Women wait in line to cast their ballots at a polling station in Kano State.

Photograph by Sodiq Adelakun

BY OLAJIDE ADELANA, KABIR YUSUF, YEKEEN AKINWALE, EKEMINI SIMON

Before Nigeria’s presidential elections last year, legislator Alhassan Doguwa told raucous supporters what would happen to those who did not vote for his dominant All Progressives Congress party.

“To God who made me, on election day, you must vote for APC or we will deal with you,” he warned to cheers captured on video. “I’m saying it again: On Election Day, you either vote for APC or we deal with you.”

Police in northern Nigeria said soon after that his threats were not idle — he was charged with election-related murders of several people. The deaths were far from alone among the hundreds of violent incidents across the country in the weeks leading up to the election.

Advertisement

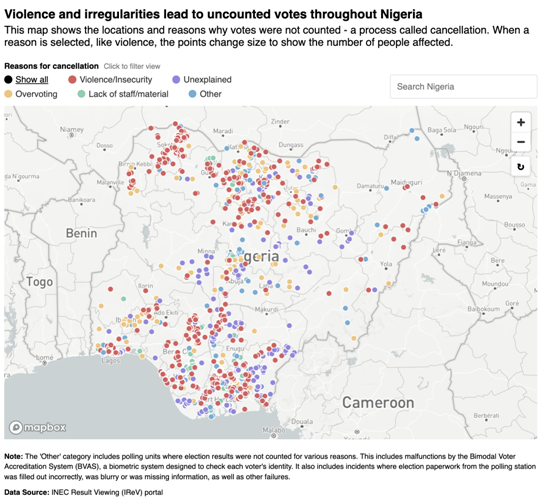

While the Nigerian government’s Independent National Electoral Commission claimed voting was not marred by intimidation, a 10-month-long Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism examination with 20 journalists found widespread incidents of brutality around the country.

Government documents, international observers and dozens of interviews conducted by CCIJ throughout the country reveal a pattern of violence that crippled voter turnout and raises troubling concerns about future elections.

Upwards of more than 100 people reportedly died in election-related violence, according to reports by independent observers. Yet the government’s election commission discounted these deaths and numerous injuries.

Advertisement

In its report released in February 2024, a year after balloting, the elections commission stated, “These elections were notable for their peaceful and orderly conduct, marked by the absence of significant instances of violence.”

It praised security workers, political party officials, election observers and the media for ensuring the safety of voters.

CCIJ reviewed thousands of internal polling site-by-polling site government filings and found more than 2,000 polling stations across the country that reported their ballots could not be added to official tallies because of irregularities. The leading reason, affecting about half the polling stations: violence.

Advertisement

The result is that more than 1.1 million registered voters’ ballots could not be counted in the election, according to government records.

“Violence is a lingering feature of elections in Nigeria,” reported Chatham House the year before the presidential elections.

The London-based NGO outlined how Nigeria’s democracy since 1960 has been “severely weakened” by civil war and years of military rule. Since the end of British colonial rule in 1960, Nigerians have spent about half that time under military rule.

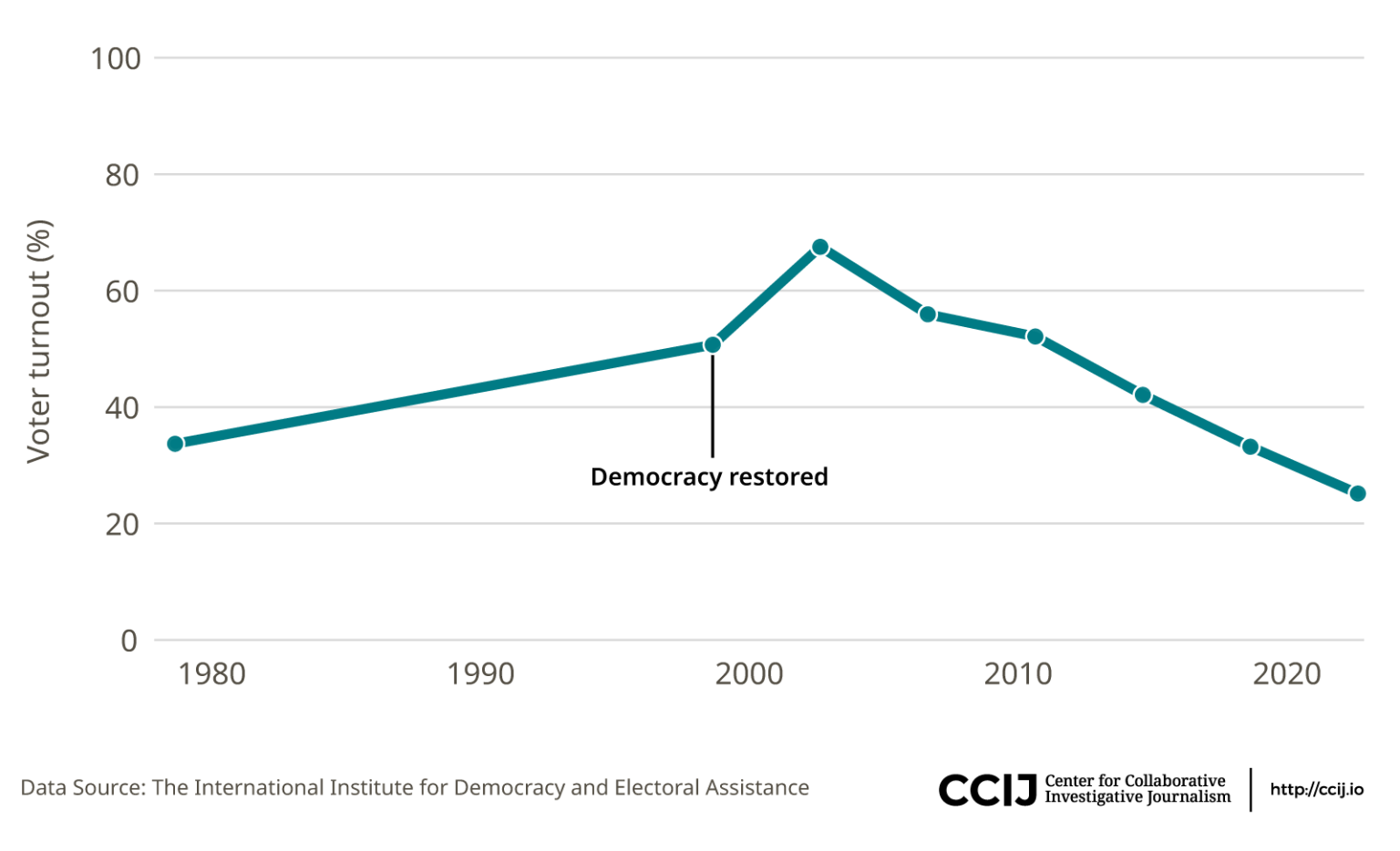

Voting has declined in recent elections, with observers pointing to fewer civil liberties, distrust of corrupt political leaders and weak democratic institutions.

Advertisement

NIGERIAN PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION VOTER TURNOUT RATES SINCE 1978

In 2023, Nigeria recorded a voter turnout of just under 27%, the lowest level since democracy was restored in 1999 and the sixth lowest in presidential elections worldwide since 1945.

Advertisement

The most recent presidential election — the seventh since the last period of military rule ended in 1999 — included irregularities where numerous voting sites did not report results because of violence, lack of proper balloting equipment and other reasons.

That included polling stations in the northern Nigerian state of Kano, near the country’s border with Niger, where the legislator Alhassan Doguwa made his fiery speech in the Hausa language to supporters.

Advertisement

Doguwa was the APC’s majority leader in the country’s House of Representatives, a high-ranking position, and a member of the same party as Bola Tinubu, who won the presidential election in February 2023 for his first term.

Following the election, Doguwa was arrested by police in connection with murders in the town of Tudun Wada. He denied wrongdoing, countering that he was only strongly encouraging voters to support his party, and said the charges were politically motivated.

Advertisement

The Kano state government later dropped charges against him and he then sued the state government and police for bias and wrongfully accusing him of murder and won the equivalent of a little more than $15,000 in U.S. dollars.

Some international observers have estimated that more than 100 people were murdered in connection with the election. The Nigeria Election Violence Tracker maintained by the Centre for Democracy and Development and Armed Conflict Location and Event Data counted 109 election-related deaths in early 2023. The Incident Centre for Election Atrocities put the number higher, at 137.

CCIJ found at least 29 were arrested in connection with election-related violence in Kano alone, and hundreds of others for election-related offenses.

The official polling station reports examined by CCIJ offer a starker picture of the effects of violence than what government officials announced during the elections.

CCIJ analyzed statements state-by-state made by election officials, combing through recordings of election results announcements at the National Collation Centre, Abuja posted to YouTube by Channels Television, which livestreamed the events. CCIJ found officials said publicly that votes were not counted for at least 1,500 polling sites throughout Nigeria. But the government’s own documents show more than 2,000 were not counted because of irregularities and violence.

While officials announcing results mentioned violence and overvoting as reasons for why ballots were not counted, they did not provide figures. But the government documents showed violence was the single leading reason.

Both the public statements and the documents said more than 1.1 million registered voters were potentially affected because votes at their polling sites were not counted.

CCIJ repeatedly sought interviews with INEC about violence and irregularities. Before publication of this story, the agency refuted in its response letter that the election was marred by difficulties.

“The Commission will continue to improve its processes and procedures after every election,” INEC wrote to CCIJ. It did not respond to additional questions.

In its lengthy report, INEC wrote that “in most cases” it addressed challenges involving the late arrival of election materials at some polling sites, inadequate security personnel, violence and intimidation.

The agency, in its report, called the election “is perhaps the best planned and most innovative election in Nigeria.”

“The election witnessed the highest number of eligible voters and voting locations across the country with the participation of over one million election duty officials and deployment of enormous logistic requirements including over 100,000 vehicles and about 4,000 boats protected by gunboats,” according to the agency.

Along with murders, there were countless incidents of intimidation and irregularities that prevented people from casting ballots.

Nigerian police barricade the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) collation center following alleged reports armed men were planning to invade and disrupt the center after Nigeria’s gubernatorial election in Kaduna State.

Photograph by Sodiq Adelakun

On Election Day in 2023, in the district of Chiranchi, about 70 miles south of Tudun Wada, where the Kano governor alleged Daguwa was linked with the murder 15 people, 30-year-old Muhammad Ibrahim was in a line at his polling station, excited to vote for the first time.

The morning’s peace was shattered.

A wounded man ran through the crowd, pursued by a violent group armed with sticks and knives.

Ibrahim recalled a bystander asked if he intended to cast his vote for the APC.

Ibrahim said the man told him, “They’re targeting those who want to vote for the NNPP,” the New Nigeria People’s Party, which was among the leading opposition parties.

Ibrahim was among those who ran, fearful for their safety.

CCIJ could not verify claims that the APC was connected with the menacing group that chased away voters. Police declined to comment on incidents of violence in the state of Kano.

Meanwhile in Gwale, Kano, about six miles east of where the 15 people were allegedly murdered in Tudun Wada, journalist Ashiru Umar recounted witnessing threats to voters.

“They were intimidating all voters that were not supporting APC,” according to Umar.

He said he was attacked and beaten by thugs for conducting interviews for election stories and sustained injuries that required more than a month of medical treatment.

“We managed to leave the area,” he said. “All this happened while the security agents were watching.”

Election officials also faced violence.

Aisha Abubakar, who served as the independent election commission’s presiding officer in Kano, said thugs attacked her workers before voting began, resulting in severe injuries to two colleagues.

“There was a miscommunication regarding where we would set up election materials,” she said. “We were trying to give clarification, then suddenly, political thugs said we were trying to manipulate the process, and they started beating my polling unit officers.”

In the electoral commission’s filings reviewed by CCIJ, at least 16 polling stations in Kano reported violence and did not count ballots for several thousand voters. In many other instances, poll workers did not give reasons for why no ballots were counted at their locations.

And Kano was far from alone from reports of intimidation.

THE NIGERIA ELECTION VIOLENCE TRACKER COUNTED 109 ELECTION-RELATED DEATHS IN EARLY 2023

Photograph by Yusuf Ayuba/CCIJ

VIOLENCE IN NIGERIA’S LARGEST CITY

Bina Jennifer Efidi said she barely escaped death when she went to vote.

She went to vote at her polling station in the Surulere area of Lagos, a vibrant section with bars, clubs and a national arts theater.

“When I went there, voting had already commenced, people were already in the queue and I went for verification to be sure that it was my polling unit,” she told CCIJ.

But then, she said, about 20 youths were standing by the polling station on Dipolubi Street and began moving to one of its exits. They began shooting guns and disrupting voting.

She was hit on the right side of her face.

“I was hearing gunshots,” she said. “I thought I had been hit by a bullet.”

She could not remember what kind of weapon was used to hit her face.

“I held my face and blood was already dripping down; people were running helter-skelter and me too, I had to stand up and look for help because I had been injured.”

She went to the hospital and got stitches for her cuts.

On her way back home, she saw voting had resumed at the polling station.

“When I saw that, I felt that this was what I wanted to do to make my vote count, and despite all my struggles,” she said. “I had to cast my vote.”

Efidi says she did not know whether any political party was connected with the attackers or who was behind the violence.

“I’m not a politician, I only came out to vote. I have no idea who sponsored them but it was obvious that they were touts or thugs,” she said.

She said there were no security officials to prevent the attack. She hopes the Nigerian government increases security for future elections so elections would be “free and fair.”

A few miles north, in Lagos’ Fadeyi neighborhood, Ayo Oladiran, a resident there, said many voters were chased away from their election day polling site.

Photograph by Akintunde Akinleye/CCIJ

Oladiran recounted how youths known as Area Boys went to the polling station and demanded that those who would not vote for ruling party candidates should leave.

“Area Boys came and said those that will not vote for Tinubu should leave and Igbos should go back to their land,” Oladiran said. “They said if you are Igbo and from Anambra, go back to your state.” Igbo people are mainly from southeast Nigeria, including the state of Anambra.

They were largely unarmed. “Although one was carrying a stick, they typically don’t need to display weapons because their reputation alone instills fear in the local residents,” according to Oladiran.

Security workers did not try to stop the threats, she said. “Police officers were just there, not moving,” she said. “They didn’t do anything.”

A few miles further north, in Lagos’ Orile-Oshodi ward, journalist Oluwakemi Adelagun, who works for Premium Times, one of Nigeria’s leading news outlets, checked on a polling station inside St. John Primary School.

She visited shortly before 2 p.m. but saw no voters despite hundreds registered to cast ballots there. She took a photograph to document the scene.

She asked an election official about voter turnout, and an unidentified man started cursing her. She explained she was a journalist reporting on voter turnout. A police officer was watching nearby, and she believes his presence is the reason the incident did not turn violent.

In the end, the two polling stations inside the Methodist school reported 75 ballots cast out of more than 1,400 registered voters.

In the Festac section of Lagos, resident Oluchi Anyawu left home with her family to vote but they were chased away by Agberos, the name given to youths who work at motor parks, where people get rides on buses and minivans.

“We weren’t even allowed to reach the polling unit,” she recalled. “There were numerous Agberos in the area, insisting that only people from a certain tribe could vote, which was quite unfair. We are equals in Nigeria.”

VIOLENCE IN THE SOUTH-EAST

A couple hundred miles southeast of Lagos, assailants disrupted voting in the Obio-Akpor part of Rivers State.

Abhulimhen Thompson, the elections officer at a polling unit, reported in a government filing submitted to the country’s computerized balloting system that they were thugs hired by political parties who were losing contested elections.

Although Thompson and his colleagues escaped unhurt during the attack, thugs took away the presidential and federal legislative election ballot results from the polling site.

“All sensitive and non-sensitive electoral materials we took with us were scattered, destroyed, and snatched away,” he recounted.

About 60 miles east, in Yenagoa, the capital of Bayelsa State, voters became angered when election officials did not show up at polling stations.

Mahmood Yakubu, the national election commission chairman, said the incidents involved 140 polling stations, and security workers were unable to calm protesters.

He rescheduled elections in the affected areas for the next day.

Not everyone returned to cast their ballots.

“I could not vote because of the crisis,” said Ugochukwu Godwin, a voter in Yenagoa’s sixth ward.

“The next day, I didn’t even bother due to the distance from my residence to the polling unit,” he said. He recounted those authorities’ increased security, but that did not give him confidence.

“I was worried for my safety,” he said. “I thought it wiser to be safe than sorry, so my family and I stayed back.”

Throughout Bayelsa State, voter turnout was low, with only 16 percent of the more than one million eligible voters casting ballots.

In Nembe, Bayelsa State, four individuals were charged with terrorism and promoting violence in connection with the deaths of three people in the days leading up to the presidential election, including the murder of a Queen Kieriseiye, according to news accounts confirmed by CCIJ.

One source told CCIJ that Kieriseiye was pregnant at the time of her death.

Closer to Lagos, in Idanre, Ondo State, Owoeye Beatrice said violence interrupted voting at her polling station at a maternity center in the city’s Alade Atosin neighborhood.

Photograph by Sodiq Adelakun/CCIJ

Beatrice said she suspected the incidents stemmed from “old scores settled” among loyalists of rival political parties.

In the end, her polling station saw 36 percent of its registered voters cast ballots. That exceeded the national rate of 27 percent voting in the presidential election.

A DEATH IN AKWA IBOM

Further southeast, closer to the country’s border with Cameroon, in Etim Ekpo, Akwa Ibom State, 45-year-old Uduak Udo left his home early to vote, and to ensure ballots at his sixth ward voting station were not missing.

His wife, Florence, said neighborhood thugs went to polls and announced that supporters of the Peoples Democratic Party would not be allowed to vote.

Violence ensued among supporters of different political factions. She ran home only to learn later that her husband was dead.

She said witnesses told her that supporters of other political parties had killed him and that security workers did not attempt to rescue him.

“Those who killed him still move around freely without justice,” Florence said.

“I don’t think I will ever participate in any future election or allow my children to ever participate. Nigeria’s elections have become battlegrounds where you must kill to survive.”

In the end, no votes from the area’s 11 polling sites were counted because of “disruption,” leading authorities to declare an emergency.

Elsewhere in town, youths armed with axes, cutlasses, and bottles attacked the election officials at one Ward 6 village hall voting site, causing panic and forcing voters and election officials to flee.

Ime Ukpong, a local legislative council member, attempted to rally election officials and voters to return. Attackers shot at him.

“Those people were not using masks. It was a broad daylight disruption. But to date, no one has been arrested,” he told CCIJ.

Photograph by Akintunde Akinleye

INTIMIDATION, ARRESTS, MISSING BALLOTS

Rashida Owuda, a political scientist and lecturer at the Prince Abubakar Audu University, more than 300 miles northeast of Lagos, said the “overt presence of security forces” in the Ayingba neighborhood next to the university discouraged voters from going to the polls.

“They made it look as if it was a war zone, and that atmosphere made people feel intimidated,” she said. “The mere presence of the military was enough to stop some women from going out to vote.”

She cited as evidence the low voter turnout.

“If you look at the total number of people registered and those who voted, there is a great disparity. And that is because people felt intimidated.”

Out of an estimated 27,000 eligible voters in Ayingba, only 12 percent voted, according to the election commission’s data. Twenty-two of 73 polling stations also did not report any ballots cast in part due to violence.

Others complained about problems with voter registration.

Odiji Okpanachi, who teaches political science at the same university as Ohere, said the government mishandled his voter registration when he moved to work at the school. The lack of the card prevented him from voting.

“Unfortunately, I didn’t vote in the last election because we are in a country where people register as voters but they never get their cards” that identify them as eligible to vote, he said. “I am one of those people that didn’t get their voter cards.”

He finally got his registration card well after the presidential election.

Charles Oke, a PDP ward chairman in Mbaitoli, said ballots and other election materials were unavailable for voters at his polling station. Oke called the election unfair because voting was compromised.

In Rivers State, a widely circulated video showed policemen in a Toyota pickup truck seizing ballot.

Stakeholder Democracy Network, a nonprofit, said the video was disturbing, and its workers witnessed similar incidents in Rivers State.

Grace Iringe-Koko, a police spokeswoman, said on Feb. 27, 2023, that authorities arrested four officers for interfering with the election.

“Rivers State Police Command has arrested and taken into custody one officer and three Inspectors for interrogation. The police pick-up van in the trending video has also been impounded for a thorough investigation,” Iringe-Koko said in a statement.

In December, CCIJ contacted Iringe-Koko for updates on the arrests. She declined to comment on the case.

Mark Usulor, the election commission’s head of voter education and publicity in Rivers State, said election materials were deployed to all polling stations across the State. He blamed the violence on thugs and politicians clashing among themselves. He declined to discuss details about specific polling stations where ballots were not counted.

Women approach a security official for a passage to their polling station in Kano State.

Photograph by Sodiq Adelakun

INTERNATIONAL OBSERVERS CONCERNED

International observers raised concerns about violence suppressing voting. Human Rights Watch issued a dispatch, “Nigeria’s Elections Remain Risky for Many Citizens.”

Amnesty International called for the government “to investigate widespread violence unleashed on voters in parts of Lagos, Rivers, Kano, Edo and Delta states. Those behind attacks on voters, journalists and electoral officials must be brought to justice through fair trials.”

The United States Embassy in Nigeria said it is “deeply troubled by the disturbing acts of violent voter intimidation” in Lagos, Kano, and other states.

The embassy issued a statement that, “the United States joined other international observers in urging the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) to improve voting processes and technical elements that experienced flaws in that voting round.”

It called for Nigerians to work together “to strengthen the country’s vibrant democracy.”

The International Republican Institute and the National Democratic Institute noted that observers witnessed suppression, violence and intimidation in at least 18 states.

“In Abia and Bayelsa states, violent disruptions resulted in suspension of voting in several hundred polling units,” they reported. “Lagos suffered multiple attacks throughout the day, including an attack on a collation center, potentially disenfranchising a large number of voters.”

The European Union Election Observation Mission in Nigeria reported that “voting was critically delayed by the late arrival of sensitive materials.” It also criticized procedures for transparently tabulating results.

Ezenwa Nwagwu, the head of Partners for Electoral Reform, said intimidation and violence were not the only reasons for low voter turnout. Voting is not mandatory, he said, and many Nigerians facing hardships are losing faith in democracy.

“Nigerians are disenchanted by the lifestyle of elected political officeholders when many live in abject poverty,” Nwagwu said in an interview with CCIJ. “Democracy is suffering a deficit. It is not fulfilling for most people.”

and count votes in Kano State.

Photograph by Sodiq Adelakun

‘IT BROKE MY HEART’

On Election Day in Imo State, Joseph Ikenna recalled seeing thugs among a crowd as early as 8:30 a.m. at a village hall polling station in Njaba.

“Vote for the APC or leave,” they ordered, with one of them brandishing a firearm, Ikenna recalled.

Nigeria’s election commission did not count votes from that polling station because of irregularities and Imo State recorded the most number of votes that were set aside because of violence and irregularities.

“It broke my heart that all our sacrifices that day were in vain,” Ikenna said. “Some of my relatives who traveled all the way from Kano and Lagos back home to vote never had their votes counted because, in the end, INEC (the government election commission) had to cancel the election in the unit due to disruption.”

The event devastated him.

“I don’t think we will ever come out to vote in any of Nigeria’s elections again.”

Inibehe Effiong, a human rights lawyer based in Lagos, said there is an option available for voters who faced voter suppression. He said such individuals with concerns about voting-related violence, intimidation and other problems can contact his law firm, Inibehe Effiong Chambers, for possible legal recourse.

LEARN ABOUT OUR DATA METHODOLOGY

To examine the scope of violence, irregularities and other causes that led authorities to not count votes at certain polling stations in the 2023 presidential election, CCIJ downloaded all the reports filed by polling stations throughout Nigeria with the government’s Independent National Election Commission’s online database, IREV.

The documents were downloaded by CCIJ in July 2023 using python, a computer programming language. Many of the reports included officials making notations by hand. The handwritten notes were extracted using Google Pinpoint’s handwriting recognition capabilities.

In Nigeria, form EC 40G is used by election officials at a polling site when they declare voting at the location is canceled — which means votes will not be counted. The form includes categories for election officers to indicate why votes were not counted, including overvoting — when more ballots are cast than there are registered voters for a polling site — and violence.

CCIJ conducted a comprehensive keyword using Google Pinpoint to cull the documents, using terms related to why votes were not counted, including “cancel,” “canceled,” “cancelled,” “EC40G,” “no result,” “overvoting,” “disruption,” “no results,” “violence,” “disruption,” “over voting” and “no election.”

CCIJ reviewed each document flagged in these searches, setting aside false positives, to ensure no computer errors affected the review.

The documents were then extracted into a spreadsheet for detailed analysis.

CCIJ also found documents uploaded to IREV that were blank papers with handwritten notes stating “No election” or “No result” without specifying a reason.

INEC has since removed many of these documents from its IREV website.

CCIJ also obtained INEC’s 2023 data on registered voters for each polling location. which was published on their website but later removed.

To assess the impact of violence and irregularities on registered voters, CCIJ used the 2022 registered voter data along with the reports of polling stations where votes were not counted in the presidential election, enabling CCIJ to quantify the potential effect of cancellations.

Download and view the data for further analysis and review:

BEYOND THE FECADE – CCIJ DATA ANALYSIS

This story was produced with the support of MuckRock and the Filecoin Foundation for the Decentralized Web.

Add a comment