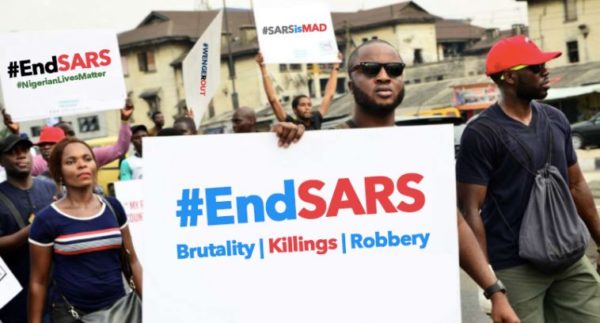

'They frame, arrest and extort us' -- Nigerians on Twitter renew calls for scrapping of SARS

As I made to angrily start the car, he howled, “Move an inch from there! If I no waste you now and dem bury you today, call me a bastard!”

I froze. His voice clattered like pebbles jangled over one another. That word singed my flesh like a hot whiplash. He had his gun cocked on the instant, the right hand finger caressing the holster and the left playing menacingly on the gun’s midriff. His eyes dilated like a piece of red-hot coal. It was as if I had received a jab from a cruel nurse’s syringe. Or a hot punch to my chin that left me momentarily immobilized.

Slowly, I hopped out of the car, my mien sober in salutary surrender.

“Officer, I am sorry,” I muttered in a very gruff but effeminate voice; and as if to underscore the huge shape of my contrite spirit, I repeated it again: “Officer, I am really very sorry.”

Advertisement

The Mobile Police officer had stopped me on the Lagos/Ibadan expressway. I was returning from a lecture at the International Institute of International Affairs (IIIA) in Lagos, and en-route Ibadan. Inside the vehicle which I drove were two top editors of a Nigerian national newspaper, my friends, with whom I had gone to attend the lecture. We had been stopped by the police who demanded our “particulars.” With glee, I volunteered all he requested for, until he demanded for an MCR. Diffident and with a self-effacing righteousness, as if I were a scientist who had just discovered the vaccine to COVID-19, I made him understand that only a few days earlier, the Inspector General of Police had announced that possession or not of an MCR should not be part of the bother of police on stop and search duty.

Apparently grated by my diffidence, the policeman ignored me, shuttling arrogantly off to attend to another “customer,” armed with my vehicle particulars. Cross at his impudence, I had angrily beckoned on my colleagues, who, exasperated, had come out of the car as the exchange between the policeman and I seemed to be reaching its crescendo. “Hop in the car and let us leave this man!” I bellowed, as if I held the lever. And that thundering threat of wasting my flesh was the riposte, a threat which immediately reset my brain to its default.

My contrition got me a lecture on the psychology of the Nigerian policeman from the Mobile Policeman. “Come rain, come shine, I dey here. Small boys like you just dey drive cars up and down. You think me sef no like better thing? If I waste you, I will run away…” he tutored.

Advertisement

The event above happened exactly 17 years ago but its purport has lived with me ever since. While police brutality on Nigerians isn’t a new phenomenon, it has festered embarrassingly. Right since its establishment in 1820 by the colonial government, the concept of a conquering police which came to subjugate the colonies, has fitted the Nigeria police perfectly. For Nigeria, policing began as a 30-member consular guard in the Lagos Colony in 1861. In 1879, the colonial government went ahead to form a 1,200-member armed paramilitary Hausa Constabulary for this purpose. In 1896, it also formed a similar one called the Lagos Police and in Calabar, the Niger Coast Constabulary in 1894, which it placed under the Royal Niger Company of Turbman Goldie. Goldie’s company also set up the Royal Niger Company Constabulary in 1888, headquartered in Lokoja. Even with an indigenous Inspector General, in the person of Louis Edet and up till now, the British concept of the policeman as a conquistador has not changed.

Transiting variously from the Royal Niger Company Constabulary to the Northern Nigeria Police in the 1900s and the Niger Coast Constabulary, becoming the Southern Nigeria Police at the advent of Northern and Southern Protectorates, Nigeria police was essentially known to operate at the local government levels called native authorities. It performed conventional duties of internal security giving prisons, immigration and customs support. At the creation of Police Mobile Force unit as a strike force to counter civil disturbances, the stage was set for the maturation of that colonial picture of the police as instrument of repression and oppression.

The Nigeria Police has gradually decayed up till this point where maggots wriggle out of its body. The height of its shameful repression of the people it was paid to protect and the ignominy emanating therefrom was the August 17, 2010 damning report on its atrocious policing by the Human Rights Watch (HRW). The report, illustrated with two fat-stomached but raggedly policemen with pristine guns barricading the road, had a danfo driver stopped by them saying, “O.C. nothing for the boys today, I beg because I no get change” and the police replying, “Bring am, we get change.”

HRW lamented the “extortion, embezzlement, and other corrupt practices by Nigeria’s police,” which it said “result in “the myriad human rights abuses committed by police officers in the process of extorting money.”

Advertisement

Today, Nigerians are on the streets to protest these abuses which range from arbitrary arrests, unlawful detention and criminalizing youthful manifestations. In the narrow world of Nigerian policemen, bushy, dreadlocked hair and I-Phone approximate crime. There have been cases of physical and sexual assaults, torture, extrajudicial killings traced to the police and covered by the HRW reports. It is very rare to identify a home in Nigeria which had not suffered the casualty of the Nigeria police’s bestial policing.

Either they are unaware or simply blinded their eyes to it, attentions of police authorities or the Nigerian government at large, seem to have selectively skipped the pestilential extortion of money on the road and in police stations, as well as the gross criminalities emanating from those places. Police extortion is such a lucrative, though criminal venture, so much that allegations claim that the blood money proceeds from it are funneled right to the purses of top echelon of the force.

In and out of police stations, policemen have become such notorious armed leeches who terrorize the people, squeezing out their blood and cash and detaining them at random. This is in contravention of Justice Akinola Aguda’s ruling in 1968, in the thick of the fratricidal civil war, in the case of Agbaje vs Western Government of Nigeria, where his comment, still relevant in Nigeria’s jurisprudence, was, “In a democracy like ours, even in spite of the national emergency in which we have been for the past three years, I hold the view that it is, to say the least, high-handed for the police to hold a citizen of this country in custody in various places for over ten days without showing him the authority under which he is being held or at least informing him verbally of such authority.”

As the #ENDSARS protest escalates, protesters should endeavour to read that HRW report to discover that this cancerous affliction not only didn’t start today, it seems the point to begin if we indeed want Nigeria sanitized. The HRW further says, “The police commonly round up random citizens in public places, including mass arrests at restaurants, markets, and bus stops. In some cases of blatant deception, plainclothed police officers simply masquerade as commuter minibus drivers, pick up unsuspecting passengers at bus stops, and take them at gunpoint to nearby police stations where they demand money in return for their release. The police often make little effort to veil their demand for bribes, brazenly doing so in open corridors … Those who fail to pay are often… unlawfully detained… sexually assaulted, tortured, or even killed in police custody.”

Advertisement

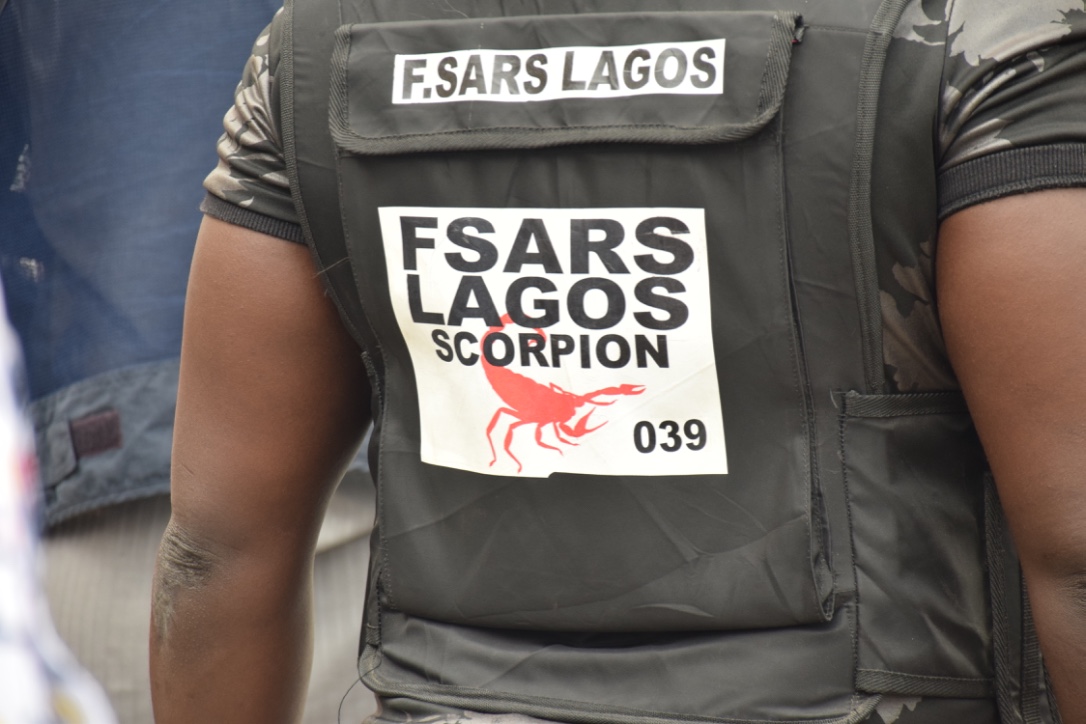

But if you ask me, demanding an expurgation of police Special Anti-robbery Squad, (SARS) is a small fraction of the task of purity in securing Nigeria. We must demand a total redraft of the Nigerian police architecture. The current equation is too iniquitous and prone to corruption and bloodletting. Though the newly promulgated Police Act 2020 is said to have redrawn the map of policing, I am not sure it has the power to melt the ice of the unmitigated avarice, bestiality and bloodlessness inherent in the heart of the Nigerian policeman.

To do this, we must start from the fundamental of the crisis, which is the personal dignity of the policeman. How many of us have taken time to visit a Nigerian police station or barracks? In the last few weeks, I have been interfacing with the police in Ibadan, Oyo State and I can tell you clearly that no one who makes a home of the environment which the police live can ever forgive the Nigerian state. Horrible, as an epithet, cannot capture the rot therein. Even animals should not be allowed to live in such environments. I presume that any child sired in such a place or even their parents will constantly hold Nigeria culpable and will ultimately have every cause to psychologically manifest animalistic traits.

Advertisement

This was why I was aghast at President Muhammadu Buhari’s reaction when, smoked out of his well-known lethargy by public angst at the animalism of the SARS and its aftermath of a volcanic eruption of anger of Nigerians towards the rank brutality of the police, in a Tweet, he merely off-handedly shoed responsibility of arresting the chaos to the IGP. Buhari had said: “The IG already has my firm instructions to conclusively address the concerns of Nigerians regarding these excesses, and ensure erring personnel are brought to justice. I appeal for patience and calm, even as Nigerians freely exercise their right to peacefully make their views known.”

When that Tweet came out, what came to my mind was that Emperor Nero image of Buhari which Nigerians got from a viral picture of him sitting in the Villa, with his babariga hanged by the wall, a toothpick hanging out from his teeth, cross-legged and dead to all worries of the world.

Advertisement

No, Mr. President, Mohammed Adamu cannot arrest the police rot because he is the Chief Maggot feeding fat on the decadence. It is your turf as President and Commander in Chief! It is this brand of escapism that Buhari is known by. The way it is panning out, the police may just be the route from where the much-talked about, anticipated explosion of the people’s anger at the rot in Nigeria may come from. Buhari should not play Nero. Nero, the decadent and unpopular Nero, you will recall, was not only playing music, literally fiddling with his guitar while that great fire ravaged the capital of his empire during the summer of 64 CE. In the words of Suetonius, his biographer, Nero “practiced every sort of obscenity,” which he said ranged from incest, cruelty to animals and homicide. He was reputed to have also outsourced Roman problems. Nigeria is burning over SARS’ and police brutality generally and the least President Buhari should do is to be seen trying to detect the roots of this inhumanity of the Nigeria police to Nigerian youths.

Advertisement

ICC: Wages of mediocrity and Gov Abiodun’s justification of nothingness

Two very symptomatic occurrences filtered into the system last week. One was the poor performance of President Muhammadu Buhari’s nominee for election to the International Criminal Court (ICC) jury, Justice Ishaq Usman Bello, Chief Judge of the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja and Ogun State governor, Dapo Abiodun’s decision to appoint winner of the just concluded Big Brother Naija and indigene of the state, Olamilekan Moshood Agbelesebioba, popularly known as Laycon, as Youth Ambassador of the state.

Juries of ICC, an organ of the United Nations General Assembly, are replenished every nine years for nationals of its 123-member nations. They are saddled with prosecution of war crimes, genocide, international crimes, crimes against humanity and aggression. The election is to be conducted at the 19th session of the Assembly.

Of the 20 nominees, however, Justice Bello and two others, upon grading by the committee saddled with their screening, were found to have fallen under the lowest category, next only to disqualification cadre and thus falling short of requirements stipulated in the Rome Statute for ICC judges’ election. Bello’s nomination was specifically spurned based on his lack of understanding of “the knowledge of the workings of the ICC.”

The ICC rejection of the nomination of Bello should be a wakeup call on Nigerians and particularly the Buhari government, on the futility of underscoring indices other than excellence in appointments and nominations. Nigeria shone in the past, both nationally and internationally, even when placed side by side the best of other countries because selfish considerations were absolutely relegated. First African to hold a PhD in law from the University of London, earned in 1949 and one who became Nigeria’s Attorney General in 1960, Teslim Elias, in October 1975, through his nomination by the Head of State, General Olusegun Obasanjo, was elected to the General Assembly and Security Council of the United Nations’ ICC. He subsequently rose to become its President, first African jurist to be so honoured and five years after, was appointed to the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague.

Ditto Justice Akinola Aguda. Nominated for appointment by the Yakubu Gowon government as Chief Justice of Botswana on February 3, 1972, Aguda became the first indigenous African to be so appointed and concurrently acted as Judge of the Court of Appeal of Southern African countries of Swaziland, Botswana and Lesotho.

However, over the years, the crevices of Nigeria’s divisions have jutted out embarrassingly. Runners of governments flee into mundane considerations when making national choices. It has worsened in the last five years where ethnicity is a major index in such choices. It is why Nigeria had to be thoroughly disparaged by the ICC in the choice of Justice Bello. The question to ask is, was Buhari the appointer, not aware that Bello was incompetent for that office? If so, why did he nominate him? Because he was Hausa? Were there no competent Nigerians at that point of nomination?

Another symptom of Nigeria’s tumble from the Olympian heights of hitherto-held values was Abiodun’s choice of the BBNaija star, Laycon. In an announcement made while he played host to Laycon in his office in Abeokuta, the governor handed him a three-bedroom bungalow and N5 million. His justification for this was that Laycon “will help inspire our teeming youths to channel their energies towards positive engagements and shun vices such as robbery, drug abuse, cultism, advanced fee fraud, cybercrimes and kidnapping amongst other negative tendencies.” He had said what was being celebrated was “much more than the entertainment that the House provided” but what Laycon represented, which the governor said was “rare combination of prodigious intellect, academic excellence, multi-faceted talents, character and resilience.”

Abiodun’s decision to splash such humongous public funds on the entertainer isn’t as execrable as his justification of the act. Since he became governor, it is not on record that he had effectively paid traditional pittance bursaries to students of the state spread across the country nor has the state been known to have celebrated teeming mental excellence that precocious indigenes of Ogun exhibit in every sphere of knowledge.

If the governor wanted to “inspire our teeming youths to channel their energies towards positive engagements,” I dare say that “excellence” in a house of voyeur which the BBNaija stands for should not be the index of such inspiration. Rather, what that celebration inspired is belief that personable and excitable engagements, as against mental engagements which hold hope for advancement of societies, were more desirable. It can even be said to have been an attempt to play to the gallery and appropriate cheap adulations. What those who cite the celebration of footballers and award of humongous sums of money to them as justification for the Abiodun mis-vote of money to personable engagements forget is that, no nation becomes great on account of “It is a goal!” nor are great nations made out of such Abiodun excitable ventures.

Goodnight, Joseph Chijioke Oyibo

Two days ago, 57 year-old Joseph Chijioke Oyibo, who died on September 21, 2020, was interred at his Amutu village in Ezi-Nze, Udi local government of Enugu State. Oyibo, a civil servant of decades, was said to have died of cardiac arrest. Oyibo personified whatever definition anyone may think up of a good man. He was humble, honest to a fault and loyal. In four years of my stay in Enugu and about five years day-to-day relationship with him, Oyibo mirrored the trinity of the Igbo character.

Borrowing from the man who espoused this trinity, Dr. Chimaroke Nnamani, Ndigbo, from their Nri cradle, which they term the Holy City, espouse and venerate the Cot of Reason called akpa uche, which then manifests in the physical gesture of aka Ikenga. Its end product is accomplishment, called ntozu. When this accomplishment is celebrated, according to Nnamani, it is Odenigbo – the universal applause for fame. This trinity of Igbo character is expected to be manifested both home and abroad. Oyibo manifested this trinity while alive and at Amutu, in Ezi-Nze, Udi local government on Friday while his remains were being interred, he received affirmations that he was a moral accomplishment, receiving applauses for his humanity while alive.

Whenever anyone asks me what were my takeaways from those days of sojourn in Enugu, Oyibo and a few others were my measurement. It is why I always conclude that good and bad men inhabit all lands, whether Igbo, Hausa, Fulani or Yoruba.

We will all miss this good man, even as we wish him a peaceful journey to the territory of the immortals.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment