One day in 1997, the late Austin Akosa, along with three other men, visited our office to seek publicity for an initiative he was fronting. Akosa, a former West African Football Union spox, as I remember, was seeking to create a welfare platform for former footballers down on their luck. During an interview session with the sports desk, in which I sat uninvited, he tried to explain his ideas of the platform.

From what I remember, his targets were corporate organisations and affluent, sports-loving individuals. One of his interviewers, seemingly alarmed that the sports authorities were excluded from his plans, sought to know why. Specifically, the interviewer named the Nigeria Football Federation (nee Nigeria Football Association), arguing that it was its job to provide — without fail– relief for internationals in post-retirement financial distress. It is a view that was popular then and still is.

Akosa said it was not possible for the football body or sports ministry to do what the interviewer suggested. First, he said –correctly, in my view– that internationals were paid allowances (certainly not anywhere near the range of what is paid these days) for their services. Second, he told the interviewer that the number of ex-internationals, including those with caps in single digits, would make this impracticable. Another of his interviewers chipped in with the line that given that internationals brought glory or fame to the country, they deserved to be put in a special category deserving of something not far from nannying. He still rejected the suggestion.

After Akosa’s departure, his interviewers and I continued the conversation over drinks across the road. I said I was in agreement with Akosa. It sounded hard-hearted to them. While I did not (and still do not) think the Nigerian society offers strong enough safety nets against adversities, including the health-related, I said I did not think (still do not) that the job of getting every distressed former sports star out of life’s jam was that of the sports authorities (read government).

Advertisement

I gave cited Kenny Sansom, formerly of Arsenal, who slipped into financial distress on account of his flaming affection for liquor and gambling, adding that I did not remember the English FA hurling cash at him or others in a similar situation. I also did argue that the Nigerian Railways Corporation, an epitome of institutional cold-bloodedness, had staff who worked their butts off and were as patriotic as any Nigerian on two legs, but never got what was due to them let alone lashings of post-service compassionate gestures. They were unpersuaded, so we moved on to other things, notably the liquor on offer.

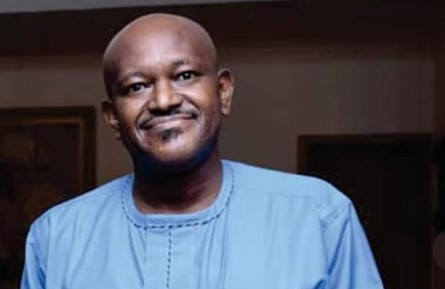

Former sportsmen are not the only people the media recommend for special treatment. Case after case is made for Pa Taiwo Akinkunmi, the designer of our national flag, who was placed on “life salary” by the government of President Goodluck Jonathan. A social media post I saw a few years back had the photograph of his home, with a chapped coat of paint. The poster called on the government to get the house repainted for what he did and got enormous support in the comments section.

Akinkunmi’s entry won the competition for the national flag design while he was a student in England. He earned a cash prize of £100, hardly a mind-blowing sum at the time. He returned to Nigeria and had a career in the civil service, for which he must have been paid a gratuity and is receiving pension.

Advertisement

I am not against compassion, but demanding that the government must, as a rule, directly pick up the tab for those who had been paid for their services because they are prominent is what I struggle to understand. At every level, there are great teachers, for example, many of whom are in the dumps for one reason or the other and without media cheerleaders.

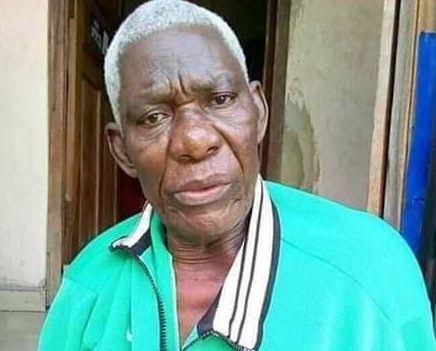

I was nudged to write this by the viral photo of the ailing former national goalkeeper, Peter Fregene, and the strident view that it is the sports authorities that have the responsibility for funding the restoration of his health. I need to repeat that I do not object to compassion and Fregene is deserving of such. But the way the conversation is framed is what I find unagreeable. A friend, who posted the photo, raised the possibility that he is being owed, the reason he is unable to fund his treatment. That, if true, would be evil.

But evil of that nature, we all know, is what the sports authorities do for fun. Many former sports heroes, especially those who go into coaching and administration, are owed salaries and severance benefits for long spells, something the media need to make a sustained campaign issue, with a focus on specific offices/officials responsible for the ill-treatment. Most people are just an event away from crisis and even if we are paid. So, what next? Clubs, for which footballers were cult heroes or out-and-out legends and paid for their services, say, be asked to set aside revenues for distress packages? To how many people and what are the criteria for choosing, if choices have to be made?

A career in sports, including at the professional level, is a short one. For the luckless, it can be mini-skirt-short (pardon the naughtiness) and in reality, very few make it into the big time. Even in the big time, there is no guarantee of financial success. Sports stars of yore, of course, did not earn the eye-watering sums earned today. But I do suspect they earned more than most people, but over a much shorter time. The big earnings come early in their careers, imposing the need to manage it in a way that ensures it lasts a long time or a lifetime.

Advertisement

Career brevity, possible injuries and lavish lifestyles put those earnings at high risk. One of the things the media and public should be campaigning for is a culture of early saving and investment, so that the incomes can grow over time and provide returns. For some years now, Flykite Productions, organisers of GOtv Boxing Night and of which I am part, have organised sessions for boxers on various topics, including financial management. Those sessions, part of boxing development, are backed by MultiChoice Nigeria. I hope beneficiaries are taking learnings from them.

A campaign for saving/investment culture is more important, given that lucrative second career opportunities, such as in broadcasting, are thin on the ground, unlike in better developed societies. I do not have enough familiarity with the local scene to say with authority whether or not sports people have life insurance or permanent total disability insurance to protect future income. If they do, great. If not, the media should point those in sports and those with the desire to go into the industry in that direction.

No plan is fail-safe and we have seen sports people being targets of scammers or victims of bad financial advice. We can similarly advocate for the creation of systems to limit exposure to such. They will never be eliminated. It is also important that we target a campaign for young sports people to seek to acquire skills and formal qualifications either alongside their sporting activities or once their sporting days are over, for future deployment.

That way, they are better sandbagged against a wave of misfortune as well as bringing about a reduction in demand for government intervention. While these are too late for those already retired, they are useful to those still active. The contributions of soldiers, policemen, firemen, teachers, journalists and others to society may be less headline-grabbing, but are not inferior to those of sportsmen. What we need as a society are sturdier safety nets for all. It is a no-brainer that this is not going to be a popular view.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment