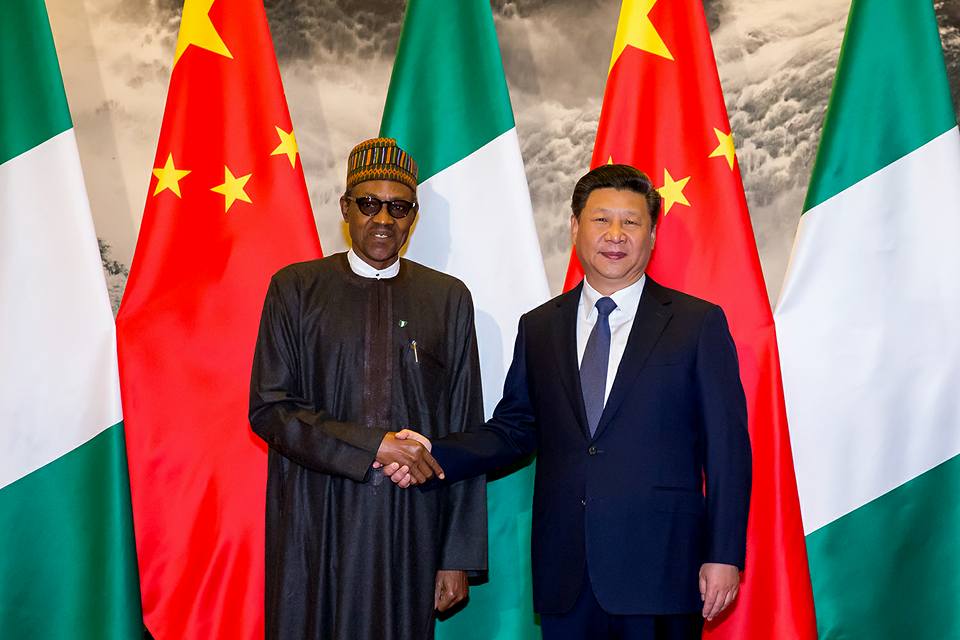

President Buhari is back from China. It is now official. No loan agreements were signed. The president facilitated critical investment agreements between Nigerian businesses and Chinese equipment manufacturers or funding agencies. The visit is over leaving us with debate about its benefits and losses. Some believe that the visit signals government’s new fascination with the eastern model of economic development.

Even if this is not true, such a visit at this time of severe economic crisis and economic rebuilding should facilitate a review of economic policymaking in the last 56 years of independence. What lessons have we learnt from the history of economic development in both the eastern and western hemispheres? If we are to turn east, we should look out for the signposts. What lessons should we be learning from China and its neighbors?

China and the rest of the East

The president visited only China in Asia. But we should remember that China is not an outlier. The economic transformation in China is similar to those in most of East Asia. Although China is sometimes rated a third world country it is by all indications a first world industrial power, perhaps second to the United States. It is the same with Japan, Korea and Taiwan. Each of these countries matter to the world because they have moved from rural, poor and agrarian economies to industrial economies. These four countries applied same set of policies with necessary contextual variations.

Advertisement

China and the East Asian countries of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan are the only uncontestable success stories of late transition from underdevelopment to development in a century. They successfully restructured their economies to ensure sustainable economic growth. The Asian economic miracle is all about these four countries. The rest of Asia countries are fanciful economic success stories. Malaysia is close to an industrial economy but still far away. It imitated the South Korean model but lacked the nerve and knowledge to go all the way. Singapore and Hong Kong are not industrial economies and their GDP growth as financial centers cannot sustain severe economic crisis as we saw in the Asian financial crisis. These four East Asian countries are the only part of the world that has witnessed successful and sustained economic development. Latin American countries, including Brazil, the site of neoliberal experiments in free market economy, are not credible economic success stories. Japan, China, South Korea and Taiwan rigorously implemented three policies which Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong and Thailand did not apply or did not rigorously and coherently apply. As Joe Studwell’s well-researched book, How Asia Works puts it, East Asian countries reformed rural agriculture to enhance land ownership and increased income for peasants; protected local infant industry and incentivized it towards efficiency through export discipline; and ultimately commandeered the financial market to facilitate household farming and industrialization. Short and simply. But far reaching and deeply controversial.

Geography is Important but Policy Choice is More Important

The success of China and the rest is not about geographic determinism. Some scholars have pointed out that Africa’s parlous economic story is because it is a malaria infested tropics. Of course, a lot can be said about the impact of environment in economic development. But the impact of environment can be superseded. The fact that no Africa countries has superseded that impact is not a proof of environmental determinism, but rather a proof that African economic policymakers have made notoriously bad choices, especially at the beginning of independence. There are not many significant geographical variations between China, South Korea and Taiwan on one hand and Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam and Hong Kong on the other hand. They share similar past of poor and rural and agrarian economies with massive social injustice in terms of land barons who excruciatingly pauperized tenants and peasants who worked on their lands. Each of them tried some form of agrarian reform. But the successful East Asian countries were the ones whose agrarian reform included redistribution of land and fiscal and policy support to ensure higher productivity and increased rural prosperity for former tenants.

Advertisement

The unsuccessful Southeast Asian countries like Thailand and Philippines pretended to execute a land reform that reinforced rural inequality and reduced farm yield. Their agrarian policy did not boost rural economy and therefore cut off the oxygen for industrialization, which is enhanced domestic consumption. Whereas, the successful East Asian countries provided credits to poor farm owners in order to stave off repossession by the land grabbers, the unsuccessful Southeast Asian countries allowed, and in some cases reinforced cultural, social and economic institutions of rural inequality. It is therefore no magic that in the East Asia we saw high economic growth resulting in lower inequality. In Southeast Asian lower economic growth produced more inequality. In Latin America, even lower economic growth produced even higher inequality. Contrast with the United States which made its transition to industrial economy in the late 19th century with sets of progressive policies by Alexander Hamilton, the Secretary of Treasure, including land purchase and distribution to poor families, that resulted in equitable economic development. The history of the United States and the successful East Asians is another proof that income equality is good for economic growth.

It is policy choice that made the difference in East Asia, not geography, and not political context. All these countries passed through hash and predatory colonialism. But those who became industrial economies were hardnosed in selecting the right economic policies that reformed rural agriculture, ruthlessly promoted industrialization and focused financial transaction towards promoting export oriented agriculture and manufacturing. Notably, they refused to create a financial market that bubbled wealth into the pockets of entrepreneurs but left manufacturing plants without access to finance. Unsuccessful Southeast Asian countries promoted few privately owned plantations in the name of agrarian reform, promoted merchandising and assembling plants instead of manufacturing plants and turned their banks into financiers of skyscrapers and shopping malls that created billionaires but impoverished the country.

Beware of Ideology Masked as Economics

China and the rest of the East Asian countries took note of ideology and avoided the pitfalls. Latin American and African countries closed their eyes to ideology and drowned in the pool of ideological waters. Economic policymaking moves in ideological circles. At each epoch, especially with major social and political upheaval, economics gets trapped in an ideology which is pushed around the world like a new religion. In the world of ideological rigidity, it seems like those who succeed are contrarians, those who act contrary to precepts of the new religion.

Advertisement

Recognizing the role of ideology in economic policymaking, in 2003, when President Obasanjo appointed the then World Bank Vice President, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the Minister of Finance, I wrote an opinion piece titled ‘Who Should Manage the Nigerian Economy”. My contention in that piece was that Nigeria needed to have a former leftist economist manage its economy. Such a person who has recognized the limits of socialism and now understands the merits of the market as a mechanism for allocation would be a better manager of the economy than a doctrinaire free marketer who is trapped in market fundamentalism. This had nothing to do with the bona fides of Dr. Okonjo-Iweala but rather a recognition of the ideological landscape of economic policymaking. I had argued in two books on privatization and the NEEDS policy how the outbreak of market fundamentalism in the form of economic neoliberalism, later to be nicknamed ‘Washington Consensus”, constrained wise economic policymaking in the third world. That is what New York opinionated columnist, Thomas Friedman, celebrated as ‘the golden straightjacket’. It is supposed to push nation towards the virtuous path of prosperity but it has pushed developing countries into deeper underdevelopment.

Multilateral financial institutions played key role in the dictatorship of no-alternatives. The World Bank’s role in economic reform in developing countries like Nigeria has been underwritten largely by the ideology of less government that took fundamentalist meanings in the Reagan-Thatcher era. During this era the cold war between capitalist west and communist east was ending in the west’s favor. Neo-liberal theorists interpreted the eventual collapse of communism as a triumph of the sets of market practices, core values and ideologies of the American Business Model (ABM) and institutions of liberal democracy and the convergence of the world to a set of best institutions that correlates with the templates of the free market economy. This hasty and tendentious interpretation foisted on development planners in the periphery South a fait accompli on the available options for development. As Hernando Desoto wistfully puts it in his classic, The Mystery of Capital, “there is one game in town”. Of course, that game is mimicking the market institutions in the prosperous west.

But, the tragedy is that the recommended menu for these developing countries often bears little resemblance to the set of policies that guided countries of the west to its prosperity or the policies they are implementing to sustain their prosperity. Cambridge University economist, Ha-Joon Chang, has assembled evidence to prove that the Now Developed Countries of the west embarked upon the opposite of the ‘free market’ policies which they prescribe for developing countries. Their periods of growth were marked by infant industry protection, expansionary public expenditure, and massive government intervention to correct market failures. But they asked those aspiring to development to do the opposite. Just as George Fredrich List, the father of economic nationalism, put it, nation that attain development through dirigisme economics turn back and remove the ladder and others to follow free market economics.

At the heart of neoliberal economics is an ideological view about the role of state. The philosopher-king of neoliberalism, Frederick Hayek, an Austrian who fled communist dictatorship with a beef against socialism, wrote a magisterial book, “Road to Serfdom” which branded government intervention in economic activities as ‘evil’ and glorified individualism. Professor Milton Friedman became cheerleader of the movement that grew out of ‘The Road to Serfdom”. Friedman’s book, Capitalism and Freedom, became the holy grail of the Chicago School that promoted the concept of the minimalist state. In Latin America, Chicago boys ran riot with a brand of ideological economics that was built on the Hayekian distrust of the government and Friedman’s theory of opportunistic intervention. Friedman has counseled his disciples to wait for the auspicious moment of social upheaval to remake the society. The Chicago boys saw that opportunity in the economic distress of the 80s when trade deficits and commodity price crash indebted developing countries to both London and Paris clubs. To address the debt crisis, neoliberals urged countries towards deflationary economics with reduced wages, removal of subsidies and liberalization of domestic and international factor and product markets and the diminution of the public sector.

Advertisement

Neoliberalism succeeded largely because it cleverly masked its ideological mission. It passed off its ideological prescriptions as natural truths. Neoliberalism deplored socialism and pretended not to be an ideology. Economists like Adelman has wondered why their colleagues did not see through the error of neoliberalism. There are obvious theoretical shortcomings in neoliberal economy yet it did not appear so apparent because it was an article of faith. Fundamentalist free marketer propagated their ideology with religious fervor. The unwitting swallowed everything. Latin American and African policymakers swallowed the ideology of ‘government is evil’ and ‘government has no business in business’. China and the rest rejected that doctrine and accept the pragmatic idea of prudent state planning forcefully championed by George Friedrich List and the German Historical School. Today, China and the rest are smiling and we are mourning.

Recognize Ideology but Manage Pragmatically

Advertisement

East Asian economies succeeded not because they wholeheartedly embraced the either the doctrine of free market or socialism. They succeeded because they avoided ideology and embraced pragmatism. China has a long history of false steps, even up to the period of Mao Zedong and the cultural revolution. The Great Leap Forward set China back, especially with the collectivization of agriculture, resulting in mass death and failed industrialization. Deng Xiaoping changed the game. He initiated a gradual, programmatic and sensible reform that started with returning the land to dispossessed peasants with guaranteed tenure to encourage irrigation, higher seedlings and extension services. Xiaoping tracked the benefit of increased productivity in agriculture into gradual industrialization. At a point he started to open China to western technology and capital, but in a controlled and strategic manner through the use of special economic zones.

Deng’s China abhorred the both rigid ideologies of communism and the laisse faire theory of neoliberalism and embraced pragmatism. This approach is exemplified by the famous saying of Deng Xiaoping that it does not matter whether my cat is red or white as long as it catches the mouse. China followed the example of Japan and South Korea where pragmatic leaders like General Park wisely implemented transformative reform of agriculture and deliberate but systematic protection and nurturing of infant industry to transition their countries to industrial economies. In these countries, pragmatic leaders enhanced efficiency not by surrendering to free trade. But they used export discipline to improve productivity. They learnt from List and his disciples that you don’t embrace international trade wholeheartedly when you are industrially underdeveloped. The secret of the success of the East Asian countries is the pragmatic insight that what will ensure industrialization is to protect and nurture infant industry through export discipline. Export promotion worked in East Asian while import substitution failed in Southeast Asia and Africa.

Advertisement

China and the rest recognized the pitfall of crony capitalism. When they raise tariff to protect infant industry they forced those industries to perform according to export benchmarks. Those who failed lost fiscal and policy support from the state. By so doing they chose winners and losses through transparent and value-adding discipline of international trade. This is a prime example of a development state; a government, as Stephen Cohen and J Bradford DeLong in their recent book, Concrete Economics: The Hamilton Approach to Economic Growth and Policy, “that signaled the direction, cleared the way, set up the path, and – when needed- provided the means”

Leadership Matters

Advertisement

The divergence between China and the successful East Asian countries on one hand and African countries on another hand may be the quality of leadership during their transitions. We can even notice the difference that leadership makes to development in the varying outcomes in the Asian continent. South Korea made it. Malaysia has not. Malaysia attempted some of the policies that South Korea, China and Japan practiced. Malaysia tried to do agricultural reform. It had ambition to be an industrial power and boosts a financial high street. Malaysia got it wrong in selecting the wrong policies and executing incompetently and halfheartedly. Unlike General Park, Malaysian Prime Minister, Mahathir, did not undertake the sort of agrarian reform that freed rural households from economic misery and improved farm yield. In the place of household farming Malaysia build one-man plantations. Most of the political elites were landlords of these plantations.

On manufacturing, Malaysia did not impose the sort of export discipline that South Korea imposed on its industrialists. The lack of export discipline encouraged cronyism and ensured that assembling plants rather than manufacturing plants thrived. Malaysia allowed politically connected persons to own banks and use them to get rich. As they say, to steal a country own a bank. These crony capitalists used the banks to finance skyscrapers and shopping malls whereas banks in South Korea were forced to finance manufacturing. The result is that few Malaysians became billionaires and the country lagged behind in industrialization whereas in South Korea, few Koreans were millionaires while their country advanced as an industrial economy.

Mahathir is a headmaster’s son whilst General Park was the son of a peasant. Mahathir admired the industrialization plans and processes in South Korea. But he lacked the focus and discipline to replicate the success story. He lost sight of the process and got caught up in anti-neoliberal rhetoric. He also got distracted by the ethnic politics of Malaysia and instead of building meritocracy he pandered too much to affirmative action for the Malays.

The pragmatism of the successful East Asian economies was a product of both the pedigree, training and temperament of the leaders who happened on the scene after their independence. These leaders, particularly those of South Korea and China were well informed about the conditions of colonialism and the ideological basis of their underdevelopment. They came from the right side of the social divide, namely the peasants (although Deng was a grandchild of a former ruler). They also were patriotic and overwhelmed with a passion for industrial takeoff of their countries. Although they were flawed men in some way, they were all undivided on the mission. They were not prisoners of narrow and sectional interests. One thing was very clear, they forged no strategic business liaison with foreign or local business class. This helped them to exercise clear-sighted and emphatic direction of economic relations. They never believed that private sector would develop their country. Rather, they believed that the public sector would develop the country using the private sector. Theirs was entrepreneurial governance, mobilizing and incentivizing for the long term transformation, not the short term profits.

You Need a Strong State

Often I hear people argue that it is the private sector that will develop Nigeria. This is a joke. The private sector has never developed a country and would not. Business men and women will continue to look for opportunities to make money. Wherever they see the opportunity they move in. This is legitimate. But, it is not the job of the private sector to create public value. The public leaders are responsible to govern the market in a manner that induces businesses to produce public value while trying to make money. This is what China and the successful East Asians did. In development, the invisible hand is not the hand of the market. It is that of the government.

As expected there have been attempt to mischaracterize East Asian success as the triumph of the free market. The World Bank played a fast one in a report that described East Asian economic miracle as a fruit of free market rather than robust economic planning. That was wistful. As Robert Wade and other made it clear, the East Asians got it right with the set of policies that did not give free rein to free market rather effectively governed the market to produce desirable outcomes. In matter of privatization, these countries were never naïve to assume that transfer of ownership to private firms would produce efficiency gains. No. they know that the private sector will be efficient if the rules and incentive structure forced them to be efficient, sometimes by inducement, sometime by strong enforcement and other times by sleight of hand.

Today, China’s great wealth is produced by a swath of public firms. This does not prove that public ownership is better than private firms. Rather it destroys the silly assumption that ownership is what matters. Clearly, what matter is how we resolve the principal-agent crisis at the heart of corporate inefficiency. In matter of industrialization export discipline and competition may be more important than type of corporate ownership.

As we count the costs and benefits of the China trip it is now time to review our industrial policy. How much are we protecting local industry? Are there potential winners that we can nurture to global competitiveness through export discipline, R&D investment and fiscal supports? From China and the successful East Asian economies we have learnt that the successful development process is a process of ‘learning by doing”. Only leaders who secure an environment for quality learning-by-doing, while adroitly managing the impact of the external environment will succeed in ushering a successful transition to industrial economy.

Dr. Amadi practices at the Intersections of Law and Economics for the management of Public Policy for Development.

6 comments

Sam Amadi i have never been your fan but always read your articles i will say this is a masterpiece.This need to be republished in all our dailies and recommended that our leaders should read read and read it.

Dear writer, there is no question of doublespeak in Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala’s opinion on the state of the economy while she was in office. She knew better, since she was the coordinating minister, so you have no authority to judge her summations.

It hurts when I see fabricated comments about Madam Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, especially when reality is glaring right in the liars’ faces. The same woman they have relentlessly condemned has continued to strive in all her endeavours. She is never moved by their lies, I salute you ma.

A woman with a clean mind and a pure heart will always be vindicated even when she is wrongfully accused. Irrespective of the circumstances, the truth will always suffice. Moreover, the facts and figures are there for reference purposes.

Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala’s name should never be linked or mentioned alongside corrupt leaders who are bent on seeing her downfall simply because despite stealing and did everything within her power to ensure the funds were used for the right reasons.

I never knew this side of Sam Amadi before. Indeed this nation is blessed with quality minds.