BY DEMILADE OSOTEKU

The 2018 Gubernatorial election for Ekiti state was conducted on July 14, 2017, with Kayode Fayemi, the candidate of the All Progressive Congress (APC) winning the election ahead of Kolapo Olusola (Eleka) the incumbent deputy governor of the PDP.

The election was particularly tensed as the theatrics of the outgoing governor Ayodele Fayose with claims of intimidation was met by the allegations of electoral malpractice from the two leading parties and independent observers. A lot more drama may be expected to unfold in the days leading to the hand-over of the reins of control of Ekiti state to Fayemi, an ex-governor. The Fayemi-Fayose-Fayemi cycle has now been completed.

Beyond the usual APC won PDP lost, there are key insights from the election data that are beneficial to the better understanding of the Ekiti elections for those interested in the politics of the state and Nigeria in general. There are also several unanswered questions that the data cannot provide just yet. This article takes a brief look into summary data from the elections on an LGA-by-LGA level and draws key insights with a focus on voter registration, turnout and winning margins.

Advertisement

Voter Registration and Voter turnout

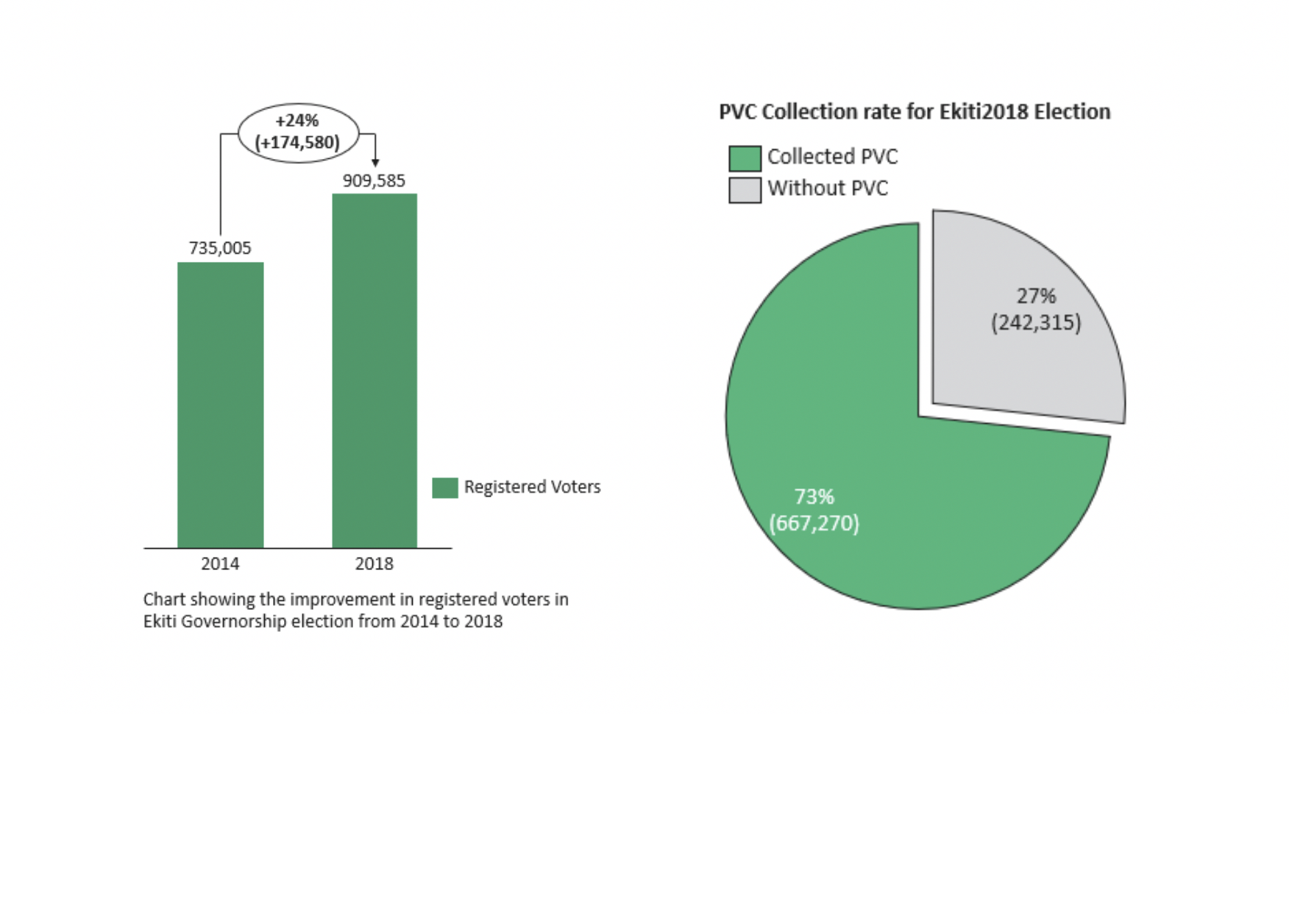

According to INEC 909,585 people registered to vote in the election, representing the addition of 174,580 (24%) people to the Ekiti voters register, compared to the number of registered voters in the 2014 governorship election and the 2015 presidential election. The addition to the voter register during the period represents 98% of the total number of valid votes cast for the PDP in the 2018 elections and is higher than the 120,000 votes that the APC got in the 2014 election. If the voter registration is as tamperproof as it appears, people are increasingly eager to take part in the voting for their candidate of choice. Although it is difficult to draw a direct link that the new addition to the voter register voted for either APC/PDP or any other party, it can safely be suggested that there has been an increased willingness of Nigerians to participate in the electoral process.

A key insight from the voter registration data is the need for a clear procedure for taking dead people off the voter register. This may not be a big problem currently, but, it may be a loophole that could be exploited for unfair political advantage in the future.

Advertisement

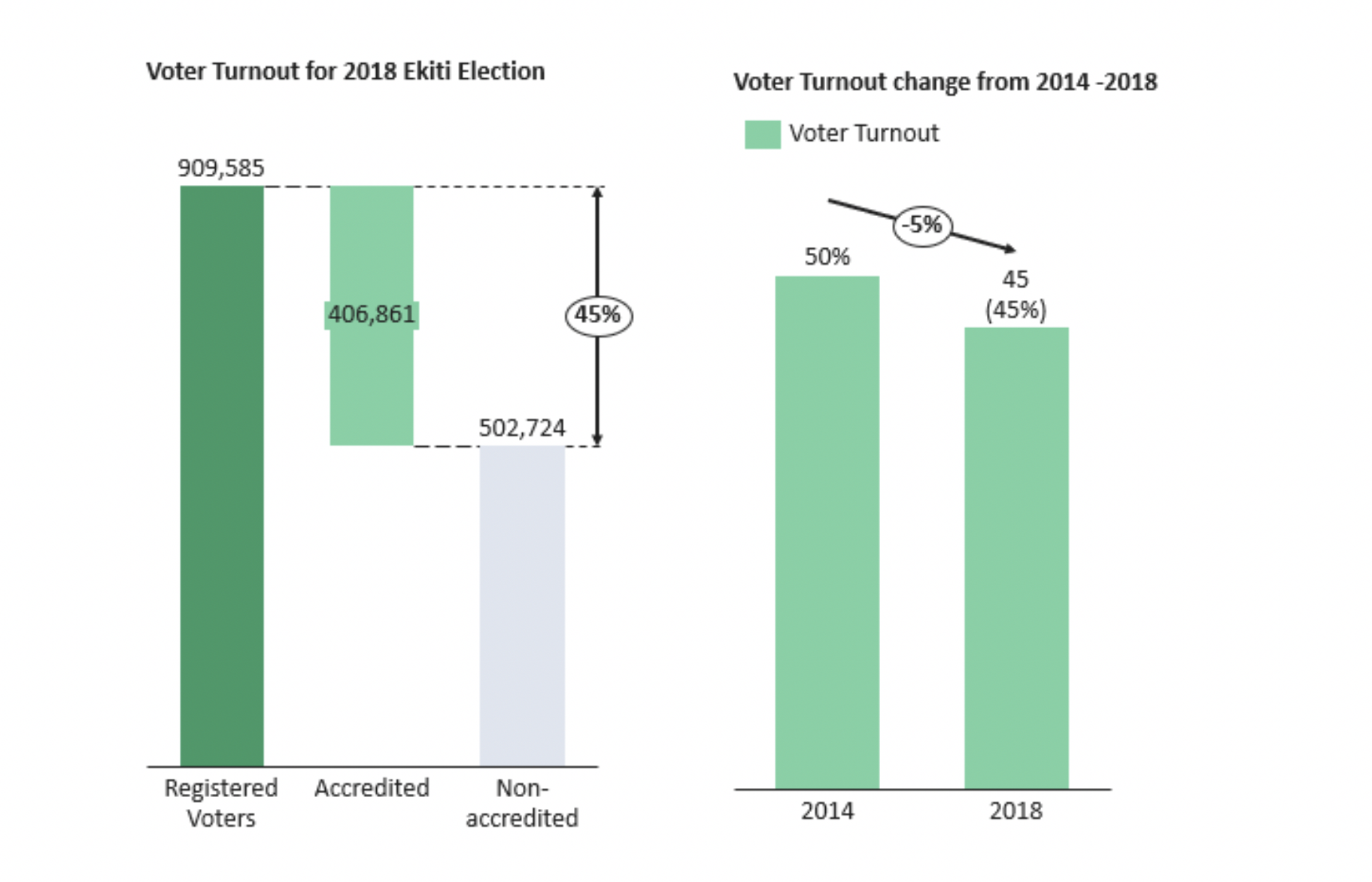

Despite the progress made with voter registration, a twin challenge persists. On one hand, only 73% of registered voters picked their permanent voters card (PVC), while on the other hand, only 45% of registered voters turned out for the election. Why did people who took the pain of register to participate in elections refuse to pick their voter’s card? Is it a problem of political apathy of electorates or is the challenge around the process of PVC collection? These are the kind of questions that need objective answers beyond rhetoric, but the data needed to answer them are largely unavailable.

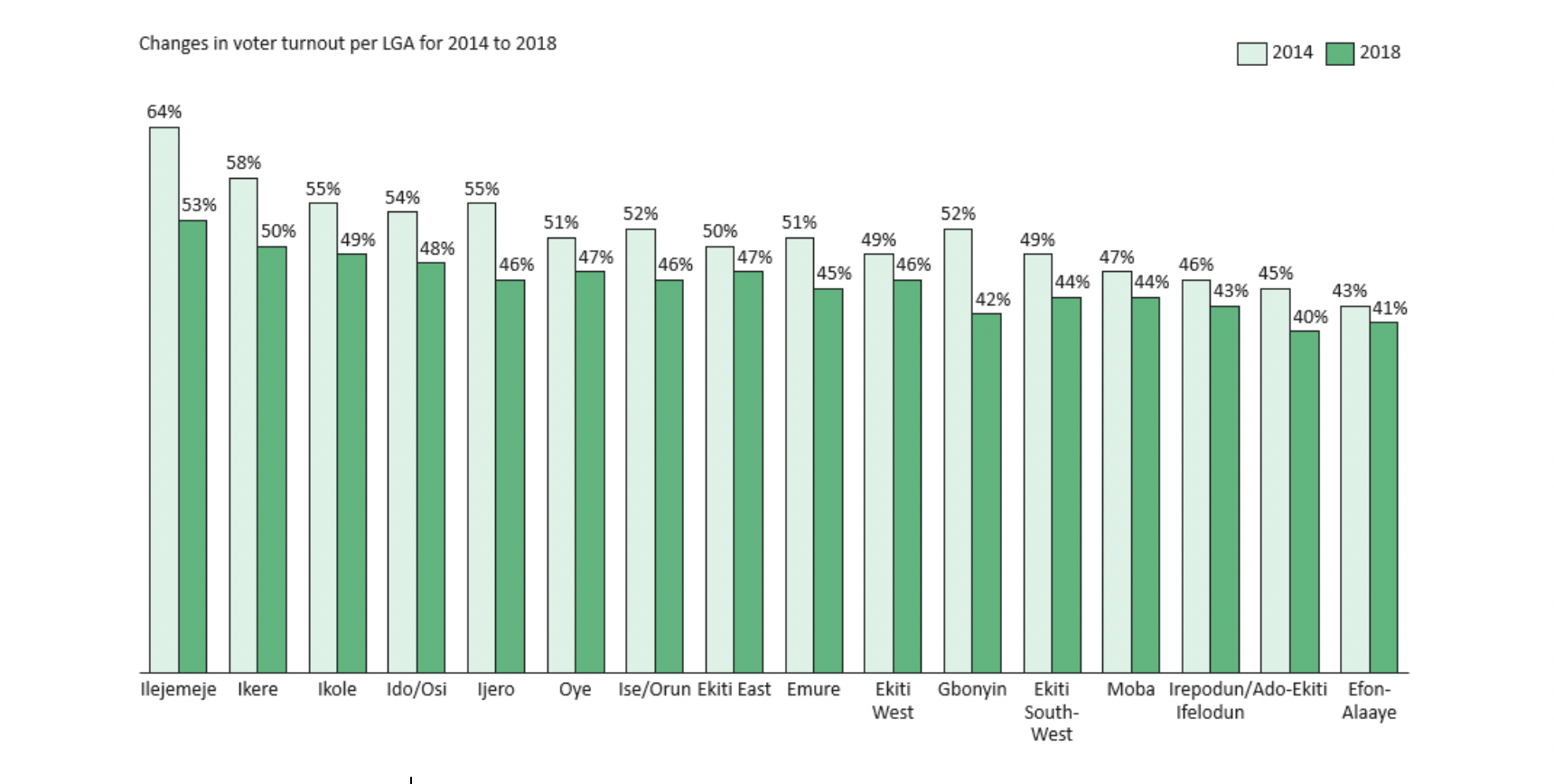

Although voter registration climbed by 24% from 2014, the percentage of registered voters that turned out to be accredited fell from 50% in 2014 to 45% in 2018. Clearly, there are leakages of political capital along the electoral process. Only two Local Government areas in the state (Ilejemeje and Ikere LGAs), had turnout above 50% in the 2018 polls, with Ilejemeje having 53% and Ikere having 50%. Ado-Ekiti the state capital had the lowest voter turnout of all LGAs in the state with 40% of registered voters being accredited for the election. The voter turnout is especially worrying when compared on an LGA-by-LGA basis to the 2014 polls when 10 of the 16 LGAs in the state achieved over 50% voter turnout, with Ilejemeji and Ikere LGAs with leading voter turnout of 64% and 58% respectively. How come more people registered to vote but less of them turned out to be accredited for the election? The puzzle continues.

However, there is a slight beacon of light with respect to voter turnout that we could be somehow excited about. 61% of those who have collected their PVC turned out to be accredited for the election, a term we could call the adjusted voter turn out. The adjusted voter turnout represents the proportion of people with the requisite voting tool (the permanent voter’s card in the case of Nigeria) who were accredited to vote in an election.

Advertisement

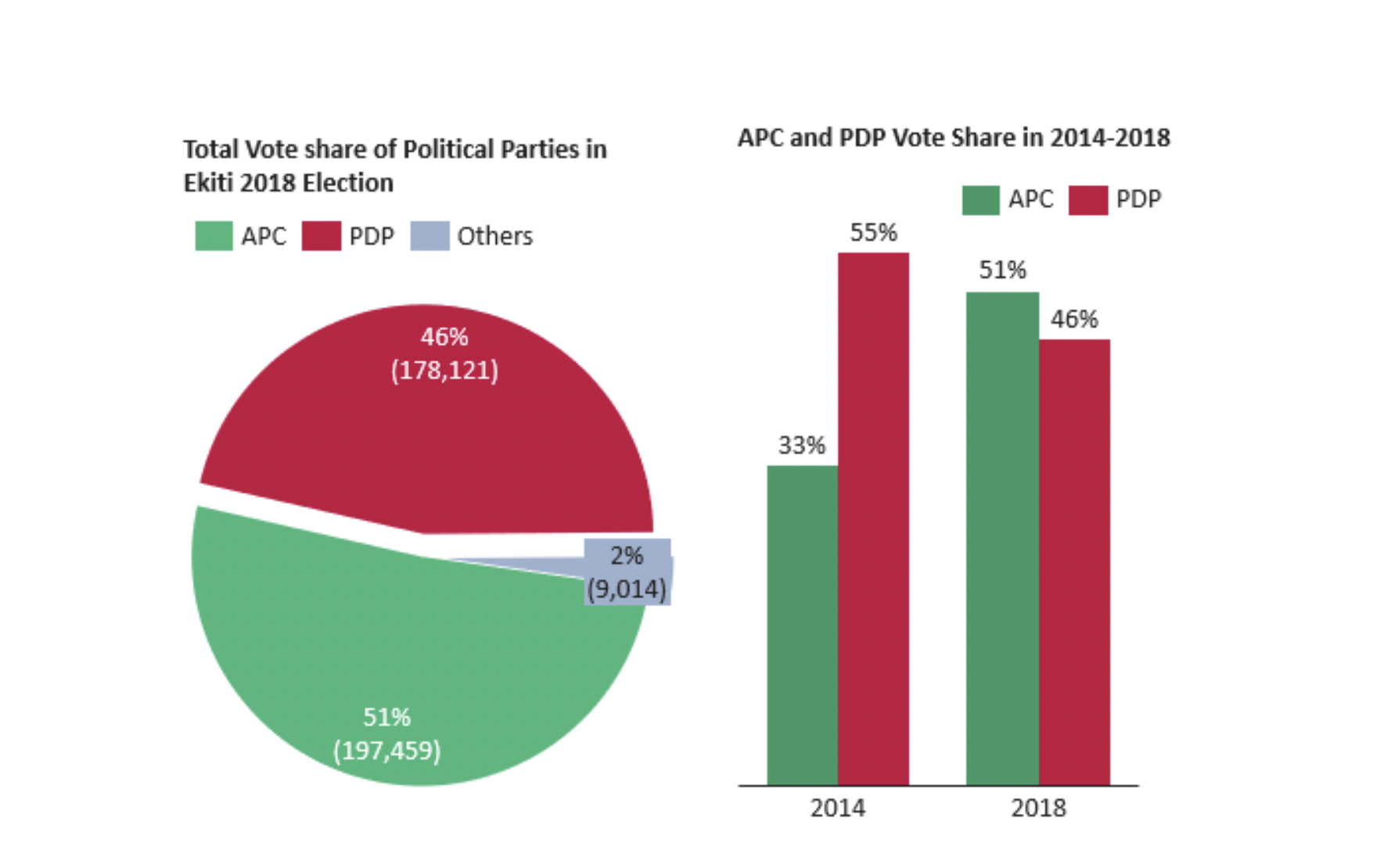

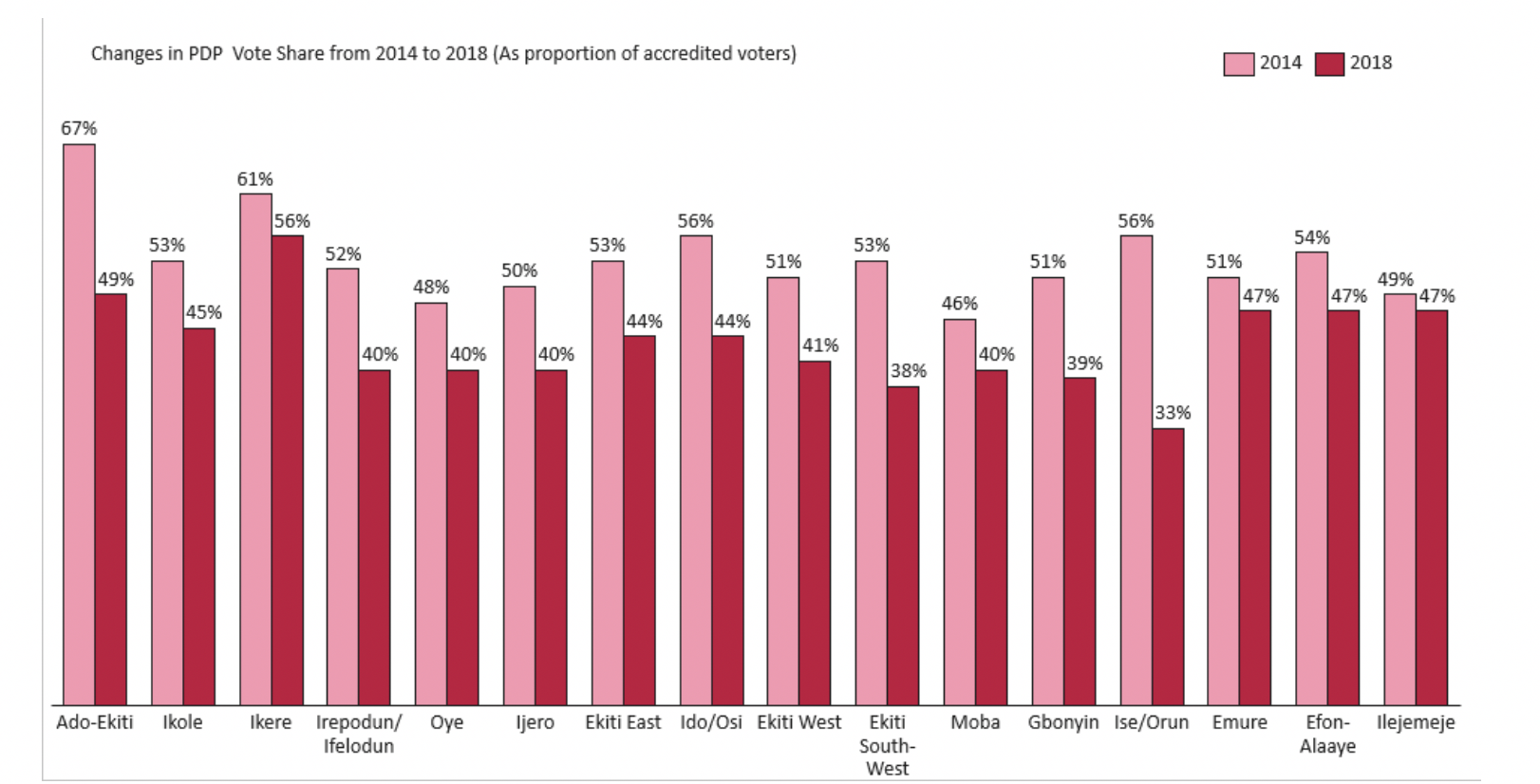

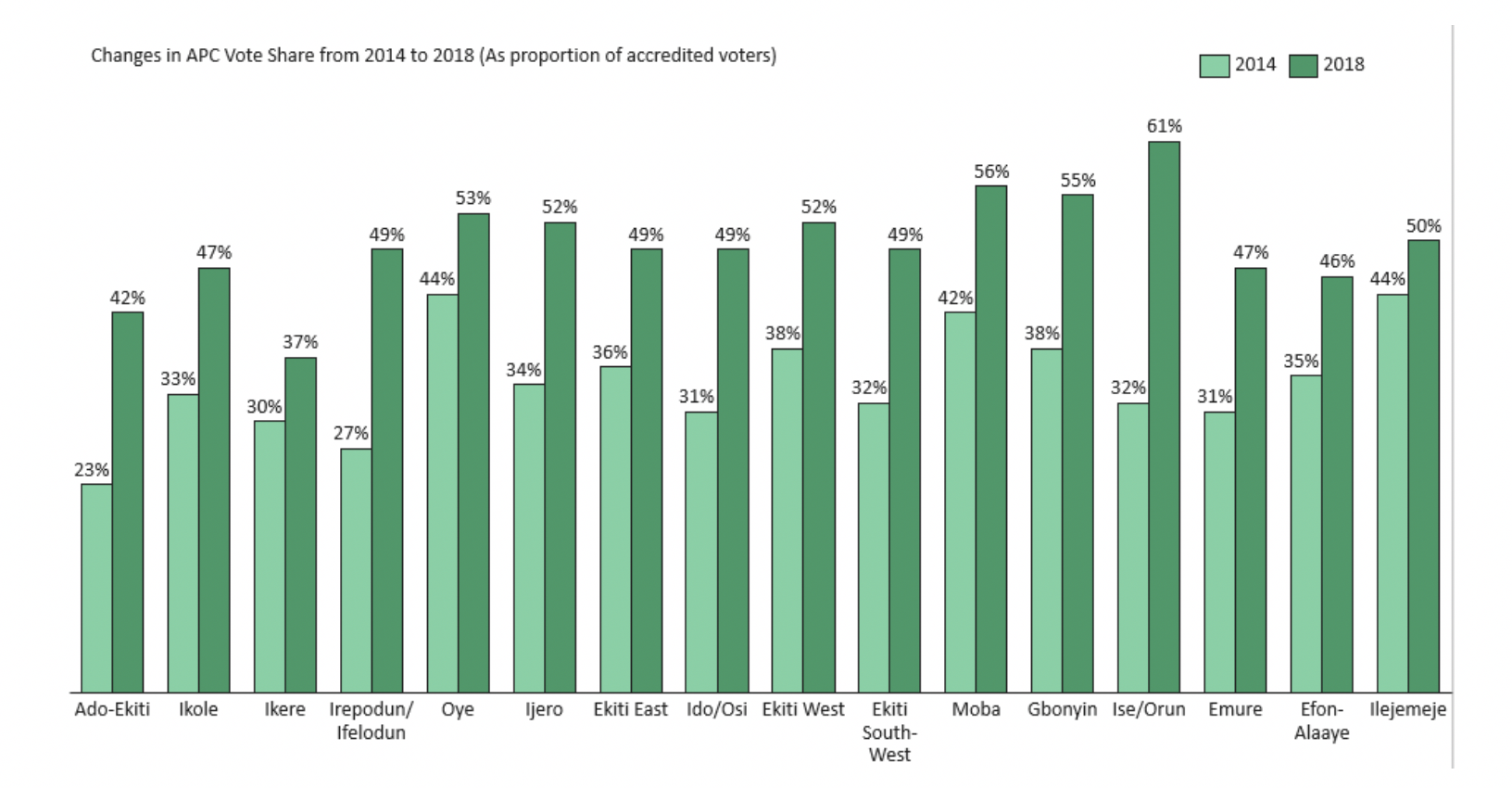

How the PDP lost Ekiti

The vote share of the PDP tumbled from 55% of valid votes cast in the 2014 elections to 46% of valid votes in the 2018 election, while the APC vote share increased from 33% in 2014 to 51% in 2018. The PDP biggest loses were in Ise/Orun, Ado-Ekiti, and Ekiti South-West LGA where the PDP vote share declined by 24%, 18% and 15% respectively. The least vote share change was observed in Ilemejeje, Emure, and Ikere LGAs where only 2%, 4%, and 5% of the PDP vote share was lost. There was no single LGA where the vote share of the PDP did not decline compared to the 2014 election, and the loss was greater than 10% in 8 LGAs.

The APC, on the other hand, gained a lot of ground especially in Ise/Orun and Irepodun/Ifelodun LGAs where the APC vote share increased by 29% and 22% respectively. The APC had a vote share improvement of 10% or more in 14 of the 16 LGAs in the state.

Advertisement

Only 19,388 votes, an equivalence of 4.8% of accredited voters separated the winner from the first runner-up. Judging from the margins alone, this was a very tightly contested election. The PDP won the aggregate votes in 4 LGAs, a decline from all 16 LGAs in 2014. The PDP led with 5,668 votes in Ikere LGA and 4,699 in Ado-Ekiti, but a paltry 162 and 73 in Efon Alaye and Emure LGAs respectively. A vote margin of 73 is perhaps the closest winning margin of a gubernatorial election for an LGA (There may be closer margins but election data are not publicly available for gubernatorial elections, more needs to be done). The APC, on the other hand, won with a margin of 5,611 in Ise/Orun LGA, and above 3,000 votes in Oye, Gbonyin, Moba, and Ijero LGAs.

Advertisement

How might the election result have changed

A higher voter turnout may have increased the competitiveness of the election and better delineated the will of the people from the noise at the margins. A 4.8% margin in a more functional democracy suggests that the policies and principles of both leading parties matter to the electorate and a blend of both sides is the ideal offering the eventual winner should put forward. But in Nigeria’s winner-take-all politics, the 44% of people will have their say but 49% of people will have their way.

Advertisement

The political parties need to work harder in subsequent elections to ensure that registered voters collect their PVCs and turnout for the election especially in urban areas where the big numbers are. The continuous orientation of the electorate on the need to participate in the electoral process improved security during elections without crossing the line of political intimidation are suggestions that can be useful. However, we know so little ‘beyond wild opinions’ on the reasons why the electorate don’t register to vote, why some who register to vote do not get their PVCs, why some who get their PVCs do not make it to the accreditation point on the election day. There is also so consistently collected data on all important election data during live election reporting. For example, the total number of valid votes cast was omitted in many LGAs by many media organizations and interested observers providing live updates on the election.

There are a few things that can be done to improve the understanding of elections in Nigeria. The Independent National Electoral Commission needs to continue to innovate in ensuring complete validated result are uploaded using their social media presence as soon as they are available. Media organizations, civil society organizations and independent observers also need to provide the same information to further strengthen advances in the Nigerian electoral process. Political science academics across Nigerian universities need to show more vested interest in understanding elections better through an ‘Academic situation room’ of some sort. This can provide unbiased independent analysis of elections and critical issues associated with its conduct in Nigeria.

Advertisement

There are still too many puzzles in the objective understanding of electoral politics in Nigeria. The effectiveness of social media, the effect of sharing food items or money before the election, the effect of religious or ethnic cleavages within states and many more salient questions are still at best fuzzy in Nigeria. A systematic collection of electoral data, unbiased scientifically rigorous analysis of electoral trends and an open-source electoral database are useful starting points.

Demilade studies public policy at the University College London and works as an analyst for the African Elections Study Group. He can be reached on Twitter via @demiladeosoteku.

Data for the charts and the article were sourced from the Independent National Electoral Commission, The Cable, and Premium Times.

Add a comment