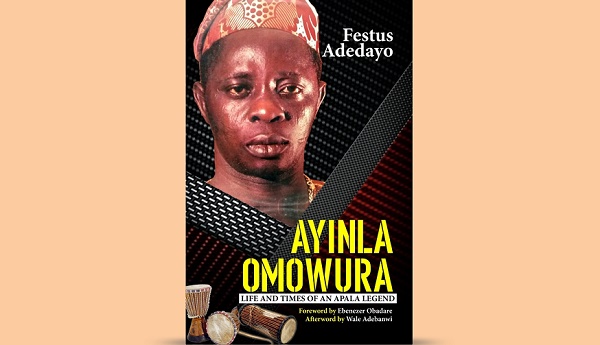

Book review: Ayinla Omowura -- life and times of an Apala legend

Author: Festus Adedayo

Publisher: Noirledge

Pages: 537

Reviewer: Dr. Gabriel. O. Apata

Advertisement

Ayinla Omowura, the renowned Apala musician died forty years ago this year and to mark the anniversary of his death, Dr. Festus Adedayo published a fitting biography of the man in Ayinla Omowura: Life and Times of an Apala Legend. Few people under the age of 40 would have heard or known about this late artiste just as few under 50 or even 60 would have heard or known of Reginald Rex Lawson. Musicians come and go and some remain enduring names through their music while others fade into relative obscurity. Dr. Adedayo’s biography of Omowura is not only an attempt to honour the memory of the man and keep his flame burning but also to celebrate his genius as one of Nigeria’s cultural icons.

I do not think such a book as this had been written about any notable musician in Nigeria, except Fela Anikulapo-Kuti. I may be wrong on this, however. The sources consulted boggle the mind and that he could unearth so many eyewitness accounts after the many decades that have passed since his death is indeed a credit to the author’s commitment to the cause. This is a labour of love, the passion of a fan and the erudition of a scholar.

The author opens by presenting a sociology of music, in which he sees music as a form of cultural expressionism. We may speak of Igbo, Hausa or Yoruba music and he contends that music serves a socio-cultural function, among others. But a note of caution must be sounded here. Music may define culture – a form of cultural expressionism – but I think music is more than that, as you find in Eduard Hanslick (1859). We may debate whether the songbird is aware it is singing or it is we who think it is singing or ascribe the art or act of singing to it — or what Kant (2000) describes as ‘purposiveness without purpose’, but something melodious is issuing out of this bird. So before we get to the sociology of music, we must look to the philosophy of music, i.e. music as a transcendental medium of aesthetic expression. So as we have highlife (1940s and 50s), Afrobeat, Juju and of course Apala, each of these styles represents a period in history, but more than that, it represents a movement and the changing tradition and styles of a people. Why this particular style and what is this style trying to say? Even if just a particular beat and rhythm, how did these styles arise and what is the message that they convey? This is a question the author answers by his exploration of Apala music, perhaps the oldest genre of Yoruba music and possibly its greatest exponent in Omowura.

Advertisement

The author traces the genealogy of Apala music: a kind of drum, a talking drum that is expressive of a musical style. The drum talks, but what is it saying? How do we decode its message? Well, we decode the message through words. But something rather interesting is going on here because music is prior to words – recall the songbird. Yoruba is a highly tonal language. The tone is transmitted into the drum and when the drum sounds certain tonal cords and we add: tolubadanbakutaniojoye – the words merely mimic the tone, which is how the tone precedes the word.

Thus, music is a combination of many elements: song or lyrics, beat, rhythm, melody and so on. This is where Omowura came into his own. His talent was not in melody, even beat or rhythm, but in song, song translated from tone. As the author points out, he was a ‘songbird’. It is song that gives meaning and shape to the inner human cry, and acts as a vehicle for the thoughts and feelings of a subject and indeed a people. The voice carries forth and expresses all the range of human emotions: the beat, like the rhythm of the heartbeat – fast, scherzo, soft, pianissimo/andante, slow largo. It is the pace that signifies the feeling. Words and tone combine to make music, to express the human condition.

As thought is to the thinker, lyric is to the poet and the music represents a movement that invites us to dance. While Fela, for example, created through Afrobeat a peculiar mixture of musical style of a post-colonial kind, Omowura returned to his precolonial cultural roots and excavated from the archives, sheets and sheets of indigenous cultural tradition of the Yoruba people. A fitting tribute to Omowura’s music is a line on page 248 of the book, rendered by one of his children, Halimat, where she points out that he, Omowura, “was an agent of cultural renaissance.” The book supports this assertion that Omowura was an interpreter as well as a purveyor of culture. He was a voice, a musical voice or ‘songbird’ in whom an entire culture appears to have been deposited and subsequently expressed. He was a lyrical poet whose renditions captured the philosophical orality (the oral tradition) of the Yoruba people and their culture. Yes, he was no doubt a philosopher who not only spoke but also thought. Wale Adebamwi makes this point in “The Writer as a Social Thinker” (2014). But here, it is the musician as a cultural thinker and exponent of the thoughts of his or her people.

The essence of Apala is the beat but the beat is nothing without the song, the lyrics or in plain simple language, the words. Words have meanings, and when strung together, they constitute a language. Language defines a people, gives them identity partly through musical expression as cultural signs. Music is therefore an important way of underscoring, as well as understanding a culture.

Advertisement

Omowura was also a historian whose body of work represents a cultural archive and memory-making as well as recrudescence and in returning to the roots of the culture preserved for us, the past now deposited in us, the living. Each time we listen to the music, we are not only reminded of a period in our lives when we first heard the music and the experiences of a time that are associated with the music, but we also connect the music to an even earlier period about which the musician sang. Thus, through the music, the present links back not only to the past but also to the future. Cultural heritage is passed down the generations like a baton in a relay race. We are living museums, since it is in us that the music lives and breathes, inside us is the cultural identity and belonging is embodied. But Omowura and indeed Dr. Adedayo represent bridges in this cultural chain, both in their different ways and media, (musician and biographer) ensuring that the chain does not break.

This is the service that Dr Adedayo has provided us with this effort. He is a torch-bearer who has taken his subject and brought it back to consciousness.

But the author has not come simply to praise Omowura. He is unflinching in confronting the dark and unpleasant side of his subject. Omowura was a man of extremes, an embodiment of contradictions. There was the quick-tempered pugnaciousness, the violence, the many scrapes with the law, the misogyny, the serial philanderer – that is if we could describe him as a philanderer, since for someone to be a philanderer, there must be someone to whom they owe certain faithfulness, as a virtue. This, however, is one virtue Omowura seemed incapable of cultivating – the casual rape he allegedly committed, the self-abuse, particularly of marijuana, the dysfunctional lifestyle that saw him father several children by numerous women: wives/concubines/

But there are other redeeming qualities like his generosity and enduring friendships. All in all, this was a seriously flawed man whose flaws cannot be excused on account of his fame or indeed a genius. Yet there is the music about which we cannot but marvel and pay homage. But then again, genius does not need to inhere in a puritanical body or in a monastery – few musicians live in monasteries, Fela married 27 wives, smoke marijuana all day yet gave the world Afrobeat. But just as we may condemn the vices of Omowura, we can also praise his genius. It is not an either/or proposition. We take the good with the bad.

Advertisement

So on that day in May 1980, Ayinla Omowura wakes up, has a bath and breakfast in readiness for the day’s business, ostensibly to take delivery of an Audi car. But there is a small matter of a motorcycle that remains at the centre of a dispute with his manager, Fatai Bayewumi. He locates him in a bar, peers through a slit in the structure and confirms that it was indeed Bayewumi. Not one to shrink from a fight, he confronts Bayewumi, holds him hostage, while waiting for the police, already summoned, to arrive. An altercation breaks out and Bayewuni grabs a beer jug with which he strikes Omowura on the head. And that was it.

Bayewumi, whose name means, lover of life, snuffs out Omowura, whose name means a golden child: all on account of a seemingly inconsequential material object such as a motorcycle. But such was the life, times and death of an Apala legend. A man whom violence dogged most of his life and died almost prophetically a violent death. Not as a warrior in battle, but as a man whose genius could not extricate him from violence, as though twined in his nature. Accounts vary as to the details of the encounter that took his life, which the author delves into in some detail. No matter. Our man is dead and Bayewumi was arrested, tried, sentenced to death for the murder of Omowura. His execution merely completed the senselessness of the act of needless violence. Both men: once friends, collaborators, manager and artiste, somehow conspired, either by design, calculation or accident to destroy each other; and this they did in a grubby shack of a beer parlour. And that was that.

Advertisement

There are little interesting titbits in the book. There are Omowura’s love of mashed beans, his lisp or inability to properly pronounce the letter ‘s’ and his smallness in stature. These little things no less bring the person to our imagination and by so doing, to life.

One of the coups of the book is that two of Nigeria’s finest minds in Professors Wale Adebamwi and Ebenezer Obadare opened and closed the book in writing the foreword and afterword.

Advertisement

The book does have its flaws. All books do. I think it is a bit too long and perhaps needed to be shortened by a third. There are quite a few repetitions and going back and forth on the same themes. The author dwells too long on Omowura’s delinquencies and violent streak a bit too much. But this may be explained by an abundance of material that the research yielded and which the author felt he had to use. This happened in a place, with corroborations supplied from too many and different sources, as though it is a legal case for which witness statements are required to substantiate factual claims.

Another example was the account of his death – whether the body was first brought home or to the hospital, etc. This is no doubt significant, but I thought the author could have swept up this controversy in a few passages as the omniscient arbiter.

Advertisement

On page 331, the author writes about the amount Omowura and his band collected at one performance, N1000 naira. It would have been helpful for the reader – a younger reader – to get a sense of today’s value of this princely sum in the 1970s – although the author does not specify what year this happened. Nothing onerous and they certainly detract only very little from the overall merit of the book. Again, the book could have done with a stronger editing input. But the strength of the book really lies in the analysis of the music itself, the many excerpts and translations that are presented in it. This is the heart of the music, the essence of the man and I suppose, the central thesis of the book.

This is also the reason that Omowura deserves this book as a tribute and I think the author has done his subject and Nigerian music lovers a great service. It is a pity that Nigerians don’t read books – few people around the world do these days – but I am also well aware of the paradox in this sentence. If you are reading this review, you are likely to read the book and so you might wonder who are the non-readers! The prose rattles on nicely. Overall, this is an impressive book that all should read, particularly those who are interested in music and culture. This reviewer has found it a pleasure indeed.

References

- Adebamwi, Wale (2014) “The Writer as a Social Thinker.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies.Vol.34, issue 4 pp.405-420

- Hanslick, Eduard (1859) The Beautiful in Music: A Contribution to the reversal of the Musical Aesthetics. London: Novello, Ewer and Co.

- Kant, Immanuel (2000) Critique of the Power of Judgement. New York: Cambridge University Press

Dr Gabriel O. Apata is a research scholar based in London.

Add a comment