BY CHUKKY IBE

There are a few things strong enough to rip fan-yogo out of my hand. Death is on the top of that list. Before I could look left again, I felt the hot metal press against my already neat 7 year old skin. The impact flung my spider-man bag off my back and onto the top of the street. The cry of a fully grown boy drowned out the roar of the engine. Half the skin on my left lag had melted away. What felt like the force of a thousand canes flogged up my spine, and rested on the back of my neck.Helplessly I watched as the fan-yogo leapt out of my hand, and slowly melted unto the asphalt. No one is safe in Lagos. Not even a sinless boy, with fan-yogo in his hand, crossing the street on his way back from school. Crossing the street in Lagos will kill you.

The second time was around the corner from where my Spider-man bag rested, on-top of street from my school. Opposite the Eziamaka’s house.My cousins and I spent the weekend at a private pool with a family friend. I didn’t know how to swim and I was too scared to take of my shirt, so I decided to balance the pool-to-ball ratio between the kids section and the adults’ pool. I remember falling. I remember the bubbles escaping my throat, found away to float, why couldn’t I? I clung on to the water around me trying to make a ladder out of it. I felt the floor crash against my back. I closed my eyes, and breathed what should have been my last breath. And when I was awake, on the brick read floor, family huddled around me. The lifeguards who were payed to keep us safe were nowhere to be found.Only friends, and family, doing the best they could. The water escaped my mouth, I breathed in life. Swimming in Nigeria will kill you.

All these near death experiences – are very aje butter (botty). I know.

Advertisement

The DSTV had begun to scramble. But this night there was no rain, no rushing winds or anything of this vein. NEPA took the light back. We brazed ourselves for the concert; but no generator (gen) on the street bantered. Not even our obnoxious neighbour’s gen who sang all day made a squeak.

Slowly, we felt the cracks in the door as the devil opened up the floodgates. Our home began to shake. The windows crashed in perfect unison, the mosquito net stood on guard. We huddled like sheep in a lightning storm. It sounded like a thunder, but it felt like death. My mother sprung into action, Chinazom, Adaure and I were ordered to pack a light bag, stand in a line. My mother ran to the kitchen to turn off the gas connected to the stove. She unplugged all the sockets to the wall. She moved like she had been rehearsing for this all her life. She ushered us through the back door, to the gate that connected us to Aunty Ebere’s house. She said it would be safer there. We opened the connector gate ready to escape. So did she. Aunty Ebere and her 2 children with packed bags, standing in a line stared right back at us. She thought it would be safer in our home.We were too scared to laugh,too confused to cry.

The bombardment continued all night.We fell asleep in each other’s arms to a concert of bombs and faint distant cries. We waited for whatever it was that was going to come.Judgment was upon us like God did Sodom and Gomorrah. For my sins I am born in Lagos.

Advertisement

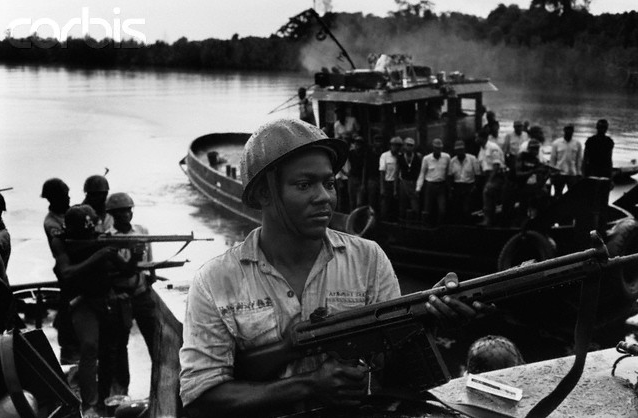

From what my seven year old mind could make outfrom the radio we had recovered from my mothers workshop, an accident had happened at the Ikeja military cantonment. Poorly stored ammunition caused a series of explosions that felt like a civil war. Without warning or prophesy the skies were lit with death. Our rented bungalow quacked with regret, the street opened up and swallowed innocence. The windows were broken, the houses were broken, our hearts were broken. The night was thick as death. Families attempting to cross the street drowned in a canal. They too clung on the the water in their fist and tried to make a ladder out of it. Many of the dead were children separated from their families and then crushed in the stampede of sorrows. The lifeguards who were payed to keep them safe were nowhere to be found. Only friends, and family, doing the best they could.

Anthony the fasted boy in our class, and his family lived in the barracks. He would eventually share his tales of survival and bravery. About how he ran through the explosions, collapsing buildings, exploding munitions, he dodged discharged bullets, shells and grenades and made it safely away from the destruction. I believe Anthony. He was the fastest boy in class. Eventually her an out of time and stopped coming to school. His family made it out because of his speed and bravery, but his home was now indistinguishable from fine sand. Many families in Ikeja still have not recovered from the destruction. Mothers are still searching for their hearts. Fathers still are searching for answers.

The military and the politicians said there was a mistake which led to an accident, which led to the death of thousands of people. Similar to the mistake made when the petrol tanker ignited in the middle of the streets. Similar to the mistakes made when the plane was cleared to fly and it crashed landed on the runways of our broken hearts. Similar to the mistake mads when schools are cleared for use, and they collapse into the laughter of bustling children. We make a lot of mistakes In Lagos.We do not make the mistake of naming our tragedies. No black Mondays, or dark Tuesdays, or 9/11s. We just call them by their real names. Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday. We have lost count of all the bodies and all the days. We stopped commemorating the anniversaries of disasters in Lagos. Every day in Lagos is someone’s disaster.

Every day someone loses their life to a senseless avoidable tragedy; to the mistake of their neighbour, or the negligence of a worker, or the incompetence of public officials. We have become so accustomed to senseless tragedy and avoidable loss of life in Lagos. We have made our beds in our graves not knowing when, or where or how death will come but fully confident it will. If not to us, then to someone we love. Death can meet you anywhere at anytime. But in Lagos, it comes more often, and it stays longer.

Advertisement

In Lagos we our discouraged from complaining and encouraged to fix the problems we find.“If you are not part of the solution, you are part of the problem.”“We are the leaders of tomorrow” we say. “Run for office, change the system.” But what do you do, when even the air on your street conspires against you. Should we not love our lives with the same veracity as we love our city and our country? And when we must, which should we choose?

A country has the responsibility to protect and secure the lives of her citizens. And it is only through this basic security that the nation derives legitimacy, its monopoly on violence and the moral authority to govern. If a country cannot by default, protect the lives of its citizens what do the citizens owe the country? You can breathe clean air in Kigali, you can drive safely in Kumasi. Why should we not to want to live in a place that promises you good air, clean water, and a commute that does not end in senseless tragedy. There is no shame in self-preservation. Some of Our country folk now believe risking death crossing an ocean is more secure than risking life in Lagos. This is not the easy way out. There is no shame in self-preservation.

To those who are development advocates and encourage people to return home, and encourage Nigerians to stay home, can you guarantee they will not be blown up by the tanker in front of their bumper. We know that development takes time and effort, but what about crossing the street, or going swimming, or sleeping? Not even money can buy you safety or security. A friend of the family once showed off his N200m bullet proof Mercedes, in the same breath he lamented the loss of his child due to sickle cell complications. For the wealthiest, all that needs happen is a decline in health to feel exposed to the elements of Lagos. The materially poor are constantly exposed to this.

To all those who complain about brain drain, and the need for citizenship retention for development, some of us just want to drink fan-yogo in peace. Not everyone is a civil rights leader. Civilians should not be asked to die for their country. When a flight filled with professionals and families takes off and crashes, is this not to a kind of brain drain, is this not the worst kind of brain drain?

Advertisement

I understand those who will feel strongly against this piece. Indeed I too am a patriot and I am not advocating against your advocacy. I am simply mourning the dead, and ask you give them their due regard. I am treasuring the childish desire to cross the street with fan-yogo in hand, enjoying a day at the pool, and the deep desire to go to bed without fear that your country will kill you in your sleep.

Ibe tweets @DrCibe. He also runs: https://ibezimako.com/

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment