BY ZUHUMNAN DAPEL

In recent years, the naira-dollar market in Nigeria has so far been liberalised twice. The first, in June 2016 and the second, in June 2023. Both moves have significantly contributed to the rapid decline in the value of the naira. If the monetary authority firmly embraces and continues to stick to this option, the strength of the currency will yet again continue to shrink at an accelerating pace.

The fall of the naira is fast diminishing the international (purchasing power of the currency and consequently) buying strength of Nigerian residents. For instance, as recently as 10 years ago, Nigerians schooling or buying foreign education services abroad in the United Kingdom needed roughly two million naira to pay a tuition of £10,000. Today, they will need close to 20 million naira to pay the same school fees. A tenfold increase.

To liberalise a currency is to let the forces of demand and supply of the currency solely determine the value of the currency. The technical term for this in economics is called “floating”. For instance, if Nigerians rush to buy the dollar more than Americans are rushing to buy the naira, the value of the dollar will go up at the expense of the value of the naira. In other words, the value of the naira will fall. Similarly, if there is more demand for the naira by Americans and less demand for the dollar by Nigerians, the value of the naira will rise. It will become stronger.

Advertisement

In this opinion piece, I share my perspectives – grounded in data-driven evidence – on why liberalising the Nigerian forex market (was and still is) a policy error. I also argue that the premise (“to attract foreign direct investment”) motivating the most recent liberalisation is not a compelling one for many observers. Finally, I offer suggestions – short-term, medium-term, and long-term – solutions in dealing with Nigeria’s currency crisis.

When the ‘float’ cleans out the naira

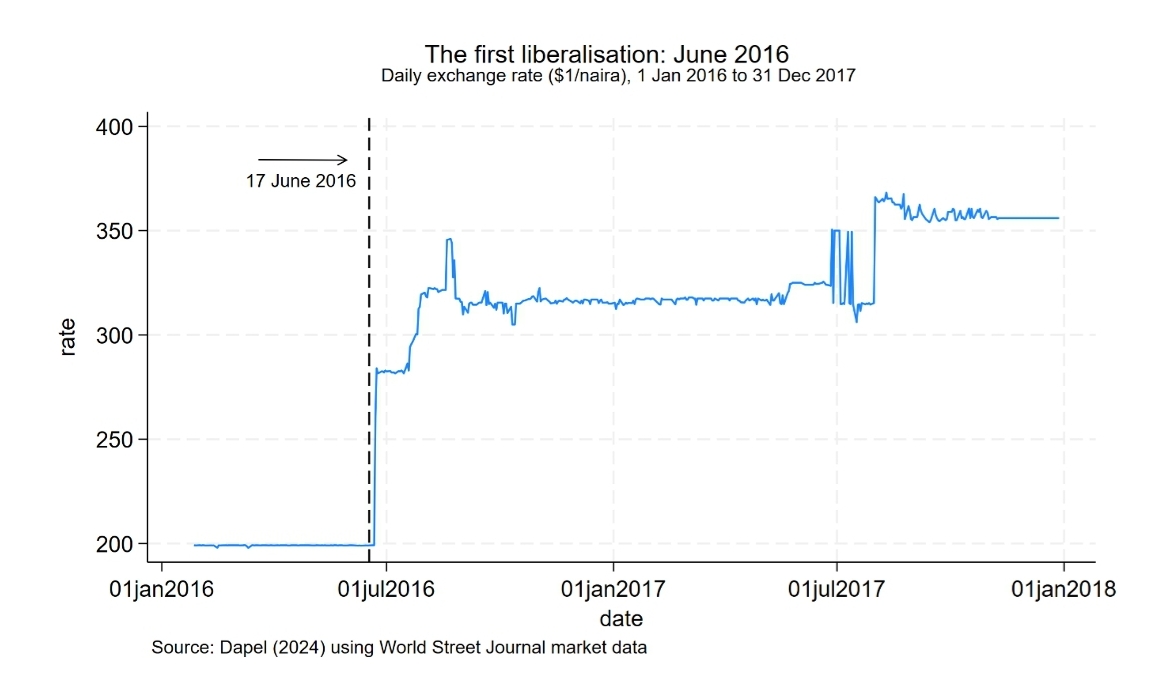

On 17 June 2016, the naira was ‘freed’ by the central bank. But the ‘freedom’ set the currency on a freefall such that within a few months, by the end of that year, it had fallen in value by 60 per cent against the US dollar (see the chart below). Before this, the naira was pegged at 197 to the dollar. The sharp drop in the value prompted the apex bank to rescind its initial forex policy, thus intervening in the market to save the naira.

Advertisement

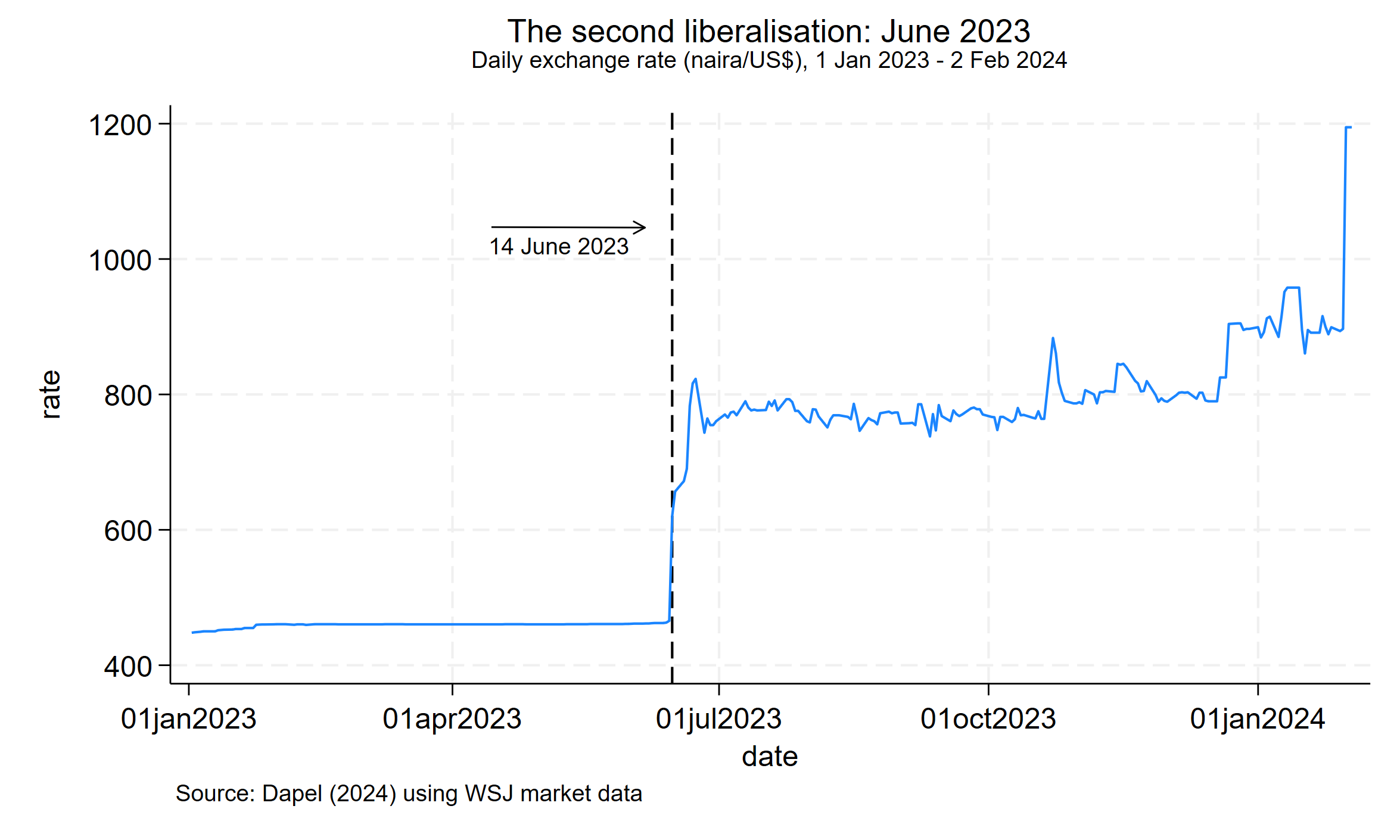

Seven years down the line, on 14 June 2023, the naira was yet again ‘floated’. This time around, after hovering around 400, the naira crashed to about 1200 naira to the dollar as of February 2024. See the graph.

The scarcity, the error, and the fall

Advertisement

When the dollar is scarce – its demand greater than its supply – and you ‘float’ the naira exchange rate, you have automatically placed the naira on a glide path to losing its value. There is no convincing economic justification for floating the naira in a dollar-scarce situation and a fragile financial system for some reason.

The naira cannot compete with the dollar. The United States of America, being the primary supplier of the dollar and as a world economic super-power, has more to bring to the international trade table or the world market stage than Nigeria. Therefore, Nigeria letting its currency ‘float’ or roam about in search of its value in the international market is equivalent to inflicting self-damage. The naira cannot compete with the currencies of world economic giants because these stronger economies, more than Nigeria, bring more economic value to the rest of the world. For example, Nigeria’s daily crude oil output, the country’s major foreign exchange earner, is not sufficient to meet America’s two-hour oil consumption as the United States consumes approximately 20 million barrels a day.

Also, ‘floating’ a currency in an unstable monetary system opens the possibility of speculative attacks on the dollar. Dubious traders will get the dollar at an official rate and sell it through the black market at a whooping premium.

The forces behind the fall of the naira

Advertisement

The increasing scarcity of the dollar and its growing demand in Nigeria are at the root of the collapse of the naira. Why is the dollar scarce in Nigeria? I have identified four contributing factors.

First, falling oil revenues. In eight years, between 2007 and 2014, Nigeria earned over US$340 billion in oil revenues. This figure has fallen to US$110 billion (more than three times) in the recent eight years between 2015 and 2012, thus, shrinking the nation’s capacity to pull in more dollars into its economic system.

Second, in late 2015, the then government through the central bank activated capital control measures such as shutting out access to foreign currency withdrawals and imposing limits on how much cash Nigerians can withdraw using foreign ATMs. These interventions did not pay off as the currency further depreciated. As a result, factories that could not obtain dollars to import raw materials and capital goods shut down and eliminated tens of thousands of jobs. By mid-2016, the economy had fallen into a recession.

Advertisement

Third, foreign investors have been fleeing out with their dollars, draining the system of cash. Within five pre-election and election years (2013-15 and 2018-19), a total of over US$100 billion was withdrawn from Nigeria through the financial services forex utilisation. There is no guarantee that these dollars are coming back given that more foreign companies have recently exited the Nigerian market.

Fourth, the demand-pull effect. Rising inflation in Nigeria is affecting the portfolio behaviour of many income savers given that the rising cost of living weakens the future purchasing power of the local currency. Instead of saving in naira, they prefer to save in dollars, thus pushing up the demand for the dollar. It has been alleged that Nigerians have US$30 billion in savings vainly sitting in their domiciliary accounts across domestic commercial banks. The central bank recently quelled down a public rumour that it intends to convert these deposits from dollars to naira.

Advertisement

Another side of the dollar-demand effect is the rising exodus rate of Nigerians especially to Europe and North American countries. According to World Bank numbers, Nigeria’s net migration pace has been progressively negative since 2014, implying that more people are leaving the country than are entering the country. Tellingly, those relocating from Nigeria to other parts of the world add to the demand for foreign currencies to defray their resettlement costs abroad.

Foreign direct investment is not the silver bullet

Advertisement

Investors move money across borders for one primary reason: to make a profit. While FDI injects the dollar into the host economy, profit repatriation withdraws dollars out of the economy. The latest World Bank figures on Nigeria’s foreign direct (net inflows) investment are negative. This implies that Nigeria is losing more dollars than it is attracting into its economy. Moreover, the proceeds of foreign commercial airlines are still being trapped in the country.

Can the naira be salvaged?

Engineering a revival of the naira is not easy as this will require three cumulative layers of approaches: short-term, medium-term, and long-term solutions.

Short-term solution. Revert to the initial status quo: regulated peg exchange rate policy regime. This can be done within 15 minutes. Before June 2016, the dollar was pegged and sold at less than 200 naira via the official market. The central bank, being the nation’s chief financial regulator, should impose a cap on the dollar price of commercial banks.

Medium-term solution. The primary goal of a central bank is to stabilise prices, that is, exchange rates and inflation. The apex bank will not be effective in achieving these targets if it is not independent of the federal executive branch of government, otherwise, its policies will always be driven by political interests. How do we detect a central bank that is not independent? Two ways. First, if the president of the country appoints a central bank governor from his [the president] region, state of origin or has once served in the cabinet of the president. Second, if the turnover of central bank governors is high, that is, they serve a single term of five years instead of the maximum 10-year two tenures. Nigerian presidents from 1999 to date are all guilty of this.

As a nation, we have always admired America for being a beacon of world economic prosperity. We can learn from them as they have managed to insulate, to a greater extent, their central bank from political interference. Their longest-serving central bank governor (Fed Chair Alan Greenspan) was in office for 18 consecutive years, serving under five presidents, both Republicans and Democrats. He was kept there because he was very good at the job before he later resigned.

Long-term solution. Import substation. Revamp four key sectors to substitute for the importation of food, clothing/footwear, building materials and pharmaceutical products. These are heavily consumed goods in Nigeria, gulping a significant fraction of the nation’s forex via imports.

Dapel can be reached via Twitter: @dapelzg

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment