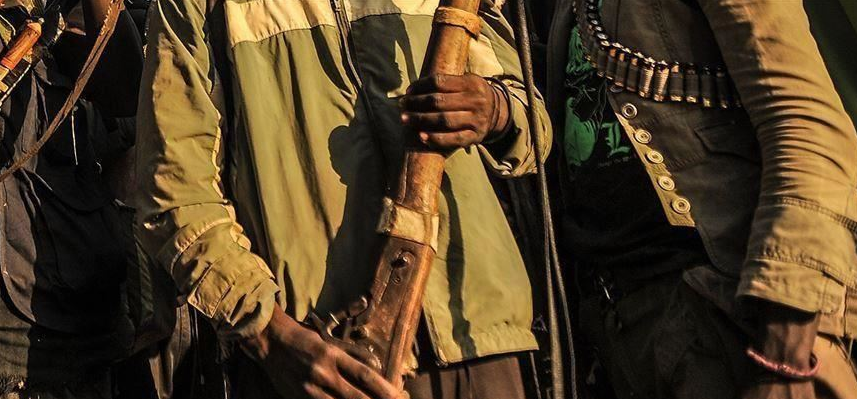

The news was grim. Over 30 insurgents from the two extremist groups, Boko Haram and the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) had been killed in a fight that lasted several hours on new year’s eve in Borno state, northeast Nigeria. That skirmish is now emblematic of the crisis in the region. The Islamists have turned the gun on one another and are engaged in a fratricidal war for supremacy. And since the groups appear evenly matched, the war is protracted with each side laying ambushes for the other and slaughtering their former brother-in-arms like chickens.

It is an interesting intersection in the Islamic insurgency crisis in Nigeria, which began around 2009 with the extra-judicial killing of Yusuf Mohammed, the leader of the Boko Haram sect. At that time, the group was known by its official name Jamā’at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da’wah wa’l-Jihād (Group of the People of Sunnah for Dawah and Jihad’) but because of its detest for western education (Boko in the Hausa Language), it soon became popular by its Boko Haram alias, which loosely translates as “western education is forbidden”.

Led by Abubakar Shekau, Yusuf’s former right-hand man and deputy, the Boko Haram sect was ferocious in the pursuit of its vision of a post-Nigerian state where the constitution will be replaced by the Sharia and every citizen will come under its firm theocratic rule. It engaged in the wholesale destruction of communities and murder of anyone that stood in its way of conquering the whole of the northeast region and thereafter, the entire Nigeria. Its enemies included state governments, the police, the armed forces, moderate Muslims, and, of course, Christians. It was such a ruthless and efficient organisation that at some point a large swathe of Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa states had been conquered by it and there was a real fear of the sect toppling the state governments.

But Shekau’s violent reign did not sit well with some of his comrade-in-arms. The main complaint was that he was too violent and did not make a distinction between Muslims and ‘unbelievers’ in the war against the Nigerian state. This led to a schism within the group, with a new faction – ISWAP – emerging, supposedly as the moderate arm. This civil war would eventually cost Shekau his life as he was killed by the ISWAP after rejecting its offer to surrender. ISWAP also killed most of the leadership of the Boko Haram group that refused to defect. Lately, however, Boko Haram appears to have resurged and the two groups are engaged in a life-and-death fight for control.

And herein lies the lesson and focus of this essay. It is impossible and futile to impose a monopolar worldview on people, whether this is religious, racial, social, or political. Humans are generally wired to be diverse and to have a multiplicity of understandings and opinions on the same subject. Consider it. Even Boko Haram, a sect that claims to be carrying out the bidding of God and seeks a theocratic utopian state cannot agree on what constitutes that vision and the strategies to bring it to fruition. Were the leadership of Boko Haram and ISWAP capable of introspection and reflection, they would come to understand and realise the futility of their campaign: That it is impossible to make everyone accept their fundamentalist interpretation of Islam.

Advertisement

So it is with other fundamentalist groups. It is just a matter of time before strains appear in them and they split into ideological factions and camps. But this rigid approach to life is not exclusive to Islamism and is reflected in many other areas too. It is in fact becoming evident in some Christian groups, especially of the Pentecostal kind, which has literalist interpretations of the bible. While these groups do not engage in violence as of yet, their fundamentalist approach has caused rifts in families, communities, and workplaces.

It is worth noting again. We all cannot agree on the same thing with the same degree of conviction. So, whether it is Islam, Christianity, or atheism (or in-between), there will never be a monotony of ideas or uniformity of beliefs. People will differ. There will always be the rebel, the innovator, and the disruptor who rejects the established convention in religion or politics and pushes the boundaries of knowledge and tolerance.

Heterogeneity is God’s original idea. The plurality of his creations attests to this. Be they humans, animals, or the material world, the diversity of life is breathtaking and cannot be fully grasped and comprehended. So why do we reject pluralism that is so natural for a unipolar world that is artificial and forceful? Why do we think we can make everyone believe the same things we do, or see only from one perspective, ours alone? These efforts have failed before and will not succeed in the future.

Advertisement

This, however, is not to advocate for a world where anything and everything goes in the name of diversity of beliefs and opinions. That world would be chaos-prone, nihilistic, and non-functional. There should be ethical boundaries, one drawn with the intent to incentivize reasonable members of society to lead full, productive, and meaningful lives. The Yoruba of southwest Nigeria appears to understand this concept well, this idea of our shared humanity. The average Yoruba community is tolerant of people of various faiths and ethnicities as far as they fit into the Yoruba worldview of “live and let live”. I wish Boko Haram and other fundamentalist groups can learn from this

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.