BY PELU AWOFESO

“This country is bad!” cries Tony, one of the main characters in Cornel-Best Onyekaba’s punchy play, Fela: Son of Kuti.

A moment later, he laments: “Our Republic is over. Kalakuta has been razed to the ground…Kalakuta is gone forever.”

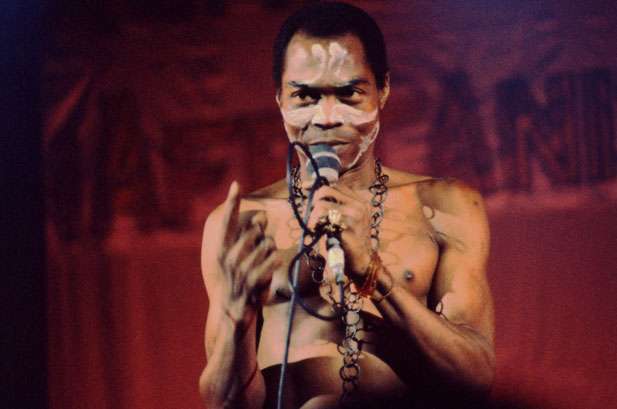

Time check: what’s unfolding before our eyes inside the National theatre is a playwright’s re-imagining of what might have transpired among Fela’s band members on the morning of 18 February 1977, a day after the Nigerian military attacked and sacked the Kalakuta Republic, where Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, then 39, lived with dozens of dependents and his aged mother, the political activist Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti.

As soldiers marched on the premises, Tony and some of Fela’s band boys and backup singers fled to the nearest safe shelter they could find, from where they played back the mind-bending brutality of the previous day; hungry and bruised, they agonized over their misfortune, collective loss and the uncertain future that stared them in the face. To make matters worse, their breadwinner’s whereabouts was unknown and the one place they could confidently call ‘home’ now existed only in their memory.

Advertisement

Through the characters’ dialogue, occasionally punctuated by pidgin (the Republic’s language of choice), the audience were transported four decades back in time and space to witness one of Fela’s many run-ins with the law, a tense episode that would reshape the story and evolution of the Afrobeat movement.

From Tonia, the teenager Fela found and removed from the vicious Ojuelegba area, we learn that the soldiers’ assault was merciless; they shot tear gas in every direction and pumped the building with bullets. Apparently acting on instructions from the authorities, the ‘Zombies’ (as Fela would later refer to them in a song) were on a mission to kill, steal and destroy – literally.

“Before anybody know wetin dey happen, two officers push mama (Fela’s mother) out from window,” reveals Iyabo, another backup singer.

Advertisement

As they debated why Kalakuta was meted with such cruelty, another crisis broke out, and this time it had nothing to do with guns and batons: the band began to relive the good times of the pre-Afrobeat years, when Fela played highlife-cum-Jazz music for its entertainment value only, not as a weapon against the junta.

“Don’t pretend you don’t know how Abami Eda brought this whole tragedy upon us,” Tony throws the first stone.

“When we were koola Lobitos, we just dey play our Jazz and highlife dey go; we dey make big money like our oga’s master, Victor Olaiya. When we sign, people go dey spray us money – everybody like us that time well well.”

Of course, some of the other band members thought he was talking rubbish and they challenged him accordingly.

Advertisement

“Just one day and you have denied Abami Eda more than three times,” Niyi lashes out, wracked by the pangs of a broken left leg.

“If you have always felt this way about his ideologies, why did you remain in the band all these years? You should have declared your position and gone your separate way. Instead, you stayed back and constituted yourself into a rebel within a rebellion.”

While the in-fighting lasts, it is soon revealed that there have been moles in Kalakuta all along, who leaked details of Fela’s every move to a government that was hell-bent on shutting Fela up for good.

Advertisement

Fela: The Son of Kuti is a gem of a play – one that needs to tour Nigeria and the world; it is a play that should be seen by Every Nigerian alive, young and old. The playwright provides uncommon insight into the side of Fela less well-known to the public, one far removed from the ‘bad boy’ persona perpetually projected in the media of his time.

It gives a glimpse into the circumstances that inspired some of his hit songs; it shows the “Black President” as a good-humored, humane character who was ultra-sensitive to the predicament of the masses. Perhaps, Fela was the only musician of his generation who welcomed societal rejects and castaways into his commune and invested his resources to make them better than he met them.

Advertisement

“It is only a perpetually damned fool that will spend a night with Abami Eda without undergoing a mental revolution,” another back-up singer, Iyabo, says as the argument for and against their leader raged.

“Yes, I dropped out from school but Fela has filled up the missing gaps and today I can boldly challenge any professor of history on any aspect of ancient and contemporary African history.”

Advertisement

The Abami Eda was that good.

Advertisement