File photo of children in an IDP camp in the north

On August 11, 2016, Nigeria witnessed a major setback in what had been a milestone achievement for the country: the return to the list of polio-endemic countries.

In Gwoza and Jere, local government areas of Borno state, ridden by Boko Haram – one of the world’s deadliest militant groups – an outbreak of polio re-occurred. The disease paralysed two children. This incident was described as a disaster coming on the heels of the country’s celebration of its second anniversary without the wild polio virus and its first anniversary being out of the list of polio-endemic countries. In 2016, only Pakistan, Afghanistan, Laos and Nigeria -which ended the year with 5 cases- were part of that list according to Polio Global Eradication Initiative.

Polio cases in 2016

But it did not come as a surprise. On August 9, 2016, three days before the Nigerian government announced the outbreak, civil society organizations predicted a polio comeback. Community of Health and Research Initiative (CHR) and Partnership for Advocacy in Child and Family Health (PACFaH), among others, warned this fears if the government keep dallying with funds for vaccines. They also warned that donor confidence –country’s purchase of vaccines has been subsidised the last years– will dwindle. Barely 72 hours after the release of these warnings, Isaac Adewole, Nigeria’s minister of health, announced a polio outbreak. However, he attributed the outbreak to inaccessibility of the community due to insecurity.

Eight out of every ten Nigerian children are at risk of various vaccine preventable diseases.

Advertisement

Anyhow, country’s vaccination statistics are bleak. A 2016-2017 national immunisation coverage survey done by Nigeria’s National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA), revealed that 37% of children are partially vaccinated and a whooping 40% are not vaccinated at all. Only 23% of children, ages 12-23 months, have received the complete set of routine vaccines in Nigeria, a far cry from the Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP) which seeks to achieve a 90% immunisation coverage for committed countries. According to the survey, almost eight out of every ten Nigerian children are at risk of various vaccine preventable diseases.

The causes are diverse: violence, cultural hindrances, poverty, government’s inadequacies and corruption.

Violence and lack of power supply

The WHO Regional Officer for Africa, during a meeting of the Expert Review Committee on Polio Eradication and Routine Immunisation, said that 162,616 under-five children are still unreached in Borno. “Health workers find it difficult to go to areas where there is insurgency caused by Boko Haram,” Chika Offor, executive director of Vaccines Network, tells this reporter. Lawal Bakare, spokesperson of the Nigerian Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), agrees that insecurity is a reason for Nigeria’s dismal numbers of unvaccinated children. He, however, says that in the wake of the resurgence of polio, the government has increased its effort at reaching those areas plagued by insecurity and involves the military in vaccination exercises. But a source at the Borno state ministry of health, who would rather remain anonymous, says vaccinators from the ministry do not go to hard to reach areas except if they have military escorts. And this is “hard to get”.

Advertisement

Apart from insecurity, the country sometimes finds it difficult to deliver vaccines to certain regions, amid other infrastructural challenges such as poor road networks. And when the vaccines are eventually delivered there is not enough electricity supply to store the vaccines. According to the CIA World Factbook, only 45% of Nigerians have access to electricity; in a country of 190.6 million people, 95.5 million don’t have any power supply. In comparison with South Africa, only 15% of its 54.8 inhabitants are not connected to the electricity grid. “Nigeria has electricity challenges. We have infrastructure problems in the supply chain of our vaccine supply in the country,” Bakare, the NCDC spokesperson, says. Vaccines have to be stored using cold chains which are dependent on technology and infrastructure. According to NCDC, the government intends to walk its way out of this quagmire by “collaborating with some big companies… in terms of using the diverse logistics of likes of Cocacola and the power station of the likes Airtel in Nigeria where there is 24 hour power supply”.

People cultural hindrances

NCDC spokesperson talks about what he described as the “people dynamic” -where some Nigerians refuse vaccines because of misconceptions around vaccines. UNICEF’s Modibbo Kassogu, who works closely with the Nigerian government, collaborates Bakare’s stance. He harps on the misbeliefs of several Nigerian households, including that “immunisation causing infertility”. He says these views are strong believed with some caregivers refusing to vaccinate their children.

Kassogu says campaign strategies need re-assessments so they are tailored to fit the peculiarities and the nuances of communities who refuse vaccines. “We have to know our communities,” he explains. “There is a lot of work to be done”. Work that is not limited to just a mindset shift about the essence of vaccines but also about increasing awareness on the compulsory and routine vaccine schedule. For now, statistics from the NICS survey shows that 22% caregivers mistrust or fear vaccines, 11% have no faith in immunisation, 23% of caregivers think that the child is fully vaccinated, nine per cent reported they were too busy for vaccines and 18% did not have the time or had other family issues to attend to, among other reasons.

A case of poverty

Chika Offor, from Vaccines Network, says poverty is a major reason caregivers do not take their children to receive the entire one year routine vaccines. “There is no money in the country, the poor are getting poorer. […] They are torn between taking their child for immunisation or buying food. A few will choose immunisation, but most will choose food,” she tells this reporter.

Advertisement

“They are torn between taking their child for immunisation or buying food. A few will choose immunisation, but most will choose food”.

“If children are still dying from environmental, nutritional issues in the community, there will be a disconnect when you tell them that vaccines prevent deaths.” Like Hassana and Husseina, toddlers who died after their intestines got perforated, a complication arising from typhoid. The girls, darling of their community in Damagaza, died in 2016 after they came down with a terrible bout, symptomatic of high fever and stooling and got as a result of unclean water. In this slum of Abuja, the Nigeria’s federal capital territory, there is no potable water; water is fetched from streams with unclean water.

“These issues steal the success of immunisation”, laments Offor, who notes that Hassana and Husseina were fully vaccinated. “How do you tell a mother who has immunised her children and her child dies from typhoid -a water-borne disease- which by the way has vaccines that is not routinely available, to immunise her children? She simply won’t take you seriously.”

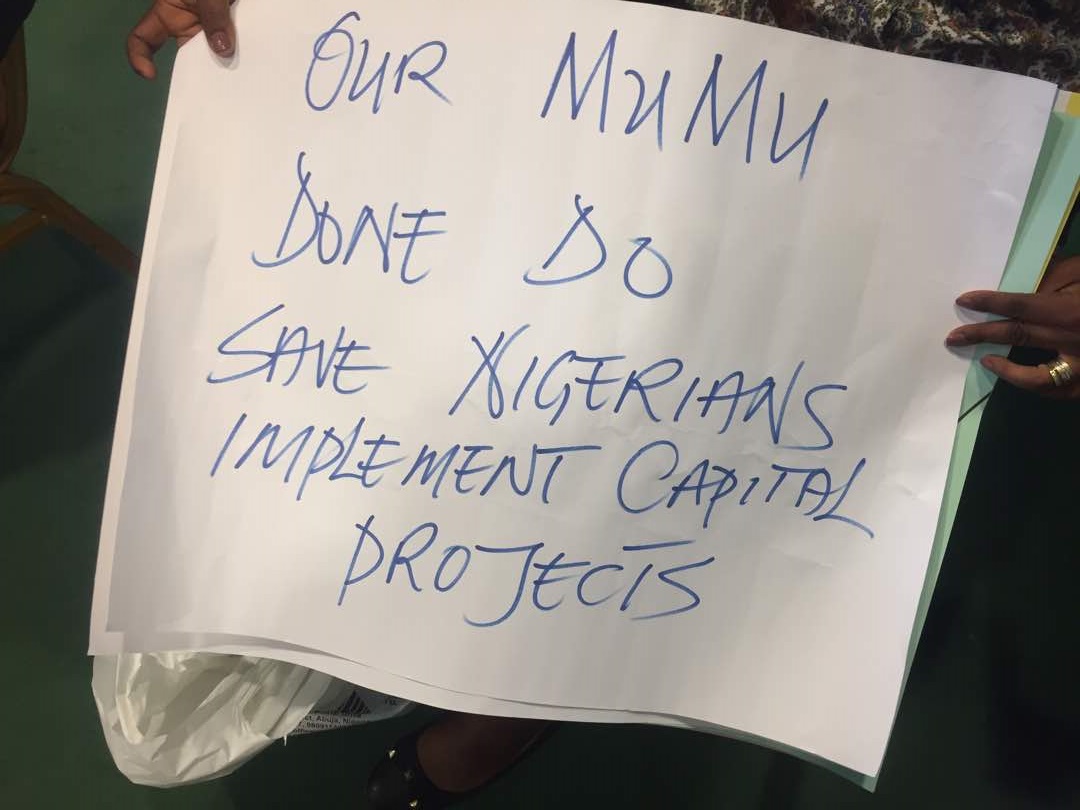

A mirror into the Nigerian government’s inadequacies

The country’s entire last budget for health is about 4% whereas the global average was 15.5% in 2014. In 2017, the country’s capital budget for health for its over 190 million citizens was 55.61 billion Nigerian naira (₦) (an equivalent of €120.4 million). Almost its fourth part, ₦12.5 billion (€29.4 million) was allocated to immunisation. In the first quarter of the year only 2% of this budget has been released, Offor says. Ministry of Health refused to clarify this point and answer our questions.

Advertisement

Aminu Magashi, coordinator of Africa Health Budget Network, says the non release of vaccine budgets is an age long problem. He calculates that Nigeria currently has a funding gap of €195.3 million for 2017-2018 vaccines procurement. “To address the funding gap, another $125 million from the World Bank was secured this year to co-finance procurement together with the support by GAVI,” (an international organization focused on vaccination) he says.

Vaccination of children aged 12 – 23 months in Nigeria

Advertisement

90% is the herd immunity for most of vaccines.

Clearly, this funding is still not enough. As Offor, also member of NIFT, puts it, the money Nigeria needs for routine immunisation is the money for the entire health budget. “The budget for vaccines is not enough. Even the one that is available is not being released”, she tells this reporter. This last October, Nigeria began its measles vaccination campaign but while the federal government had fully released its part of funding, only four (Borno, Kebbi, Imo and Nassarawa) of the 36 states in the country have paid their counterpart funding. The NPHCDA, the National Health Care Development Agency, has sternly warned all states that don’t release funding for measles vaccination by September 15 will be shut out from the campaign. While this portrays the NPHCDA as having low tolerance for the states’ government shortcoming in terms of vaccine funding, the lives of millions of children are at risk. Currently, 58% of Nigerian children have not been vaccinated against measles.

Advertisement

Corruption

The National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) is the primary responsible for vaccine coverage. This organisation has suffered a reputation dent with several allegations of misappropriation of donor funds meant for vaccination and other corrupt practices that have culminated in poor vaccine coverage.

In 2014, GAVI, in an audit of $29 million (€24,5 million) vaccine funding given to the country between 2011-2013, accused the NPHCDA of misuse of funds. The audit report described “systemic weaknesses regarding the operation of controls and procedures in national systems used to manage GAVI cash-based support”. The allegations led to the appointment of a new head of the agency, Faizal Shuaibu, who led in the elimination of Ebola when it arrived Nigeria. He is reputed to be efficient especially in terms of elimination of outbreaks. But as Bakare puts it: “the new administration will improve coverage but that would not be immediate.”

Advertisement

Another instance of corruption getting in the way of successful vaccine coverage is the construction of primary healthcare centres where routine immunisations are given. In 2015, Procurement and Private Development Centre (PPDC), a non governmental organisation, set out to monitor the 2014 procurement of NPHCDA in the areas of constructing and equipping primary healthcare centres.

PPDC, on Budeshi, an open data source platform, found that while contractors had been paid for constructing and equipping primary health care centres, there were cases of uncompleted primary healthcare centres, cases of health centres under lock and key and cases of poorly equipped centres. The organisation says the Nigerian government awarded contracts worth 2.6 billion (around 6.3 million euros) naira for the construction of 89 primary healthcare centres, but in 2017, a lot of the health centres have not been built or are poorly equipped.

For instance in Delta state, PPDC’s report showed that only five of 14 health care centres traced were active, with one of the five having no medical equipment. In Benue state, of the six centres monitored, only one was active the rest were uncompleted or not functioning. And in Kano state, only three of the six centres monitored were active, the rest could not be located, were not functioning or not completed. The neglected state of primary healthcare centres around Nigeria means for routine immunisation will suffer a setback with people having to travel far distances to acquire. “If there is no money, how can they go to receive vaccines”? Offor asked.

“Will Nigeria be ready to finance her immunisation 100% with the requirement of about 560 million dollars?”.

“Nigerian government has procured 100% of vaccines required to vaccinate our children, but the result is telling us only a few have been vaccinated. What is happening to other vaccines?” asked Yusuf Yusufari, the Nigeria Country Officer of the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation, in his speech during the NICS national dissemination meeting, while calling Nigerian government to be accountable, touched on corruption in the vaccine dissemination system. “This means that there is a lot of inefficiency in the system or a lot of inaccurate reporting, so we all need to be accountable”, he said. Looking for this accountability, all efforts to reach the NPHCDA were unsuccessful. The organisation allege staff’s strike to postpone explanations.

The country’s constant inability to meet up with vaccines funds will put the lives of millions of children in danger as GAVI gradually withdraws funding support to the country. The deadline is 2021, when the organization will stop funding for vaccines. “Will Nigeria be ready to finance her immunisation 100% with the requirement of about 560 million dollars?”, asks Ben Anyene, chairman of the National Immunisation Financing Task Team.

This investigation is a partnership with the African Network of Centers for Investigative Reporting, as part of the Medicamentalia Vaccines project.

Ekeanyanwu is a 2017 early childhood development reporting fellow

Add a comment