“I left the camp since morning. We (children) went to pluck cashew nuts from the bush. We roast and eat it because there is no other food. I go every day.”

Those were the words of Mary Nuhu, 14, living in an internally displaced persons (IDP) camp at Durumi, Area 1, Abuja, Nigeria’s federal capital territory (FCT). This camp is located within the city centre of the nation’s capital with 2,830 persons in it.

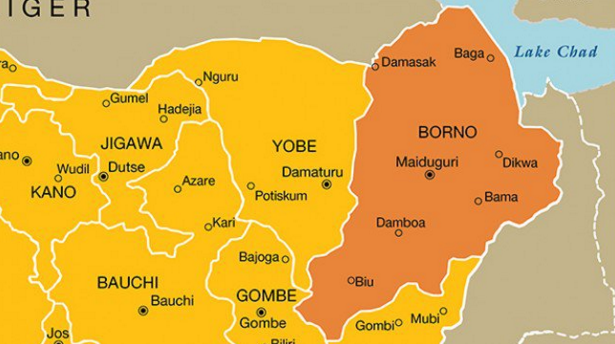

Nuhu and other residents were displaced in 2014 from Bama and Gwoza local government areas in the northeastern state of Borno. They have now found solace in Abuja and gotten approval from the Nigerian government to settle in the community.

On this sunny Saturday morning, when OrderPaperNG visited the camp, Nuhu and other children had gone to the bush.

Advertisement

The premises house a clinic, store and more than 30 makeshift apartments positioned strategically at the corners of the camp. Some men, women, and children sat at one side in clusters having a conversation and peeling off ‘dawadawa’, an African locust fruit, from the pod.

“Some of us go to the bush to get locust beans. The yellow part we eat it and sell the dawadawa part. When our children are really hungry and have cried for a while, they settle to eat this and drink water,” the chairman of the camp, Ibrahim Ahmed, told OrderPaperNG.

In order to feed this period, the minors are left with no option than to perform odd chores to survive the hunger fuelled by the lockdown directive by the federal government to contain the spread of coronavirus.

Advertisement

At 1:16 pm, Mary and the other kids in their hundreds, returned to the camp, giggling and laughing.

She was able to pluck a 150cl bottle full of cashew nuts after spending over five hours in the bush. Clutching the bottle as though she had just been awarded a trophy, she said she could not wait to show her family of seven, the proceeds of her fruitful venture.

The public relations officer (PRO) of the camp, who gave his name as Umar Ali, said women and children are the primary focus in the camp when members of the executive share resources from their private allowances or donations from well-meaning donors.

Advertisement

“Both women and children enter the bush to get cashew. If there are items in the store, the chairman will share to the children because they are the ones who suffer the most. It is not easy. This coronavirus is ‘hunger-virus’,” he said.

“Sometimes we (excos) remove money from our pockets to buy food for the children. Now, we don’t have much money again to take care of them because of the lockdown. It is supposed to be the federal government that should take up this responsibility.

“The first project of the federal government should be IDPs because they do not have any source of income, only through donations from people.”

VULNERABLE AND FORGOTTEN…

The announcement of the lockdown caused intense apprehension in Durumi camp due to their daily fight for survival. The restriction of movement has brought untold hardship in the camp as most of the residents largely rely on income from their daily hustle.

Advertisement

There was respite when the National Commission for Refugees, Migrants and Internally Displaced Persons (NCFRMI) reached out to the secretary of the camp requesting their bank details. But three weeks have gone and the IDPs are yet to receive palliatives from the federal government.

“The government did not check on our people or bring anything. The refugees commission promised to bring something but they have not done that for close to three weeks. Even the bank details we collected, the commission has not come to collect it,” Ahmed, the chairman, added.

Advertisement

“If you go to different IDP camps, it is the same situation. Others living around us who are not displaced – Igbos, Gbagyi, Calabar – they came here after hearing that the government will bring food for us but we told them we have not received anything.”

THE ‘HUNGER VIRUS’ THAT KILLED TWO…

Advertisement

Residents of the camps were sensitised about the effects and the need to follow safety guidelines to prevent the spread of coronavirus by media stations that earlier visited the camp.

As a means to prevent the virus from getting to the camp, the chairman advised that they remain around or within the premises.

Advertisement

While they had so far complied, the rules were temporarily suspended on April 15, when they were alerted that a food truck on the expressway of Apo, an area close to the camp, was distributing food items.

Two brothers, Umar and Ibrahim, who were bike riders, dashed off to the scene and were fortunate to get a bag of rice despite the stampede.

On their way back to the camp, the duo sighted the police and tried to make a u-turn to avoid being caught but got hit by an oncoming jeep. One of the brothers was preparing for his wedding before the sad incident occurred.

“It was people who were equally looking for food that saw their bodies, identified them and traced them to our camp. Then, the road safety officials brought their corpses to us. No government official has condoled with us over their death,” Ali recounted in dismay.

‘Hunger-virus’ is not the only threat to their livelihood but how to practise social distancing in a tightly contained environment which serves as an avenue for the virus to thrive. They are worried.

“It is God saving us here. If coronavirus gets here, it will kill our poor families. Allah! If it enters our camp, many people will die. I swear. We warn our people not to go to town to look for food so they won’t bring the virus to the camp,” Ahmed said.

ARRIVAL OF SAVIOURS

Since the palliatives from the federal government stopped in July 2019, aid from religious institutions and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have helped to mitigate the effects of poverty in the camp. But the lockdown has impeded these efforts.

Then, ‘saviours’ from a private company appeared and made it their responsibility to bring lunch to the camp daily for all the children and some women.

This day of visiting the camp was no exception as two vehicles from the organisation entered the premises of the camp at 2:05 pm to dish out food.

The donor taught the minors social distancing, made them wash their hands before collecting a plate of beans.

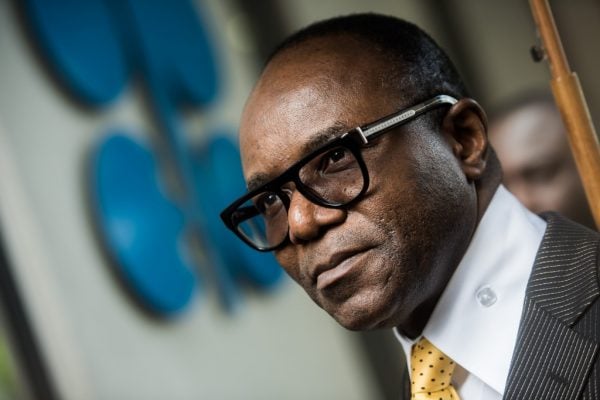

Kingsley Obokhare, chief executive officer of the organisation, said he was prompted to support when it occurred to him that displaced persons will be one of the worst-hit due to the restriction of movement.

“When the lockdown started, it was so clear that we had to stock our homes with food following the directives from the government. Then I thought, (IDPs) do not have the money or the means to stock up. We then decided to put something together and started coming to the camp. We had collaborations with a club, corporate kickers and some well-meaning Nigerians. This is the 19th day of coming here,” he said.

Obokhare stays in Mararaba, a town in Nasarawa state, and drives through several checkpoints to put a smile on the children’s faces.

“I don’t stay in town. I stay in Mararaba. Do you know the checkpoints to pass before I get here? It is killing! But I know a child is going to be happy when I come to town. It is painful to know that no money has been issued. There was a time when we came late and it was scorching,” he added.

“They saw us and screamed in excitement. In other countries, they are giving these things free. We give a meal of N500 per child. If this medium can help us, we can do more for the women.”

This story first appeared on OrderPaper

Add a comment