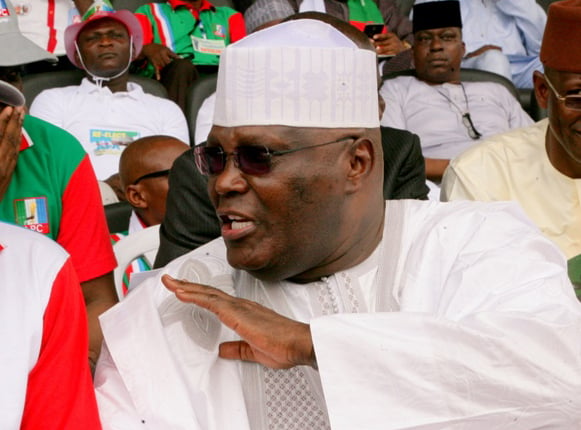

Most people would not dispute a high mark for former Vice President Atiku Abubakar as a public speaker. Or the quality of his interventions on national issues, like his speech at the public presentation of We are all Biafrans, a book by the Nigerian journalist and activist Chido Onumah, held at the Yar’Adua Centre, Abuja, on May 31, 2016.

He is “atikulate,” if I may assume the lexical license to use his name to modify a familiar word. He also has a firm grasp of issues that engage his interest.

In fact, unlike him, most Nigerian leaders at his level and above, with the exception of those in the First Republic, have tended to be inarticulate and to have a weak grasp of issues and an even weaker capacity to analyse them knowledgeably and with insight.

The country can be said to suffer from kwashiorkor of the intellect, with the dismal performance of most of its leaders in the cerebral department providing the basis for an accurate diagnosis.

Advertisement

But if Atiku had not always proven to be an exception to this sorry norm, he did so in the said speech widely publicised in the subsequent day’s newspaper lead stories as a call for the restructuring of Nigeria.

Nor did he disappoint when he spoke extempore at the event, fielding questions from the compere on sundry issues related to and beyond those he addressed in his prepared speech. The same clear-sighted view of issues and cogent articulation of his positions were evident as in the formal speech.

Some of the issues he addressed outside his speech were in relation to the Nigerian power sector and its seemingly irremediable underperformance. And though this aspect of his remarks did not generate as much interest from the media as his call for the restructuring of Nigeria, I consider it equally important and deserving of such critical attention as I intend to pay it hereunder.

Advertisement

His remarks on our power sector arose from his story of how he visited the Philippines as Vice President and realised that the Filipinos had problems of low power generation like us. According to him, they solved this problem by resorting to captive power, and in a few years generated enough power that they insisted on their then president continuing in office at the next election.

He then noted that on his return he recommended that we adopt captive power like the Filipinos as the means of solving our power problems. He affirmed that if we did we would have had the issue of inadequate power generation behind us in a few years, like the Filipinos.

He went on to criticise our choice of gas as the means of powering the NIPP stations we built instead of cultivating captive power as he recommended. He justified this criticism with the menace of vandals and the general instability in the Niger Delta, the main source of gas for our power stations. He then expressed strong reservations that we will “get it right” in the power sector until we resolve the problems in the Niger Delta.

And since the prospects of resolving those problems are not in sight, it would seem safe to conclude, from his analysis, that, unless we resort to captive power as he recommended, we may not soon see the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel or shall, thanks to the problems in the Niger Delta, continue to drill a tunnel for ourselves away from the promise of light.

Advertisement

His was, for me, a sombre, though-provoking, almost depressing summation. But I do not entirely agree with him.

First, I must admit that, as he suggested, it would be near impossible to expect to generate steady, let alone sufficient, power in our country from gas so long as the current unrest – the sabotage and other symptoms of socio-political anomie – persists in the Niger Delta.

But it does not follow that our choice of gas was wrong. Gas, being a plentiful resource in our country, was a low-hanging fruit, to paraphrase the former Minister of Power Prof. Bart Nnaji. And since it had worked for us in facilities like Sapele and Ughelli power stations in the pre-Niger Delta crisis era, it was sensible to resort to it as an energy source in the further development of our power sector.

So the choice of gas was not the problem but our inability to manage other factors that have made gas unable to work for us as effectively as it should.

Advertisement

“A captive power plant is a facility that is dedicated to providing a localised source of power to an energy user. These are typically industrial facilities or large offices. The plants may operate in grid parallel mode with the ability to export surplus power to the local electricity distribution network.” (Source:https://www.clarke-energy.com/captive-power-plants/).

So captive power is distinguished by its having a dedicated cluster of consumers; and an energy source would still be required to generate it. The energy source can be gas, as in the case of the Geometric Power plant near Aba. It can be hydro, as in the case of the NESCO facility in Jos. Both are captive power plants. It can be wind, solar or biomass depending on availability.

Advertisement

And if we could allow gas to be sabotaged for on-grid power, and allow those who sabotage it to succeed in holding our country to ransom and profit by doing so, what is the guarantee that the same gas or other energy source or the associated power infrastructure cannot similarly be sabotaged in the case of captive power?

Unlike us, Filipinos did not have a dedicated army of unpatriotic citizens – vandals and saboteurs waging war against their nation to ensure that the power sector remains dysfunctional. They did not have a country in which some citizens would egg on such saboteurs to satisfy their urge to see a serving government portrayed as ineffective and its political fortunes nosedive at the polls.

Advertisement

So we cannot expect what worked for the Filipinos to work for us without considering the differences in our respective local conditions. And it is those local conditions – a slew of abnormalities generally referred to as the Nigerian factor, and not unconnected to bad politics – that have prevented a remarkable captive power initiative like the Geometric Power plant from becoming operational years after its due date.

So captive power is not necessarily the solution to our power problems but can alleviate them if properly managed and freed from such factors that have hamstrung our generating power through gas.

Advertisement

Besides, our country has invested so much in gas-powered plants that it would be a huge waste to abandon it for captive power, which should at best complement options of grid power.

Our best option is to win over the forces preventing us from realising our full potential for generating power through gas, be they in the Niger Delta or elsewhere.

Email: [email protected]