Within three hours on February 23, Taiwo George, TheCable’s news editor, witnessed the death of two children at the Oncology unit of the pediatric ward of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH), Idi-Araba, Lagos.

A week later, he was back at the same ward to witness the death of two others. Worried by the number of lives lost to the passive response of health workers to emergencies, George returned to the hospital a few more times – and even found some time to donate blood to a child who, sadly, eventually passed on.

“I mopped her body; I mopped her body!”

Those words were the wails of the mother of Pelumi, an eight year-old child who passed on in the wee hours of the day, owing to late medical response.

Advertisement

Pelumi was the last survivor of the set of 14 children who underwent treatment at the hospital after they were diagnosed with cancer in 2014.

DYING HOURS OF A SICK CHILD

A few hours to her death, Pelumi’s mother was hesitant in giving her water to drink, probably in line with medical advice.

“Please let me drink water; mum, please let me drink water,” she begged. The mother eventually succumbed.

Advertisement

Hours later, the girl started gasping for life. The doctor on housemanship, who was on call, rushed to her bedside but not after five minutes had passed. Two nurses, who had been resting in one of the rooms, rushed in. They were later joined by two senior female doctors but all this could not bring Pelumi back to life. Perhaps she could have survived if help had come at the right time.

The young doctor documented the little girl’s death and moved over to Temilolu Fadodun – the next victim – who was wide awake all night after undergoing blood transfusion.

Pelumi’s dad, who had earlier been briefed about the situation, walked into the ward at that moment. It was a few minutes past 5am. From the looks on the man’s face, it was obvious his sleep had been interrupted.

After listening to the doctor, he placed both hands on his head, screaming: “You people have killed this child.

Advertisement

“You wasted her life. I was complaining of inadequate attention last night and no one cared. See what this has resulted into. You refused to monitor her after dousing her with so much chemotherapy. You told me you couldn’t do surgery here and I took her outside, only for us to return here and have this. See how you killed my child!”

GOD IS NOT TO BLAME

He refused to be swayed by the appeal of the health workers who wanted him to accept that his daughter’s death was God’s doing.

“Don’t tell me that,” he snarled, staring at Pelumi’s lifeless body. “I am a man of God. Don’t bring God into this. You people killed my child.”

Although the mother of the child had been taken to a corner, where she was surrounded by sympathisers, her cries pierced through the entire ward.

Advertisement

“Pelumi has turned to a corpse; my own Pelumi is gone forever,” she said in Yoruba.

Temilolu’s dad was very bitter, not just with the medical workers but also parents he said were failing to learn from the tragedy of others.

Advertisement

“Few moments after a child passes on, you will see other parents carrying on as if nothing happened,” he told TheCable in an anger-laden tone.

“I’m sure these parents will soon start playing with the health workers. It’s only someone who loses his child that knows the pain. You see other parents laughing with the doctors and nurses after such tragic encounters, instead of uniting to condemn their lackadaisical attitude to work. See how they killed that child; only God knows who is next.”

Advertisement

Sadly, the man who had been running helter-skelter not just throughout that day but for several months was the next in line to feel the pain that was being spoken of.

‘MINOR’ CANCER

Temilolu, the second fruit of a four-year union, was a cheery child until one evening in December 2015 when his mother noticed an unusual growth on his stomach. Quickly, she rushed him to Ebute Metta Health Centre, a few metres from her house, and a doctor assuaged her fears.

Advertisement

“The doctor said it was nothing. He even mocked me for bringing my child to the hospital because of ordinary swollen tummy,” she explained.

“I told him that the situation was unusual. Then, as if to prove what he said, he pressed my son’s tummy, and my baby laughed. It made myself feel everything was okay.”

But the abnormal growth continued to blossom, and she was forced to seek medical advice at a second hospital, where she was then referred to LUTH.

LUTH recommended a series of tests and in the end, it was discovered that the child was not just dealing with “swollen stomach” but – wait for it – cancer of the tumour. For 13 consecutive days, he was placed on admission.

Two weeks later, the worried mother was told her son could go home, but they needed to return for reassessment after two weeks. As it would happen with any mother, she left office in glee, not knowing that on her return, she would be told that the 13-day treatment had yielded no result. Her sorrows began afresh.

HOUSE DOCTORS EVERYWHERE

“They started the new round of treatment by administering chemotherapy on him and when the process was over, there was no one to attend to us,” she said.

“Unlike the previous times when they would take his blood samples for tests after chemotherapy, there was no doctor on call. Perhaps because it fell on a weekend, doctors don’t normally stay during weekends, except in situations when they have to administer chemo on a child.

“It’s student (house) doctors who are usually around during weekends. Even on weekdays, regular doctors close at 4pm, and are hardly seen afterwards.

“My child finished his chemo late Saturday and around 8am on Sunday, I noticed he was pale. So, I started looking for a doctor. Luckily, I found one female doctor administering chemo on a child. I approached her to explain that my child needed urgent attention. Although she sounded compassionate, she didn’t examine the child; she only told me to patiently await the arrival of another doctor.

“She told me that she only rushed to the hospital to administer that chemo and would be leaving as soon as she was done because her husband and children were waiting for her at home. She said they wanted to go to church.

“She called a junior doctor to attend to me but that one said he was attending to another child. I left for the ward, but upon seeing my child, I couldn’t stand the situation, so I returned there again but the junior doctor said he was still busy.”

The bereaved mother said while waiting for the student, she saw another doctor walk by and she approached him with tears in her eyes. That one, too, did not listen.

“I had to wait for the student, who didn’t finish until six hours later.”

The test was conducted at Pathcare laboratory, outside LUTH, “because the hospital’s laboratory was not in good shape”, and the result showed that the child had 12 per cent PCV (packed cell volume), whereas an average child needs above that, depending on a wide-range of factors.

By the time she returned to the ward with the result, no doctor was on call. She would wait for another hour before receiving the attention of another junior doctor, who recommended that they get blood for the child as quickly as possible.

HOT CHASE FOR BLOOD

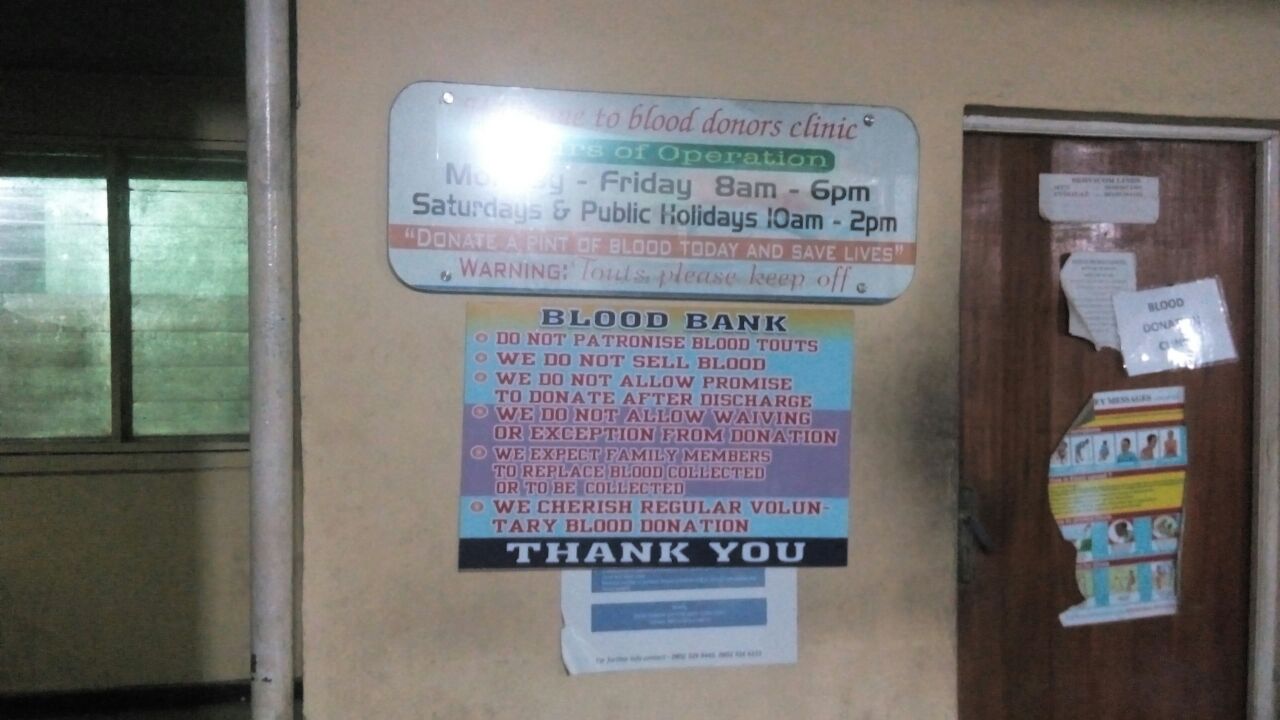

The child desperately needed blood but LUTH’s blood bank was empty. The next available option was the Isolo General Hospital, which was half-an-hour away.

Temilolu’s father was hurrying to Isolo when he bumped into a woman whose child had a similar challenge.

“She explained to me that the doctors said the blood she bought for her child, whose PCV was 25 per cent, would only be available after three days because it had to be screened,” he told TheCable.

“Considering that my son’s case was critical, I foreclosed the option of buying blood. I could not donate to him, because I am A+, while his own blood group is O+. We tried the mother and realised that she also was incompatible.”

The parents were able to find a relative whose blood group matched Temilolu’s. But one hour after the donor arrived, there was no doctor to take his blood sample for screening.

Collection of blood sample and laboratory analysis gulped another two hours and to worsen matters, no doctor was available to receive the result of the test when it was finally released.

‘LUTH AS A DEATH ZONE’

Tired, frustrated, dejected, Temilolu’s father handed the result to his wife, who reached for her phone and called the doctor. The doctor ensured the conversation didn’t last 30 seconds.

“He hung up on me, saying we are not the only ones who need service, that he was at ward D2 attending to other children,” she said soberly.

“Is it their fault? I just pray that God should heal my child so that we can leave this place on time. LUTH is not a place I want my enemy to visit.”

After much persuasion, which involved a personal visit to D2, the doctor returned to Temilolu’s ward. But how wrong were they to think that the transfusion would commence immediately!

Not even appeals of “emergency” changed a thing. The house doctor explained that he needed to secure the approval of his superior to commence the process.

Sadly, his superior was not around and had not been answering her phone, so the house doctor went to her quarters. The senior doctor arrived in the company of another colleague, but after examining the result for about five minutes, they whisper to each other and then announce their dissatisfaction with the failure of the examiner to write that the willing donor was capable of donating. The transfusion could still not proceed.

The father returned to the laboratory again. In all, a child in need of urgent attention waited more than 15 hours before the process commenced.

TRANSFUSION COULDN’T SAVE THE CHILD

The doctor explained that the process on Temilolu would last four hours but it stretched into the fifth hour because he was also attempting to restore a dying Pelumi to life. Not minding that it was time for their child to receive another dose, Temilou’s parents joined others in praying for the salvation of the girl’s life.

About an hour after the transfusion ended, Temilolu’s breath suddenly began to gasp for breath. The nurses were called in, and they oxygenated him. But 15 minutes later, he gave up the ghost.

AND THE DEATHS CONTINUE

A parent, who did not want to be named because his child was still receiving treatment at the hospital, narrated how another child died in similar circumstances, two days after the deaths of Temilolu and Pelumi.

According to the parent, the mother could not get blood within the hospital, so she rushed outside, leaving her daughter in the care of nurses. By the time she returned, it was a corpse she met.

A week after the death of the three children above, this reporter encountered a man bearing the corpse of his newborn child. Surrounded by relatives and friends, he wept uncontrollably.

A family member said the baby’s mother was still unconscious at Ikorodu General Hospital, where she underwent caesarean operation.

The birth of the child had been pre-mature, prompting the need for an incubator. Since there was none at Ikorodu, they were referred to the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital (LASUTH) in Ikeja, where response was fast.

“When we got to LASUTH with our referral letter, two doctors attended to us. They explained to us that they did not have incubator and asked us to go to LUTH. They assured us that the baby would survive,” he told TheCable.

“At LUTH, they refused to attend to us; they were just pushing us about. Imagine? And this was supposed to be an emergency. They first said the doctor was not available, but they later requested to see our letter. After a while, they told us to wait – different forms of excuse.

“After about an hour, a house doctor came in and examined the child and it was then that we were told that the baby had died. We were later informed that the delay was because they did not have oxygen.”

As the relative of the deceased child was narrating his experience, another child was being brought in.

“How old is she?” One of the nurses asked. “Fifteen years old,” replied the mother, who was some metres away, apparently because she was tired after trekking a long distance.

DISRESPECT FOR EMERGENCIES

The distance, by foot, from the main entrance to the children emergency ward is some seven minutes. No wheelchair, no trolley, no space for ambulance to move in, no medical workers to assist. No provision whatsoever for emergency.

Two able-bodied men carried the 15-year-old girl, while the mother and her sympathisers walked behind.

The child was left unattended to. Only the mother went inside the ward; the sick child lay on the bare floor somewhat unconscious. After 10 minutes, they were told that there was no oxygen, and again the two men lifted her.

“She no dey breathe well again o,” one of the men cried out. Quickly, they drop the child to feel the pulse of her heartbeat, which they said had stopped, and the lamentations poured out louder.

AND LUTH PUNISHED THE BEREAVED…

Bereaved parents react to their losses in different ways; some with anger, some with tears; others resort to violence.

The man, whose son had the misfortune of living for only a few hours, fell in the last category.

“I will destroy you people; I won’t take this. Someone must pay for this,” he yelled.

Attempts to calm him down yielded no result; and he went ballistic when a nurse insensitively told him to stop disturbing the peace of others.

“I am going to write a petition against you people,” he threatened.

“Go ahead if you like; just let others have peace,” the nurse replied.

Security agents intervened to prevent total breakdown, but the man had already created a scene that authorities of the hospital were unwilling to overlook. He was detained by the security men, and the authorities subsequently threatened to charge him for assault. His family members wondered if assault was anything compared to negligence leading to preventable death. The case was not resolved until the third day, both parties refusing to disclose details of their meeting.

Meanwhile, Temilolu’s father did not want his child to be taken to the mortuary. “You killed my boy, let me go and bury him,” he moaned.

But the hospital refused. Moments later, it was discovered that their refusal was to ensure the payment of every kobo owed. Parents have to clear all outstanding bills before the corpse of their child is released, even if sheer carelessness was responsible for the death.

HUMAN BEINGS AS EXPERIMENTAL MATERIALS

Another parent, who also refused to disclose her identity, said the hospital was using the children for experiment. She said 85 per cent of the doctors who attended to them were house officers – a claim that other people corroborated.

She said that most of the young doctors not only lack compassion, but are inexperienced. The woman narrated how her child’s complexion suddenly changed after a house doctor administered blood transfusion – a process that should have lasted five hours – in 30 minutes.

“I noticed that his eyes were turning, the colour of his skin had turned to red. Immediately, I raised the alarm and the doctors came in to examine him,” she said.

“While they were doing that, I called my uncle who is a medical doctor in the US and he asked me a couple of questions. He told me the transfusion was the problem.

“Though the health workers tried to hide this from me, I told them what my uncle said. It was only God that helped my child to survive that terrible experience.”

Another parent recalled how she cautioned a doctor on internship who wanted to apply drip on her child in a wrong way.

The doctor, she said, initially argued but eventually succumbed to superior reasoning. Having been by the bedside of her sick child for years, the woman had observed how doctors applied drips and it was clear to her that the interning doctor was doing it the wrong way.

Below is how yet another parent narrated his own encounter.

“A student [house] doctor came to take blood sample from my child and I realised that the sample he took was very small. I told her that the sample wouldn’t be enough but she just ignored me.

“Later, the matron came in and complained about the quantity; they had to inject my baby to get additional sample. Is it not clear that these baby doctors are supposed to be under strict supervision?”

True to the claims, it was observed that the house doctor who performed the transfusion was asking for clarifications from a superior moments before executing it. As if to prove his incompetence, the doctor who gave him approval cautiously asked if he was sure he could carry out the process.

NOT THE IDEAL HOSPITAL

The nature of the wards and the general state of facilities are stories for another day, torn mosquito nets on windows, congested bed space for patients and lack of it for parents and relatives nursing the sick (it is commonplace to see family members and friends of patients sleeping in the open), offensive odour from wards, water-logged toilets and bathrooms, pharmaceutical stores without drugs, non-functioning laboratory and epileptic power supply are the main features. Although LUTH is highly regarded among the 22 teaching hospitals in the country, it is a far cry from what an ideal hospital should be.

Also, there is the situation where people are diagnosed with life-threatening ailments but are told that treatment cannot commence until months later due to a long list of patients awaiting treatment

The only place where things seem to be working in LUTH is the E Wing, which is more expensive than some private hospitals. The wing was created under private establishment, and it is used by high-profile patients, leaving the poor wondering if they do not have a right to life.

When TheCable reached Kelechi Otuneme, spokesman of LUTH, to know if the management of the hospital was making efforts to address some of the problems, particularly the professional misconduct of workers, he gave the impression that the complaints were fabricated.

For him, the hospital was performing beyond expectation in all regards, and was doing its best to save lives.

“What you are saying is wrong; it’s not true,” he told TheCable in a phone conversation.

“I find it very difficult to believe these things. It is not true that we do not have oxygen in store. That is not true. We always have oxygen.”

When he was told that these complaints were witnessed live and they weren’t just hearsay, Otuneme changed his line of defence.

“Anybody who is complaining or writing anything against LUTH now is inhuman. A lot of changes have been made in recent times,” he said before ending the conversation, claiming that he was at a ceremony and the discussion could hold later.

The next time he was reached, he insisted that the claims were untrue, but said he could not go into details as he was driving.

Other attempts to reach him were unsuccessful.

THIS IS A NIGERIAN PROBLEM

A woman, who chose to be anonymous, narrated how she lost one of her twins to sheer carelessness of health workers.

“To the glory of God, I was able to deliver a set of twins without cesarean operation at Ikorodu General Hospital. But when the children came out, my mother noticed that the breath of one of them was abnormal,” she said.

“We alerted the nurses and requested that they oxygenate him but they said nothing was wrong with the child. In less than an hour, the situation worsened. They started running helter-skelter; but before they could bring oxygen, the child had given up.

“They are so used to such situations. Without sympathy, the most senior nurse just asked them to pack up the child. As a matter of fact, you hear them give instructions to pack corpses frequently. ‘Pack, pack, pack’, they keep dishing out orders.

“Human lives mean nothing to these people. I am so scared of these hospitals.”

FOUR PATIENTS AT ABUTH DIE ON A NIGHT

There was a case when all the four patients at the intensive care unit of the Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital in Zaria, Kaduna state died in one night.

A hospital source told TheCable that oxygen supply suddenly went off and those in charge were nowhere to be found. A call was put through to a very senior person in the hospital management board, who was able to get those in charge to restore the line.

“When those who came to restore the line were asked, they said they had been working all day and they needed to rest,” the source said.

“Two hours later, around 2am, there was power outage and the supply was interrupted again. This time around, they couldn’t reach those in charge because their lines were switched off.”

HEALTHCARE IN NIGERIA BEHIND THE REST OF THE WORLD

A Nigerian who has relocated to Canada, narrated the gulf in the healthcare system of both countries.

“I had my first child at the Military Hospital in Ikoyi, Lagos, and the experience is what I will not like to have again,” she said.

“The environment was not conducive; the table where I was laid upon was wedged with stool. The room was also stuffy.

“But when I was admitted to Royal Alexandria Hospital in Edmonton Alberta, Canada, I had a room to myself. There were two doctors and five nurses attending to me.

“Canadian standard is obviously ahead of Nigerian. I give you this example. While at Alexandria Hospital, there was an emergency case that was brought in. You needed to see the way doctors and nurses rushed there; you would think they were in a car race. Here, no one jokes with emergencies. Health workers are very dedicated to their job. The aftercare is also impressive. When I left the hospital, a nurse still visited me at home.

“In Nigeria, I didn’t experience anything close to that, and to think we paid our way through. But here in Canada, we didn’t spend a dime. The Canadian hospital is also a public hospital just like Ikoyi military hospital… They prioritise children; they don’t joke with the lives of children here at all. It’s not as if children don’t die here, but death here must be the result of something really serious.

“I had an experience back in Nigeria shortly before we relocated to Canada. I went for a scan and I saw a woman who was in labour. They told her to go for a scan; imagine, that was someone in labour! There wasn’t even one nurse to assist her; no one to put her through. It was a relative who assisted her; she was already in pains.

“To worsen things, when she got to the laboratory, there was no one to attend to her, so she started crying. When the official who was supposed to attend to her came in, he barked: ‘Wetin dey make you cry? Na today? Abeg clean your eye. When you dey do am e no sweet you?”

“Tell me, are you supposed to say things like that to someone in labour? And that’s supposed to be a professional! Such thing can never happen here in Canada. There’s just a lot of difference.”

IN DEFENCE OF DOCTORS

A doctor, who works in one of the teaching hospitals in the north, spoke to TheCable but asked not to be named.

She admitted that the system is indeed damaged, but said most people blame health workers because they are the ones they see. She maintained that if most doctors had their way, the situation would be quite different.

“Generally, the health system in Nigeria is yet to achieve its potential, not because the manpower is not qualitative, but because the manpower available compared with the patient workload is nothing near global best practices,” she said.

“It therefore means that any doctor you come across in the clinic is overworked. In the teaching hospital, you find a doctor taking a call from Saturday to Sunday all through Monday, and in the delivery section you can have 10 cesarean sections in one day.

“So, this doesn’t really help us to bring out the best; the work environment is not conducive enough. There are lots of hospitals that have not employed new doctors in the last four years. And the older ones have taken their examinations and passed. Some have even left the system.

“Yes, the management talks about financial constraint, but if you cannot get new doctors, what about replacing those who have left? This is a crucial issue but they sweep it under the carpet under the guise that there is no provision for it in the budget. So, if you used to be 10 in a unit and you are now five, the responsibility of others falls on those remaining, and how do you expect the best? The hospitals are short-staffed.

“Look at the issue of emergency, you expect a patient in that situation to see the doctor immediately, but that cannot happen. The doctor is there but the bureaucracy won’t allow it. The patient needs to get a card; the card needs to be presented. There is the bottleneck of standing in a queue; nobody gives preferential treatment, even to staff. It’s so chaotic that one has to go through the process irrespective of whether the case is an emergency. This kind of situation doesn’t help us to manage critical situations because there are patients for whom every minute counts.

“Something really needs to be done about this because a lot of people are dying as a result of the current situation. Several undocumented deaths are happening, so the management of the hospitals should look into this. There are emergency cases that should receive attention even before cards are available.

“Look at the issue of consumables. Can you imagine a patient that is in urgent need of blood and there is nowhere to get blood? A doctor has to recommend that the patient buys blood, but what happens in a critical situation where the patient doesn’t have all that time?

“So, the situation poses a very serious challenge to the health practitioner because you are seeing a patient, and you know that you can make an intervention. However, there are certain things beyond you. The issue of our welfare is also there. Doctors are not treated well in this country. We are not appreciated. If you look at the staff structure, doctors are the fewest; you have more nurses, more laboratory scientists, and they happen to even be the permanent staff. Seventy percent of the doctors in hospitals are not permanent staff. They are resident doctors, and that is a contract; at the end of the contract, you are flushed out of the system, so you don’t have a permanent job.

“So, the problem is not with the doctors. I agree that there are bad eggs here and there, but I can tell you that to a large extent, health practitioners are not to blame. We work according to laid-down rules. Many times, we have also been on the other side of the divide; health workers have had the cause to be on the surgical table, so we have also suffered and felt the pains.”

GOVERNMENT MUST ACT

To blame health workers alone for the rot in the system will be unfair, as government has a lot to do to bring about the desired change. The challenges the health workers face in the line of duty range from inadequate equipment, shortage of drugs, limited consulting rooms to few bed spaces.

The hospital management board also has its own role to play in bringing about improvement in the health sector, because these problems are not peculiar to any hospital; the same law governs all the hospitals in the country.

The law should be reviewed to ensure that hospitals immediately treat emergencies, and those who do not follow this procedure should be dealt with. Every life is sacred and should be preserved in the utmost way possible.

While the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends a ratio of one doctor to 200 patients, the current situation in Nigeria is that of one doctor to about 5,000 patients. There are local governments without a single doctor. The lofty ambition of the ministry of health to revitalise 1,000 primary health centres in the country by 2017 is therefore commendable. If this is done it will help to reduce the usual difficulties in accessing healthcare.

Employment of more health workers is long overdue. The main excuse is that the budget has no provision for it. Sadly, the allocation to 3.65 per cent to the health sector in the 2016 budget will maintain the status quo. Perhaps President Muhammadu Buhari would want to change that in 2017.

Also, the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), with the primary objective of making healthcare available to every Nigerian, should be made to cater to the medical needs of at least 85 percent of the populace.

Since 2006 when it was launched by former President Olusegun Obasanjo, not up to 10 percent of the population has signed up to the scheme, as a result of different bottlenecks. This should also be addressed.

The Nigerian health sector is currently in a shambles. To allow the disaster to fester may soon render redemption impossible.

3 comments

It’s not happening only in LUTH. It’s virtually happening in all government hospital,it’s even worse in UCH IBADAN.

May God save us and comes to our aid.

Its really a worrisome situation honestly.. I went to NAUTH Nnewi and after the usual lackadaisical attitude of the lady that should give me card, I got the card and was asked to go and pay at the accounts section. When I got the there, the place was under lock and key and people were there waiting and some claimed they had waited for at least an hour and there was nothing anyone could do until they paid. The worst of them all are the non medical staff. Those ones are devils in human clothing. May God help us all in this country..

Your article though probably written in good faith is wrongly titled and unfairly characterises doctors and nurses in LUTH. While i do not think for a moment that LUTH is perfect or even close, it is very discouraging to see the hard work and dedication of many of the staff there, being thrown down the drain. As a healthcare worker myself, the reality is most times we are being asked to make bricks without straw or clay! I feel the work of journalism should be to put truth in perspective. If LUTH is so bad, why are the other hospitals sending their patients there. The truth is LUTH and other tertiary govt. hospitals get the worst cases, many times delayed at home, in other hospitals and in some places not worth mentioning. When such patients come in ‘as emergencies’, the relatives now look for miracles which sometimes happen but not always. We compare our health system to other nations without regard to the staff levels or funding for resources. The truth is the staff are overworked/overwhelmed most times and what is seen as callousness is just a ‘coping’ mechanism to avoid complete collapse -mental and physical in the face of extreme challenges. I appeal that while we feel for the patients can we spare a thought as well for the people who have to face this situation everyday!