent, corrupt and inept leadership as we have will never birth development, no matter how hard it tries. Development is a product of cumulative years of hard work, self-sacrifice, creative thinking and long-term planning. A political class that revels in election rigging; vote buying and forgeries is incapable of doing the heavy lift that drives development.

Advertisement

So many books have been written by Biafran generals and others who fought on the side of the seceding side, and I have read almost all of them. I saw the conflict as a toddler and I still remember the day my parents and siblings fled our home when rampaging soldiers invaded our village. Immediately, we became internally displaced persons in another village from 1968 to the end of the war in 1970. Homes were completely razed down. Gowon’s memoir will therefore provide a balance to the different accounts that have been published so far, and explain many developments in Nigerian history that we know nothing about.

Both Yakubu Gowon and Olusegun Obasanjo have had the most positive impacts and footprints on the geography and politics of this country. Gowon’s book will therefore fill a yawning space in our library, history, cultures and politics. I have neither met nor spoken to General Gowon. The closest I came to seeing him was last May when some writers and I jointly presented a book we wrote on Prof. Yemi Osinbajo. It was a virtual event and I was pleased to see the retired general pop up when it was time for him to make his remarks. He looked well and healthy. I wish him the very best in the remaining years of his life.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment