The marks of old age were only apparent on Regina Wazani at close range as she moved about gingerly, tending to the activities that her work required. Washing, peeling, boiling, and frying were the routine of her business.

At over 60 years old, Wazani is not tired of providing Borno residents with their favourite snack: fried grasshoppers. Stirring an insect-filled cauldron boiling adjacent to her shop, the sexagenarian slipped into the past — recalling the heyday of the business. Those were the days a lot of money flowed in, “too much to count”.

“Back then, the money came in huge sums,” Wazani said, throwing intermittent glances at the bubbling cauldron.

“I didn’t know how to manage it or what to do with it because the income was beyond measure. There was a lot of market, and the money came in hugely.”

Advertisement

Wazani was said to be the second person to ever fry or sell grasshoppers in Wulari, a community in Maiduguri, Borno state capital, whose most documented story is one of grief from the horrors of the Boko Haram insurgency.

She and her friend, Rebecca Buba, whom she fondly called Mama Mbiu, started the business in Wulari 50 years ago. Mama Mbiu passed on in 1999, leaving a house behind as part of proceeds from the business. The building now accommodates children who tell the tales of her enormous achievements from the trade.

It is now 25 years since her partner died and Wazani is still thriving in the grasshoppers trade, bearing the weight of a rich history of prosperity and the unpleasantness of inflation which now dangles at 33.4 percent in Nigeria.

Advertisement

“Everything is expensive and the income is not the way it used to be,” she lamented.

“Oil is now expensive. A small jerrycan of oil is N35,000, while a big one is about N55,000.”

Wazani, while insisting that “the market has crashed”, told TheCable that she earns between N20,000 to N30,000 weekly when business is good, and gets about 10,000 weekly on bad days.

But a drop in earnings is not the only change that has occurred since she ventured into the trade. The business has grown and completely spread throughout the north-eastern state.

Advertisement

Despite the large-scale insecurity in the state, Borno houses a capital that is now regarded as “the headquarters of grasshoppers trading”, due to the popularity of the business in Maiduguri. Locals call it ‘fara’ business. Fara is the Hausa word for grasshopper.

TheCable’s investigation revealed that through the business, some residents of the state are gently plotting their way out of poverty, which has affected 20.47 million people in the north-east region.

‘IF YOU KNOW WHAT’S IN FARA BUSINESS, YOU’LL QUIT YOUR JOB’

Advertisement

In spite of Wazani’s complaints about revenue decline, traders and residents who spoke with TheCable said the business is booming amid Nigeria’s harsh economic realities.

“I started the business because I couldn’t get a job when I finished secondary school,” said Happy, who is now a trader.

Advertisement

Starting with N35,000 capital five years ago, Happy now earns N50,000 weekly and caters to her needs.

“Business is good now and I thank God. I feed myself and do everything from it – including rent,” she added.

Advertisement

Like most small businesses, the grasshoppers traders operate on a subsistence level, but the merchants among them with more capital often record bigger gains.

For instance, Mary Moses, who has been in the grasshoppers business for 30 years, has built a house in Wulari, and ensured her five children got education up to the university level.

Advertisement

“Three went to the university; two went to the polytechnic. One is still in school,” she said.

Similarly, many dealers like Sunday Ayuba and Alkali Umara have bought and built houses from the business. Umara said he has five children in private schools and “maintains” his two wives from the business.

“If you know what is in this fara business, you’ll stop this job you’re doing,” said Amina Bukariyama, a grasshopper trader in Borno.

EXPORTING TO SAUDI ARABIA, JERUSALEM

Bukariyama’s comment may have sounded caustic in an attempt to describe the profitability of the business, but she is one of the most successful grasshopper traders in the community.

Kicking off the venture in 1997 after her secondary school education the previous year, the insect trader now exports grasshoppers — fried or boiled and packaged in cartons and sack bags — to neighbouring countries like Cameroon, Niger, Chad, and Ghana. She also exports the product to Saudi Arabia, and Jerusalem.

“I also have a customer in Lagos. Sometimes, I send 30 to 35 bags to different states in a day,” she said, easing herself into a chair to resume de-winging a tray full of grasshoppers.

“I have friends that used to call. We’ll buy and send it to them in the US and the UK,” said Abdullahi Usman, president of the Borno Chamber of Commerce, Industries, Mines, and Agriculture (BOCCIMA).

The global insect food industry — largely dominated by Asian and European Union (EU) countries — is expected to witness a significant rise due to the increasing consumption of edible insects. The market is estimated to reach $17.9 billion by 2033, with volumes growing to as high as 4.7 million tons.

Crickets, mealworms, black soldier flies, ants, silkworms, cicadas, buffalo worms, and grasshoppers are insects that make up the market.

There are 2,300 insect species worldwide, with 28 percent considered edible in Africa, according to a research publication on the United States National Library of Medicine website.

In Africa, the industry is expected to hit $282.9 million by 2033, said Meticulous Research, a market intelligence firm.

Available data indicates that private sector investment in the industry is increasing “in an alarming rate” in African nations like South Africa, Kenya, Uganda, and Egypt — the leading insect food markets on the continent.

These investments are said to target large-scale production and supply to the marketplace of insect protein, particularly abroad.

In Kenya, a lot of money (grant or development funding) is going into research, said Laura Stanford, the chief executive officer (CEO) of Loop Pet Food, a Kenyan insect-based animal feed manufacturer.

Companies like Ecodudu, BioBuu, InsectiPro, and Uganda’s Marula Proteen have also received significant funding, she said.

“So, I think if we separate the money that is coming in, there’s a lot of investment, equity and debt, into some of the players that are operating on the continent at the moment. One of the biggest would have to be Maltento coming out of South Africa,” Stanford said.

“Then, you’ve got Sanergy, which is now known as Regen Organics, in Kenya. I think they are probably also one of the biggest players that have attracted the most funding and this includes equity and debt and grant funding.”

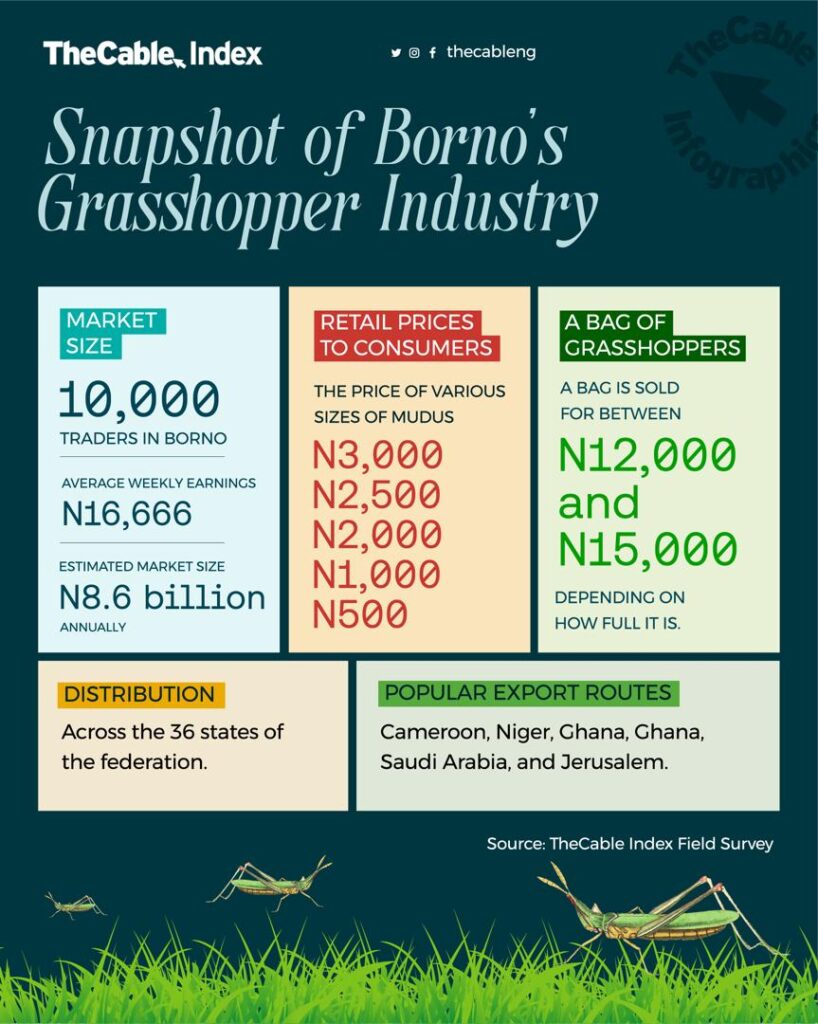

Although still nascent in Nigeria, with 10,000 traders in the state and each earning an average of N16,666 weekly, the Borno grasshoppers market is estimated at N8.6 billion annually, according to TheCable calculations.

WHY FARA IS CONSUMED

TheCable also observed that the growth of the business is largely dependent on consumption driven by “sweet taste” and the belief that “eating grasshoppers is medicinal”.

Residents say consumption is also cheaper when compared to meat, as a handful of the fried insects can be accessed for just N200.

“It’s sweet. Meat has now become expensive. But with N200, you can buy grasshoppers and it will be okay,” said Shuaibu Tijani, a businessman.

HOW THE BUSINESS WORKS

In Borno, grasshopper snacks production involves three major value chains: catchers, dealers, and fryers. None of them requires any scientific process or machinery to function. No rearing process is involved since the traders rely on nature for its seasonal supply of the insects in the wild.

While anyone with resources can participate in the last two segments, catching requires special skills and grit, TheCable learnt.

Often called “catchers”, grasshopper hunters are sponsored by the dealers who provide them with funds to buy kits required for the job.

“You get sack bags from the market and sow into a ‘shirt and trouser’, wear boots, and put a torchlight on your forehead,” said Peter Tah, a former catcher.

“You also need to carry another sac bag which is used to store the grasshoppers for sale at the market the next day.”

Catching is done in forests located in various rural areas including Monguno, Ganze, Gajigana Gubio, Benishek, Tunkushe, Sebudu, Jagan, and Main,” said Tah, also a former chairman of the Grasshoppers Trader Association of Nigeria (GTAN).

Women are not allowed to participate in the catching of grasshoppers because of the dangers involved as they often operate at night and are prone to attacks by the Boko Haram insurgents.

For more than a decade, Borno has been a hot zone for armed conflict, leading to the displacement and deaths of thousands of people and forced closure of schools and businesses.

Traders told TheCable that catchers have encountered Boko Haram fighters in the forests on many occasions, although they were not harmed.

“We’ve also met armed robbers a few times on the road before, but not anymore,” Tah added.

Tah said when the insects are caught, the catchers take them to their sponsors (the dealers) who then buy at a rate ranging between N10,000 and N12,000 per bag depending on the quantity of each bag.

A catcher could get as much as “30 sac bags” of grasshoppers per night – all disproportionately filled.

According to Tah, the dealers sell to the women who then fry and sell to consumers.

“When I buy it (the insects) from the market, I’ll soak it in water for 20 minutes. Then, I’ll move them into a big bowl for more washing. After washing, I’ll then boil it with salt. You can peel the back before or after boiling, then you can start to fry,” Esther Yakubu, a trader, explained the frying process.

‘NO MARKET FACILITY, NO CAPITAL’

Speaking on the boom and the business’ lucrativeness, Jonathan Maina, the president of GTAN, said insect trading is employing many in the state, especially youths who take up the venture mostly due to the lack of jobs.

Borno has an unemployment rate of 43.2 percent, according to data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

The industry is thriving in the face of threats that could do more damage than inflation’s profit-nibbling effect.

There is no permanent marketplace for merchants. TheCable observed that the current grasshoppers market, called “Kasua Fara” in Hausa, is an open space with trees sheltering traders from the region’s scorching sun.

Before moving to Kasua Fara, traders were based in a place known as “Shagari Locust”, but the state government evicted them following an incident that claimed a life.

“The second place — Kasua Fara — where we currently are, we’re facing more challenges because the people that own the land are still disturbing us to look for a place to stay because they’re not going to allow us to stay there forever,” said Aishatu Barba, the association’s chairlady.

The lack of capital also compounds the problem, TheCable understands. Traders said they are struggling due to insufficient capital amid the high cost of the grasshoppers, groundnut oil, and firewood used as fuel for frying.

As a result, some traders had to cut the quantity of grasshoppers they buy to half a bag, TheCable learnt.

“Sometimes, they would complain that they do not have money to buy another bag,” Barba said.

“So, that’s why we do call on our government to assist the association so that they can help our women, men, and youth to stand on their own,” the group’s president said.

“It’s not everybody that can look for government work after finishing their education. So, that’s why we are praying, and asking the government to help us to get a standard place.”

Maina told TheCable that the association used to pay taxes to the state government, but it stopped because its challenges were often ignored each time they approached the authorities for help.

He said the group intends to start paying taxes again when the government is ready to support its members.

WHY GOVERNMENT SUPPORT MAY NEVER COME

Speaking on the complaints of the traders, Usman, BOCCIMA president, said there is a history of secrecy in doing business among the residents such that it becomes difficult for “a son to know what his father is doing” unless he picks interest.

Usman said this tradition has continued to date — making it very difficult for the government to support any business.

Another issue, Usman said, is that most businesses — including the grasshoppers traders — are not registered with the chamber.

“We have less than 100,000 members as of now, despite the publicity, the enlightenment. This is simply because people feel they should keep to their own businesses,” he said.

“If they come to us, they believe we will exploit them. If the government wants to start taxing people, they’ll come to us first because we’re organised. That’s their thinking.”

He said once the traders register under the chamber, experts will be invited to educate them about the species of grasshoppers and build their capacity.

Usman believes that if the government improves the industry, the exports “will go haywire.”

“If this is properly controlled, harnessed very well and then value is properly added, it’s well-registered, maybe by NAFDAC, it becomes a flourishing business,” he added.

“But even as localised as it is, they still make a lot of money despite the insurgency that stopped them from going far into the bush.”

TheCable could not get the Borno government to comment on the challenges of the traders as attempts made over a three-week period to reach commissioner of commerce yielded no results.

IS GRASSHOPPER CONSUMPTION SAFE?

Typically, entomophagy — the practice of eating insects — is uncommon in Nigeria. This has raised concerns about the safety of consumption.

Olusegun Lawal, a professor at the department of zoology and environmental biology at the Olabisi Onabanjo University (OOU), said grasshopper consumption is safe — but it must be well prepared.

He said the winged creature contains more protein relative to fish and can also serve as feed for animals.

“When it is well prepared, it becomes nutritious,” Lawal said.

“The preparation we are talking about relates to the environment in which it was extracted. Number two, the process of cooking is very important because if it’s not well prepared, it could contain microorganisms that could break one down if consumed.”

Azeez Salawu, the executive director of Community Action for Food Security (CAFS), supports Lawal’s argument on the safety of grasshopper consumption. More specifically, he said the insects have some essential “vitamins and minerals like zinc and iron”.

“So, they are very safe for consumption,” he said.

The executive director, however, advised that care must be taken in the process of harvesting and preparing them for food.

“For instance, if they are gotten from an open space, you would know if they have been infected from what they have consumed in that area,” Salawu said.

“So, all we just need to do is to properly clean them up and cook them to avoid any potential contamination, and if we’re going to cultivate them, we need to make sure there’s no disease affecting them.”

The food safety expert was also optimistic that insect consumption could become a viable revenue-generating business in Nigeria, stressing that it is the future of agriculture.

However, the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) was silent on the subject matter.

In a statement to TheCable on the safety of eating grasshoppers, the agency said it is an area of coverage for public health officers “since they are not packaged” food.

“There is no research on it in NAFDAC,” the statement said.

Whether the experts agree on safety or not, Wazani is pleased that the business is improving the lives of Borno residents, employing “thousands of youths”, and curbing hunger.

But she wants the problems to go away.

“I am urging the government to intervene, to invest in the grasshopper business. I have spoken to so many media outlets, people, but nobody has assisted us,” Wazani said.