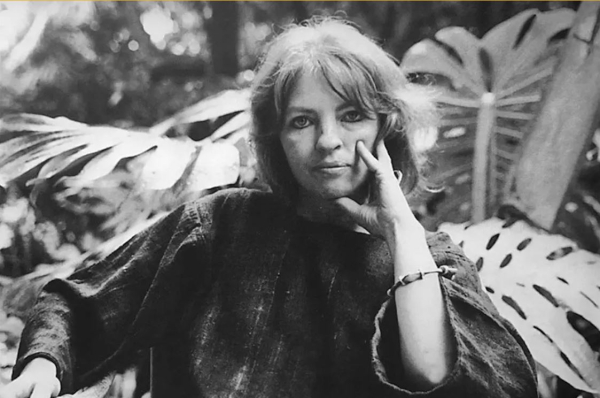

There is a popular saying among the Yoruba of southwest Nigeria that: It is on the day one dies that one becomes an idol. This truly illustrates the passage of art pioneer, Georgina Beier (1938-2021), in Sydney, Australia, on July 11, 2021.

To say Georgia is now an ancestor is to give credence to this belief. Born in London as Georgina Betts, her life took a dramatic turn after she dropped out of the Kingston Art School and migrated to Zaria, a cosmopolitan city in northern Nigeria, in 1959. Her keen interest in the art of the locals brought her to the south of the country where she met German writer, author and editor, Ulli Beier, whom she married and moved with to Osogbo in 1963.

It was at Osogbo that Georgina’s talents developed and were able to inspire a generation of artists. Her experimental workshops organised and conducted at the Mbari Mbayo Club, Osogbo, beginning from 1963 to 1966, established what later became known as the Osogbo Art School. Here, international artists such as Rufus Ogundele, Twins Seven-Seven, Bisi Fabunmi, Muraina Oyelami, Jimoh Buraimoh and a host of others were trained and mentored, although Georgina often rejected such attributes. She believed that the retinue of artists familiar to her were colleagues and friends who evolved together and influenced one another such that what each one of them became could be attributed to artistic collaboration. Many of the beautiful costumes, sets and colourful backdrops for the Duro Ladipo Theatre were personally made by her.

In 1966, shortly before the Nigeria Civil War, she and her husband departed Nigeria, arriving first in London and then later in Papua New Guinea where she tried to replicate Osogbo in her new domain. Given the different culture and environment, this proved a bit difficult yet she was able to muddle her way out. At the University of Papua New Guinea where she and her husband had been employed, she was able to commence a robust arts movement as she did back in Osogbo. At her new abode, she was not only able to identify rare talents but also developed them. Two of the most prominent of these new talents include Papuan New Guinea’s best-known contemporary painter and sculptor, Mathias Kauage (1944-2003) and artist, Timothy Akis (1944-1984). It is impossible to describe or explain her impacts in Papua New Guinea because she was involved in very diverse art projects.

Advertisement

Her body of work included graphics, lithographs, theatre design, murals, mosaic, textiles, furniture design, and sculpture which brought her global fame and recognition. These prolific outputs also featured in several private art collections but, most importantly, were several illustration publications, for instance, When the Moon was Big and other Legends from New Guinea, was produced by her writer husband, Ulli Beier. She was said to have established Papua New Guinea’s silk screen textile printing industry, formed the nucleus of the National Art School in the country and like her husband at Lantoro Psychiatric Hospital in Abeokuta, southwest Nigeria in the 1950s, she introduced painting to psychiatric patients at the country’s Laloki Hospital.

She returned to Nigeria with her husband in 1972 and became a research fellow at the Institute of African Studies (Institute of Cultural Studies from 1983), University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University). Typical of Georgina, she quickly set to work by assisting with the Design Workshop where graphic prints, ceramics, textiles and posters were produced. Her imprints can still be felt in and around the campus of the University. The Beiers had a brief stay in Nigeria and later moved to Germany where they founded the Iwalewahaus, University of Bayreuth, in 1981. Iwalewahaus, derived from the Yoruba word for Iwalewa (character is beauty), served as a melting pot of global cultures as well as a hub for artists and their works. Many artists the Beiers had met and collaborated with in the 1960s and 1970s were invited either as artists or scholar-in-residence to Iwalewahaus to experience a whole new world and also to promote their arts. Georgina was said to have designed the profile of Iwalewhaus along with Ulli and also gave this artistic site its beautiful name. In terms of its content aspect and aesthetic character, Georgina provided the basic wherewithal, a vision that continues to determine the lifeblood of Iwalewahaus up till this moment.

Despite her ever-busy artistic itinerary, Georgina never stopped keeping in touch with her artist friends around the world. Between 1991 and 1994, when Ulli Beier returned as Director of Iwalewahaus, Georgina visited Nigeria at least twice a year to connect with old friends and hold exhibitions at the Nike Art Centre in Osogbo. Through her initiative, several young men and women, in particular, were trained in different art skills for which they later became financially independent and artistically relevant across their local communities. Around the same period, precisely in 1992, she and Ulli were conferred with chieftaincy titles by the king of Osogbo, Oba Iyiola Oyewale Matanmi II. She, like her husband, would gladly accept a title among the local Yoruba people than a prestigious honorary degree or recognition elsewhere. Such was the love Georgina had for Nigeria and the Yoruba that she could be easily regarded as a black soul in white skin.

Advertisement

Throughout her life, she held more than thirty solo exhibitions and participated in over twenty-five group exhibitions around the world. A writer refers to her as an extraordinary artist and a contemporary witness which is no ordinary compliment. Georgina was, indeed, unique in the sense that she was from a different culture and yet never imposed it on the local people she met across the world. Rather she made them aware of their rich culture and heritage and exposed their creativity to the world and the artists within her circle. One can liken Georgina to a missionary – she did not come to Africa with the Bible in one hand and with the sword in the other but with brushes and a bag of knowledge. This is, no doubt, the legacy she leaves in our lifetime. Her works will not be forgotten because they endure in the hundreds of lives she impacted.

Raheem Oluwafunminiyi writes from the Centre for Black Culture and International Understanding, Osogbo, and can be reached via [email protected]

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment