Landmark Beach

Most of the tourists are Nigerians. Others are foreigners on work-related trips from faraway India, China, Pakistan, the US, and other countries.

On April 27, the kite surfers rode the tailwinds along Landmark’s beachfront in Victoria Island, Lagos state, too carefreely for a leisure destination that would soon give way to the initial stretch of a 753-km coastal road project.

A team of ready-to-dive lifeguards stood alert in front of the shoreline, spreading out by at least 40 metres apart to enforce safety. At 6pm, swimmers and surfers were summoned out of the water. One of the lifeguards pensively overlooked the orange hue of an imminent sunset.

“Everything you see here will be gone,” he remarked a little too loudly, struggling to be audible over the whistling beach breeze.

Advertisement

He shooed away a toddler straddling a long halyard, a little too close to the water, past the swimming time. The lifeguard shook his head in disapproval and passively added, “Thousands of people are employed here. Do you know how many businesses and jobs will be affected?”

Inflatable waterparks stood floating for patronage about 20 feet past the waterfront while sun loungers in their bikinis, beach hats, and shorts basked in nature and nap in a two-sided procession of tents.

Scattered all over the beach were chattering revellers — Asians playing soccer, half-clad tourists competing in a game of volleyball, restaurants serving fast food, vendors grilling meat, corporates raising a toast in picnics, paintball fanatics, and swimmers in the backdrop splashing pool water as music drowned out all else. Run by lifestyle businesses, these services see massive patronage.

Advertisement

Skis darted across the low-pressure water, picking up paying riders from ramps on both ends of the 770-metre stretch of beachfront. But as the fun continued, giant dredging vessels sand-filled away in a state-sanctioned operation that made the water brown with froth.

Landmark prided itself on owning the “first in-city private beachfront” in Lagos. It hosted a myriad of infrastructure and leisure activities offered by over 40 businesses, reportedly valued at over ₦20 billion. The infrastructure was said to have cost at least ₦25 billion to put in place. Paul Onwuanibe, its managing director, said the Landmark ecosystem accounted for over 12,000 direct or indirect employments and attracted over 3.5 million tourists annually in a venture that generated millions in weekly revenue since it started operating out of Oniru Estate in 2007.

On April 26, the Federal Ministry of Works convened a meeting to inform these business owners of the timeline for a demolition that would affect some of their structures along the beach. They were told to clear the first three kilometres of the right of way for the high-profile Lagos-Calabar coastal road project. The meeting discussed compensation for the affected business owners, whose structures were to be removed as soon as the next day.

By April 30, the lively musical feel of the beaches gave way to an eerie silence as bulldozers cleared out the remains of hurriedly uninstalled structures. Distraught stall owners moped from the sidelines at the ruins of what was once their thriving businesses.

Advertisement

The demolition started at Oniru Beach and extended to Landmark, The Good Beach, and Sol Beach, all within a 1.4-kilometre stretch.

MORE BUSINESSES SHUT DOWN

Most structures affected along the Landmark front are stalls or shelters made of wood, metal, and imported materials. But the beach had at least three brick buildings, including the restaurant Island Breeze and the Lagos Beach Club, both of which were demolished. Landmark, which holds a stake in these ventures, deactivated its app and initiated reimbursement for clients with funds in its system.

Olukorede Kesha, the Lagos controller of works, told affected businesses at the convened meeting that immovable structures of metal or brick deemed eligible for compensation will be sized up by height and width before being paid accordingly from a ₦2.7 billion fund.

Advertisement

“We will categorise those entitled to compensation and those to be paid on compassionate grounds,” she told the entrepreneurs, who shuddered at the thought of shuttering their businesses in a hurried demolition. “There are places Lagos had demolished that are yet to get paid, but that is not the case here. This government wants to work within the three years of the president’s term.”

The federal government has jurisdiction over navigable water bodies and makes it illegal to construct within 100 meters of a riverbank or 250 meters of any shoreline. Still, this regulation was not resolutely implemented along the Victoria Island beachfront over the years.

Advertisement

It meant that, while some occupants filed taxes, they had no valid claim to use those spaces beyond largely undocumented approvals.

The entrepreneurs were made to value their structures on the spot. Some hurried back to the beach to fetch supporting documents. Others made panicky calls to their managers, while others questioned the idea of valuing businesses by metrics that neglected the intangible losses incurred in advance contracts and irreversible financial obligations like bills or bank loans.

Advertisement

Some affected businesses had just begun operations in 2024, with projections set for one to three years to recoup their investment.

Breeze Beach Club in Landmark opened in December 2023 after three years of construction and infrastructure installation. The luxury relaxation spot patronised by foreigners and Nigerians alike set its yearly membership fee at $4,500 per head.

Advertisement

Akin Olaoye, an entrepreneur whose business was also affected, disclosed that the club cost over ₦500 million to build. He said its owner, who is now forced to refund subscribers, is being offered ₦100 million as compensation.

Onwuanibe had stated that the ministry did not consult with Landmark on the alignment for the coastal highway project and its environmental impact assessment. Landmark’s real estate is largely unaffected. This includes the Landmark Towers, the Landmark Boulevard, the Landmark Event Centre, and the Landmark Hotel. But the business loses its primary attraction without the beach.

JOB LOSSES UNDERWAY

TheCable contacted the affected businesses, but most declined to talk to the press for fear of a faceoff with government forces.

Emmanuel Abah manages Hangout Lagos, a lounge-bar business with over 30 staff members on its payroll and several suppliers in a post-paid contract. The prospect of being without employment scares the father of two, who fends for his aged mother and other dependents.

The manager told TheCable that Hangout is among the vendors categorised as “shanty” and deemed unqualified for compensation.

“Foreigners looking to fly into Nigeria often call us in advance to book our services. But when news of the imminent demolition spread, we started losing customers because most of our patrons assumed that we had already been shut down,” Abah said.

Abah said Hangout’s physical building alone cost ₦25 million to erect back in 2019, apart from its financial obligation to its workforce.

“I’m so sad and confused. I’m a family man. I don’t know what to do. We built Hangout with Landmark in mind. With the demolition now, we will be left hanging and indebted because we don’t have an alternative location for the business,” the manager added.

Abah said attempts at compensation should consider creating a relief package for the jobs lost to the coastal highway project.

“When state officials came, they called us shanties. So, we will lose everything. It’s not supposed to be that way, but we can’t fight the federal government,” the manager said. “If they listen to us, it’s fine. If they don’t, we will seek out alternative income sources.”

Bolaji Abubakar, who was visibly disturbed and agitated when he met with TheCable, is an entrepreneur losing on two fronts. He runs Mamichula, a three-location recreation spot, two of which are caught along the first eight kilometres of the road project’s right of way — his Mamichula Lifestyle opened on Oniru Private Beach in January 2024. There are also the Ciello Rooftop Club and the Honey Club. The branch at Oniru Beach within 1.4km of the right of way has been demolished; another awaits demolition at Ilasan in Elegushi within 7.9km.

Bolaji, whose properties were affirmed by the minister of works as being among those with valid right of occupancy, faces the tough decision of having to lay off over 300 employees and taking his business elsewhere if he must continue in tourism.

“Federal rates were adopted without concern for our gross. The property is measured, matched against how old it is, and run on standard rates. In 99.9 percent of cases, your structure is worth far more than that. But there’s very little we can do about our losses,” he said.

“I had projections for 2024 ending and another for when we hit five years. Now, I have been cut short. We’re back to square zero.”

Even businesses not caught in the beachfront demolitions recorded a drastic shortfall in patronage without the location’s primary attraction.

Ezekiel Tanimola oversees HR at the restaurant Amazon Spur, which was not removed. He said the business will likely drop most of its staff due to low sales. The pizza outlet, he said, used to make up to ₦1 million on any business day but now struggles to hit ₦50,000. The same obtains with Happy Spirit where a married Ogechi Arowolo runs the beachside grilling spot to support her partner’s earnings. Her sales dropped from ₦1 million per weekend to ₦20,000, which she says does not cover the cost of keeping the lights on.

ECONOMIC POSITIVES AMID LOSSES

A 753-km coastal highway connecting nine states holds great economic prospects for communities along its route, from improving transport infrastructure to boosting trade along the coast. The project could stimulate the Lagos-like economic profile further down south.

The Lagos-Calabar coastal highway is designed to connect Lagos to Cross River, passing through the coastal states of Ogun, Ondo, Delta, Bayelsa, Rivers, and Akwa Ibom, before terminating in Cross River. David Umahi, the minister of work, while unveiling a redesign, said two spurs will lead to northern states. One of those spurs is a 1,000km Sokoto-Badagry project still under design. The other is a trans-Saharan trade route of up to 461km passing through Enugu, Abakaliki, Ogoja, and Cameroon.

The Lagos construction firm Hitech was contracted for the Lagos-Calabar highway at ₦15 trillion or ₦4 billion per km.

The pilot phase of the construction, for which ₦1.06 trillion has already been released, started at the Eko Atlantic City and will terminate at Lekki Deep Seaport. It is a highway of 10 lanes that government sources said would be the first of its kind in Africa.

Chibuike Njoku, a tourist who frequents the beach with his family, argued that the highway project would aid interstate and regional commerce, opening trade to the south-south subregion where goods imported into Lagos in the south-west can be redistributed.

“It will allow the industries springing up in Ibeju-Lekki to access more distribution to the south-east and south-south,” he said.

“But the decision to construct it on the beach is rightly going to attract mixed feelings because it is one of the major tourist attractions in Lagos. This is the government sacrificing tourism for business priorities which unfortunately impacts people and jobs.”

Paul Onwuanibe had argued that the original right of way designated for the Lagos-Calabar coastal highway passes through a 1.5km stretch on the Water Corporation Road median.

But Umahi dismissed calls to revert to this alignment and stated that the area became developed with high-rise buildings and other costly infrastructure, necessitating a redesign to rework the initial plan and reroute the coastal road.

What was initially expected was for the coastal road to veer left of the Landmark beach and join back to Water Corporation drive. But while detailing the changes on the alignment, Umahi said the road is going to be split in two, where the route going towards Calabar will be on one side and another coming towards Lagos will be on the other. He said this prevents significant real estate disruptions.

Njoku said the disruptive nature of the project is a potential disincentive for investors looking to put resources into real estate close to coastal Lagos or similar ventures elsewhere around the country.

“Nigeria is seen as a country with a high rate of policy summersault. The government can give you all the privileges you need to run a business, only for another administration to overturn it,” he added.

‘NO PRE-APPROVED ESIA REPORT’

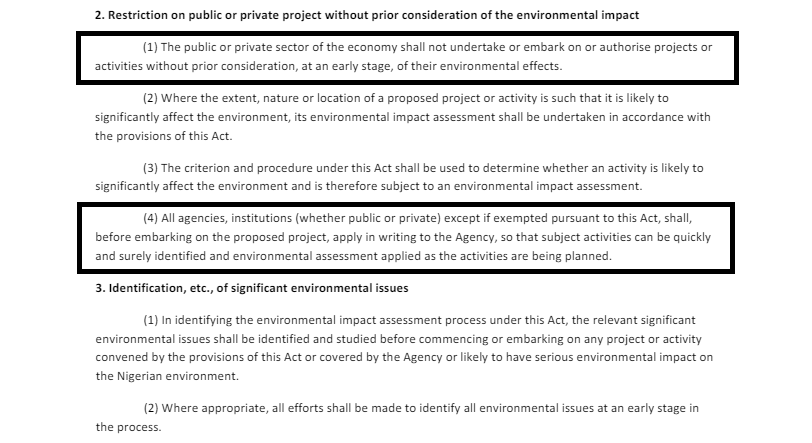

A major controversy around the Lagos-Calabar coastal highway is whether there was a pre-approved Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) report before a project of such scale commenced.

The EIA Act of 1992 states that an environmental impact assessment must be conducted, a report submitted to the Federal Ministry of Environment, and the report approved before any disruptive private or public sector project can commence.

The EIA process first involves scoping, which identifies key environmental issues to be encountered in the said project. The next step is conducting baseline studies to assess the current environmental conditions in the project area. This includes gathering data on air quality, water quality, biodiversity, soil conditions, socio-economic factors, and other relevant aspects.

Once baseline data is collected, impact assessment studies are conducted to predict the potential effects of the proposed project on the environment. These studies evaluate both direct and indirect impacts, as well as cumulative effects over time.

Next, mitigation measures are developed to minimise or offset any adverse environmental impacts identified.

The EIA process ends with preparing an environmental impact assessment report, which documents the findings of the scoping, baseline studies, impact assessment, and proposed mitigation measures. This report is submitted for review and approval before the project can begin.

Olumide Onafeso, a climate change modelling and environmental impact assessment expert, said projects not being undertaken solely in “green zones” (areas with no significant human activity) must have a report with an additional social impact component which is to identify potential social disruptions to be caused by the project and the decisions made to mitigate these disruptions.

Umahi, during a stakeholders meeting, failed to unequivocally affirm the existence of an approved EIA/ESIA when asked.

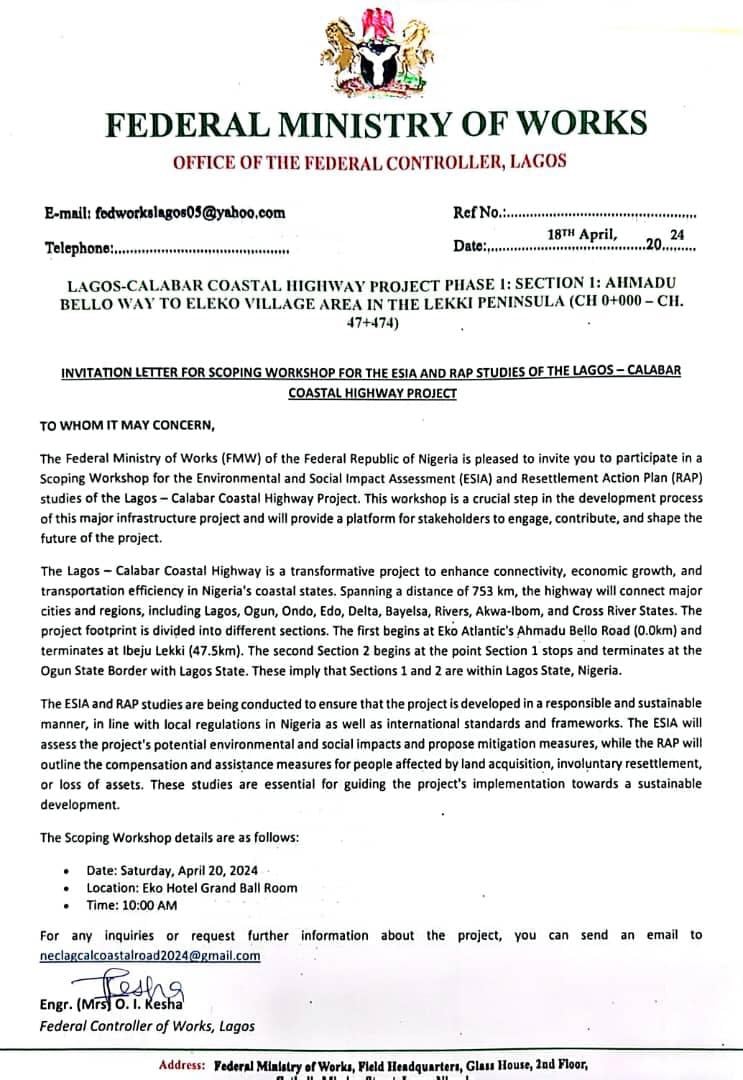

A letter from the ministry of works dated April 18 had asked residents living in the Section 1 and 11 areas of the highway in Lagos to attend a workshop for a scoping study after the project implementation had already commenced. It stated that this data collection was to ensure that the project is developed “responsibly and sustainably” and in line with local regulations and international standards.

This suggested that an ESIA, meant to be done in a project’s planning stages, was non-existent when implementation commenced.

“If impact assessment was done before the project design and planning, there could have been an alternative that doesn’t involve eliminating that beachfront,” Frank Nzeh, a Lagos-based civil engineer, said.

“I don’t see an issue with having that road just run close to the shoreline of those leisure areas. The third mainland bridge has all its pires and columns immersed in water. But piling in the highway’s case won’t be as deep as building directly in the water’s middle.

“The distance will be such that the bridge won’t affect the beach because most people don’t even swim to that part of the beachfront.”

POTENTIAL ENVIRONMENTAL THREATS

The absence of a pre-vetted ESIA report is more critical when put in the context of the increasingly severe annual flooding in Lagos.

Sea level rise, expert analysis reveals, is expected to hit two meters at the end of the century, putting Lagos and its low/flat topography at risk of completely sinking.

It is estimated that Lagos sinks by up to 87 mm per year. The city’s edges are increasingly being encroached upon for a state with an average elevation of only 1.5 m above sea level.

Eko Atlantic, a project started in 2008, is reclaiming 10 million square meters of ocean land in phases to construct an ultra-modern city shielded by an 8.5 km sea wall. The project, adjacent to Victoria Island and Lekki, was conceived in 2003 as a solution to the Lagos Bar Beach whose perenially overflowing banks had claimed lives and properties.

Siting the project on what used to be Bar Beach was the start of a continued repurposing of beach fronts along the axis that would later drain the recreational water body at Oniru Private Beach, Landmark, The Good Beach, and Sol Beach in VI.

Lagos state touted Eko Atlantic as a project that would convert what could have been a liability to an asset. However, it is also viewed with apprehension among the citizenry, given the scale of ocean land reclamation that experts fear may divert excess water elsewhere.

Portions of the road network at Eko Atlantic are already defined. The Lagos-Calabar coastal highway is divided into different sections, the first and second of which are in Lagos. The first begins at Eko Atlantic’s Ahmadu Bello Road (0.0km) and terminates at Ibeju Lekki (47.5km). The second terminates at the Ogun state border with Lagos.

Frank Nzeh thinks not much has been done about “undue land reclamation” in Lagos and its adverse effects, putting structures at risk.

“The water from sand-filling has to go somewhere. Lekki wasn’t always flooded when it rains, as is now the case,” the engineer said.

Olumide Onafeso, a lecturer of Geography at Olabisi Onabanjo University in Ogun, stated that most of the shorelines in parts of Lagos, Ogun, Lagos, and Ondo are receding due to coastal erosion. He said 80 percent of the stretch for the Lagos-Calabar highway would also have their coastline receding. This, he explained, could be an imminent “disaster” if the road project is improperly executed, especially with reports that have shown that the Niger Delta region is seeing cases of flooding similarly due to coastal erosion.

The EIA expert acknowledges that the Eko Atlantic wall will, in a way, act as a buffer zone that will take the shock of the beach recession in Lagos and prevent adverse effects, although no in-depth study has established how much it contributes.

“It’s purely engineering. We’ve seen road constructions in countries with a large portion of their coast below sea level. But they stabilised it with a solid infrastructure. The shoddy way we do things in Nigeria is why many people are apprehensive,” he said.

Onafeso thinks the coastal highway could ultimately improve tourism and cause a real estate boom in some adjoined states like Ogun.

“I expect that such a road will pass through Ode Omi, a community that should have boomed if not for lack of accessibility,” he added.

NO HOPE FOR LITIGATION

Given that the plan for Eko Atlantic has been in existence for as far back as 2005, Erioluwa Arogundade, a real estate consultant, said it is reasonable to state that the beach water along the Landmark and its neighbouring tourism ecosystem was always going to be sand-filled, whether or not a coastal highway is constructed.

He pointed out that Eko Atlantic had plans to reclaim and fill in an 8.5km stretch of coastline during its phases four, five, and six, extending up to the Twin Waters Tower in Lekki.

“Landmark was simply delaying the inevitable. Without Eko Atlantic and its seawall, the ocean would have eroded the beach up to Water Corporation Drive,” the consultant added.

Arogundade argued that genuine land purchase is accompanied by the acquisition title documents such as C of O or proof of governor’s consent with registered or provisional survey, receipts, deeds of assignments, court judgment, or gazette proving the seller had the right to sell.

Umahi, at the second stakeholders meeting for affected businesses, said the shoreline was illegally subletted. It remains unclear what arrangement the affected business owners had with state authorities.

Onwuanibe, MD of Landmark, declined press interview when contacted on this. Stakeholders representing Landmark’s interests during valuation and negotiations with the ministry of works on structures marked for demolition in the project also declined to comment.

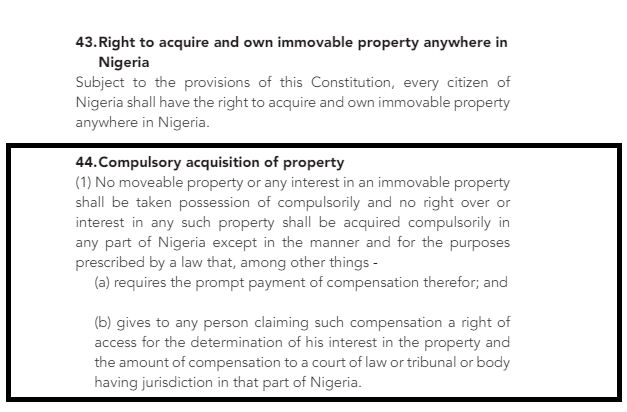

Section 29 of the Land Use Act of 2004 guarantees compensation for an occupier the equivalent of a land’s value in the event of revocation. The right to compensation, rate re-negotiation, and redress in court for a compulsorily acquired property is also provided for under section 44 of the 1999 constitution.

Kesha, the Lagos works controller, classified the businesses to be compensated into those with legitimate claims/licenses to use the occupied land and those whose occupancy could be deemed “illegal”. However, real estate investors observing the development have increasingly faulted the state government for regulatory failure causing untoward pain to property owners. They raised questions on how businesses constructing on the potential right of way for a federal project were never flagged but were allowed to exist for years.

“Anywhere in the world, the state will show up and say you can’t build if your project is found to be sited on unapproved or illegal grounds,” Festus Ogun, a lawyer, said. “But in Nigeria, we allowed businesses to get established before flagging them. That is wrong and malicious.”

Ogun said businesses caught within the right of way must be “adequately” compensated in the interest of fairness and empathy.

“If the compensation by the authorities to give way for the coastal road was not done according to the law and if adequate legal notice was not given, then the invasion of the property would be wrongful. It gives the business the right to redress in a court,” he added.

Add a comment