BY ANIBE IDAJILI

That night in February, Hajara Muhammed panicked as the lingering sound of gunshots rent the air. The marauding bandits had struck again. The assailants, in their hundreds, sent many residents away from their farms, rustled animals and carted away food items. Hajara, a 25-year-old mother of four, fled Shadadi community in Niger state, Nigeria’s north-central, with her children and never looked back.

Their new abode, temporary accommodation in Kontagora, a neighbouring community, was provided by a local businessman sympathetic to their plight. The building is also occupied by four other women who fled Shadadi with about 22 children — with ages ranging from five months to 11 years. Their skinny bodies and bulging faces tell tales of hunger and despair.

While in Shadadi, Hajara rarely had any need to buy food because the family farmed their own rice, maize, millet, guinea corn and yam, and the children had enough to eat. But they had to leave everything behind and run for their lives.

Since they no longer have access to their farms and source of livelihood, the women can no longer feed the children as much as they did while in Shadadi. They cook once a day, in the evening, and whatever is left of their dinner goes for the next day’s breakfast and lunch.

Advertisement

Shadadi has been the target of bandits, just as Bassa, Erena, Madaka, Kagara, Galkogo, Shiroro, Allawa, Tegina, Gwada, Kuta, Zumba, Gurumana and many other communities in Niger state. In the last two years, bandits have forced over 150,000 residents away from their homes across the northern states.

“The night the bandits attacked, they kidnapped 68 people, killed 15 others, stole our money and food,” Hajira said.

Too heavy a price to pay

Advertisement

Like Hajara, Jamila Abdullahi from Baban Rami community has been living in Kontagora with her 9-months-old baby boy for months. She is, however, at the Kontagora General Hospital, where her son is being treated for severe malnutrition.

After bandits ambushed farmers in January 2021, Jamila and her family could not visit their farms for several months. Over a year after, their lives have not returned to normalcy. It has taken a toll on her struggling family.

“I feed my son and other children with whatever we can afford to buy from the market, mostly fura (millet dough balls) and tuwo masara (cooked corn flour meal),” Jamila said as her eyes welled with tears. “We have become too poor to afford healthy meals or buy baby formula.”

Jamila’s predicament is similar to the plight of 56-year-old Aisha Aminu from Angwan Yanma community, who feeds her underweight granddaughter with bobo (a yoghurt-based milk drink for children) worth ₦50 ($ 0.12) and fish.

Advertisement

With thin, wrinkled skin and a general absence of subcutaneous fat, the little girl exhibits symptoms of severe acute malnutrition.

“She hardly eats. But whenever she feels like it, I give her tuwo shinkafa (a northern Nigerian recipe made from mashed rice). She was only 36-month-old when her mother passed away. Her father had to migrate to Kontagora; he was a mechanic in Kuchi before bandits invaded the community in March. He has abandoned her. Things are challenging but I am trying my best,” Aisha said.

Basira Hamza’s two-year-old daughter is also a patient at the Kontagora General Hospital. Basira travelled from Rijiyar Nagwamatse community to the hospital to seek medical attention for her malnourished child, who also suffers from diarrhoea and skin sores.

“She eats a lot of rice. I don’t know why this is happening,” a confused Basira said.

Advertisement

When bandits invaded Basira’s community in January 2022, they killed three residents and kidnapped 28 others, forcing her family to flee from Farin Shinge to Rijiyar Nagwamatse.

Basira, her husband and daughter escaped by scurrying into the nearby bush. Before the incident, her husband owned a small farm and ran a modest kiosk where he sold groceries, and she was a full-time housewife. They have not been able to raise money for a new shop or eat healthily seven months after arriving in their new home.

Advertisement

Although Hajara faces considerable challenges in feeding her children with proper meals, she believes that the situation is still preferable to living in constant fear of danger. After the initial emergency relief items provided by the government finished, they are now bereft of support.

“Luckily, our benefactor hasn’t asked us to leave this place,” she said. “I really want to go back home, but it’s too dangerous at the moment.”

Advertisement

The sense of uncertainty is the same for the other women. They no longer have the things they once took for granted.

Worrying statistics

Advertisement

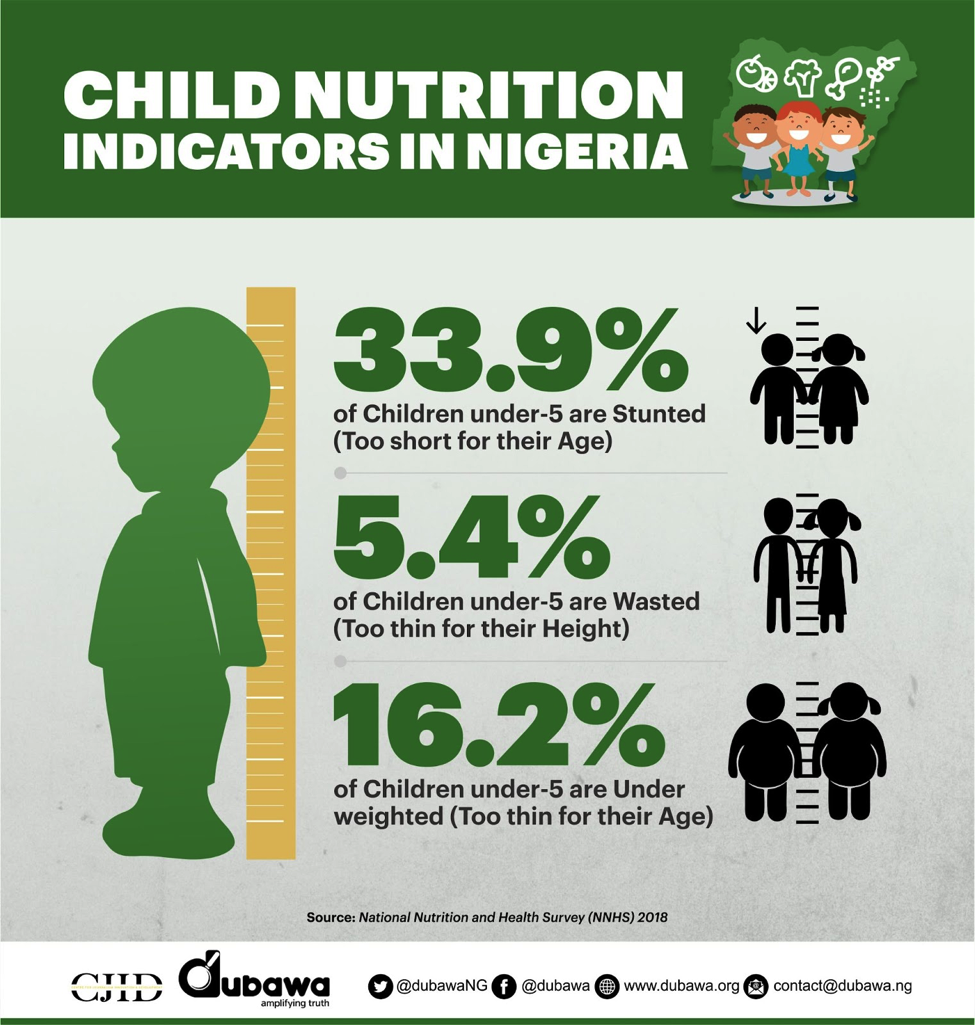

Hajara, Jamila, Aisha, and Basira’s children are just a few of an estimated 2 million children in Nigeria who are severely malnourished and stunted from not being fed a variety of foods, especially vegetables, fruits, dairy products, eggs, fish, meat, and fish.

A child is deemed ‘stunted’ by the World Health Organisation (WHO) if their height for age Z (HAZ) score is two standard deviations or more below the WHO child growth standard.

The statistics are even more dismal in most parts of northern Nigeria, where over half of all children are stunted, according to the 2018 Nigeria Demography and Health Survey. Current spikes in severe acute malnutrition cases in Nigeria’s northern region, according to UNICEF, can be attributed to a rise in insecurity.

According to a document on the state policy on food and nutrition, the under-5 mortality rate is unacceptably high at 123 per 1,000 live births, and malnutrition is one of the underlying causes of these deaths. Niger State is already home to high rates of undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies.

In fact, during an advocacy visit in 2021, Hajia Ramaru Umar, the state chairperson, committee on food and nutrition, informed the Civil Society-Scaling Up Nutrition in Nigeria (CS-SUNN) that over 21,000 children below 2 years in Mashegu and Mariga LGAs of the state were suffering from stunting and wasting as a result of malnutrition.

Despite these realities, nutrition response to emergencies like conflicts and insecurity has been limited in the state. The inability of displaced persons to grow, produce, sell or buy food has exacerbated hunger and malnutrition.

Other factors including poor maternal nutrition, ineffective infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices, insufficient health services and restricted access to nutrient-rich foods are at the root of malnutrition in the state.

Low budgetary allocation to fight malnutrition

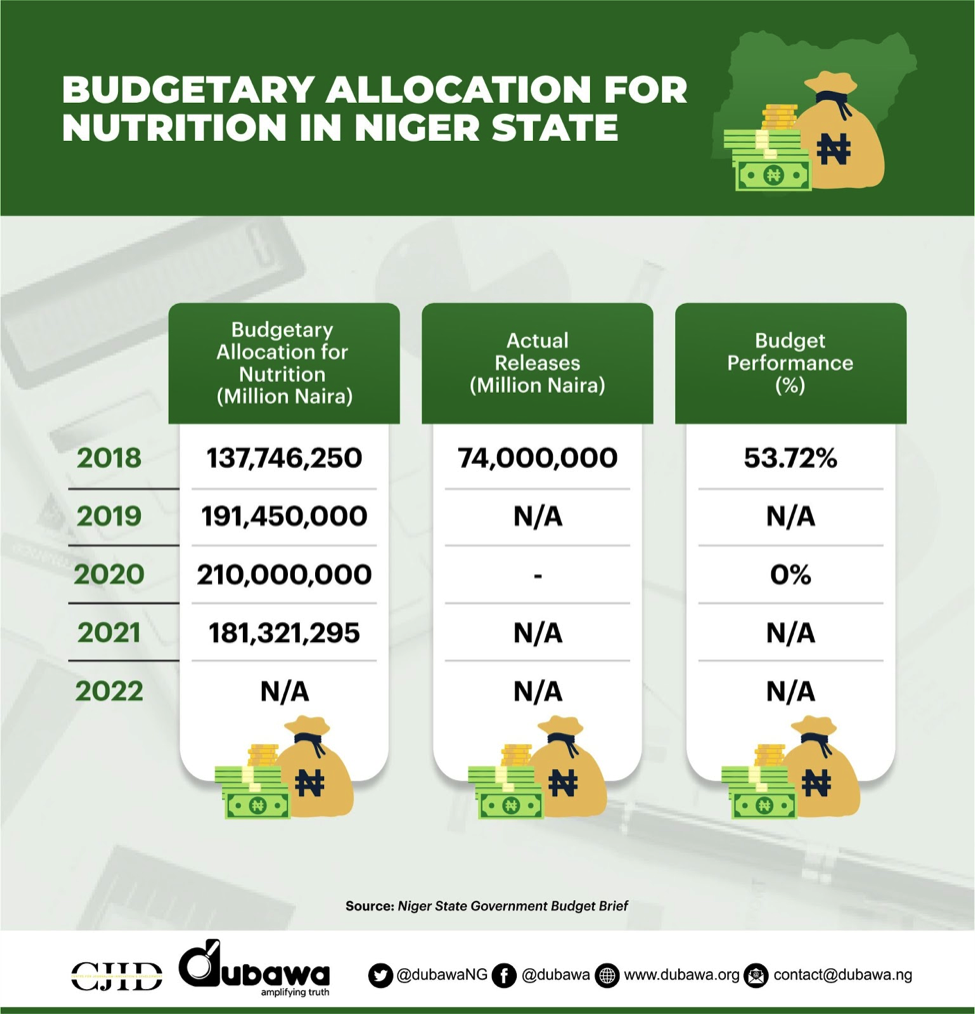

In 2021, the Niger state government earmarked ₦15.9 billion for its health sector, which was 4.8% less than the recommended 15% budgetary allocation for health in the Abuja Declaration on health.

A critical analysis of the budget document reveals that there is no budget line designated for nutrition, although there are budget lines set aside for donor-funded initiatives to combat child malnutrition.

While donors play a significant role in funding maternal and child health programmes in Niger, the state still has no identifiable programme on nutrition-related issues in the budget.

For instance, one of the main activities of the Saving One Million Lives for Result Program (SOML4result), a project to increase access to basic health services and supplies for the women and children of the state, is child nutrition.

In addition, the state depends on UNICEF for its counterpart contribution to the provision of certain nutrition-related commodities such as the Ready to Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF) and F-75 and F-100 therapeutic milk powder for malnourished children.

RUTF, a mixture of milk, peanuts, sugar, butter, vegetable oil, and mineral-vitamin complex, is used to treat severe wasting and prevent severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in children under five.

However, for over two years, government-run health facilities like Kontagora General Hospital have not had these commodities.

Investigations show that the state has defaulted in meeting its counterpart financial obligation, putting the programme under severe threat.

Asmau Mohammed, state chairperson, committee on food and nutrition, said the committee is finding a way around the problem and planning to put out a memo to that effect.

“The support UNICEF is giving is conditional. We are expected to contribute a matching fund. We are working on getting this done,” she explained. “Malnourished children still get some form of attention from the state. We provide counselling and other support to the parents of these children, especially with the current issue of banditry.”

Way Forward

Fatima Aliyu, the head of the emergency relief unit of Kontagora LGA, said the conflict situation in the last few months assumed an emergency dimension that required the urgent attention of the local and state governments.

“The attacks have displaced many persons, especially in Magama and Mashegu LGAs. Yes, we stand ready to provide emergency nutrition responses at the grassroots level. But what happens when the relief items stop coming?” Aliyu asked.

Ocholi Okutepa, the focal person at the inpatient and outpatient treatment of severely malnourished children unit at Kontagora General Hospital, said the number of malnourished children seeking medical attention has increased since banditry worsened.

“There is an urgent need to scale up funding for nutrition to address the needs of hundreds of children impacted by banditry. This is critical to prevent a massive malnutrition crisis for children in Niger state,” he said.

Muhammed Sani, the village head of Birnin Kwangwara, said, “Since the emergency interventions stopped, the victims of the crises who fled to the Birnin Kwangwara area of Kontagora have been surviving through the benevolence of some good-hearted people. They are really in need of a sustainable support system so their children can eat healthily.”

Tonia Emelue, a nutritionist, said the increasing incidence of child malnutrition could be reduced significantly if the state starts to produce RUFTs locally.

“The production of Ready to Use Therapeutic Foods locally will aid in lowering child mortality rates caused by malnutrition. Fortified milk, sugar, butter, vegetable oil, groundnuts, minerals, and vitamins are the main ingredients in RUTF. They help children in gaining weight quickly and are safe to use.”

The Niger state policy on food and nutrition says the target is to reduce the number of under-five stunted children from 38% in 2015 to 20% by 2025, and childhood wasting from 7.3% in 2015 to 3% by 2025.

Also, in 2021, the state government launched its Multisectoral Plan of Action for Food and Nutrition. According to the government, it is a viable tool for attaining the state’s sustainable development goals, scaling up nutrition activities and ensuring adequate budgetary provision and timely funds for nutrition interventions.

But for Musa Nasir, a Tegina-based health worker, the government might have lofty ideas for tackling child malnutrition. “But until every malnourished child in conflict-affected Shadadi, Mariga, and every community affected by banditry can access the needed nutritional rehabilitation, the war against malnutrition is yet to be won,” Nasir said.

Multiple calls and messages to Muhammad Makusidi, the state commissioner for health, and Sani Abubakar, the public relations officer of the ministry, were not answered.

This story was supported by the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) and the Institute of War and Peace Reporting (IWPR) under the Voices for Change Fellowship.

Add a comment