Supreme court

In March 2017, columnist, Eric Teniola, began his article tracing the history of appointments to the Nigerian Supreme Court with the following lines: “[c]risis is not new to the Supreme Court in Nigeria. From inception, there has always been one crisis or the other in that court”.

That crisis of appointment has often been accompanied by a crisis of retention and mortality. When Stafford Foster Sutton retired as the last foreign Chief Justice of Nigeria (CJN), the government appointed an Egba prince, Adetokunbo Ademola, to succeed him on April 1, 1958. 14 months later, Olumuyiwa Jibowu, the first Nigerian on the then Federal Supreme Court, whose supercession by Ademola into the office of the CJN was facilitated by a suspiciously well-timed complaint about partisanship (which supposedly made him unfit for the office) died suddenly at 59. Since then, the supreme court has lived with triple crises of attrition, retention, and appointments.

20 years ago, Nigeria’s supreme court was in a very bad way. On October 3, 2002, Vanguard newspaper in Lagos led with the caption ‘Severe ailments ravage three Supreme Court Justices’. One of the justices named in the story was Okay Godfrey Achike, whose judicial trajectory followed the academic route.

Obi Nwabueze, distinguished law professor and currently Nigeria’s senior-most senior advocate of Nigeria (SAN), no less, described Achike as “a first-rate academic and a fine teacher”. A distinguished academic career had taken Okay Achike through the faculties of law at the University of Nigeria, the Ahmadu Bello University, and Nnamdi Azikiwe University as well as the Universities of Benin, Jos, and Lagos. In May 1986, Okay Achike became a judge of the high court of Anambra state. 15 months later, in September 1987, Achike joined the Court of Appeal Bench. In November 1998, Okay Achike became the 54th appointment to the supreme court bench. He was just under 66 years old and due to retire on December 23, 2002.

However, early in 2002, Justice Achike suffered a stroke forcing him ultimately to take early retirement from the Supreme Court at the age of 69 in August of the same year. He was too ill to even attend his own valedictory session the following month. One year later, in August 2003, he died.

Advertisement

The early retirement of Justice Okay Achike happened at the beginning of a bad season for Nigeria’s Supreme Court. Over the next three years, seven Justices left the Supreme Court. These were Justices Emmanuel Ayoola, Dennis Edozie, Anthony Iguh, Ekundayo Ogundare, Obioma Ogwuegbu, Chukwudinka Pats-Acholonu, and Samson Uwaifo.

Of these, Ekundayo Ogundare died in London in December 2003 from causes associated with colon cancer while Chukwudinka Pats-Acholonu died suddenly on May 14, 2006, of a suspected cardio-vascular incident. Two others – Anthony Iguh and Obioma Ogwuegbu – survived hospitalisation for critical illness shortly before retirement. Indeed, Justice Ogwuegbu described his own survival as “a medical miracle”.

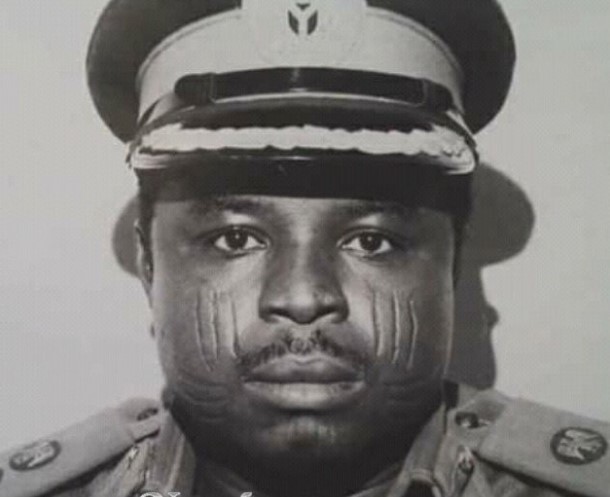

In comparison to the three serving Justices who died or were incapacitated over three years between 2003 and 2006, the Supreme Court suffered the death of three of its serving Justices over the 25 years from 1977 to 2002: Onuorah Dan Ibekwe in 1978 at the age of 58; Chukwunweike Idigbe in 1983 at the age of 59; and Augustine Nnamani at 67 in 1990. No Justice of the Supreme Court died in service in the 12 years to 2002 since the untimely passing of Augustine Nnamani.

Before the untimely death of Dan Ibekwe in 1977, the death of a serving supreme court justice was almost unheard of. When he died on June 1, 1959, Olumuyiwa Jibowu was a justice of the then federal supreme court, which was the equivalent of today’s court of appeal. The apex court for the country then was the judicial committee of the Privy Council in London. John Idowu Conrad Taylor who died at 56 as the chief judge of Lagos in 1973, had served for three years as justice of the supreme court from 1964 until he accepted the appointment as the chief judge of Lagos state in 1967. Similarly, Buba Ardo, who died at 60 in 1991 as chief judge of Gongola state had stepped down from the supreme court into that role.

Advertisement

Two weeks after the death of Justice Pats-Acholonu, on May 30, 2006, this writer complained in an article about “the stresses our judges go through”, which argued that “mortality figures of the supreme court also tell a story about the working conditions of the supreme court”. Even worse, they tell a story about how those working conditions have evolved over time in the wrong direction. This matter of increasing attrition and mortality of justices is also a reflection of the management of work streams, occupational health, and well-being in the supreme court and, therefore, of a deterioration in deliberative assets that go into the court’s decision-making.

16 years after that complaint in 2006 about the stresses that Nigerian judges have to endure, memories appear to have faded and the recent complaint by the current Chief Justice of Nigeria (CJN), Olukayode Ariwoola, about the triple crises of attrition, retention, and replacement at the Supreme Court appears to have inspired a reflex of handwringing, attended by a flurry of consciousness most of which look both undigested and hardly helpful.

It all began with the valedictory session on September 15, 2022, for Abdu Aboki, the most recent justice to retire from the supreme court, where the CJN complained that his exit had “drastically depleted” the ranks of the bench of the court from the constitutional ceiling of 21 to 13. When they began the year, the CJN lamented, they were 17.

From the Body of Senior Advocates of Nigeria (BOSAN) the reaction was swift and immediate. On behalf of the Body, Onomigbo Okpoko (SAN) claimed that the complaint of the CJN was self-inflicted because of an appointment process that “appears to have been designed and operated to exclude good and competent lawyers from being appointed Justices of appellate courts”. Two years before this, the Independent Corrupt Practices Commission (ICPC) had reported that some senior lawyers were knee-deep in corrupting the judiciary with unmentionable sums. BOSAN did not seriously appear to have noticed this report.

The implicit suggestion by the BOSAN is that there is a sudden or quick fix to these crises in the supreme court which are nearly 65 years at least in the making. The idea that the country can appoint or replace its way out of these crises is unviable because such an approach does not respond in any way to the underlying pathologies that afflict the court. The issues are much more complex than that.

Advertisement

Three reasons make this a good and necessary time to undertake a careful diagnosis of what afflicts the court. First, the legal profession, the public, and the politicians very much agree that the supreme court is living through a crisis but few have bothered to lay out clearly what the nature of the crisis is or how it came about in order for consensus to emerge as to how to fix it.

Second, all major issues in democratic and electoral politics in Nigeria sooner or later become the subject of litigation or judicial decision-making. The Economist in 2008 famously described Nigeria as a democracy by court order. In the pecking order of the courts, the supreme court dictates what happens. Any crisis afflicting the supreme court in this system sooner or later occasions system-wide contagion.

Third, the country is in an election season which will be followed by a transition to a different government in another seven months. A competent diagnosis at this time should enable the country to provide fixes ahead of the election dispute resolution season or prepare to provide them immediately after the transition. These rationales dictate, therefore, that we take a first principled look at the issues that afflict Nigeria’s supreme court. That is the only way to find out what can be done to address them.

A lawyer and a teacher, Odinkalu can be reached at [email protected]

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment