Students coming out of a bushy, abandoned building used as exam hall IMSU

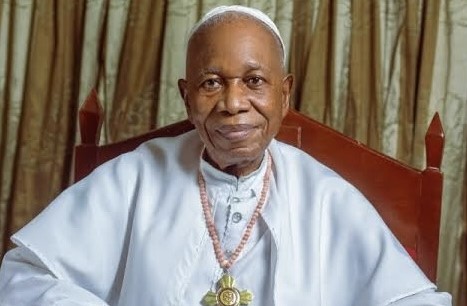

Bolaji Abdullahi, former minister for youth development and sports, has put forward solutions for the perennial strikes, unsettling funding crisis, and issues bedevilling public universities in Nigeria.

The former minister proffered solutions in a paper for Agora, an Abuja–based policy think tank.

Abdullahi said the public university system holds up to 94 percent of the undergraduates in the country and should be integral to the government’s vision of economic growth and long-term human capital development.

In the 12-page publication, Abdullahi discussed how Nigeria can reposition its public universities for national growth and global competitiveness.

Advertisement

Nigeria’s public universities have seen repeated disruptions over the years due to striking lecturers protesting multiple grievances including funding deficits, poor conditions of service, and infrastructural decay.

Academic staff in public universities embarked on their 16th strike in 23 years that lasted for eight months in 2022.

Abdullahi argued that only 25 percent of university applicants are able to secure admission. He said this has forced the government to expand access by licensing the privates and setting up more public varsities in a move that undermines quality.

Advertisement

The former minister suggested a system-wide reform that addresses the elements of governance, funding, and quality assurance in Nigeria’s public university system.

Financial autonomy for public varsities

The National Universities Commission (NUC) regulates university programmes in Nigeria, what funding these programmes get, how varsities generate such funds, staffing, and service conditions of lecturers.

Abdullahi argued that excessive government interference constitutes a major impediment to innovation and creativity across these universities in ways that also affect their financing and the incentive to stay competitive.

Advertisement

Granting freedom to varsities in negotiating contract terms with their staff based on their unique capabilities and local conditions, the former minister said, will end the factor of collective bargaining that makes staff unions a disruptive force.

This, he added, will also allow each university to develop at its own pace, bring stability to the system, ensure that the lecturers are equitably remunerated, and enable the government to focus more on its quality assurance functions.

The current system of financial governance, he said, fails to incentivise competitiveness and creativity because it pays lecturers of different quality outputs the same salary only because they fall within the same scale.

For all this to happen, Abdullahi said the NUC must be repurposed for coordinating and monitoring functions.

Advertisement

Rejigging the current funding model

In Nigeria, the government is the main funder of public varsities, yet Abdullahi noted that state intervention only yields about 44 to 60 percent of what is required to effectively run a standard university, leaving a deficit of 40 to 56 percent.

Advertisement

Making an analogy with budgetary allocation for federal universities, the former minister said ₦29.36 billion was allocated to the University of Nigeria Nsukka (UNN) and 86.15 percent of this money ultimately went to personnel costs.

This, he said, implies that what has become the primary funding source for public universities only exists to pay salaries, relegating the core needs of the students for their programmes and other overhead costs.

Advertisement

Similar situations amounted to 85.8 percent for Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), 95.89 percent for the University of Maiduguri (UNIMAID), and 91.31 percent for the University of Abuja, where the bulk of budgetary allocations only pay salaries.

Abdullahi said much of the federal allocations intended to subsidise university education for the masses are left for the operational costs and the provision and maintenance of infrastructure for teaching, learning, and research.

Advertisement

One solution to this, he said, is to target the subsidy to revolve around student enrolment, not varsity administration.

“What this does is place the students at the center of the university planning, with all other expenditures, including personnel, overheads, and physical development, now revolving around the students and their needs,” he added.

The former minister said the parameter for the allocation of funding should be output, not the current input-based approach.

Explore alternative funding sources

The Tertiary Education Fund (TETFund) was established in 2011 to disburse, manage, and monitor education tax for government-owned tertiary institutions in Nigeria, including state-owned and federal universities.

The scheme, funded by a two percent education tax paid from the assessable profit of companies in Nigeria, provides supplementary support to public universities in the country to address gaps in infrastructure, training, and research.

But Abdullahi said the fund has become the only source of funding available to the varsities to carry out those activities.

He argued that TETFund follows no clear objective parameters beyond its own discretion, lobbying, and proposals.

He said a new framework for tertiary education funding needs to be developed to set such parameters that fund universities based on verified outputs in the areas of teaching, research, and community service.

As for the universities, Abdullahi said alternative funding sources must be sought out in endowment funds, while intra-university work-study arrangements should be created to help indigent students self-fund their programmes.

He added that the state should create an education bank that guarantees student loans and strengthens scholarship schemes.

Adopting cost-reflective tuition

Public varsities like the University of Lagos and the University of Ibadan only bill ₦55,500 and ₦36,800 respectively.

Private and mostly cost-reflective institutions like Covenant University have students pay ₦937,500 per session.

Abdullahi, in the interest of quality, said the current tuition-free orientation of the Nigerian government is a fallacy.

“The government has continued to give the impression that [high-quality education that is free] is possible to achieve. This has resulted in a lose-lose situation for everyone involved,” the former minister wrote.

He analysed how much is really adequate to run a university and argued that the current tuition-free orientation of charging next to nothing in public universities comes at a loss to students who lose out on acquiring real skills.

“American University of Nigeria in Yola actually calculates its fees per credit units offered by the student,” he wrote.

“It’s difficult to understand how the University of Ibadan can reasonably charge a maximum fee of N36,800 in a session for a course that AUN, Yola charges more than twice the same amount to teach a single credit.”

The former minister said Nigeria must determine what is required to deliver education to each student in a varsity, do a realistic costing, pay the universities accordingly, or arrive at a cost-sharing arrangement where the government pays more.

Private sector-oriented quality assurance

Abdullahi insisted that the state must re-invigorate the education quality assurance system and orient it towards the needs of the private sector, the job market, and Nigeria’s long-term human capital development priorities.

He said a semi-autonomous National Higher Education Quality Assurance Agency (NHEQAA) needs to be created to monitor the quality of teaching and research in the universities.

This, he said, must be evaluated in terms of their responsiveness to Nigeria’s manpower requirement and economic development plan.

“Transforming public universities in Nigeria will not be a job for the minister or the Ministry of Education alone,” the former minister said.

“The Ministry of National Planning, the Ministry of Labour and Productivity, and the Organised Private Sector (OPS) must work closely together.

“But the process has to be led by the president of the country or someone who has his convening authority to drive the process.”

Add a comment