By Geoffrey York/The Globe and Mail

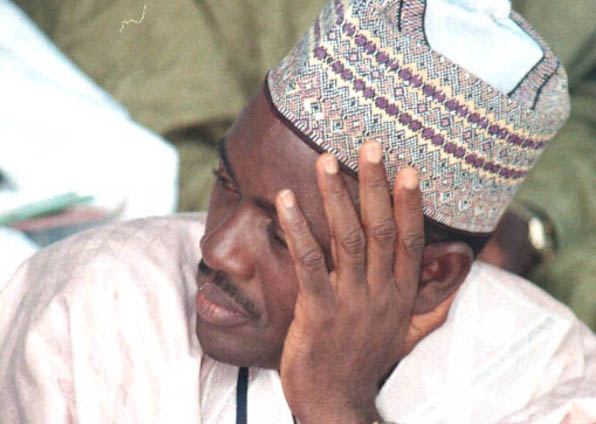

With a crucial election just nine months away, Mr. Jonathan’s opponents are ridiculing his handling of the kidnapping of more than 200 schoolgirls. “He needs help,” scoffs Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso, the influential governor of Kano state and a possible challenger to the president in the February election.

Mr. Jonathan responded far too slowly, allowed the crisis to turn into a “mess,” and failed to protect the country, the Kano governor says. “He wanted to sweep it under the carpet like nothing happened.”

Advertisement

It’s a common sentiment in northern Nigeria, where many people are resentful that a southern, Christian president might seek re-election in a divided country where northern Muslims are impatiently awaiting their turn in power.

Yet Mr. Jonathan might still keep the presidency next year if he decides to run again. In much of the country, he retains significant support. When Boko Haram last month killed dozens of people in an impoverished neighbourhood of the capital, Abuja, he visited the bomb site and impressed the locals with his sympathy and emotion. In interviews near the bomb site, people praised him for doing everything he could to safeguard their neighbourhood – even though a second blast hit the same street just two weeks later.

In some countries, the failure to solve a protracted kidnapping of more than 200 girls would be politically disastrous, destroying a president’s future election prospects. The crisis was compounded by Mr. Jonathan’s failure to speak about it publicly for more than two weeks after the girls were abducted, and his failure to visit the kidnapping site at Chibok in northeastern Nigeria, despite reports that he would travel there last Friday.

Advertisement

But in Nigeria, where ethnic and religious divides are deep, and where the economy is still the crucial issue for most of the country, the election could be determined by many other factors besides the Boko Haram crisis. The president’s base of support in southern Nigeria, especially the oil-rich Niger Delta region, could help him win re-election. Then there are the covert factors – election cash, police muscle, state resources – that will always favour an incumbent in Nigeria.

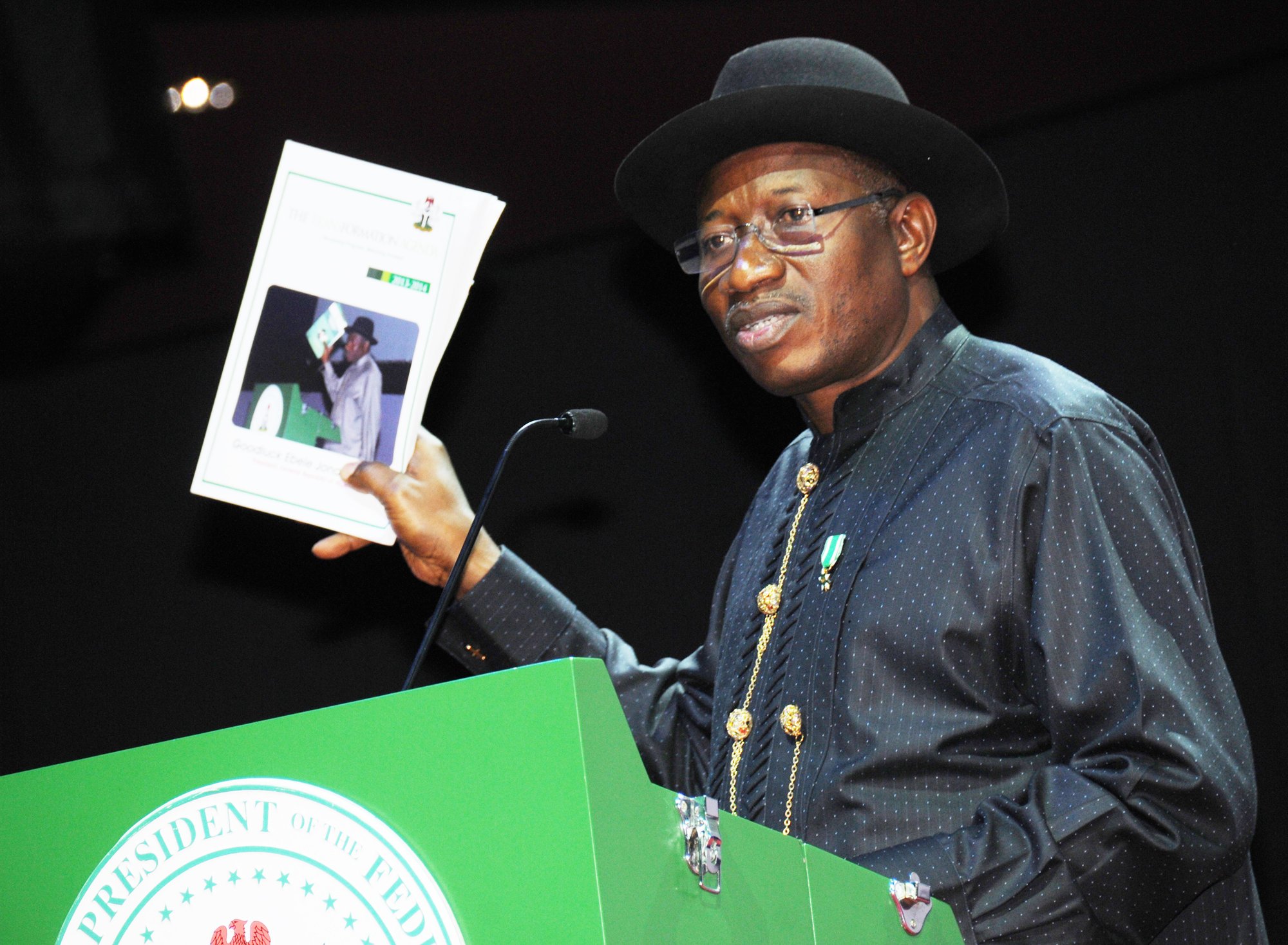

Mr. Jonathan, one of the first civilian leaders of a country with a long history of rule by military and ex-military men, is a soft-spoken man with a modest background and humble image. The son of canoe-builders in the Delta, he studied zoology and held a mid-level civil-service job. He ascended to the governor’s job when his predecessor was impeached, and then was unexpectedly chosen as Nigeria’s vice-president. He became the accidental president just two years later, following the death of the president, Umaru Yar’Adua.

In the current Boko Haram kidnapping crisis, Mr. Jonathan is hampered by a fragmented political and military system. His authority is weakened by Boko Haram sympathizers in the northeastern governments, and high-placed dissidents in his own administration – some of whom are suspected of leaking his travel plans to scuttle his visit to the kidnapping site.

In a country where northern insurgencies were often brutally suppressed by the Nigerian military in the past, and where the army is still guilty of human-rights abuses in its fight against Boko Haram today, Mr. Jonathan cannot rely on a purely military solution to the kidnapping of the schoolgirls.

Advertisement

“He’s trying to tread very carefully,” said Ken Saro-Wiwa Jr., a senior special assistant to Mr. Jonathan. “You don’t rush in with a hammer. Every action has a reaction.”

With stacks of daily security reports and back-channel sources of information, Mr. Jonathan is more connected to the kidnapping crisis than his critics realize, Mr. Saro-Wiwa said.

“Jonathan’s style is baffling to many people but he’s emerged through some very trying and difficult processes. He is difficult to read. But he has spent 14 years in government and knows a trick or two. When the pressure is on, he steps back and then acts when you least expect it. ‘Sure and steady’ is his motto.”

One of the biggest problems, he said, is the lack of clear data from northeastern Nigeria, even on basic questions such as the number of schoolgirls who were kidnapped in Chibok last month. No clear number exists. “What’s known in this case is relatively little, which is astonishing,” he said.

Advertisement

2 comments

Yes the President has been undermined by the Boko Haram insurgency, but it has at the same time helped his political prospects in 2015. This is Nigeria and we know the power of the “intangibles” of ethnicity and religion. These who want to use religion and ethnicity to come to power have inadvertently handed Jonathan the Presidency again in 2015 on a platter. This is because two can play at the game. The people for him, based on these two factors are more than those who are against him. We are all Nigerians and can read between the lines.

These parasites, who want to reap but cannot sow will meet their political and hopefully final economic “Waterloo” in the looming encounter with the hitherto “shoeless” son of the Otuoke canoe carver, and that will be the political lesson of 2015.

Classic presidential PR job. Even these Oyibo people practice cash and carry journalism???