Agriculture and Allied Employee's Union of Nigeria (AAEUN) members march with chicken and crates of egg

BY ZUHUMNAN DAPEL

The minimum wage is the lowest legally allowed income below which no worker in salaried employment should be paid. The rate varies across cities and countries. Contrastingly, it is higher in advanced countries than in developing countries because of the differences in the costs of living. For instance, with $15, one could pay for only one haircut in the United States. Converted, this same amount will buy roughly 30 haircut services in low and middle-income countries.

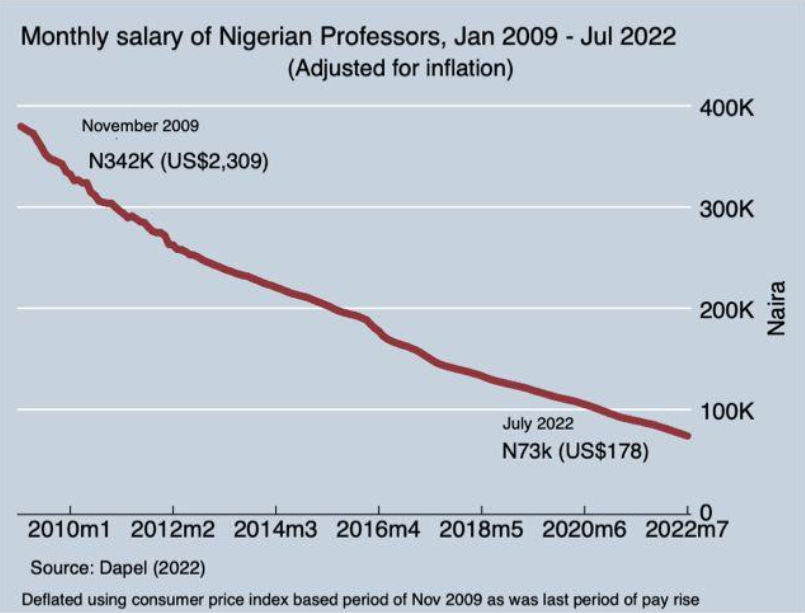

In Nigeria, the public sector monthly minimum wage was N18 (or $25) in 1970, and by 2023, it had been raised to N30,000. But even with the pay raise, the cost of living has risen faster than the minimum wage, thereby collapsing, by about half, earnings in real terms. For instance, here is a piece of evidence on inflation, boosted by currency depreciation, has been decimating the pay of Nigerian professors, eroding purchasing power from US$2,300 a month in November 2009 (the last time the pay was raised) to US$178 a month as of July 2022.

Advertisement

In other words, inflation, within 176 months, has wiped out roughly N270, (or close 80%) from the take-home pay of the highest-paid lecturers.

Had the government – being the employer – decided to fortify the income of the academics against inflation, there would have been, based on my calculations, an annual pay rise of 4.9 per cent or a monthly pump-up of approximately 0.4 per cent. Therefore, a professor will need N611,000 in 2022 to buy what N342,000 bought in 2009. In local currency, this is equivalent to a fall from N342,000 to N73,000.

Again, in 1974, when Nigeria was “on top of the world” during its first oil boom, the nominal minimum wage was 60 naira ($228) per month. Adjusted for inflation, this amount is equivalent to about N90,000 today. In short, the real wage has been falling and is now about 80 per cent less than in 1974. The purchasing power is now three times weaker than that of 1981, meaning Nigerian minimum wage workers are worse off now than in 1981.

Advertisement

If the government wishes to raise the welfare level of the workers back to what it was in 1981, the minimum wage should be raised to N54,000 ($149) per month. While that raise — which will substantially be financed from federal oil proceeds — is a good idea given its significant decline over the decades, the issue of “ghost workers”— “fraudsters creating fake identities to file benefits claims”— means that much of that money could likely be lost/stolen. For instance, the system that purges the payroll of ghost workers saved the government about N285 billion (more than $278 million) in 2017 and 2018 alone. This gives us an idea of how much was scooped away before the installation and use of the World Bank-supported integrated payment system.

So, how should the government respond? Policy recommendations

To allow for an effective pay raise for government workers while also circumventing, and perhaps eliminating ghost workers, I recommend the following.

First, the government should adopt a central payment system—based in the federal capital and run by the national government—to pay the state and locally salaried staff directly. This strategy would purge the system of “ghost workers”. In fact, in 2015, a similar scheme introduced by the former finance minister of Nigeria, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, weeded out over 65,000 ghost workers, saving the government over $1.1 billion in fraudulent payroll costs.

Advertisement

The central government should deduct the wage bill of each state from the state’s monthly federal subvention and then use it in paying, directly, government employees working at the state and local levels of government. I believe this will stop states from owning workers and will also help in purging the payment system – but not 100% – of ghost workers.

The government should utilise new technology to better track payments to employees. According to CGD – Center for Global Development Senior Fellow Alan Gelb, biometric identification technology can aid in this goal. In this strategy, by using biometrics, the central government can store, in a federally centralised database, the identity (e.g., fingerprints and other essential details) of government employees at all levels—federal, state, and local. Then, procure an ATM-like device (maybe through an MoU with one of the technologically advanced countries) with a built-in fingerprint feature that links (or synchronises) with the central database. At the end of every month, when salaries are due, the staff use their fingerprints to claim their salaries and other benefits, with the option of transferring part of or the entirety into their existing bank accounts.

Notably, this idea is a bit controversial. Many states will argue in rejecting this idea on the prime ground that they are supposed to be autonomous and should therefore be allowed absolute control over their finances.

Notwithstanding, proponents argue that, since states are not utterly financially independent of the central government, this strategy is appropriate. Indeed, data from Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics show that only Lagos state, the country’s commercial nerve centre, derives less than 10 per cent of its total revenues from the federation account. Federal revenue allocations to some northern and non-oil-producing states account for over 70 percent of their total revenues.

Advertisement

Finally, corruption at the state level can be minimised through some constitutional amendments: the tenure of state governors should be reduced to a single term of five years. And that former governors should not be eligible to run for national assembly (parliamentary or congressional) seats, e.g., the Senate. Why?

State governors have so many fiscal powers. They oversee internally generated revenues and state federal allocations. What then is the connection between these, and the term limit being proposed? The cost of running a campaign in Nigeria is very high and if a sitting governor is allowed to run for office more than once, he may use his executive privilege to pilfer the resources of his state and use it to finance future campaigns to tighten his grip on power.

Advertisement

It seems apparent that if the state governors want to “cement” the path to looting their states and at the same time be shielded from the wrath of the law, they start by cosying up and showing unflinching loyalty to the sitting president of the country given that the leading anti-graft agency that investigates and prosecutes financial crimes in the country, the EFCC, is under the whims of the presidency. Next, they approve succulent pay packages for their state houses of assembly members and by so doing they tend to mute the avenues that could hold them to account and by default, are granted the carte blanche to do as they wish with the state finances – pulling the switches and moving levers of both political and economic powers.

Please note, when politicians across party lines seem to ‘get along’, it’s the governed, the people that usually suffer the spill-over effect. And, when the politicians don’t get along, the people get to know the truth about what goes on in the government and therefore the people may suffer less than they would have had the politicians get along. This is a reminder of how power tussle promotes and yet undermines economic progress in a democratic setting.

Advertisement

Cutting term limits will certainly not root out or bring an end to corruption, but it may blunt the incentive of serving politicians to ambitiously loot the treasuries of their states. This proposal is not out of the realm of possibility. It is achievable if powered by political will. But the “will” seems to be a scarce political capital in a country that is in desperate need of radical reforms.

Zuhumnan Dapel can be reached via [email protected]

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment