Opeyemi Adeyemi works with one of the big finance companies in Nigeria. He had a pay cut due to the lockdown during the coronavirus pandemic. “To keep your job during this period, a pay cut is a relief, as thousands were fired,” says Adeyemi, a 42-year-old finance expert who lives in Obalende, Lagos.

“I was overwhelmed with the prices of foodstuffs. I often discussed with my wife, who was nursing our second child, ensuring we find a substitute for afternoon meals by taking garri or noodles instead of a three-square meal in a day.”

“The cost was high on me and my household. My salary was slashed by 30% to sustain my job, then, rising inflation took a toll on me. I lost most of my savings to cater to the family.

“The cost of electricity also skyrocketed during this period and I had to work from home. Despite paying a higher electricity bill, most times I still have to get fuel to power my generator, due to the erratic power supply in my area during this period,” a visibly angry Adeyemi let out his frustrations.”

Advertisement

Adeyemi’s story is that of millions of Nigerians who lost considerable regular income due to the loss of a job or drastic cuts in salaries and wages, especially during the COVID-19 lockdown period.

The ordeal of his lower-income chasing higher food costs corresponds with many people’s responses during Dataphyte’s market survey.

The research team had set out to investigate how the coronavirus pandemic impacted food prices in Nigeria, the country reputed to be Africa’s biggest economy.

Advertisement

COVID-19: The Nigerian Experience

Nigeria recorded its first case of the virus on February 27, 2020, in Lagos. Afterward, the virus spread across the country and led to many deaths. In all, Nigeria has recorded 166,560 cases of infections losing 2,099 of them to death as at June 2, 2021.

To curtail the spread of the virus, measures recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO) were adopted. However, the continuous spread led to an ultimate shutdown of the global economy in April 2020.

The lockdown affected all economic activities in Nigeria, and indeed globally, as many countries devised measures to cope with the debilitating effects of the infections. The effect of the lockdown was felt heavily across key economic sectors in Nigeria as only essential service providers were exempted from the movement restrictions.

The full outbreak of the coronavirus in 2020 changed the normal working of the Nigerian economy. It affected many lives and livelihoods, with many families and individuals struggling to adjust and cope with its effects.

Advertisement

One of the major activities affected in Nigeria was agriculture, seeing as the lockdown was put in place during the planting season. Though it was relaxed a little to enable farmers to cultivate their crops, they were faced with difficulties in accessing farm inputs and transporting the same across the markets.

The false resilience of Nigeria’s agricultural sector during the COVID-19 pandemic

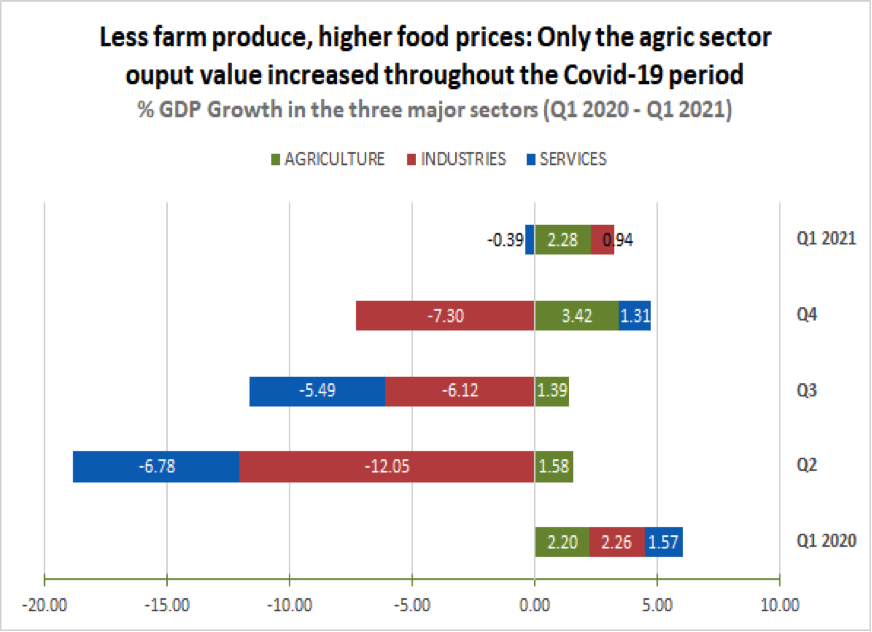

Official data of Nigeria’s gross domestic product between the first quarter of 2020 and March 2021 when Dataphyte conducted a market survey showed that the impact of the contagion was more severe on Nigeria’s industrial sector than the others. The sector had the steepest decline in output and the slowest recovery from the dip in its output.

Advertisement

The next hit sector was the services sector. However, the agricultural sector alone remained resilient, recording consistent growth in the money value of its output throughout the turbulent period, or so it appears.

While the money value of the output (gross domestic product) from the major sectors of Nigeria’s economy declined at various periods during the pandemic, only the agricultural sector experienced growth throughout the subsequent quarters of 2020 till the first quarter of 2021.

Advertisement

Analysts at Dataphyte attribute the resilience of the agric sector alone during the pandemic, unlike the other sectors, to either of two things. The first is that the level of agric production increased even during a time of turbulence in public health as the COVID-19 presented, so that more agric products were sold, yielding greater income to those in the agric value chain.

The other possibility, they posit, is that there was no increase in agric production, and possibly, even a lesser agric production, which created scarcity. The higher income from the agric sector activities then could be attributed to the sales of farm produce at exorbitant prices. The responses of food buyers and sellers interviewed during the Dataphyte survey validated the second proposition.

Advertisement

The COVID-19 lockdown restricted the movement and transportation of goods, especially food items, across the country. A ban on inter-state movement and farmers’ inability to cultivate their farmland, amongst other processes, posed a challenge to food security in the country.

Advertisement

These unusual distortions of farming activities and agricultural business shrunk the supply of various farm produce, with an attendant increase in prices of food items.

Dataphyte’s market survey showed that the prices of some food items doubled

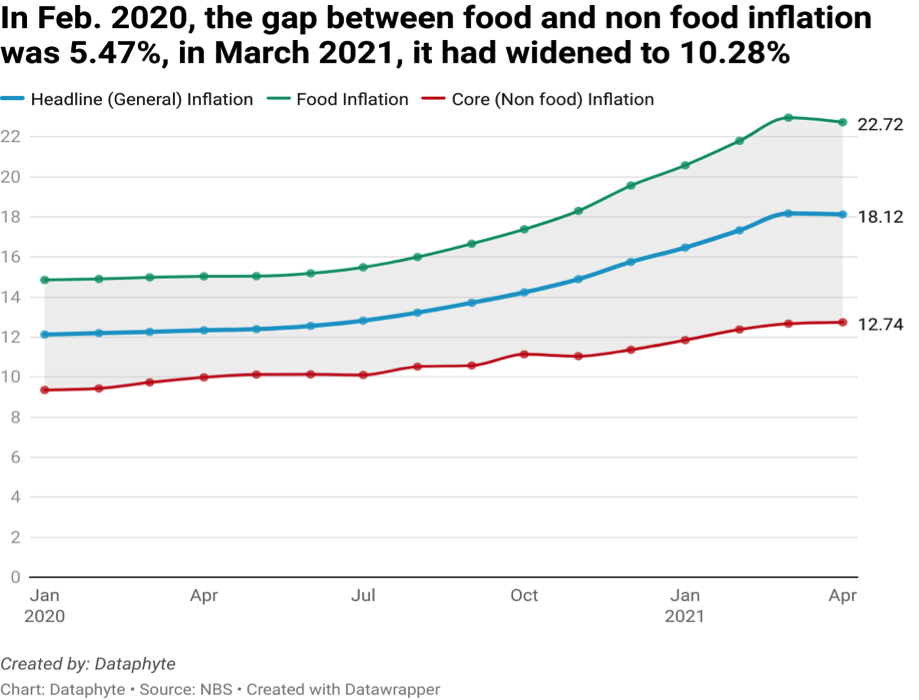

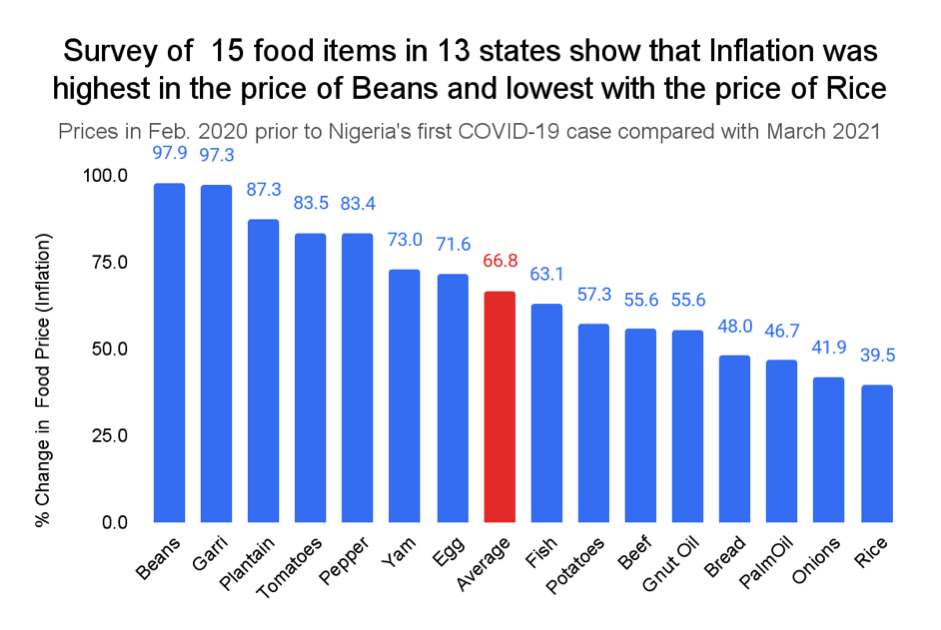

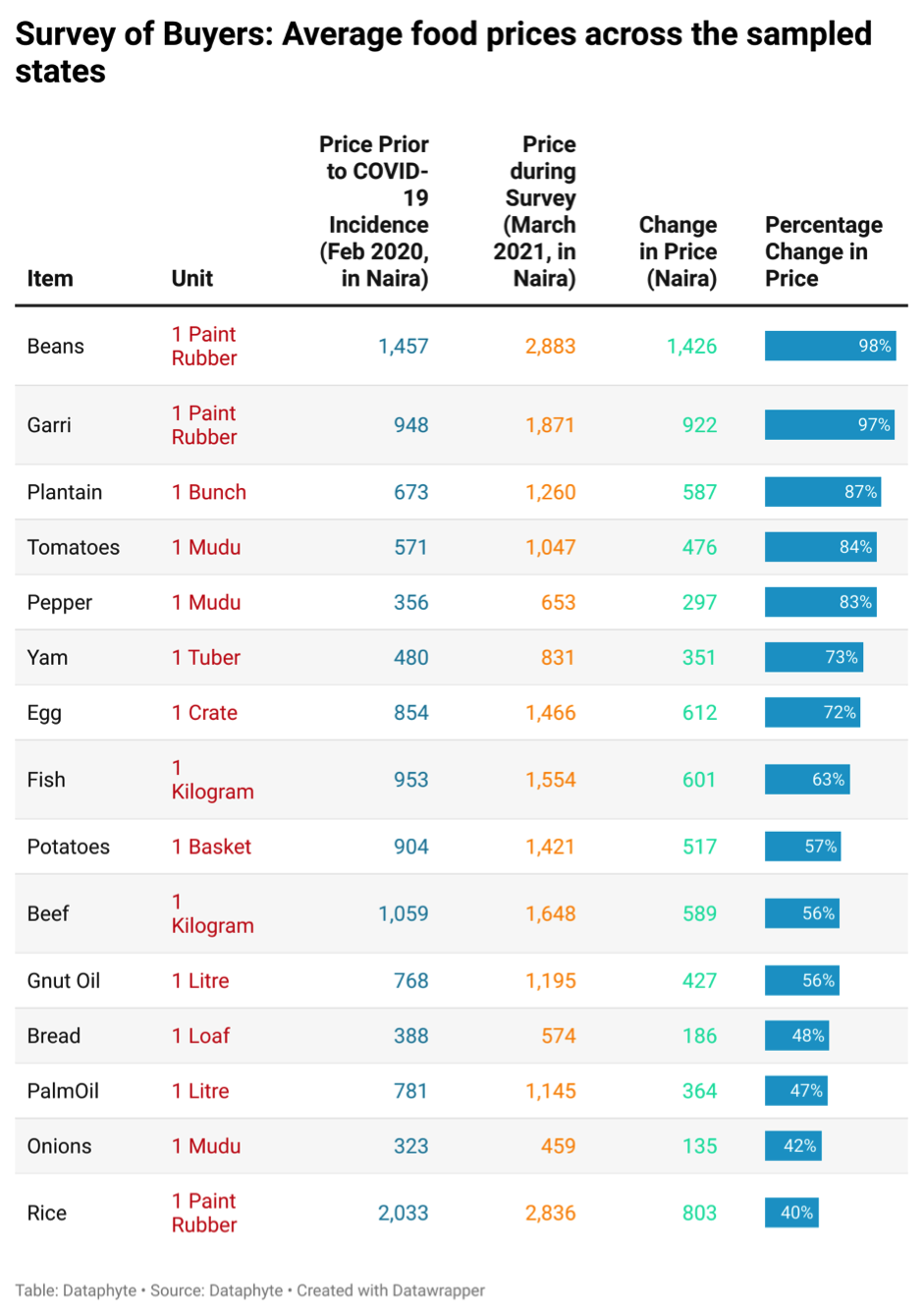

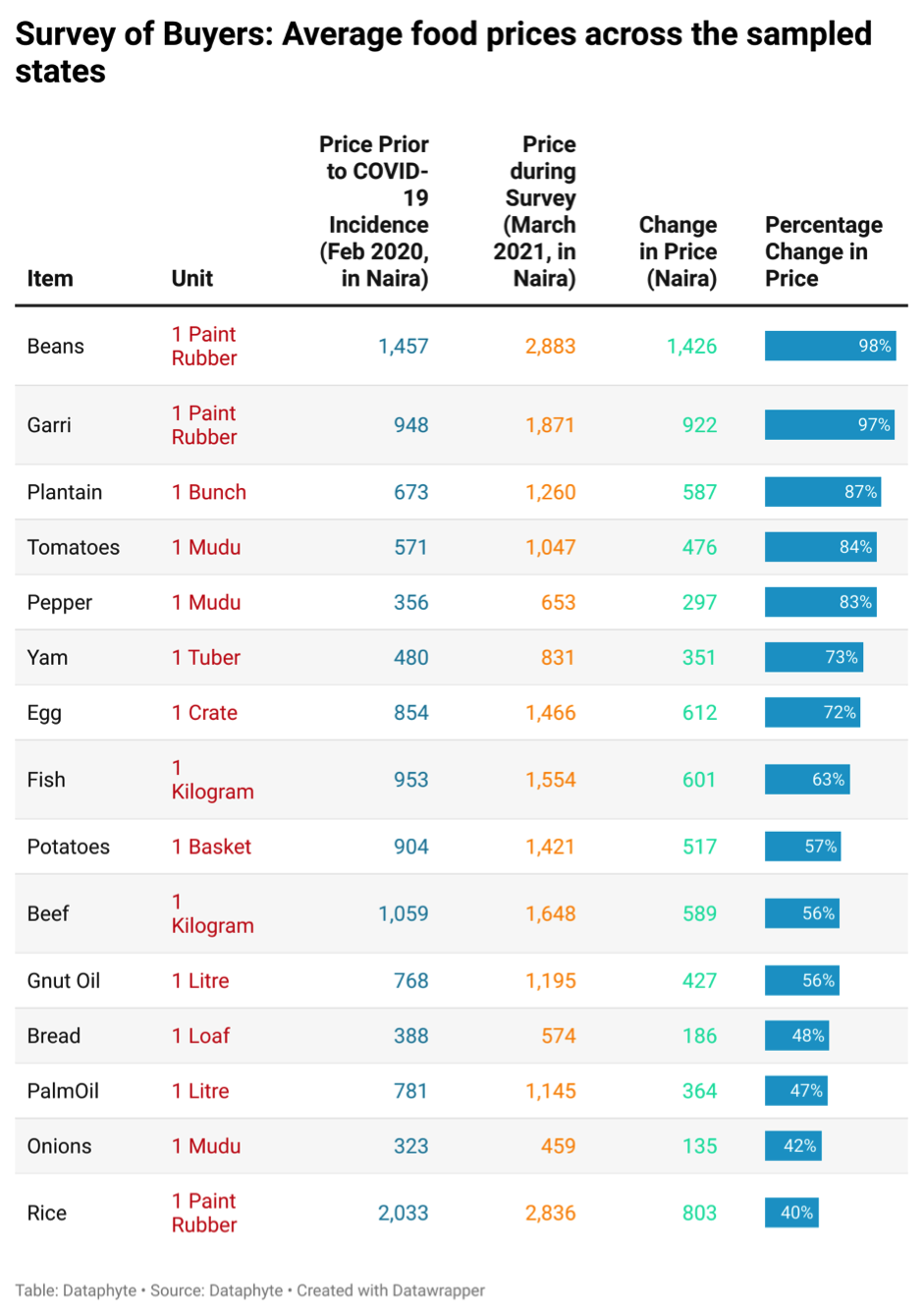

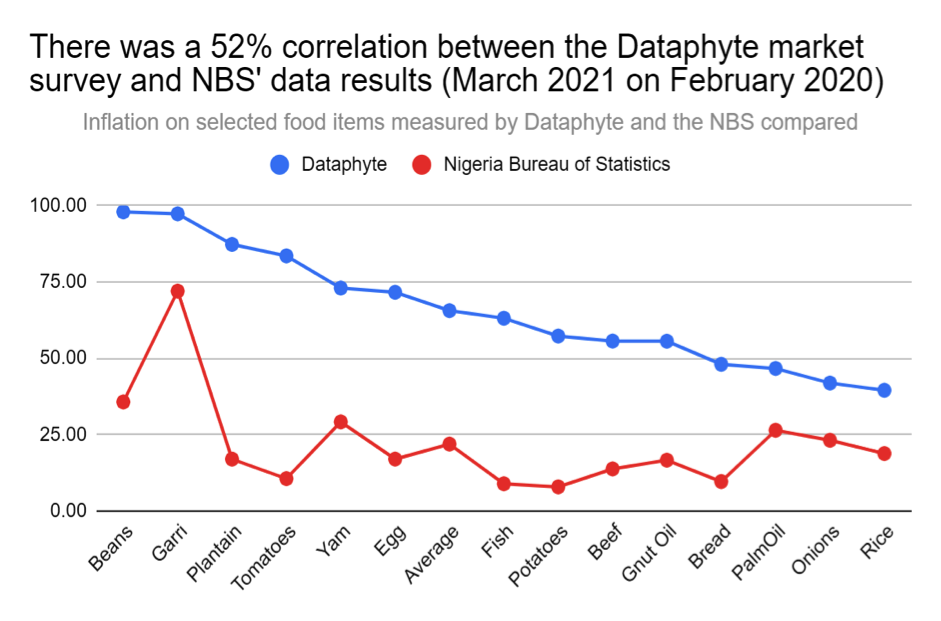

According to the recently conducted Dataphyte food price survey, Nigerians witnessed an average of 66.8% increase in the prices of food items between last year February, the month the first case of coronavirus was confirmed, and this March, when the survey was conducted.

Source: Dataphyte market survey

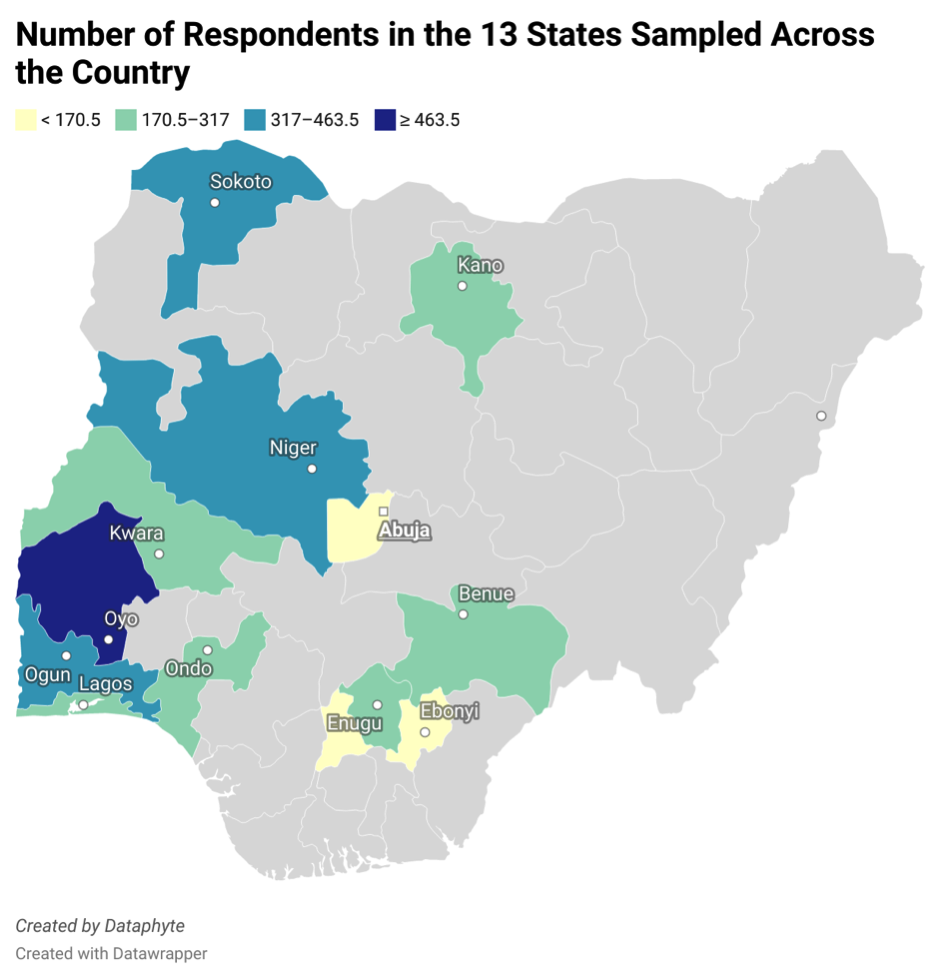

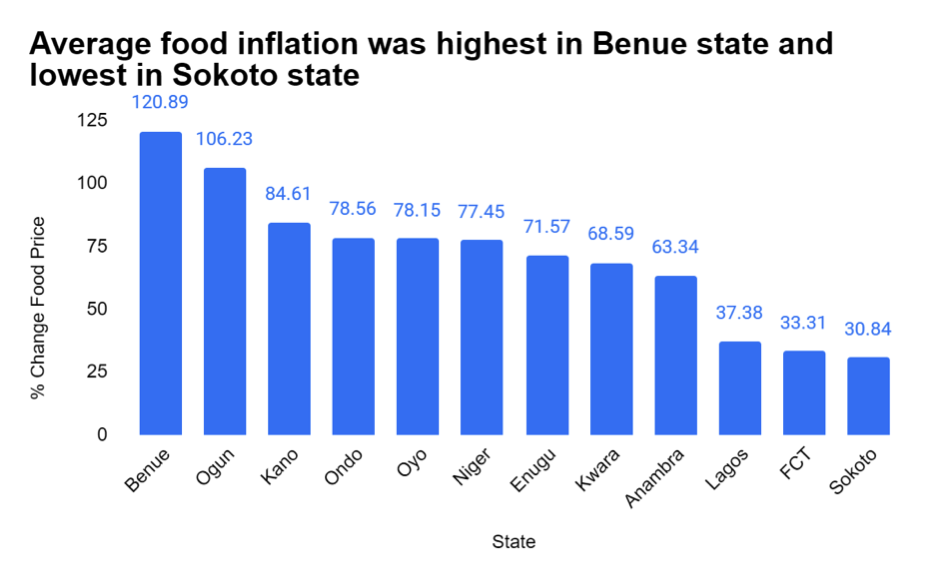

Dataphyte’s analysis of the prices of foodstuffs across 13 states in the country – one of the most extensive market surveys in the country – showed that the food price situation had contracted the purchasing power of citizens. The states sampled are Anambra, Benue, Enugu, Ebonyi, FCT, Kano, Kwara, Lagos, Niger, Ogun, Ondo, Oyo, and Sokoto states.

Map of the 13 states of Dataphyte’s research

The survey captured most staple food items in every Nigerian home, including rice, beans, egg, garri, plantain, yam, beef, palm oil, fish, pepper, tomatoes, onions, bread, and groundnut oil.

Due to the increasing incidents of attacks and high risks of violent deaths in the north-east and several north-west states of the country, Dataphyte’s field researchers were deployed to the relatively safer states.

Thus, the responses and results would reflect the food price changes and citizen experience in the researched states more than the entire country. “However, future field research that includes the troubled states is currently being considered by the Dataphyte team,” Charles Mba, programme lead at Dataphyte assured.

The price of beans and garri nearly doubled within the period under review. Beans rose from N1,457 to N2,883 per paint rubber, representing a 98 percent (97.92%) increase. The cost of garri rose from N869 to N1,856 per paint rubber, a 97 percent (97.27%) change. The price increases of these two staple foods were the highest in the last one year period of the coronavirus pandemic.

Garri is made from cassava, a tuber plant, which is one of the most important food crops in West Africa. Nigeria produces about 250,000 tonnes of it annually. Nigeria is also regarded as the largest producer of cassava in the world. Garri is either made into ‘eba’ or soaked to drink as flakes. It is often regarded as the ‘poor man’s food’ because of its relatively low price and the ease of taking it as a snack without the need of cooking, unlike most of the other food items.

How much of the increase in food prices can be attributed to COVID-19?

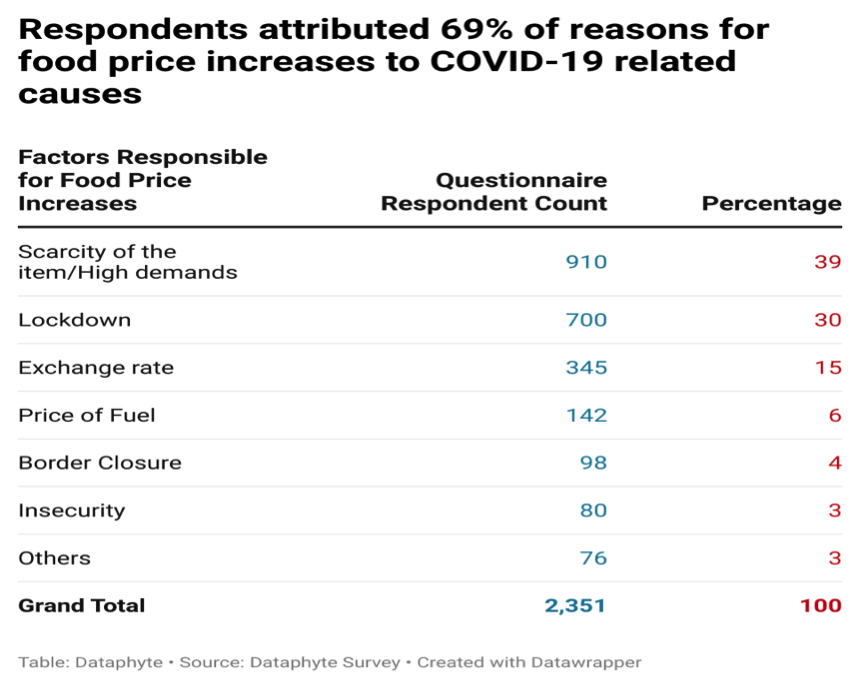

Further analysis of the responses of food buyers like Opeyemi Adeyemi implied that coronavirus-related activities accounted for about 69% of the increase in food prices in Nigeria within the period covered by the survey.

Like other nations across the globe, Nigeria adopted the ultimate measure to prevent the spread of the virus. By the end of March 2020, the government shut down its entire economy. This halted all production activities, movements, and major economic activities.

The shutdown affected farming activities, manufacturing, and all productive activities. Border closure further complicated issues as no supplements were coming into the country, creating a high demand for the few available items.

Insecurity and border closure played significant parts in the hike in food prices

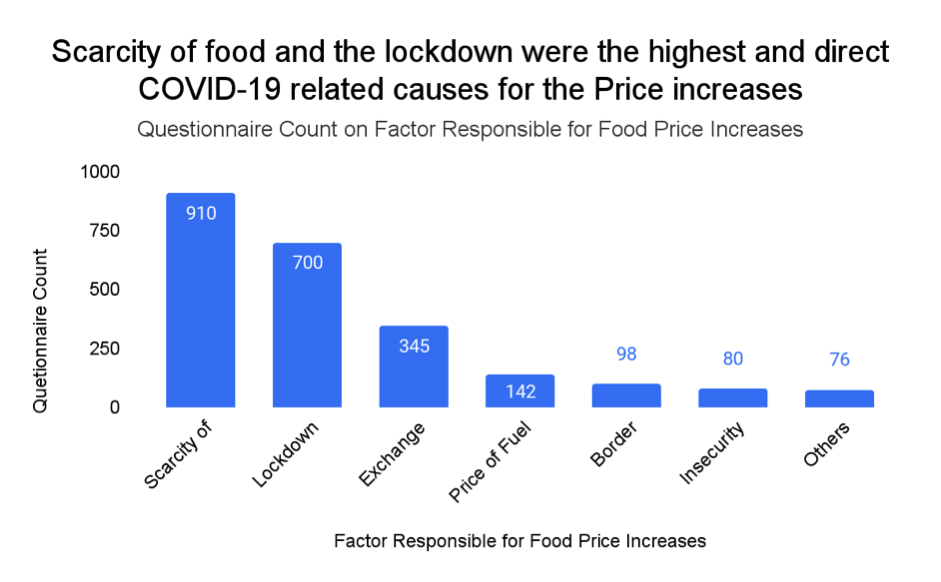

Dataphyte’s food price survey asked respondents in the 13 states what other factors they thought really contributed to the price increase. The goal was to understand what other socioeconomic factors Nigerians believed were causing food price hike during the period.

Based on the responses from 2,351 respondents who were surveyed, analysis showed that 1,610 respondents (69%) strongly believed that the scarcity of food items and high demand for the available food products during the lockdown period led to the price surge.

However, sustained violence and a general state of insecurity in the country, especially in the north-east, could have contributed to the scarcity of farm products and processed food items.

Other factors responsible for the food price surges include border closure, contributing 4%. General insecurity, terrorism, killings, kidnapping, farmer-herder clashes also directly contributed about 3% of the cause, according to the people interviewed.

The impact of high food costs on households run mainly by women

Morufat Oluyemi, a hairdresser in Arepo, Ogun state, south-western Nigeria, said she now engages in two jobs every day to be able to raise extra cash to cater for her four children after the demise of her husband.

“I have to shuffle between two jobs now. I own a hairdressing shop but the income can no longer sustain my family. I have to go for extra cleaning work as a cleaner to take care of the family,” Oluyemi said.

“Garri was once our saving grace but since the hike, it has been getting worse for my family. I just hope this stress ends soon. I no longer have time for children because of work-related activities.”

In the same Ogun state, a secondary school teacher, popularly known as Mrs Ajayi, who earns N50,000 (about $100) monthly said she is the family’s breadwinner.

“My husband works as a gateman in another school, and his salary is not forthcoming. During COVID-19, schools were shut, and owners did not bother to pay the staff remuneration,” she said.

“Presently, we manage what we have and cut expenses on foodstuffs because we have to pay for other house expenses and school fees of our children.

“It is terrible and the worst for us. I don’t even know how we have been coping and surviving under these current conditions.”

Price changes for each food item across sampled states

The survey results show that Benue, the state regarded as the “food basket of the nation” because of its large farming population and agricultural output, recorded the highest rate of food price increases in the country in the last year.

The state had the highest price increase rate for six out of the fifteen major food items surveyed.

Sokoto, on the other hand, had the lowest rate of food price increases.

Lagos, the economic hub of the country, and Abuja, the federal capital territory (FCT) also had very low food price inflation.

Dataphyte’s survey complementary to the Official NBS’

Dataphyte embarked on this recent market survey mainly to spotlight the effect of the COVID-19 on food prices. This involved interviews of buyers and sellers and a geolocation of the markets being reviewed.

The complementary survey sought to ascertain the level of food price fluctuations within the COVID-19 period and to establish whether the pandemic was significantly responsible for the price changes or not.

Dataphyte’s research team established, from over two thousand responses of buyers and sellers, that the COVID-19 shocks were significantly responsible for the rise in the general price levels of food items within the period.

The team’s analysis of other measures of economic performance and balance of trade figures within the period corroborates the people’s submissions.

What government did to cushion the high prices of staple foods

Governments at the federal and state levels made efforts, during the lockdown period, to provide food handouts to Nigerians, especially the poorest of the poor. Despite governments’ food distribution to tens of millions of the poor, the process was disorganised and marred by corruption. This later led to the looting of the food warehouses by citizens during the #EndSARS protests across the country.

Some believe that the government’s mass purchase of the staple food items at the scale it did led to the first artificial scarcity of the staple foods such as rice, beans, garri, spaghetti and vegetable oil. This is coupled with the difficulty in accessing markets to buy food, given the lockdown restrictions.

Nevertheless, the Nigerian government has not provided any intervention to curb or moderate the unending increase in food prices across the country.

What experts think government should do

To alleviate the effect of soaring food prices on the people, “It would be a contradiction for the government to buy food from farmers and resell to everyone especially if the same government is promoting a market-driven economy, Temitope Laniran, an economist from the University, UK commented.

Dr Laniran observed that “overall, the factors that make food price hike persist are structural challenges of the government. The foreign exchange rate is at a record high. This is compounded with the difficulty in accessing foreign exchange by businesses. Other social and economic infrastructure including security, ease of doing business, access to credit, robust value chain for agri-businesses are missing in the whole intervention equation”.

He suggested, instead, that “the government needs to first identify the factors responsible for the price increase. Then policy measures can then be instituted to curb the problems”.

When reached for comments on needed government interventions on the present exorbitant costs of food prices, Atiku Samuel, an economist and policy analyst, acknowledged that the government needs first to “open the border, (and) drop all restrictions and tariffs on food products”.

He further said “insecurity is a major driver which needs a comprehensive and inclusive approach by the government and other industry stakeholders. Government seems to stand aloof when making its policies, government officials seem to believe they have everything figured out scanning from the offices with less robust and inclusive deliberations happening”.

On his part, Tope Fasua, economist and a former presidential candidate, identified three ways on how the government can abate the hike in food prices despite disruptions of economic activities from last year’s COVID-19 lockdown. “One of the ways is for the government to develop commodity exchanges and ensure there are silos (ways of preserving what farmers produce) to prevent farmers from incurring huge losses.”

He said this would create a good structure to abate high prices and scarcity during the off-season period.

“Another challenge is insecurity, and the government needs to find ways to solve the menace and ensure farmers feel secure while farming,” Fasua added.

“The last one should likely be the price-setting mechanism. The government needs to use moral suasion by engaging associations, farmers groups and others to see how to set the price of a ‘mudu’ of beans or paint of garri in a way that would not exploit the public.”

Reporting by Aderemi Ojekunle, Ode Uduu, Charles Mbah and Joshua Olufemi. Data analysis and editing by Oluseyi Olufemi.

This report was first published on Dataphyte, and was produced with the support of the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships and Big Local News at Stanford University.

Add a comment