Since 2009, Nigerian soldiers have been going into battle with Boko Haram — with far inferior arms and ammunition — knowing this is the only proof of their love for fatherland. But once they sustain injuries on the battlefield, they soon discover that this love is unreciprocated. ‘Forgotten Soldiers’ is a five-part series exploring the agony of soldiers shattered by Boko Haram’s bullets and mines, and what their pains mean for their loved ones.

“I married him because I love him; there was absolutely no chance of me going for another man,” she says, flashing a rare grin before taking a flash to re-admire the man she married at a muted ceremony in Kaduna a little less than a year ago.

But those were not the words of an excited young bride tossed into delirium by a momentous opportunity to tell an enchanting love story. Instead, they were the words of a young lady already matured by emotional adversity; they were the reflections of someone who had experienced both the illumination and darkness of love — someone who, at just 24, had become an epitome of the for-better-for-worse language of love.

Joy Johnson may have had only one man all her life, but the man she married in 2015 wasn’t the man she met and began dating in 2009. Seven years ago, she met a young, handsome civilian who rode a motorcycle for a living in daytime but trekked long distances with her at night for their daily routine of sharing sweet nothings. But one year ago, she was left with an amputee, a man who could no longer mount a motorcycle or walk a minute without aid, a man with whom sharing the rest of her life represented more of a burden than paradise. Yet she chose to marry him.

Advertisement

Johnson had just finished serving breakfast to her husband and his army of equally-injured friends when she sat down at the 44 Nigerian Army Reference Hospital, Kaduna, to narrate how she embarked on a journey that continues to test the resilience of her love. As she spoke, it was impossible not to admire the see-through beauty percolating from her face to her heart. What she had lost in limited education, she made up for with her strength of character.

Sweet lover in the oily village of Ogoni

“I met him in 2009,” she recalls, slipping into the melancholy that defined her entire afternoon.

“He hadn’t joined the army then; he was a motorcycle rider. He joined the army in 2011, then this tragedy happened to him in 2012.”

Advertisement

By “this tragedy”, Joy was referring to a raid by Boko Haram on Giwa Barracks, Gombe state, during which her husband suffered multiple gunshot injuries, the most severe of which led to the amputation of his leg in 2014. By that time, though, her husband had already done enough to convince her she owed him nothing but unfettered loyalty in his moment of tribulation.

“He won my heart with his character; I liked his way of doing things,” she says, casting a gaze at him as though wishing for the emptying of their past into the present.

“He was very calm and measured in his ways. If I asked him for anything, he never got angry; he never rebelled against the things I liked. He was always soft with me and he treated me really well.”

Joy says that back then, when Nwibani had his legs, he was a “very sweet” lover who broke bounds to please her.

Advertisement

“He was very caring. He would wash my clothes and even cook for me,” she adds, her face lighting up with positive emotion.

“He still does it, but surely not as often as before because even me, I won’t be able to bear it watching him wash my clothes in this condition.

“Back then, there were times when I was in the living room and he would be in the kitchen cooking for me — that time when his legs were intact. But now, all he can do in that regard is that if I’m in the kitchen, he’ll come and stay with me, playing with me and supporting me.”

The lovebirds were both in their Kana Gulle village in Ogoni, Rivers state, at the time. But when Nwibani joined the army in 2011, he was posted to Gombe state. This rendered their romance long-distance, but the fire continued burning as fiercely as it did back when they saw every day.

Advertisement

In October 2012 after he was shot in the leg, Joy literally became a nurse overnight, devoting several hours of her every day to tending to her husband’s wounds. The setback of the time didn’t seem like a dead-end; the army had promised him a prosthesis. In fact, Kenneth Minimah, a retired lieutenant-general and former chief of army staff, had visited him in hospital and a photo of the duo graced the 2015 calendar of the Nigerian army, as proof of the army’s preparedness to “go to any length” in looking after injured soldiers.

“Immediately the tragedy happened in 2012, they told him they would give him an artificial leg,” she recalls. “Last year, the army took him to Lagos for an artificial leg, but the one he was given is actually fake. It’s not something he can use.”

Advertisement

Wedding after amputation

By 2014 when the leg was eventually amputated — after some careless medical mishandling culminating in the sight of maggots in the leg — they had been dating for five years and tying the knots was overdue. In 2015, she married him, despite protestations from a few “well-wishers” who thought she deserved more than a “one-legged solder”.

“Some people told me to leave him, saying I should not marry an amputee and I should find another man, but no way!

Advertisement

“My mind didn’t work that way. There was absolutely no chance of me going for another man. My mind didn’t tell me to leave him, and I cannot do anything my mind doesn’t tell me to.”

As the endless wait for original prosthesis continues, Joy continues to serve her man as both wife and caregiver, helping him run the home, run errands, fetch water — helping him do everything a man with two legs would have done for himself, or what a prosthesis would have helped him do.

Advertisement

“I don’t have a job and I can’t have one yet because taking care of him is itself a fulltime job,” she says.

“Now, I help him fetch water when he needs to bathe or use the toilet. I prepare all his meals and wash his clothes. I do everything that he can’t do or that he can only do at great physical cost.”

Asked what she would be doing had her husband been given a prosthesis, she says: “You know, if I got some help, with just N500,000, I could set up a petty provisions business with which I can support him more.

“But, of course, even the business would be meaningless without prosthesis for my husband.”

Nwibani himself does not regret the choice of woman he made several years back. Without her, he says, it would far harder to cope with the loss of his leg and the army’s failure to redeem its pledge of a prosthesis.

“Now, there are so many things I cannot do by myself and when I tell her to, she does them without complaining,” he says with a smile in appreciation of his woman, which quickly thins out into a frown betraying his helplessness.

“The truth is I can no longer meet up with taking care of myself; she is the one who runs errands for me — up to the simplest of them such as buying odds and ends for me. Personally, I am not happy with my condition; I’m not happy that I can no longer fend for myself.”

No one to turn to

Take Joy out of Nwibani’s life, and there isn’t much to be joyful about. His father died back in 2010, leaving his aged mother and two sons. He has never had a sister. His only brother was shot dead in January 2016 during the bloodily-contested Rivers state legislative rerun. All these mean he is grateful for life.

“When I look at all I have experienced, I probably should not be alive by now; I should have died,” he says. “I know the pains I endured on the day I was shot. It was like dying every day — dying every morning and night. But I told God to promise that I would not die, and God preserved me.”

But they also mean he has “no one else to turn to”, which explains why neglect by the army hurts him that much.

“I am happy with God — but not with the army,” he says bluntly.

“Look at me? Should I be in this condition for four years? Would it happen if I were their son or if my wife were their daughter? We don’t need their money; it is just to pay us our salary and allowance, and give us good treatment. If all these happened, nobody will grumble.

“But with the state of things, do you think anyone who knows me will be willing to join the army? When I travelled to my village, people were discussing me in hushed tones, wondering why a soldier should be in my sorry state.”

Nwibani reiterates that he asks for only one thing from the army: the chance to get as close as possible to his pre-attack physical state.

“All I need from the army is my leg — original artificial legs,” he says.

“I cannot continue using these crutches because they hurt me and leave marks on my ribs. If the army says move and you don’t, you are dismissed. But they told you to move and you did… you are now injured but the same army is not ready to take care of you. That is not fair.”

LOVE SEALED AT THE BARRACKS

Nnenna Aguba (not real name) was eight-and-a half-months pregnant and in another two months, she would be calling her soldier-husband fighting Boko Haram in Borno state to inform him of the birth of their latest baby. Instead, it was her husband who called; he had been shot in Gunun Kurmi by insurgents and was recuperating at the 7 Division Hospital, Maiduguri.

Her husband, Benjamin, tall, sturdy and larger-than-life, is that kind of soldier born to face an insurgent group as recalcitrant as Boko Haram. First injured on September 1, 2014 when his forehead was gashed by fragments of a Rocket-Propelled Grenade (RPG), Benjamin spent six weeks at the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital before heading straight back to the battlefront!

“I was first injured in 2014 when Boko Haram dislodged my entire unit from Bama. “As we were fighting on, they fired RPG, let me say 50 to 60metres from me,” he recalls vividly.

“It was just a passing fragment, so you can imagine what would have happened if the thing had met me directly. It would have affected my brain or I would have died. Fragment is very dangerous, RPG fragment, especially the heat.”

Soldiers withdrew when they were overpowered by that onslaught from insurgents, but Benjamin returned from the sick bed to help the army recapture the town “after six to seven months of planning”.

In December 2015, he was nailed again, this time in a deadlier attack. Forty soldiers had conquered a village and were preparing to advance to Alafa, another village, when hundreds of insurgents attacked them.

“When they attacked us, we pinned down and we were launching. But because they knew the location more than we did, they took another route and suddenly started attacking us from our rear.

“I was firing mortar, the 60mm; that is why they were looking for me. I fired two bombs already, and I got many of them. When they hit me, I tried to run but no way, so I fell down because the thing broke my bone. The bullet charged through my bone.”

Woman of gun (and God)

When news of his injury got to Nnenna, a soldier herself, she offered praises to God rather than panic.

“When he called to say Boko Haram shot him in the leg, I said ‘Thank God that you are alive,’” she says, slapping her two palms against each other. “I am a woman of God, so I gave God the glory that it was not his life that was taken.”

In a matter of months, she had two ‘babies’ to care for — one, the one she carried in her womb for nine months; the other, the one who was shot in Borno and was back home to continue his recuperation after surgery at the hospital. As she cleaned and bathed and breastfed her toddler, she also fed her husband and cleansed his wound — all these in addition to rendering financial support for purchase of drugs.

“We spend a lot for the treatment. I have had to assist,” she admits.

“They take care of them at the hospital but we have also bought some minor drugs with our money.

“I support him because we are together in that we run a joint account. Some drugs we buy, while some are given to him there. But when he is at home and the drugs finish, we buy with our money.”

What God has joined together…

These sacrifices must have been easy to bear for her because theirs is one of the most intriguing love stories that could possibly emanate from the army. The two soldiers met in Lagos and within two months decided to spend the rest of their lives together.

Did it bother her that getting married to a soldier like herself was too big a risk to take, particularly for her children?

“It’s not risky,” she says with cocksureness. “It’s God that joined us together and what God has joined together, no man can put asunder.”

True. Both lovers should actually never have come together. That they eventually did must mean that nothing else can possibly put them asunder.

When Nnenna met Benjamin in 2010, she hadn’t even weaned the baby she had outside wedlock. Her ex, again a soldier, had thrown her out when he learned of the pregnancy.

“He sent me away, shouting at me that he didn’t love me and I should go and throw the child away,” she says slowly, soberly.

“My mother told me to report him at the office so that he could be responsible for the baby’s upkeep, but I told her I wouldn’t do that because I had committed him into God’s hands. The truth is that I had already forgiven him.”

Too good to be true

Perhaps Benjamin’s entry into her life was reward for her graciousness because within two months he not only desired to marry her, he vowed to take care of the baby.

“I told him everything that happened, the way my son’s father behaved to me,” she adds, her voice gradually becoming boisterous.

“He felt for me knowing I am a nice person. He wondered why someone would behave to me in that manner. He told me not to worry, that he would take care of the baby.

“He told me to allow my ex walk away, and not ask him for a dime over the upkeep of the baby. He said he would take good care of the baby, and even pay the child’s school fees. Even you, if you were me, wouldn’t you be happy?”

Those two months were the most shocking of her life; it all happened too fast for Nnenna to accept that it wasn’t a dream that would come crashing in no time:

“I didn’t expect that with a child outside wedlock, he would want to marry me so fast,” she concedes. “I was surprised. I was still in pains at that time because of what the other guy did to me.”

It is now six long years since the unfurling of that “dream” but it doesn’t appear destined to end anytime soon.

“I am happy; he has been so nice to me,” she enthuses about the man for whom she has now borne two children. “We are doing fine. Everything is moving smoothly before God and man. I thank God that today, everything is okay.”

Which explains why she harbours no animosity against her ex: “I have already forgiven him from the depth of my heart; I have.

“If he comes later that he needs his child, fine. If he doesn’t, fine. I give God the glory.”

Her husband now spends more time at home recuperating from his gunshot wound, only travelling to Kaduna occasionally to honour appointments with the doctor. The entire burden of his post-hospital care now rests on Nnenna, and it is a role she is more than happy to fulfill.

“I massage the leg with hot water. Sometimes he can’t stand up, even to pee; I help him up.

“I support him to the bathroom for his baths, I fetch water for him; I do everything for him. Sometimes it affects my work but I take time off so I can assist my husband, since he doesn’t have a leg.”

She intends to “continue doing everything” for a man who showed her the true meaning of love at a time when life meant little to her. And for this, she says she will not tire.

“I just love him,” she says, laughing sheepishly, childishly, unashamedly. “He is the one I love. I love him. He is so nice; he doesn’t have problem. He doesn’t hurt me; he pets me all the time.”

This love is the reason Benjamin can see out his recovery period with grace and look forward to the future with optimism.

“I will be patient till my leg heals,” he says, “because I’m returning to Borno once I’m fit; we have to finish off these foolish Boko Haram guys.”

THE DARK, HIDDEN WORLD OF SLAIN SOLDIERS’ WIVES

It is not in all cases that, like Nnenna, a soldier’s wife has the good luck of enjoying years of her husband’s love. The Nigerian army is undoubtedly killing insurgents in their thousands, but it is also grossly underestimating its own casualties.

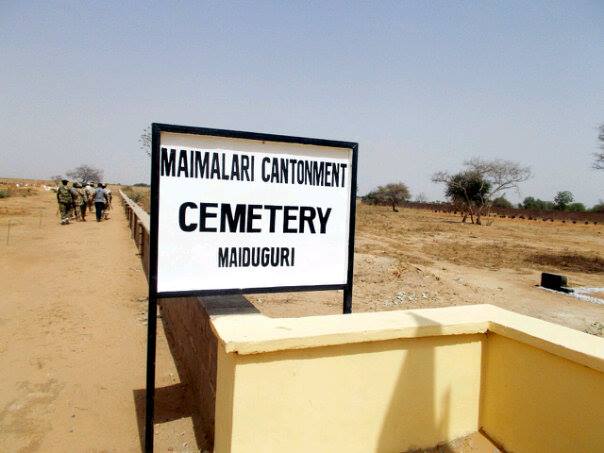

For example, privately-seen death records of the army show that 894 soldiers had been buried in 2016 alone as of mid-May — excluding soldiers who were declared Missing In Action (MIA) and their likely death undocumented. Rarely do families of fallen soldiers get timely information on the fate of their loved ones, and the wives are the biggest sufferers.

“I swear to God whom I serve, some soldiers were killed here more than three years ago, and as we speak, nobody in their family has been notified by the army,” says a soldier who was posted from Lagos to Maiduguri.

“There are soldiers who have died and their wives keep calling me for information on their whereabouts, but since I am not the army, I am not the authority, it’s not my duty to tell them that their husbands have died.

“I just tell them: ‘Oh… you’ve not heard from your husband? Maybe he is one of the soldiers posted to a location where telecom network is unavailable.’”

By his explanation, wives of slain soldiers who are young and beautiful, and are not connected to top army officers, are at risk of sexual harassment while trying to claim their benefits.

“If you die and your wife is young with pointed breasts, they must sleep with her before paying her,” he claims, buttressing it with the encounter of a late soldier’s wife whom “one officer” tried to sleep with.

“In the process of applying for her husband’s claims, the officer was trying to hug her,” he says.

“That’s when the woman told him to keep the money. She had to open the door and leave in annoyance. She never returned there!”

Architects of their own misfortune

Sani Usman, spokesman of the army, has “stayed in this system for quite a long time” to know that soldiers usually make a mess of filling documents.

An example is that of “somebody” who is happily married with a wife and a kid, but names his “father or younger brother” as his next of kin.

“Now, in the event of death, such people, especially if you marry from far away, will come with all sorts of excuses; hardly does the real beneficiary get anything,” he says.

“I am a living witness… someone headed to war and he died, and they come for the collection of children’s sponsorship. One of the wives was saying that she was seeing the other child for the first time.”

He maintains that “it is not true that you process over and over again and still don’t get it”.

He explains, too, that “there are certain entitlements that are the responsibility of the Nigerian army, while there are those that are the responsibility of the directorate of military pension board, such as the group life assurance, death benefits and the rest”.

“If the documents are not correct it will not be processed when due,” he says, but then tells families of soldiers still awaiting their claims: “They should exercise patience and have faith in the system.”

However, he doesn’t say how long this wait would last.

‘There will be judgement!’

Not that the documents required to be tendered for claiming these benefits are easy to procure, anyway. One of them is the death certificate, but how can it be produced for a slain soldier whose body the army didn’t retrieve from the battlefield?

“Your husband was killed in Sambisa and his body left to rot there or acid poured on him, how do you obtain the death certificate?” the Lagos-to-Maidguri soldier asks, stone-faced.

He cites the example of Monguno, where, last year, soldiers went to recover corpses of slain colleagues, only to discover that some had already dried up “with their rifles in position”.

“How do you claim entitlement for those kinds of death?” he wonders. “My own belief is that on the day of judgement, everyone will give account for his works. Many have gone but dry bones will rise again.”

This is the second in the series. Read the first here, the second here, the third here, and the fourth here.

Editor’s Note: This project was produced with support from the International Centre for Investigative reporting (ICIR).

Twittter: @fisayosoyombo

In the final episode of ‘Forgotten Soldiers’, the reporter shares his personal observations from his interactions with some of the protagonists of the war against insurgency, plus two fateful events that — if they occurred in separate circumstances — could have rendered him a victim of a bomb blast that killed four people and injured 19.

1 comments

Thank you for penning down the story behind the story. Sometimes people forget that members of the armed forces are actually human and therefore have the same feelings and emotions as the next human. Please if possible make a book out of your findings and recordings so that future generations would be school on this period in the history of Nigeria.