The news dominating the headlines now is President Buhari’s refusal of assent to the Electoral Act (Amendment) Bill 2021. While the bill includes other important provisions aimed at patching up our admittedly raggedy electoral process—electronic transmission of results, for instance—it is the proposition of direct party primaries that constitutes the big bone of contention. It is as clear from the president’s letter to the National Assembly giving his reasons for withholding assent as in the torrent of reactions by citizens and civil society organisations (CSOs).

The president is concerned about the financial, security and legal consequences of signing the bill into law. He thinks that direct party primaries would infringe on the rights of Nigerians to participate in governance and democracy, ironically the very thing that patriots and CSOs insist the bill will promote! In his words, the “amendment as proposed is a violation of the underlying spirit of democracy, which is characterised by freedom of choices (sic) of which political party membership is a voluntary exercise of the constitutional right of freedom of association.”

And this also is my point of disagreement with those who have pilloried the president and urged the National Assembly to override his veto by way of a two-thirds majority vote. As it happens, however, many of the president’s critics are not only friends and comrades in the struggle for democracy during the long years of military dictatorship, several like myself even being jailed for our pains, but also CSOs, the constituency that I served for two decades in the heyday of military tyranny as a student and human rights activist. Take, for instance, the well-reasoned argument of my good friend right from our days in the National Association of Nigerian Students (when there was a body properly by that name called), Samuel “Big Sam” Adegboruwa, SAN. Not an easy task disagreeing with him, but differ I must, not in the form or even substance of his argument—it being legalistic in the main—but in the spirit of what democracy truly enjoins on us. In other words, what makes it possible for both President Buhari and Adegboruwa to lay claim to the same motive: democracy, freedom of association and popular participation in choosing those to govern us.

But more than a worry over disagreement with fellow-travellers is the fact that mine has been among the many voices clamouring for electoral reforms—see, for example “The Time for Genuine Electoral Reform is NOW!” 27 April 2016, and, also, “Why APC Must Enact Change by Jettisoning Indirect Rule,” 13 September 2018. So, then, how do I now differ from the prevailing sentiment? In a small but crucial way. I will explain. It will be noticed that the subject of the first article is a general call for electoral reform—including the need to curb the costly timidity or connivance of the Supreme Court in substituting its opinions for the will of the people in electoral matters, with the 2008 report of the Justice Uwais panel as immediate point of reference—while the second article is a direct appeal to the All Progressives Congress of which I’ve been a member since 2014. And it turns on the narrow issue of freedom of association, a dispassionate discussion of which, I believe, will make President Buhari, whatever motive may be attributed to him by his critics, closer to its letter and spirit than might be readily admitted. We must be instinctively suspicious of power, but I think we must also be ready to concede when a valid argument is made in support of an official action, even when we are opposed to it.

Advertisement

I differ from the view that party primaries be made legally mandatory because that would be a clawback from the full purport of the constitutional guarantee of freedom of association. Political parties may loom large and enjoy enormous prestige, especially where they produce presidents, prime ministers, governors and legislators, but in reality, they are just like any other association of citizens formed for any number of causes, power or governance among them. Crucially, they are voluntary associations. Moreover, they are not agencies formed by or for the government, which would make it necessary to regulate every aspect of their activities by law. This, in a nutshell, is what the president poignantly pointed out in his letter to parliament, even when so much on the defensive that he could not forward it until deadline day. Amending the electoral law to prescribe direct primaries as the one and only means by which political parties can choose their candidates is, the president argues, “a violation of the underlying spirit of democracy, which is characterised by freedom of choices.” Then he added the clincher: “Political party membership is a voluntary exercise of the constitutional right to freedom of association,” stating the obvious, that “millions of Nigerians are not card-carrying members of any political party.”

I have no doubt that those who think that President Buhari’s refusal of assent is entirely driven by partisan and selfish reasons would not argue the contrary view. They can’t be heard to say that political parties are not voluntary associations of individuals with a partisan view of society and governance for which they seek power in order to actualise it. As a result of their crucial role within the framework of electoral democracy, however, certain conditions must be prescribed for their registration and participation in the electoral process. And by and large, the extant electoral act supplemented by any guidelines that the Independent National Electoral Commission issues in exercise of its powers, sufficiently take care of that need. That political parties are not the fons et origo, the source and origin, or beginning and end of democracy can be seen in the fact that independent candidates can and ought to also be able to seek the mandate of the people. So, then, what amendment should be proposed for them—that direct primaries be conducted by INEC for all individuals who indicate their intention to run for political office, at which all the relevant constituents not members of any political party would vote?

I make the last point, of course, only for the sake of argument but, essentially speaking, parties should be free to choose their candidates through consensus or, failing that, direct or indirect primaries. If they sideline their members—we must always be reminded that it is an internal affair of the party—they run the risk of angering them and the ensuing discord and disenchantment could prove disastrous to their hope of winning the election at stake. They should know that rival parties would only be too happy to exploit any disaffection caused by disenfranchising their members. That, in my view, is enough reason for the leaders of the parties to be very cautious in choosing the option for selecting their candidates. It is true that a coincidence of the lure of office as a sure means to power and affluence on the part of politicians, and grinding poverty and deep alienation from government on the part of the masses of the people has led to the enthronement of money as the arbiter of all of our elections, and that consequently this in-built check to the subversion of party members’ participation in choosing candidates has little or no effect. Nevertheless, laws should never be enacted to void the vital civic obligation of responsibility. Part of our problem is over-legislation: just see how voluminous our constitution is yet how frivolous our regard for it, how ineffective it is as our foundational document of nation-building!

Advertisement

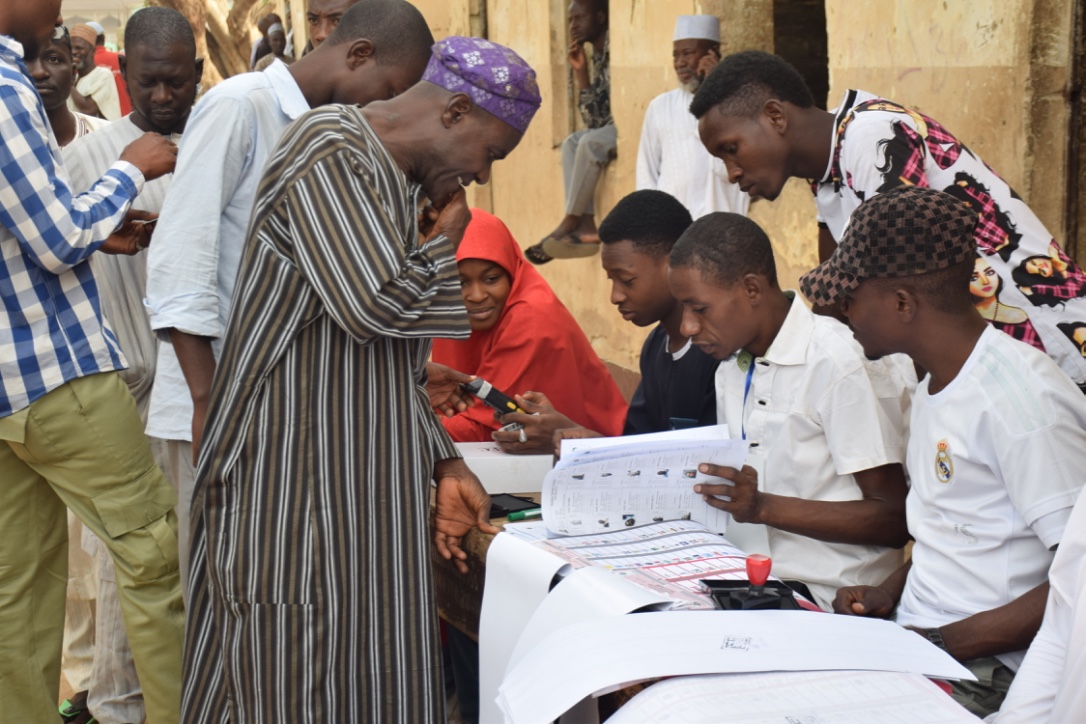

The solution lies in returning power to the people, or put another way, in empowering the people to shun the vicious effect of money in our elections, and in inculcating the value and true spirit of democracy, not in the vain hope that legislating every aspect of our lives will abate the evil. Again, President Buhari points out the obvious. The higher the stakes—and they can’t get higher than our numerous parties conducting direct primaries across the length and breadth of the country—the ever greater the amounts of money that would be needed by the parties to organise them and to fund INEC’s supervision at thousands of locations. And this gives even greater advantage to the money-bags, who invariably are the incumbents: the president, governors, senators and representatives, ministers and other high political appointees running for elective office, state legislators and local government chairpersons. Or the challenger with a godfather or for whom money is no object. Just how would direct primaries prevent a poverty-stricken electorate from selling their votes to the highest bidder? My experience of being universally hailed twice over as head and shoulders above my opponents and yet being told to my face, “But you don’t have money” tells me we are better off with the strict prosecution of electoral offences, especially vote-buying. Just three months ago, I was asked by my party and I gladly agreed to enter the race to fill a vacant seat in the Delta State House of Assembly. I lost because the rival party which has controlled the power and purse of the state since 1999 threw open the treasury to buy votes as its only hope of winning. And win they did, offering an average of four to five thousand naira for a vote, even ten thousand naira in some instances! I reported in my reflections, “Of Bye-elections and the Isoko South Constituency 1 BUY-election,” 23 September 2021, how a mother voted against her son’s and my party, APC, because PDP is where the money is: obe yo igho ro, she had said as a matter of fact, franchise be damned! Indeed, at the rate we are going, a goat might very well win an election if sponsored by any of the major parties ready to outbid its rivals. A hyperbole, I agree, but don’t bet against it.

It seems to me that the almost total condemnation of President Buhari’s withholding of assent to mandatory direct party primaries is borne of a nervous anxiety over the fate of our shabby democracy. Given the trauma of military terror constantly triggered by the stark perversions of elections at every level, our very souls cry out for a modicum of respect for the will of the people, starting with the process of nomination of candidates where parties seem to control all the aces. Why leave our fate in their hands, if they won’t practice the internal democracy that they loudly proclaim in their constitutions and manifestoes when we can compel them by law to be democrats? But can we? Can we legislate the internalisation of the ethos of democracy? I think that the president’s letter shows some of the ways that we give ourselves false assurances of popular participation in an era of money-bag politics.

And this nervous anxiety manifests itself in how ready we are to overlook the blurring of boundaries and to condone or even call for the desecration of first principles while at the same time constantly lamenting that ours is a federation in name only. Because we have lost faith in our ability to organise and compel action for the common good, we look to law as our saviour, a deus ex machina that would enthrone democracy by magically doing away with the win-at-all-cost mentality of electoral office seekers and the corrupted will of an impoverished people. It is why, for instance, INEC has to conduct governorship elections and why we want it to also handle local government elections. Yet, the problem of state independent electoral commissions being mere agents of the state governor and his party can be dealt with by guaranteeing their independence. One way of doing so is to free it of the control of a sitting governor by making its budget an appropriated first line charge. Its autonomy would be further ensured with its members drawn from each registered party (which must pass the test of viability and continued registration after an election), civil society organisations and the bar and bench, the chairperson of the commission to be elected from among the members. This formula, by the way, can also be used to constitute INEC, and the Justice Uwais panel made a gesture towards the same goal. But rather than advocate for this or any other means of ensuring the autonomy and credibility of state electoral commissions, we settle for the easy option of calling in the federal government through INEC to further erode the idea of federalism. Even worse, all the states elect their governors on the same day, except for the disruption caused by the courts, leading to a few states now having to elect their governors on the effective dates of the determining electoral petition judgements. The constant, however, is the role of the federal behemoth.

Which brings me to the thrust of Adegboruwa’s earnest criticism of President Buhari’s refusal of assent and urging of the National Assembly to override it: that mandatory direct primaries do not violate the constitution of the political parties, given the constitutional and statutory duty of INEC to register parties in accordance with the provisions of the constitution which, needless to say, are superior to any validly enacted law, never mind mere party constitutions that are not legal documents in the first place. Unimpeachable argument, but this ignores the question of the extent, scope and implications of the fundamental principle and right to freedom of association. It also elides the related issue of the overreaching nature of the military-imposed 1999 constitution. In another context, I know that Adegboruwa would be even more eloquent about how the 1999 constitution tells a lie against itself by claiming it is we the people who enacted and gave it unto ourselves, and point to how it enables the centre to arrogate to itself virtually every significant right and power of government in the exclusive legislative list, thereby making the states nothing more than glorified administrative units of an imperious centre, the lethal effects of which we see in our unitary state passing off as a federation. Why, the constitution even sets up the state governments, when the obverse ought to be the case—the states setting up the federal government—and provides for the manner of election of its executives and legislators. The unending agitation for a sovereign national conference is caused precisely by the need to draw up a constitution that accords with not only the letter but, more important, the spirit of democracy, especially in a clamorous multi-ethnic nation such as Nigeria.

Advertisement

I repeat: I have myself argued the case for direct party primaries but as an address to the parties themselves. I would now qualify that call with a proviso: when necessary. Political parties, as voluntary associations, should be the judge of when to use consensus, direct or indirect primaries to choose their candidate. The efforts and scarce resources of the federal government are better channelled towards the eradication of the withering effect of money in our politics; in particular, of vote buying at polling units on election day. Yet, direct primaries are only one aspect of the amendment bill. I consider electronic transmission of results from polling units far more crucial to the fate of our fledgeling democracy. To that extent, I am more inclined to agree with Femi Falana, SAN, but on a slightly different ground: that the National Assembly strike out the provision in the bill for mandatory direct primaries, since section 87 of the Electoral Act allows direct or indirect primaries, and pass the entirety of the rest of the amendment bill. Since the president did not adduce any other reason for withholding his assent, it goes without saying that we would then not throw out the baby with the bath water.

Ifowodo is a lawyer, scholar, poet, public commentator and principal partner at Remedium Law Partners. He was the APC candidate in the 11 September 2021 Delta State House of Assembly bye-election.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment