Especially for persons not familiar with the etymology and morphology of mkpurummiri and akuskura, their very sound suggests something demonic, beings designed to torment the souls of humans. But they are indeed substances Nigerians have woken up to in recent times as being highly addictive. The former first made its debut in the country not long ago in the south-eastern zone from where it derived its local name.

A Methamphetamine or Crystal Meth original, mkpurummiri has a chequered history of its own. Developed in Japan after the First World War, meth was officially and unofficially abused in the course of the Second World War when it was administered to Japanese soldiers and fighter pilots who were sent on suicidal assignments called Kamikaze. Its relevance continued even after the hostilities as it was used to treat obesity and mental states like depression. As the side effects were becoming too apparent, however, it was gradually side-lined and, later in the 1970s, outlawed altogether. True to the nature of addictions and the volatility of the market forces of hard drugs, the ban could not obliterate the substance. It only went largely underground for some time. The grand re-entry came in the 1990s when Mexican drug cartels picked interest in it and became hugely responsible for the globalisation of its production and trade. It has since been classified among the Schedule II of drugs in the International Drug Control Conventions, adequately described as “drugs with a high potential for abuse, with use, potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence.” And to bring the tons of meth-related problems closer home, a laboratory for the manufacturing of the product was reportedly established in Nigeria six years ago.

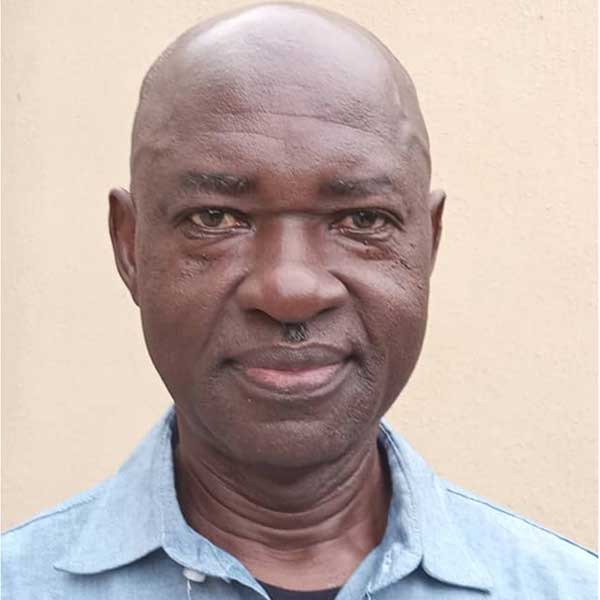

I had a disturbing encounter two weeks ago in a village in Edo State. A plastic bottle containing some whitish liquid was pierced from the cover with a straw or two on top. In my ignorance I wondered out loud when people started drinking palm wine that way. A young man then graciously educated me about mkpurummiri, a substance known so far to be consumed mainly by Igbo youths, and which has been identified as one of the major obstacles to arresting the insecurity crisis in that section of the country. It then dawned on me that the patronage of illegitimate consumables cannot be localised or restricted for long. With aggressive marketing, their spread is inevitable. An explanation given last year by Mr Femi Babafemi, spokesperson of the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA), is both sobering and concerning. According to him, “It is a very addictive stimulant that renders the user hyperactive and prone to destructive tendencies, which at the extreme do not exclude suicide or homicide at the slightest provocation and without a feeling of remorse.

“As a stimulant, it has powerful euphoric effects, similar to those of cocaine. Meth typically keeps users awake, depriving them of sleep. Its use and abuse also carry acute health risks including high blood pressure and cardiovascular-related illness. Aside from being unable to sleep and being violent, users exhibit anti-social behaviours arising from paranoia and hallucination. The drug takes a toll on the physical look of its users. It typically makes them look older and their faces prone to acne. Sometimes, excessive use leads to damaged gum and teeth, commonly called ‘meth mouth.’ What is most frightening is that meth addiction is one of the most difficult to treat because no drug can cure it, except by behavioural therapy, which at the moment is not readily available in the country.”

Advertisement

The woes associated with mkpurummiri, of course not specific to it, and the predicament the nation is faced with as a result are now being compounded by the recent rude announcement (certainly not new entry) of akuskura, a psychoactive drug that poses not only a threat to public health but a unique challenge to drug policy. This is why. It is in the form of herbs, intricately laced with cannabis and tobacco and is consumed either as liquid or powder. Packaged as a remedy to sundry complaints like catarrh, headaches, weak erection and evil spirits, this substance also known as kuskura, akurkura or kurkura-all derivatives of its Hausa root –is very affordable and accessible, peddled mostly by herbalists and religious chemists.

The instant appeal it presents to Nigeria’s teeming despondent and increasingly vulnerable population is simply too difficult to ignore. Disabling consequences like unprovoked aggression, acute psychosis, unusual agitation, seizures, violent dispositions, irregular body movement, muscle contraction and dependency prospects have not dissuaded its lovers, many of whom are proud, open users, found mainly in the western and northern regions of the country. When a record consignment of over 7000 bottles of akuskura was confiscated by NDLEA along the Abuja-Kaduna Expressway, the drug was promptly added to the list of enemy opiates. The exorbitant price tags on controlled stimulants like codeine only serve as incentives for its continued galloping attractiveness and consumption.

If only these consumers can access the admonition by Frank Tallis, accomplished British author and clinical psychologist. As he put it, “At first, addiction is maintained by pleasure, but the intensity of the pleasure gradually diminishes and the addiction is then maintained by the avoidance of pain.” Most times, it’s difficult to determine the exact moment the shift from enjoyment to escapism occurs. Anytime it happens, the outcomes and their tolls are immeasurable – at personal, family, organisational and societal levels.

Advertisement

The overview provided by the Africa Regional Office of the World Health Organisation (WHO) on its website on the growing calamity is unnerving and scary: “Substance abuse refers to the harmful or hazardous use of psychoactive substances, including alcohol and illicit drugs. One of the key impacts of illicit drug use on society is the negative health consequences experienced by its members. Drug use also puts a heavy financial burden on individuals, families and society. The evolution of the complex global illicit drug problem is clearly driven by a range of factors. Sociodemographic trends are influential such as the population’s gender, age and the rate of urbanization.

“Cannabis remains the most widely used illicit substance in the African Region. The highest prevalence and increase in use are being reported in West and Central Africa with rates between 5.2% and 13.5%.Amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) such as ‘ecstasy’ and methamphetamine now rank as Africa’s second most widely abused drug type.” This gory picture becomes even more worrying in the midst of the hunger and abject poverty that have further subjugated a chunk of the populace.

“Drugs are a waste of time. They destroy your memory and your self-respect and everything that goes along with your self-esteem” is a statement made by Kurt Cobain, lead vocalist and guitarist of American rock band, Nirvana, who took his own life in 1994 at the age of 27 having lost a prolonged battle with drug addiction and depression. Can there be a better reference point or tragic hero in the ongoing efforts to stem the tide of reckless, snowballing abuse of outlawed materials like that young music icon and similar others spread across dispensations and locations?

The assertion in T. S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral that people learn little from the experiences of others is not comforting here. But fight on we must as the alternative is too costly. Governments, relevant agencies, non-governmental institutions, religious bodies, other private entities and well-meaning individuals should break away from lethargy and prioritise the quest to rid the country of the craze to ‘get high’.

Advertisement

Dr Ekpe is a member of THISDAY Editorial Board.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment