Spanish coastguards rescue three Nigerian migrants from ship's rudder after 11-day voyage from Lagos to Canary Islands... Photo credit: SALVAMENTO MARÍTIMO/Twitter

Days bled into one another as hunger gnawed at Adeleye. It seemed the cramped space he lived in also held him captive. Yet, amidst the oppressive darkness, the dreams of a better life beyond the horizons of the sea nearby continued to play in his head — visions of a life unconfined by the suffocating walls of Ajegunle, his slummy city in Lagos, Nigeria. Adeleye clung to these dreams.

As the ocean stretches before him, an endless blue highway promises escape. Adeleye knows that yearning for a better life and the journey across this vast expanse are no pleasure cruise. It’s a desperate gamble, a stowaway’s odyssey fraught with peril and uncertainty. But that’s the only way most men around this coastal community knows as the quickest pathway to a “brighter future”.

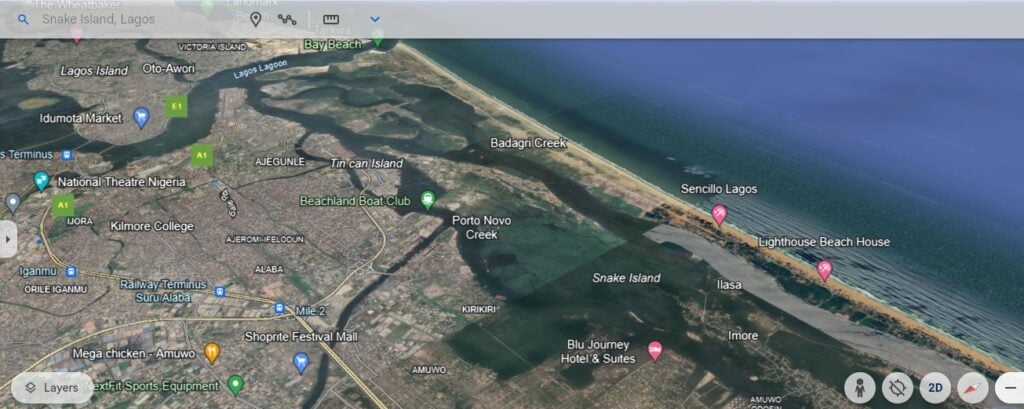

Ajegunle, a vibrant Lagos neighbourhood nicknamed “AJ City,” pulsates with life in the heart of Ajeromi Ifelodun LGA. Its history stretches decades back, once marking the boundary between the Western Region and the Lagos Colony.

AJ City sits beside two of Nigeria’s most crucial arteries – Tincan Island and Apapa Wharf, the nation’s biggest seaports. However, the constant flow of ships from foreign countries also creates a dangerous temptation for those seeking a desperate passage abroad.

Advertisement

Ajegunle’s story is a tapestry woven with contrasting threads. Some view it as a cradle of Nigerian music, a breeding ground for artistic talent that birthed legends like the prolific Fuji musician King Wasiu Ayinde. Others see it as a place of resilience, a community where hard work and hustle are the cornerstones of life.

However, Ajegunle also carries the weight of negative perceptions. Some paint a picture of a notorious slum, rife with poverty, crimes and prostitution. The term “most disturbing ghetto” hangs heavy, overshadowing the city’s spirit.

The truth, as always, lies somewhere in between. Ajegunle faces challenges and undeniable issues that demand attention.

Advertisement

Ajegunle wasn’t just where Adeleye lived; it was woven into his being. For 33 years, the neighbourhood’s essence had seeped into his very core. The dust swirling through the air wasn’t just an annoyance; it was a gritty reminder of countless hustles, a constant companion to the ever-present hum of poverty that hummed beneath the surface of life in Ajegunle.

Born in 1991, Adeleye was the second of six children, the only son in a family brimming with hope. Dreams of achieving something great flickered brightly within him, a stark contrast to the harsh reality of poverty swimming around him.

Determined to change his family’s fortunes, Adeleye decided to prioritise education. Yet, life, he often remarked, had a cruel sense of humour. Despite reaching primary school, his journey was cut short in JSS2, a basic class in senior secondary education.

Distractions swirled around him, and the weight of responsibility – the pressure to contribute financially to family needs – pressed down heavily. He was forced to leave school, and his education was temporarily put on hold.

Advertisement

“When I look back now, I had dreams. My childhood dream is to become a nurse (he smiled). I know you will be surprised why I picked nursing. It was one of our neighbours who inspired me. He is now in America as a professional nurse,” Adeleye told TheCable.

“When I was about to enter secondary school, that was when he started his nursing training. I loved the uniform he was wearing, and that was the funny reason why I started holding on to the dream of being a nurse.

“But, as you can see, I could not even finish secondary school, let alone talk about becoming a nurse.

“Ajegunle is a killer of dreams. You (pointing to the reporter who also grew up in the community) left and became something; you didn’t know what God had done for you. If you hadn’t told me you grew up in AJ City, I wouldn’t have believed my brother.”

Advertisement

Adeleye said he worked in different factories in Lagos with horrible welfare and poor working conditions, but he endured just so that he could eat and also be the “man” the family expected him to become.

But in 2021, that year was different. The grip of hardship tightened, squeezing the life out of even the most determined hustlers within Ajegunle. It was then that he found himself drawn to a different kind of adventure, one that hummed with danger on the fringes of the city. Snake Island, a local community opposite the ports, is the camp ground.

Advertisement

There, under the cloak of secrecy, he met with Tolu, a friend from years past. Time had etched lines on Tolu’s face that spoke of faraway lands and experiences Adeleye could only imagine. Tolu wasn’t hawking wares on the street corner. He dealt in the “business of escape”. Call it human smuggling or human trafficking, but they call it Japa, a Yoruba word for migration.

LIFE IN THE BELLY OF A SHIP

Advertisement

Tolu has three motorised boats, and his boats were vessels not for fishermen but for the desperate souls clinging to a dream of a better life beyond the horizon. Tolu, the man who knew 12 countries and counting, facilitated their passage as stowaways.

At Snake Island, Tolu runs a waiting area for travelers due to unpredictable vessel schedules. These travelers, including Adeleye, have no choice but to wait for an unknown departure time. To accommodate them, Tolu converted a two-bedroom apartment into a temporary camp.

Advertisement

Adeleye joined the others at the camp, all waiting for their chance to travel. What he thought would be a day or two of camping turned into about ten days. He was feeling discouraged at a point but Tolu kept stressing the importance of patience.

Despite the unknown dangers that lay ahead, Adeleye’s yearning to leave Ajegunle’s struggles behind far outweighed his anxieties. He persevered.

“It was like a film; I won’t lie to you. It was the 10th day that Tolu told me and three other guys that the vessel would be leaving that night,” Adeleye narrated.

“What I did first was to go and buy the food we would carry for the trip, which is a lot of gala (sausage), bread, and water. I also bought some biscuits and chewing gum to keep me awake at night

“Tolu did us a lot of favour because, without him, we wouldn’t even know what to prepare for or what item to carry for the trip. He gave us the list of items to buy and even supported us with some small cash.”

Adeleye also hinted that Tolu’s assistance is not entirely selfless. He explained that there is an informal agreement about a share of their earnings upon arrival.

By 10pm on the day of departure, Tolu signalled that it was time to go. At this point, the fear that he might die in the process intensified for Adeleye, but Tolu gave them a pep talk again, reminding them of why they decided to make the trip at first. The thirst to overcome poverty and make their lives better.

They took off and sailed deep into the sea, waiting for the vessel. According to him, he later understood that most vessels now use military escorts from the port to some distance in the sea.

Adeleye noted that they couldn’t join the ship from the port or close to the port because the water at that level was not deep enough for them to get into the ship.

So, Tolu planned that it would happen far into the deep waters, where, most times, the military escort would have turned back, giving them a good opportunity to enter the ship.

For Adeleye, a key sign of “divine favour” on his adventure was securing access into the ship on his first try. Tolu had warned them that success might require multiple attempts, just to prevent discouragement.

Tolu headed back to the camp to prepare the others for their journey, even though he expected them to make it.

Getting on the ship might seem like the biggest hurdle, but for Adeleye, that’s just the beginning. The real challenge is what comes after clinging on for dear life while your whole life flashes before your eyes. It’s a desperate fight to stay focused and reach your goal.

Once he and his three colleagues snuck onto the ship, their paths diverged. The first order of business is finding a hidden spot to hang, close to the water but fair enough to avoid being caught. Leadership is also crucial, he said. With a leader, the odds of success increases dramatically.

“We had to first look for a better position to hang so that we won’t fall inside the water and the crew members would not see us either,’ Adeleye narrated.

“Leadership is also key because, without that, the success of the journey is zero. The team made me the leader because they observed that I was very bold and courageous.

“Tolu had also told us the destination of the ship, so we have an idea of when it would arrive Togo, which also helped our patience.”

After four grueling days at sea, they finally spotted the coast of Lome, the capital city of Togo, a neighbouring West African country, around 4 or 5pm. Adeleye said the subtle changes in the water current and level tipped him off that they were nearing a port. Tolu had instructed them to try and get the crew’s attention once they were close to a port.

Adeleye, remembering Tolu’s advice, knew they had to make their presence known to the crew. He did just that, and unsurprisingly, some crew members came to investigate and found them hiding in the ship.

They were brought up on deck, given warmer clothes, and questioned. This was a small price to pay. They made it.

Upon reaching Lome port, the captain would inevitably contact the shipowner and other port authorities about the stowaways. Deciding their fate would be the next hurdle, but that is the light at the end of the tunnel for the deadly journey.

THE STOWAWAY BUSINESS

It’s a business, Adeleye reiterated. Europe was for those seeking a fresh start, a chance to build a future. But Africa was about the hustle; the game wasn’t just about relocation, it was about a payout.

Words on the street had it that there was a United Nations agreement – some kind of shadowy deal – that compels port authorities in African countries to pay a hefty sum when they catch stowaways.

TheCable could not independently verify such agreement or claim.

The plan was simple: get caught! Play the reluctant traveller, someone who’s been tricked or simply desperate. The shipowner would then be on the hook to pay the port authority, and that, in turn, meant a cut for everyone involved. Once the dust settles, he would figure out how to get a few thousand dollars – enough to change his life back home in Lagos.

“The business of stowaways is divided into two, depending on the aim of being a stowaway, which is also associated to the country the ship is going into,” Adeleye explained.

“Ships or vessels going into European countries are mostly used by stowaways for relocation or seeking greener pastures. But for African countries like South Africa, Cote d’Ivoire, Togo, Gambia, Senegal, etc., we are mostly interested in the money they will give us when we are caught.”

Lending credence to Adeleye’s claims, another young man named Boluwatife, 29, shared his experience of stowing away to reach four African nations. He revealed a system where payouts increased with the destination’s economic strength: $7,000 in Africa, $10,000 in South America, and a staggering $15,000 in Europe. This kind of money, he emphasised, could be life-changing back home in Ajegunle.

“When we enter any African country, the amount we get also depends on how their economy is doing. This is how it works: after we have been caught, the agent in charge of the port where we were caught will contact the ship owner, who is expected to pay each stowaway $7,000 based on the United Nations agreement,” Boluwatife said.

“Once the money is paid to the agent, he will take from his share of the money. He will take part of the money and bribe the immigration officers to allow them to deport us back to Nigeria without checks. The agent will also use part of the money to pay for our flight ticket to Nigeria and give us $1,500 to $2,000 in cash.

“That money that we get is the motivation for the trips. You might think that’s small money, but with the level of suffering in Ajegule, that amount is very big.

“How many jobs in Nigeria can give you $2,000 in less than a week? Imagine if we travel multiple times in a month; that would be a large amount of money for us here in Ajegunle.”

Boluwatife’s voice grew quiet as he explained the strange situations some stowaways face.

They weren’t thrown straight into deportation. Instead, some countries offered a chance to stay and navigate a real immigration process. Interviews, temporary housing, and even get help to find work – a far cry from the dark, cramped hold of the ship.

But the choice wasn’t always clear-cut. Some, after enduring interviews and uncertainty, were offered a way out with a one-time payment of $4,000. For many, that was a life-changing trip back home. The allure was undeniable, a fast track back to familiar ground, a chance to help their families immediately.

“In any European country or South America, we know that their economy is still better than many African countries. When we enter those countries, we have the mindset of staying. When we decide to stay, what the agent will do is take us to their immigration court, where we will be asked a lot of questions and later put in a camp,” Boluwatife said.

“In the camp, we can spend like two to three weeks sometimes, and they will be feeding and taking care of us. The human rights office of the United Nations also gets involved to protect our rights.

“From the camp, we are sometimes allowed to live in their country and work, or they send us back to Nigeria with our share of the $15,000. Some of us turn down the offer of staying in the country and we get $4,000, which is a lot of money compared to what countries in Africa are paying, hence why we always wish for such vessels.”

Getting a visa is a pipe dream, a luxury Adeleye could not afford. But the stowaway game, he had learned, had its twisted logic.

“They treat stowaways better than visa guys,” Adeleye chuckled humourlessly, explaining the system to the reporter. “You get caught, the government takes care of you. Food, shelter, even help finding a job.”

“The reason why the shipowners are making sure they pay us and also the agents and immigration is that if the government of the country finds out that we are there, it is the fault of the shipowner who refused to double-check his ship before entering the other country.

“That is why they are also trying to cover it up, and the reason they are not giving us the money directly is that they feel we won’t return to our country if given the money. If we do not return and the government finds out, it is big trouble for both the shipowner and the agent.”

HOW WE LEARN ABOUT SHIP MOVEMENTS

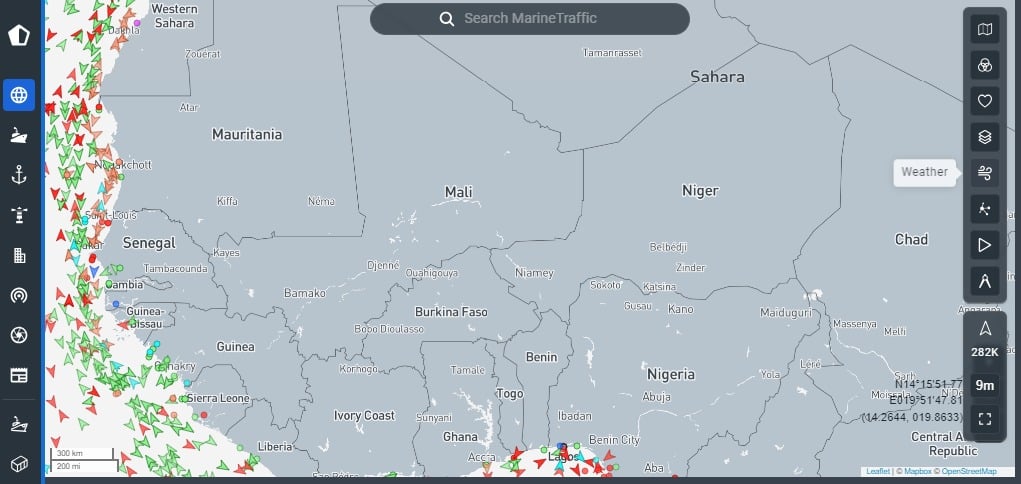

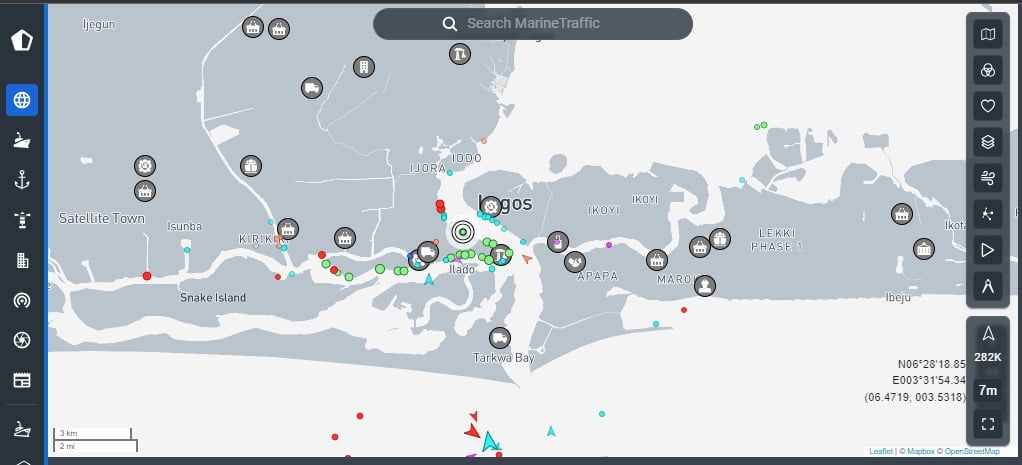

The flickering light from Boluwatife’s phone cast an eerie glow on his face as he scrolled through the website – MarineTraffic. It wasn’t a site for booking luxury cruises, but a lifeline for people like Tolu, Boluwatife and Adeleye. This website, according to them, held the key to a gamble — a treasure map — for a new life across the vast ocean.

MarineTraffic is a maritime analytics provider that was primarily built to provide real-time information on the movements of ships and the current location of ships in harbours and ports.

With a practised eye, Adeleye said he could decipher the ship movements, their scheduled departures, and most importantly, their destinations. This information, he said, is the difference between a life-changing escape and a watery grave.

By filtering based on departure dates, destinations, and even ship type, Adeleye could choose his gamble wisely. Cargo ships with large engine rooms offered potential hiding spots. Those with scheduled stops in wealthier countries, like Europe or South America, promised a bigger payout if caught.

“What kills a lot of people is that they don’t know the destination of the ship before they enter it. They, sometimes, finish their food or the water current increases, and they cannot bear it anymore,” Adeleye said.

“Ships are of different types; there are some that, when we enter through the part of the propeller, we can still climb a certain height that can help distance from the water, and it is very spacious. But some don’t have that space, which means we have to hang till we arrive at our destination.

Boluwatife said using websites like MarineTraffic, they estimate travel time. If a journey is for nine days, they aim for a “breakthrough” by day six or seven. Their logic? The ship would be too far out to turn back for some stowaways.

After they have been caught, they hope for acceptance by the crew. Food, water, and a chance to explain their reasons for escape – a heartbreaking story of hardship that might earn them a sliver of sympathy.

THE STOWAWAY’S OFFERING

Amidst the stench of sweat and fear in the belly of a ship, a different kind of battle is being waged – a battle for survival that transcends the physical realm.

The veil between the physical and spiritual thins considerably at the port, according to Adeleye and Boluwatife. Here, a different kind of security is needed – not just against the propeller, but against unseen forces as well. Shipowners and agents, they explained, engage in their own rituals to ensure a safe voyage.

The most potent, they said, involve a sacrifice. The blood of a goat sprayed around the vessel like a crimson shield is a plea for protection. The offering isn’t complete without the goat itself being cast into the churning sea, an appeasement to the spirits that dwell in the depths. This ritual, they believe, isn’t just about fending off pirates or rough seas. It is a way of protecting the captain and crew, a pact made with the unknown for a smooth journey and a safe return.

They both spoke of appeasing Mami Water, the powerful river goddess of Nigerian lore who held dominion over the very waters they desperately cling to. To ensure calm seas and safe passage, they believe an offering is necessary. A token of appreciation, a Nigerian naira note clutched in their hand, a necklace, anything to acknowledge her power and plead for her favour.

“Once we leave Nigeria’s waters, we make spiritual sacrifices. We used to beg Mami Water to allow us to pass freely. Because we are in very close proximity to the water, we have to drop whatever naira we have on us inside the water at different intervals. That is like a sacrifice to please the god of water,” Boluwatife said.

“You might not believe me, but that process is a spiritual one, and you can not use ordinary eyes to make that trip.”

A DISTURBING TREND

People risking everything to reach a new life isn’t a new story. A recent report by Gard, a marine insurer, shows that Nigerians are at the forefront of the stowaway trend.

The report exposes African ports, particularly Lagos, Conakry, Dakar, and Durban, as hotspots for stowaways attempting desperate voyages.

The data, spanning 2013 to 2022, paints a disturbing picture. The term “stowaway” isn’t merely someone sneaking aboard. As defined by SOLAS, the international maritime treaty, a stowaway is someone hiding on a ship without permission, putting themselves at immense risk of discovery, harsh conditions, and even death.

Nigeria emerges as a major source of these stowaways, with 14 percent of all stowaways during the analyzed period originating from the country. Following close behind are Morocco (13 percent), Guinea (12 percent), Tunisia (8 percent), and Senegal (7 percent). The remaining 46 percent comes from other African nations.

In November 2022, Spanish coastguard found three Nigerians on a ship’s rudder after eleven days voyage from Lagos to Canary Islands.

In February, the Nigerian Navy arrested nine stowaways hiding in a rudder compartment of Spain-bound ship.

Between the span of nine months – August 2023 and April 2024 – the Nigerian Navy said its operatives apprehended 75 stowaways on Lagos waterways.

According to Aiwuyor Adams-Aliu, the navy’s director of information, 52 stowaways were arrested between August and December 2023 at different places on Lagos waterways, and the other 23 were nabbed between January and April 2024 on the Lagos channel and fairway buoy.

“During the operations, the QRT carefully extracted the stowaways who had concealed themselves inside the rudder compartment of the vessels,” Aliu said.

“All apprehended stowaways were handed over to the Nigeria Immigration Service (NIS) in accordance with the established protocols for further necessary action.

“The NN wishes to enlighten the general public on the dangers of attempting to travel as a stowaway. These include severe legal consequences and significant health risks such as negative effects of harsh weather conditions, lack of food and water, injuries, and even death.”

When stowaways are discovered on board, Gard’s guidelines emphasise prioritising their safe disembarkation and return home (repatriation). This involves immediate communication with the shipowner, insurance provider (P&I Club), and port agents at previous and upcoming destinations.

While Adeleye, Boluwatife claim financial gain as their motivation, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) discourages any payments or benefits beyond basic necessities like food, water, and medical care. This is to discourage others from attempting the dangerous stowaway route.

For individuals seeking asylum, Gard suggests reaching out to immigration authorities at the next port. If they consider the asylum claim genuine, they will usually take responsibility for the stowaway. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) can be involved if authorities refuse to disembark someone with a strong asylum case. Unfortunately, the shipowner may be required to provide financial guarantees to cover detention and repatriation costs in such cases.

Ultimately, if asylum is not granted, immigration will arrange for repatriation to the stowaway’s home country. However, the shipowner often bears the financial burden of this process.

According to Hellenic Shipping News, stowaways pose a significant financial challenge for shipping companies. Not only is the repatriation process complex, involving the often-reluctant transport of people across continents, but the costs have also risen dramatically in recent years.

Data shows a jump from an average cost of $7,000 per stowaway case for insurers in 2002 to over $18,000 by 2008 (excluding deductibles). These figures can skyrocket even further when dealing with multiple stowaways, as security regulations often mandate two guards per person for repatriation.

‘ALL DIE NA DIE’

A port facility security officer (PFSO), who requested anonymity, revealed that stowaways employ a variety of methods to sneak inside ships.

“In my experience as a PFSO, I can categorically say there are numerous ways and not just a single way stowaways can gain access to a vessel,” he said.

“This is either by conniving with stevedoring on board vessel disguising as a stevedore, or by pretending to be Chandler agent, or by the use of boats or swimming to the starboard area and hide in rudder trunks.”

He noted that the preventive measures used at the ports are human intelligence gathering and company security procedures.

According to him, rudder trunk are checked before vessel departure by both the vessel master and ship security officer (SSO).

“The SSO is asked to sign a declaration of security (DOS) to agree that he has done due diligence by checking all the cabin, container stacked areas, and rudder trunk to ensure that there are no stowaways on the vessel,” the officer said.

“Also, the jetty area or the berthing area is fully guarded with armed security operatives.

“Constant security patrol, routine semi-discretional patrol, and Aberdeen patrol of both the waterways, jetty, and berthing area will deter stowaways.”

For 26-year-old Bolaji Adetunji deterrent is one thing, motivation is another. But the latter often trumps the former. According to him, life in Ajegunle is cruel and unforgiving.

As a first child of five children, he yearned for a way to break free and build a better future for himself and his family. He had the list of those who had tried the adventure and perished in the sea. Those who succeeded narrated all the risks. Though some died, some succeeded, he thought.

“My father is late, and I am left to struggle to feed my siblings. What would I have done? I had to do something to prevent hunger from killing us,” Adetunji told TheCable.

“All die na die. So, I have to choose the stowaway path.”

All die na die is a Pidgin English statement which roughly translates to “Death is death no matter how it comes” or “We will all die one day; how it comes doesn’t matter”.

As a bus conductor and former commercial motorcycle operator, his joy knew no bounds when his first trip in 2021 as a stowaway fetched him $2,500. The experience hardened him, turning him into a man who could navigate not just the world, but even the treacherous depths underwater.

The second trip in 2022 yielded a reward of $1,800, a sum that jumpstarted his dreams. He used a portion to open his barbershop, and the rest, he shared with those closest to him.

Despite the success of his unorthodox journey, Adetunji wouldn’t recommend it anymore. The risks, he acknowledged, were escalating with each passing day. His experience was a product of a specific time, and he wouldn’t dare tempt fate or encourage others to do so.

Add a comment