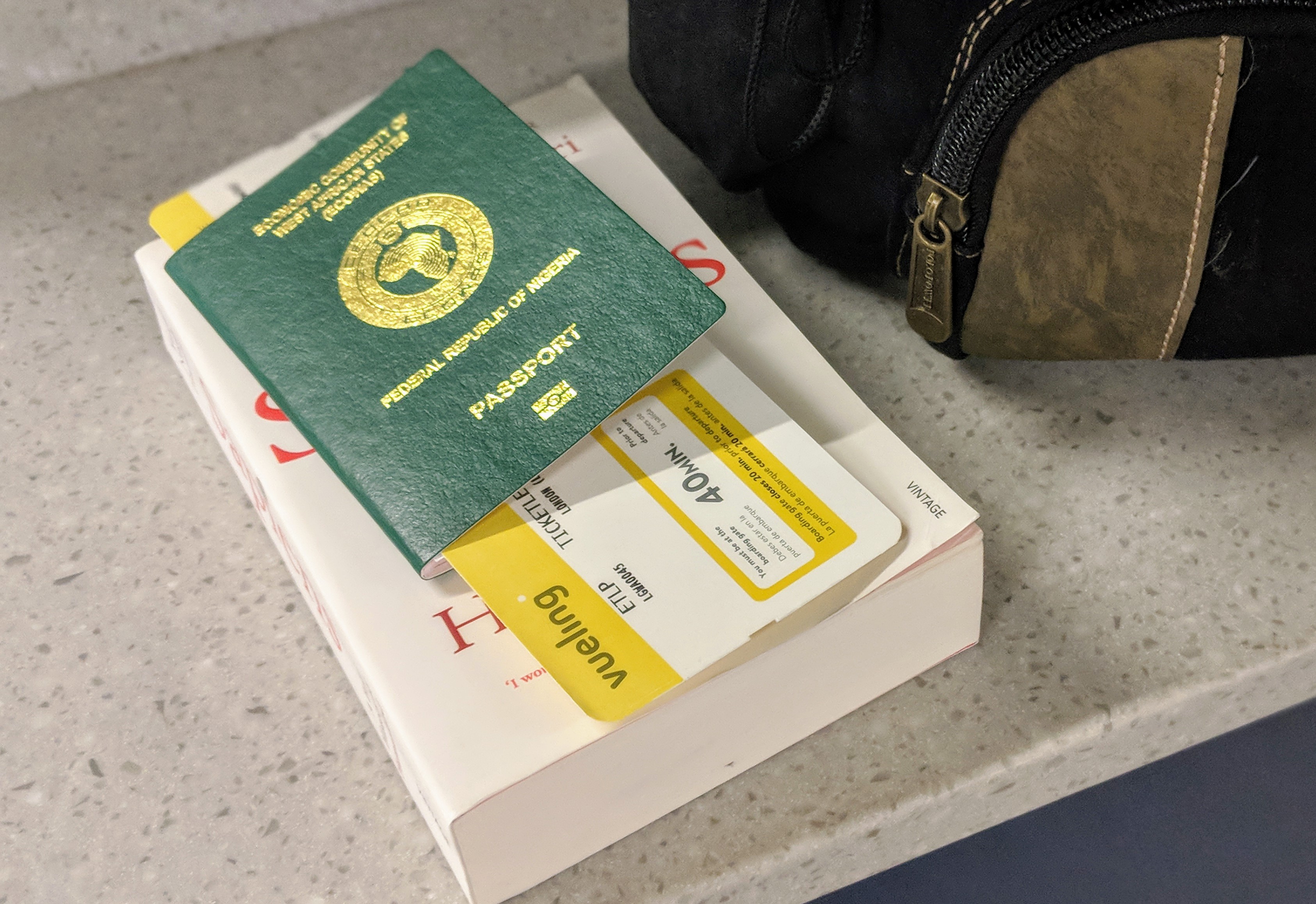

Africa is a young continent, in fact, Africa has the youngest population in the world – people below the age of thirty-five account for over 70% of its population. This army of young people can either be advantageous or otherwise to the long–term prospects of the motherland. One topic that has gained notoriety over the past decade is that of brain drain; the emigration of especially young and genius minds from Africa to the global west.

In my home country of Nigeria, about 700 medical doctors educated in Nigeria did move to the United Kingdom between December 2021 and May 2022 – raising the number of Nigerian doctors practising in the United Kingdom to around 10,000 personnel – the third highest number for foreign doctors, only behind Pakistan and India.

However, such numbers, just like elections – have consequences. For these individuals, it would be disingenuous to anyone to legislate “patriotism” to them because they chose to leave to where the proverbial grass appears greener – their decision may really be the result of multiple causalities. The World Health Organization recommends a minimum doctor-patient ratio of 1: 600 and a nurse-patient ration of 83: 10,000. Nigeria’s numbers are abysmally below those mean with one estimate putting our doctor-patient and nurse-patient ratios at 1:3,000 and 15:10,000 respectively. It therefore comes as no surprise that Nigeria with a population of over 200 million shows up as one of the three top countries in the world where the infant mortality rate is highest. When next you hear that Nigerians are the most educated immigrant group in the United States of America, the question is: what is the net benefit or loss for Nigeria?

During our meeting with former President Barack Obama at YALI (Young African Leaders Initiative) in 2015, he wanted to take a question from a young man in a suit, so there I was in my bespoke suit with my hands raised. Gratefully he indulged me, this was my question:

Advertisement

“I want to say we appreciate all the great work that the United States is doing with Nigeria and many other African countries, especially as it concerns infrastructure development policies and all of those. But I’m of the opinion that if we do not make investment in education more than any other sector of the economy, then we are not building a sustainable partnership. And I’m saying that with respect to the fact that we are all of the intellectual dream that Africa is experiencing. Due to the fact the grass seemed green on this side and then the United States attracts so many intellectuals, we should have stayed to develop and grow these programs.

For example, recently, when you were in Kenya, you launched a project around power and energy. I’m of the opinion that if that program is going to be successful and sustainable, then all of those programs should include the partnership of universities because through that, we can build the capacity of universities, and then those countries can go around in other African countries replicating that. So in that case, we can control the dream that is moving from Africa to the West, or to any other part of the country.

So I want to ask, what is the United States doing to control this intellectual dream to the Western world? And what are you doing to increase, more than others, the investment in education so that our partnership and development can be truly sustainable? Thank you.”

Advertisement

As the first-ever African-American President in the White House, who could relate to both ‘worlds’ he gave a very instructive response: “The question isn’t what the United States doing to reverse the brain-drain, the question is what is your country doing to reverse the brain-drain?“ He went further to state, amongst other cogent reasons why people generally gravitate towards countries that democratise opportunities as opposed to those where pedestrian considerations such as graft, gender, impunity and ethnicity largely determine access.

In his words: “The issue is not just that we’re a wealthier country. I think it’s fair to say and you know better than I do but part of it has to do with a young person’s assessment of can I succeed in applying my talents if, for example, the economy is still built on corruption so that I have to pay a bribe or be well-connected in order to start my business. Or are there still ethnic rivalries in the country, which means that if I’m from the wrong tribe, I’m less likely to advance? Or is there still so much sexism in the country that if I’m a woman, then I’m expected just to be at home and be quiet when I’m a trained doctor? Or is there a lack of rule of law or basic human rights and freedoms that make me feel as if I am restricted in what I can do?

I make this point to say that some of the brain drain is economic. But some of it has to do with people’s assessments of if I stay in my country, am I going to have the ability to succeed? And that’s why, when I talk to leaders in Africa, or anywhere around the world, I say, look, if you put together the basics of rule of law and due process and democracy, and you’re able to keep peace so that there’s not conflict and constant danger, and the government is not corrupt, then even a poor country, you’re going to attract a lot of people who are going to want to live there because they’ll feel like they’re part of building something and are contributing something.

That doesn’t mean that there aren’t going to be some people who would still rather live in London or New York because they think they can make more money. But I think that, as much as anything we do, is going to reverse the brain drain. And that’s why what you do is going to be so important, because if you set a good example of going back home and rebuilding your country, and if you, as young leaders, are creating an environment in which young people can succeed and you’re setting a new set of expectations about how exciting it is to be part of something new that can help turn the tide.”

Advertisement

His response captured a lot of my own thoughts; it’s really up to us as Africans to ensure that we create not just an enabling environment but a competitive environment for our young people to thrive. It’s encoded in humans to seek for better conditions of living; it’s a natural response of adaptability. So, the Japa Syndrome (Nigerian colloquial term to the obsession by especially young people to emigrate to developed countries) is more of an effect, not a cause. Here are some of the low-hanging fruits that can be tapped on the journey to retaining more of our best brains on the continent.

• Functional learning: educational tourism is one of the drivers of emigration amongst young people. When a government fails to provide the very basic infrastructure for the academic community to thrive, it’s inevitable that in the 21st century where the world has become a global village, the need to remain competitive amongst contemporaries who are not necessarily operating within the confines of the same geopolitical space, causes them to gravitate towards climes where cutting-edge innovations, global best practices and cosmopolitan curriculums are taught. African leaders must see allocation for education as an investment not an expense; otherwise, we are just training our eggheads at low costs – only to lose them to countries that prioritize education.

• Medicare: it doesn’t help that medical tourism is championed by African leaders, who, instead of establishing a functional, accessible and relatively affordable healthcare system, see the ability to get medical attention abroad as a status symbol. Effective primary healthcare should be non-negotiable, when the average citizen is exposed to health crisis without access to health maintenance organizations and have to routinely pay out-of-pocket for their basic health needs, it’s only a matter of time before those who can afford it, move to climes with more comprehensive health systems.

• Rule of law: when a country operates an Orwellian philosophy where some animals are more equal than others, it effectively puts large swaths of the population and other social classes at risk because they are not part of oligarchy or ruling class. The greater the democratization of socio-economic opportunities, inclusion of minority groups, effective jurisprudence and independence of institutions – the more invested young people will become in domesticating their skills and expertise.

Africa and Africans must take greater responsibility for both her future and fortunes instead of outsourcing them to others. No one is coming to save us, there are no messiahs out there – we are the ones we have been waiting for. As we mark the 2022 International Youth Day, we truly need to leverage the potential of all generations – particularly the younger demography.

Olusola Owonikoko is an international development practitioner and social entrepreneur. He tweets @Solaowonikoko.

Advertisement

Add a comment