BY MOSUNMOLA ADEOJO

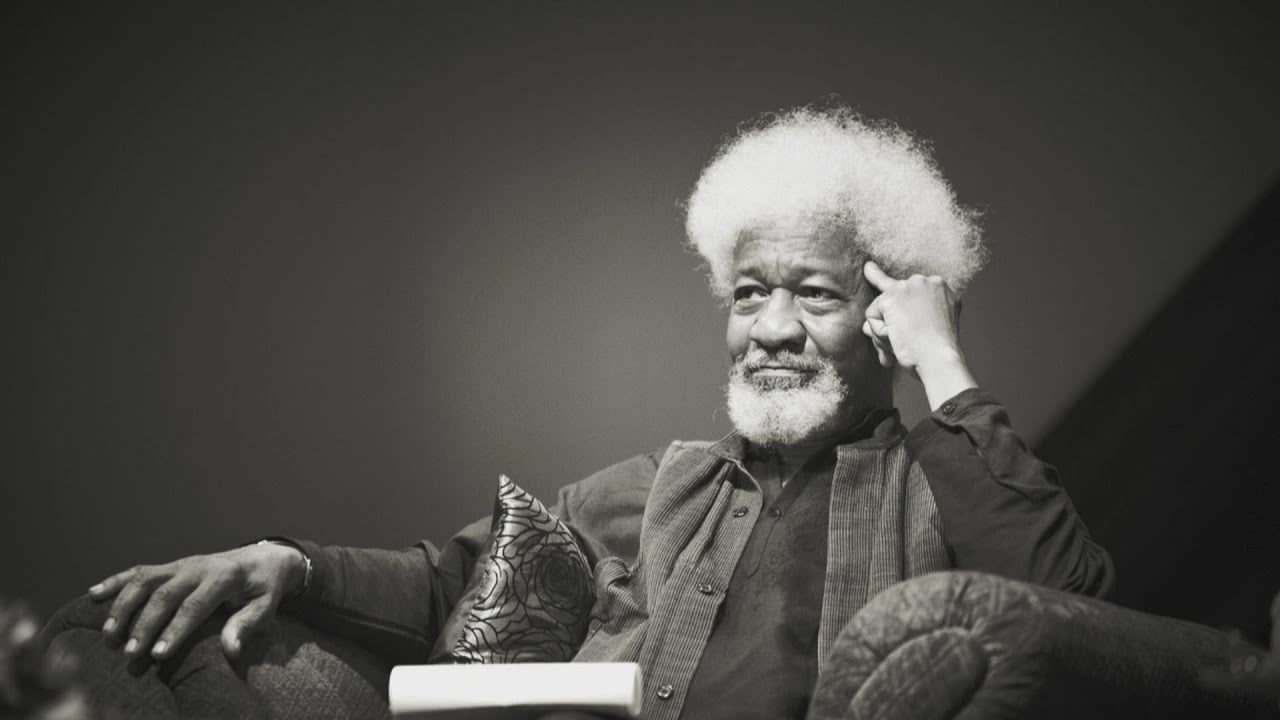

In this gripping documentary, Ebrohimie Road: A Museum of Memory, Olongo Africa invites us on an intimate journey through time and space, centered around Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka’s former residence at the University of Ibadan. Skillfully written and directed by Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún, with Tunde Kelani’s captivating cinematography, this film transcends mere documentation to become a poetic exploration of memory, family, and the enduring marks we leave on the spaces we inhabit.

The documentary starts in October 1967, and we’re immediately thrust into a Nigeria grappling with the aftershocks of coups that had rattled its nascent independence and echoes of a civil war that began three months before. This historical framing serves as more than just context; it is a poignant reminder of the tumultuous backdrop against which Soyinka’s domestic life unfolded. In addition, juxtaposing archival footage with contemporary aerial views of the Ebrohimie residence creates a visual dialogue between past and present, setting the stage for the film’s central theme: the fluidity and fragility of memory.

The film’s power lies in its kaleidoscopic approach to storytelling. We hear from Soyinka’s daughters, whose childhood memories vividly depict a home alive with creativity and warmth. Their recollections of carvings and sculptures – mysterious to visitors but utterly ordinary to them – offer a touching glimpse into the everyday magic of growing up in the shadow of a literary giant. These intimate portraits reveal Soyinka not just as the fierce intellectual and activist the world knows but as a father whose passions and eccentricities colored his children’s world in unforgettable ways.

Advertisement

We also encounter Soyinka’s passionate attachment to his home on Ebrohimie Road when he passionately explains how he got his wooded residence. “I not only chose it. I campaigned for it. I lobbied for it. I cheated for it. I beat people up for it. To make sure I had that particular house. Anything it took” (Ebrohimie Road). This anecdote, delivered with Soyinka’s characteristic blend of intensity and wry humor, speaks volumes about the significance of place in the life of a man known for his restless intellect and activist spirit. It’s a testament to how deeply our environments shape us, becoming extensions of ourselves.

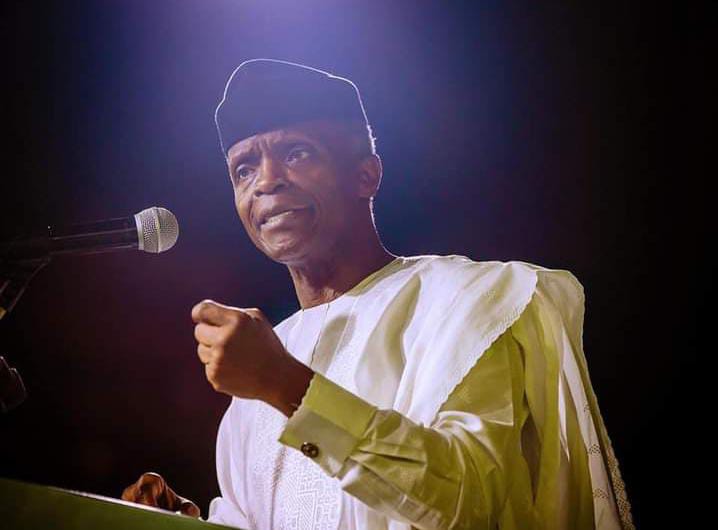

Prof. Fashina, the current occupant, adds another layer to this rich tapestry of the residence’s deep significance. With evident pride, Fashina welcomes us into what he reverently calls the “Soyinka House,” later recreating an iconic moment as he poses on the steps, mirroring Wole Soyinka’s 1969 post-prison photograph after an interview from the Daily Times. This visual echo, combined with Fashina’s profound pride, bridges past and present, highlighting the enduring legacy of the man (Soyinka) and the space he once called home. This moment in the film is a poignant reminder of how places can hold onto the essence of those who have passed through them, becoming repositories of history long after their original inhabitants have moved on.

Yet, amidst these layers of fond recollections and enduring legacy, the documentary touches upon a moving counterpoint: Soyinka’s reluctance to revisit Ebrohimie Road. As hinted at in the film, this refusal speaks volumes about the complex nature of memory and its power to comfort and wound. For Soyinka, the house is not just a repository of happy family moments and creative inspirations but also a keeper of painful memories. The film delicately suggests that these painful associations might be linked to Soyinka’s time in prison and the tumultuous political climate of the era.

Advertisement

Soyinka’s brief return to Ebrohimie Road after his 27-month imprisonment, followed by his self-imposed exile, suggests the emotional toll of revisiting this once-cherished space. The documentary subtly conveys how the home, once a sanctuary, became intertwined with painful memories of his incarceration and the turbulent political climate of the time. Soyinka’s absence from the physical revisiting of space adds a layer of complexity to the narrative, reminding us that places can hold both light and shadow in our memories. It starkly contrasts the warmth with which his family members recall the house, highlighting how the same space can hold vastly different meanings for different individuals, even within the same family.

This part of the documentary is a powerful reminder of the deeply personal nature of our connections to place. It invites us to see how spaces become intertwined with our life experiences, sometimes to the point where revisiting them becomes too emotionally charged. Soyinka’s refusal to return physically while still engaging with the memory of the place offers a nuanced exploration of how we navigate our personal histories and the spaces that have shaped us.

The film also focuses on the bittersweet nature of memory and the relentless march of time. A neighbor’s roll call of former residents who are now deceased reminds us of Derek Walcott’s lament in his poem “Half of My Friends are Dead.” Life and time’s transience are further emphasized by the physical changes to the house and its surroundings over the years. As shown to Soyinka himself, the once-spacious grounds seem to contract, with encroaching development and repurposing of land gradually diminishing the expansive, wooded haven he once knew. Such a transformation illustrates how the passage of time and changing resource needs can alter even our most cherished spaces. In addition, the themes of memory, time, and fragility are further explored through Soyinka’s misremembering of the location where the 1969 post-prison photograph was taken. This moment in the documentary serves as a gentle reminder of how even our most cherished memories can play tricks on us due to time and distance.

Ebrohimie Road is more than just a documentary; it is a living, breathing archive of memories. By weaving together voices from family members, neighbors, colleagues, and former students, the documentary creates a rich, multifaceted portrait of Soyinka and the house that played such a central role in his life. Each perspective adds depth and nuance to our understanding, from the brother-in-law’s reminiscences to his ex-wife’s encounter with the new occupants. In the end, the documentary stands as a powerful meditation on the intertwining of space, memory, and identity. It reminds us that the places we call home are not mere backdrops to our lives but active participants in shaping our experiences and preserving our histories. In an age of fleeting digital memorialization and constant change, this documentary underscores the crucial role that tangible spaces play in anchoring our memories and connecting us to our past.

Advertisement

As the final frames fade, we are left with a profound appreciation for Soyinka’s residence on Ebrohimie Road as more than just an address. It emerges as a symbol of memory, a physical manifestation of the stories, struggles, and joys of all who have passed through its doors. The film challenges us to consider the spaces in our lives that serve as repositories of memory, reminding us that we preserve a part of ourselves and our shared history by protecting these places. In doing so, it reaffirms the importance of space and location in crafting memories and keeping them alive for generations to come.