This investigation documents multiple cases of religious intolerance in northern Nigeria, providing insights into whether or not the holy scripture supports the death penalty for blasphemy and the position of the constitution and international frameworks on religious freedom.

Usman* is in his early thirties, a Christian convert, resident of Kano state.

But he currently disguises each time he goes out. This is due to fears that he is still being tracked by persons who accused him of blasphemy.

Before he agreed to be interviewed by The ICIR on May 25, in a suburb town of the state, Usman had used a different phone number to share his location with this reporter.

Advertisement

It was a deliberate move to ensure he was not being set up. Yet, he was willing to meet with the right source, The ICIR reporter, who had visited to document real cases of religious extremism and intolerance in the state.

On arriving at the location, Usman kept a distance of about 200 meters apart, looking sideways, still in doubt.

He appeared as one still battling post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), owing to his horrible encounter in the past.

Advertisement

The ICIR would later discover Usman had suffered religious intolerance and had to relocate from one part of Kano to another.

“Sorry for keeping you waiting and staying this far,” he said, forcing a hard smile yet keeping his distance. “You know I’m just doing this for my safety because of my previous experience.”

Religious intolerance is a big issue in Nigeria. And it is not peculiar to a particular religion. It exists among the three major religions in the country – Christianity, Islam and Traditionalists.

By context, the Brussels-based research institute, the Union of International Association (UIA), described religious intolerance as “the acts denying the right of people of another religious faith to practice and express their beliefs freely.”

Advertisement

The ICIR earlier reported how religious intolerance and extremism resulted in 289 nationwide deaths across churches and mosques between January 2021 and June 2022. And these were from 65 attacks on Churches and 12 episodes on Mosques in the same period.

The genesis of Usman’s nightmares

Usman has a friend named Bello*, a new Christian convert whose decision was vehemently opposed by his (Bello’s) parents. He was threatened severely and, eventually, disowned by his family.

He would later seek refuge in Usman’s house after escaping from his parent’s residence through the roof. Multiple sources confirmed leaving Islam for any other religion is sacrilegious, especially in northern Nigeria.

Bello had to stay with Usman for a few months; unknown to the two, they were being tracked while his parents waited for the right time to strike.

Advertisement

Alas! It came.

It was on a sunny Monday morning towards the end of the lockdown in 2020. Bello needed to correct his bank account information, and both set out that morning to the bank. On approaching the financial institution, they got surrounded by Bello’s parents, relatives, and men dressed in security regalia.

Advertisement

“We were beaten mercilessly,” he told The ICIR. Usman said they sustained injuries.

“While they were beating us up, nobody around could help because they said I was why their son converted to Christianity.”

Advertisement

As he narrates his heart-wrenching story, he unconsciously looks around as one being watched.

“After beating us up like criminals, we were bundled into a tricycle and whisked to a vigilante outpost. We were detained for several hours and handcuffed at the leg as we bled while they went through our phones after forcing us to unlock them.”

Advertisement

He was later taken, with his friend – Bello, to Rijiyar Zaki Divisional Police station, along Bayero University Kano road, Ungogo L.G.A. of the state. “The vigilante officials abused me verbally, said harsh words about my religion, and we were taken to Rijiyar Zaki Police station in the evening.”

The Divisional Police Officer eventually released him.

Other instances of religious intolerance

In June 2015, a Sharia court in Kano sentenced nine persons to death for blasphemy. The victims allegedly rated Sheikh Ibrahim Niasse, a Senegalese Tijaniya sect’s founder, as “bigger than Prophet Muhammad.”

This would ordinarily mean demeaning the superiority of the highly revered Islamic clergy – Prophet Muhammad. But it eventually led to social disorder, and swiftly, judgement was passed over the nine victims – eight men and a woman.

Another cleric, Abduljabbar Kabara, was not so lucky despite being a cleric, and son of the deceased Nasiru Kabara, leader of an Islamic group – Qadariyya Islamic Movement in West Africa.

He was sentenced to death by hanging for blasphemy. The Upper Sharia Court in Kofar Kudu, Kano state, Thursday, December 15, 2022, found him guilty of a four-count charge, including blasphemy.

Umar Farouk, another victim, was also found guilty of blasphemy for reportedly abusing Prophet Mohammed while arguing with his friends. He was a 16-year-old teenager. He also got a-10-year jail term from the Sharia Court, though the judgement was later nullified by a superior court in the state.

The story of the late Deborah Samuel is probably still fresh in the minds of many. She was killed at the Shehu Shagari College of Education in Sokoto state based on the allegation of making a “social media post that blasphemed the Prophet, Muhammad.”

The incident drew global attention, mainly condemnation; the school was closed. It was re-opened shortly after. The ICIR cannot independently confirm if anyone has been prosecuted for the incident. A Nigerian former vice president, Atiku Abubakar, and ex-presidential candidate in the 2023 presidential election had tweeted condemning the mob attack on the female student. But he later reversed his decision. He deleted the Twitter post when he came under attack.

Aminu Ibrahim Daurawa, the former head of Kano state religious and morality police, Hisbah corps, argued that Muslim clerics have agreed that any disrepute with the holy prophet attracts a death sentence.

“There has been the consensus among Muslim scholars that insulting the prophet carries a death sentence,” Daurawa told the B.B.C. Hausa service in June 2015.

“We quickly put them on trial to avoid bloodshed because people were very angry and trying to take the law into their hands.”

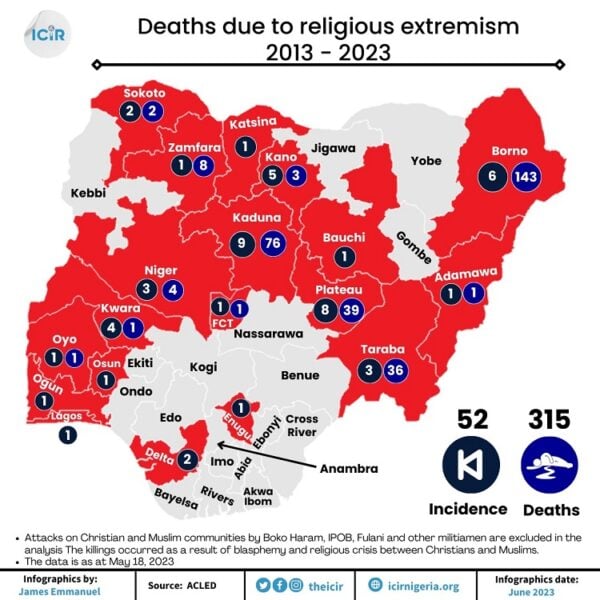

The ICIR, in a recent study of data collected by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), revealed Nigeria witnessed at least 52 incidents of religious attacks, accounting for 315 deaths in a decade, 2013 – 2023. ACLED is a data source that collects all kinds of crisis information with dates, locations, actors and fatalities and makes it freely available to the public. However, the findings in this study focused solely on incidents of blasphemy and religious crisis leading to killings due to intolerance between the two major religions.

Attacks on Christians and Muslim communities by the Boko Haram, IPOB, Herdsmen and other militia groups were excluded.

Death penalty for blasphemy: Right or Wrong?

Nevertheless, there is a mixed reaction to whether or not the Holy Quran supports the death sentence for those accused of blasphemy.

Oyewole Oladipupo, an Islamic scholar at Allahu Wahid Central Mosque, Osogbo in Osun state, said the Holy Book – the Quran does not support capital punishment for blasphemy.

He said the “Quran didn’t support it”. According to him, such capital punishment violates the freedom of religion as documented in the constitution. Yet, he noted the act is a practice in the Islamic faith as not all Islamic laws are written in the Quran but in Hadiths.

Ustaz Abdulafeez Akomolede, the Mudir (Principal) of Al-Mafuz Islamic School, also in Osogbo, shared a deeper perspective. He said the Quran discourages Muslims from leaving the religion for any other, and the act could attract the death penalty.

Akomolede emphasised that those who abused or committed blasphemy against Prophet Muhammad should not be subjected to capital punishment as the Quran does not back it.

The country, he said, is governed by a constitution which supersedes any other law, including the Sharia. But, “if the whole nation decides to run its affairs based on Sharia law, the death penalty applies to anyone who discards Islam for other religion.”

He argued further, citing the instance of the COVID-19 lockdown where the Federal Government, in 2020, asked everyone nationwide to stay indoors to prevent community spread of the disease, “No one dared breach the law.”

On the contrary, the Chief Imam of Nagazi-Uvete Jumu’ah in Okene, Kogi, North Central Nigeria, Imam Gusau Murtadha Muhammad, confirmed the death sentence for anyone who blasphemes against Islam, Prophet Muhammad or any of the prophets.

But he was more specific that the judgement would be done by the right authority, such as the court, not by the mob or any individual.

“The Constitution does not allow you to take laws into your hand. There are courts, leaders…even if someone committed blasphemy, nobody in the society has the right to take the life of another.”

In a recent interview with Wale Fatade, an editor at The Conversation, AbdulRazzaq Alaro, a Professor of Islamic Law at the University of Ilorin, Kwara State, described blasphemy as an offence under the Sharia law and Nigeria’s criminal law.

He argued the capital punishment for blasphemy stressing its recognition to the supreme court.

According to Alaro, the apex court recognised blasphemy as a Sharia offence and described it as “a serious crime which is punishable by death….”

In the referenced case heard on Friday, 15 February 2008, the appellant was criticised for taking the law into his hands by ‘slaughtering’ the victim “like a goat”. The proceeding was before five Justices of the Supreme Court. They are Justices Niki Tobi, Sunday Akinola Akintan, Walter Samuel Onnoghen, Ibrahim Tanko Muhammad (the immediate past CJN) and Christopher Mitchell Chukwuma-Eneh.

Incidentally, the issue of blasphemy is not peculiar to Nigeria. It is a reality in other countries, including Islamic nations such as Pakistan, where a Christian mother of four bagged a death sentence for alleged blasphemy, Iran Algeria, to mention a few.

In 2019, the U.S. government labelled Nigeria one of the most religiously intolerant countries globally.

The FG was not pleased with the report, and the former minister of information and culture, Lai Mohammed, countered the declaration.

A year after, the U.S. delisted Nigeria from the controversial list. Still, several documented reports confirmed incidents of religious intolerance persisted. A recent example was the case of a multimillion-naira monument demolished by the Kano state government because it allegedly had a large Christian cross.

At least, in two quarters of 2022, the nation experienced incidents depicting one form of religious extremism or intolerance. These events have cast aspersions on the supremacy of the nation’s Constitution on religious freedom.

Nigerian Constitution and dynamics of religious freedom

In Nigeria, the freedom of religion is enshrined in the Constitution as a natural right, just as the freedom of expression. It is similar to Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and Article 91 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights which Nigeria is a signatory.

Chapter 4, Section 38 of the Constitution also promotes rights to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.

“Every person shall be entitled to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, including the freedom to change his religious belief, and freedom (either alone or in community with others, and in public or in private) to manifest and propagate his religion or belief in worship, teaching, practice and observance.”

The same Constitution, in Chapter 1, Part II, Section 10, prohibits adopting a particular religion by state or federal governments.

It states that “the Government of the Federation or a State shall not adopt any religion as State Religion.” That implies no state in Nigeria, even the federal government, can adopt a religion.

While it is worth noting that state governments have the right to enact laws that could govern their activities, legal experts argue the Constitution remains supreme.

Nevertheless, for many, these situations have raised some curiosity, from the enactment of Sharia law, through the adoption of Islam in some 12 northern states, to the prosecution of teenage boy and death sentences for blasphemy.

Some would argue that these realities countered the religious freedom guaranteed by the Constitution. Others have also debated that the series of events indirectly implied a battle of supremacy between the Constitution and the Sharia law.

In a paper published on the Nigerian Law Forum, titled, The Islamic Legal Account on Justification of Death Penalty for Blasphemy Against the Holy Prophet (S.A.W.), N.U Muhammad, the author, insisted that blasphemy would always attract the “unquestionable punishment of death.”

He referenced the former Justice of the Supreme Court of Nigeria, Ibrahim Tanko Muhammad, to validate his position.

According to him, Tanko “puts it clearly and pronounced it in a case of Kaza vs State, (2008)7 NWLR part 1085 page 125, particularly at page 199 para A-B: the trite position of law under Shari’a is that, any Sane and Adult. Muslim who insults defames or utters words or acts capable of bringing into disrepute, odium, contempt, the person of the holy prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.), such a person has committed a serious crime punishable by death.”

“It is clear that the Supreme Court of Nigeria has affirmed the punishment of death for the offence of blasphemy in the Case as mentioned above and leaves no doubt in the mind of Nigerians,” he argued.

But, Alaro stressed that even if blasphemy should attract a death sentence, it “has to be established through evidence before a court of law” and “the killing is controlled and sanctioned by the authorities.”

In his opinion, another lawyer, Abiola Kolawole, said the 1999 Constitution “is supreme to any other laws, acts and decrees.” He explained to The ICIR that the accused must rely on the constitution in the case of blasphemy.

“The reason why these things keep going on is the fact that they only use sharia laws in the north to intimidate people.”

“In the instant case, that practice will take the second chair if it comes close to the constitution. When those persons decide to defend themselves, they will have to use the Constitution.”

Barrister Ezra Gana, in his opinion, believed under the Sharia law, it is an offence to leave Islam for other religions, but the constitution does not support it. He argued Nigerians are free to choose any religion, describing such a scenario as a ‘conflict of laws,’ which only the court can decide at the time of the incident.

Regardless, Gana said there is currently no judgment in the country that penalised any Nigerian for changing his religion. Still, he emphasised that usually, before persons accused of such acts are taken to court, there would have been a mob action – killing the victims.

“It does not get to court for interpretation…”

“I know of a Christian girl that converted to Islam, and they cited those laws, and it was upheld, but the other way around, a Muslim being converted, I don’t think the law usually relates to such. That’s where the problem is.”

Blasphemy, the recurring accusation

In August 2020, a musician, Yahaya Sharif-Aminu (22), was sentenced to death for sharing a song alleged to be blasphemous via WhatsApp. The song was said to have contained profane content. He was sent on retrial and continued arguing his case at the Supreme Court.

The argument remains that the blasphemy law in Kano State’s Sharia law violates the nation’s Constitution and other international agreements on freedom of human rights, of which Nigeria is a signatory.

When he was arrested, Mubarak Bala was the President of the Humanist Association of Nigeria. His case was particularly interesting because his father was an Islamic cleric.

There was a notable Muslim family in Kano State. That means his entire household was Muslim and expected to be devout, but he became an atheist and a humanist who was vocal about his sentiments against religion. He was charged with blasphemy – insulting the Prophet Mohammed. Bala was accused of making public assertions via his Facebook post, capable of causing “a breach of public peace.” The controversial post would later land him a 24-year jail term.

Since Sharia was re-launched in Gusau, the state capital of Zamfara State, on October 27, 1999, it has extended to 11 other states. They include Bauchi, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Borno, Yobe, Gombe, Sokoto, Kaduna, Jigawa, and Niger.

The criminal and Penal Code dimension

The Criminal Code Act and the Penal Code also govern Nigerians. While the southern part of the country adopted the Criminal Code, the north embraced the Penal Code.

Both codes are to prevent social vices or criminalities. And blasphemy is considered a criminal offence in both laws but not part of the Constitution. Still, experts say the codes derived their strength from the constitution.

“Every state has the right to make laws according to their culture or tradition. That is why you see the Chieftaincy law of Kogi state or that of Ogun state…,” Kolawole explained while reacting to the criminal and penal codes.

He went further – “The idea behind these penal codes and criminal codes is that, I chose to drive in my house in a particular way, you can choose a different approach in your house, but at the same time, when we go out, we have to obey Federal Road Safety Law.”

The whole of Sections 204 to 213, Chapter 19 of the Criminal Code Act, for instance, documents sanctions for wrongdoings against religious worship. It forbids any act of publicly insulting any religion.

Section 204 of the Criminal Code speaks explicitly to when an individual insults a religion – irrespective of Christian, Islamic or traditional practices. And the maximum punishment an offender could attract is a charge for a misdemeanour or two years imprisonment.

“Any person who does an act which any class of persons consider as a public insult on their religion, with the intention that they should consider the act such an insult, and any person who does an unlawful act with the knowledge that any class of persons will consider it such an insult, is guilty of a misdemeanour and is liable to imprisonment for two years,” it reads.

By extension, Chapter 20 of the criminal code deals with Witchcraft, Juju, Ordeal and Criminal Charms.

Only using charms for criminal activity attracts the highest sanction of five years.

These implied no part of the criminal code regulating offences related to religious worship supports the death sentence. But, according to the Berkley Centre for Religious, Peace and World Affairs, the Sharia law, which is a creation of the states, “is exclusively concerned with acts considered to insulting Muslims, the punishment which can be as severe as execution.”

The ICIR contacted the Police to understand how issues of blasphemy are treated. But in his reaction, Olumuyiwa Oladunmoye, the Force Public Relations Office (FPRO) Assistant Commissioner of Police (ACP), no Nigerian has the right to take the life of another, as it would amount to jungle justice, which is against the law.

The Police spokesperson explained that in such a situation, the Police try to prevent lynching.

“We do our best to prevent it, but when we can’t, we go after the perpetrators.”

“It is a jungle justice case, treated like a jungle justice matter. Go through our records; many of them are presently being prosecuted. We don’t encourage jungle justice.” He advised that anyone who commits any offence should be handed over to the police.

Here is an example of the Kano state penal code and Lagos state criminal code.

Bello in six-week detention at vigilante’s custody

Being a Christian convert is perhaps one of the toughest decisions someone born into a Muslim family can make. This is because it often comes with severe consequences.

It could be worse in Northern Nigeria. Observance that a Muslim fails to observe his regular prayers will often call for suspicion. In the case of Bello, who converted to Christianity, he has been a great friend of Usman for years, such that they have crossed several hurdles together.

When Usman contacted Bello at the vigilante detention, he said he had spent over three weeks at the holding.

The ICIR attempted to verify the detention period. And in his response, Bello put the holding period at “one month and two weeks.” He confirmed he escaped from his father’s house through the roof but was uncomfortable speaking further.

“He looked starved and emaciated,” Usman told The ICIR during the visit. “Every Friday, they took him to a Hisbah office for cleansing to retrieve him back to his previous religion.”

*Information on how Usman left the vigilante holding is withheld for security reasons.

When Bello relocated to another state, he sought refuge and underwent a discipleship programme in a church since he was still keen on remaining a Christian.

“When he escaped, and his whereabouts were unknown, his family members and other relatives kept threatening me several times via phone calls, so I did not feel safe.

“When he returned after some months, his parents never allowed him back to the family because they had already disowned him. He now stays with his uncle, who can tolerate him.”

“To date, I do not follow regular routes to work or pick up calls from unknown phone numbers because those threats keep coming in”, he explained that he *finds innovative ways to stay hidden.

“That’s why I also took those measures before we met at the roadside.” He told The ICIR.

Living as a frustrated Hausa Christian

In 2022, Usman had what he described as a terrible experience when he relocated to a new neighbourhood in another LGA in Kano state.

He rented a room for N60,000, but barely a week after settling in; he started experiencing discrimination from a neighbour who found out he was a Hausa Christian from Kano. The neighbour informed the community and ward head. This led to Usman being interrogated at different times, which he described as quite frustrating.

“On a particular day, two men came to my room and said they were sent by the ward head to investigate the people who newly occupied the space and demanded that the room key be given to them. I refused to give them the key, and they left in annoyance.

“As if that was not enough, they kept harassing me by barging into my room at different times to interrogate me and never gave me peace of mind. Days later, the landlord called me and told me that my rent had been increased to N80,000,” he told The ICIR during the visit.

“I refused to pay the increment, and we kept having back and forth. It was so bad that the caretaker and the landlord had an issue because while the landlord was frustrating me, the caretaker tried his best to stand up for me because I was unjustly treated.”

“It got to a time that the landlord asked me to park out of the house, stating that he wants to renovate it, so I had no other option than to leave.”

Victimised by family members

When Ibrahim* was little, he stayed with his mother in Edo State. His mother is a Christian, while his father, a resident of Kaduna, is Muslim. At age five, he was later taken away from his mother to Kaduna state, and he started attending Islamic school and practising Islam.

Almost two decades later, he suddenly stopped attending the regular Muslim prayers. He converted to Christianity but never told anyone.

“One of my uncles noticed I no longer observed the Muslim prayers. He confronted me and warned should there be religious crises in the state; I would never escape it.”

The hostility against him grew, he told The ICIR, and he moved to another state. But, even at that, he said he would always watch his back and peep through the window each time he spoke about religion.

In 2015, Ayuba Hassan, a Christian Fulani from Kano, recalled how a shopkeeper in his community never sold confectionaries to him or any of his family members, all because of their religious beliefs.

At first, Hassan thought the shopkeeper did not just like his family, but afterwards, he understood that the shopkeeper only sold groceries to individuals who were Muslims.

As this lingered, the shopkeeper later said he doesn’t sell groceries to people he described as ‘Arna’ (A Hausa word for pagan).

“He told us that he would not sell provisions to us because, according to him, we are Pagans, but I am a Christian and not a Pagan. No matter how often we go to his shop, he never sold provisions to us and others he knew were Christians,” he said.

But to end religious extremism and intolerance, Akomolede, the Mudir of Al-Maruz Islamic School, advised not every battle should be fought on behalf of the holy prophet or God, as whoever commits blasphemy would definitely be judged on the last day – the judgement day believed by many faiths.

He advised peaceful and religious tolerance, stressing that the nation’s Constitution should be supreme above all and being mindful of different religions practised in the country.

“We have a constitution in Nigeria. Leave judgment to God,” he suggested. “Those who abused the Holy Prophet or left Islam for other religion should be left for God to judge.”

“Even if you arrest a robber, and he is presented to the Police, and the next day you see him walking freely on the road, leave judgment to God.”

NOTE: Names, places, and information with asterisks were deliberately omitted or changed for security reasons.

This story was produced with the support of the International Centre for Journalists (ICFJ) in partnership with Code for Africa.

Add a comment