The evolving sociology of vote-buying in the Nigerian political milieu once again dominated public discourse in the aftermath of the recently concluded gubernatorial election, and its attendant dents on the integrity of the electoral process.

There are many factors at play when it comes to determining the credibility of the electoral process. The presence or absence of the following phenomena; political thuggery (leading to intimidation of political opponents and consequently, leads to disenfranchisement); the level of perceived neutrality of the umpire (the Independent National Electoral Commission, INEC); the safety of INEC staffers (including the ad-hoc ones); voters’ inducement with money (popularly referred to as vote-buying), are some of those factors, that determine whether or not, an election is credible.

In July 2018, I was a member of a three-man team that covered the Ekiti governorship election live for my media platform and I saw how some voters “hawked” their rights to freely choose who succeeded Governor Ayodele Fayose, who was then rounding off his “second term” in office. While trying to sort out my accreditation at the NUJ secretariat on the eve of the election, I watched with my two naked eyes at some strategic locations within the government house in Ado-Ekiti how people gleefully queued with their PVCs to mortgage their future for a paltry sum of ₦3,000. I learnt it was ₦4,000 earlier in the day before we arrived but by dusk, it has come down to ₦3,000 maybe for reasons bothering on the interaction of the market forces of demand and supply. That (the transaction) was with the understanding that they would vote for a certain candidate they already knew, dictated by the buyers of their votes. The video went viral at the time.

While that was happening, a counter-campaign rented the street of Ado-Ekiti, with the slogan: “D’ibo kò ṣe’bẹ; ṣe’bẹ, kò j’iya fún ọdún mẹrin“, which could roughly be translated to “sell your vote for a mesh of porridge (today), and live through the next four years in (socioeconomic) hardship”. That was obviously sponsored by the then opposition party in the state, All Progressives Congress (APC). As we (reporters, local and foreign, who came to cover the election) watched in bewilderment, hardly did we know that the other party, APC, were planning a “mega offer” to be unveiled much later in the evening for those who were ready to play the game. Who wouldn’t be ready to play the game anyway as it was becoming a new normal? Sources, all of whom were parties to the transaction that took place late through the night till the early morning of the day of the election, told me then that they each got as much as ₦10,000 each rather than what (offer of a paltry sum of ₦3,000) we witnessed in daylight. They were so happy because, they obviously, “never have had it so good”.

Advertisement

At the end of the day, the candidate whose party offered the highest rate per PVC holder, as a matter of course, won the election. So, it was a case of a buyer out-buying the other. And another off-cycle election in Osun state, which came about two months after, did not go without reported incidents of vote-buying either. It has been the pattern even during the presidential election as each local political chieftain does that to garrison his territory and safeguard his political relevance. They adopt different strategies. While some visit the seller in a nocturnal arrangement, where money exchanges hands, others come to the polling unit to induce, in hushed tones, those who are already on the queue in readiness for vote-casting. So, it is a matter of ‘Cash ń Carry’.

Over a fortnight ago, as the people of Ekiti state were preparing to elect the successor to Governor Kayode Fayemi and the custodian of their political destiny for the next four years, on Saturday, June 18, 2022, there was this debate among some of my friends and colleagues both physically and online, on the degree of readiness of the INEC, and its capacity to deliver a free, fair, and credible election. That was where the inspiration for the last two weeks’ article, ‘How independent is INEC?‘ came from.

Within me, I was thinking about whether or not they realise that INEC cannot single-handedly deliver a free, fair and credible election especially in this clime where everyone seems to have a different notion of what, and what constitutes a free, fair and credible election. An election is only free, to some people, if the result is in their favour. Anything to the contrary, according to them, is not free, fair and credible, and must, therefore, be thrown into the trash can.

Advertisement

To conduct an election that ticks all the boxes, for instance, the process must be in accordance with the provision of the electoral act and other relevant laws. There must be a provision of adequate security of lives and properties of the electorates in addition to ensuring the safety of electoral officials and materials before, during, and after the election. But we all know that INEC does not have a troop in its commands. There are several other stakeholders, apart from the electoral body who have certain responsibilities among whom are the security agents, politicians, and the electorates, just to mention but a few. The conduct and delivery of an election that would be high on integrity, and credibility, therefore, depends on all hands being on deck.

The end justifies the means, for those who are bent on ensuring that the result goes their way at all costs. This is because they are ready to do anything, including deploying thugs, without INEC being able to do anything unless the security agents are on top of their game. The election can only be violence-free if all the candidates agree to it that whatever the outcome of the process is, they will abide by it. There is bound to be post-election litigation, challenging the credibility of the result, where desperation is the only rule, the contestants obey. The election can be placed at par with those that could be described as credible if only the politicians are unable to use any means to sway the voters, as they make their choices. But you and I know that INEC is ill-positioned to ensure that, at least, for now.

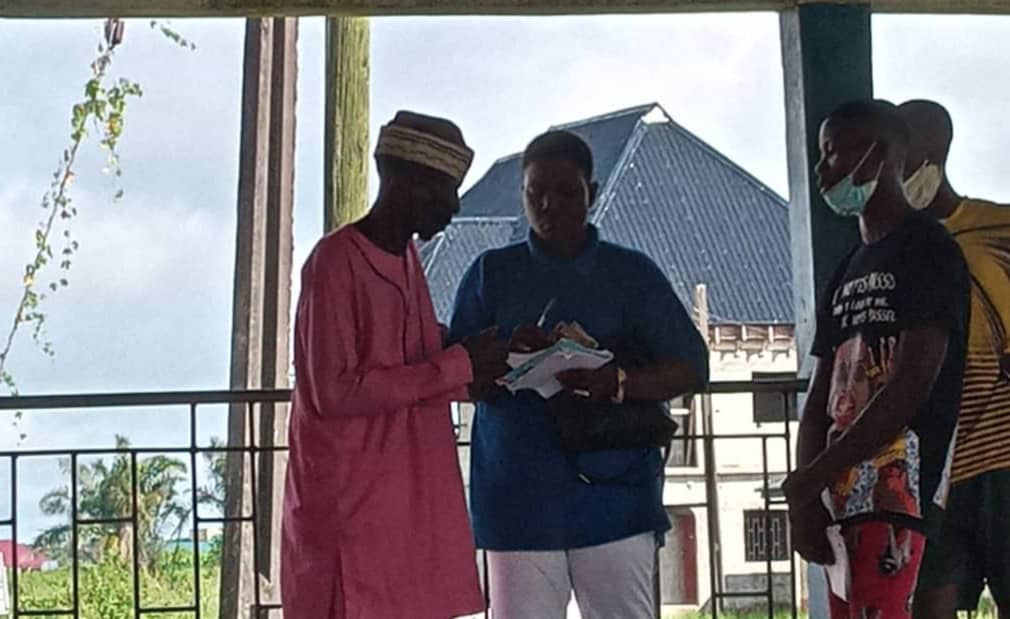

Unfortunately, however, that is where the issue of vote-buying comes in, as a matter of serious concern, in our electioneering. There seems to be nothing INEC can do to stop it. As odoriferous reports of rampant vote-buying oozed out of Ekiti, last Saturday, I began to wonder if the phenomenon has come to stay in our polity for good. Has it come to stick with us like houseflies tend to be ubiquitous, wherever palm wine is being served? It becomes very painful for me to admit that seeming reality. I was reliably informed that it was even the voters that were scouting for buyers in Ekiti – a state with one of the highest rates of literacy in Nigeria. The rates at which they bought and sold votes, according to the reports, ranged between ₦3,000 and ₦10,000 per voter.

Meanwhile, we complain of our electoral process being so heavily monetised that it would take someone who has had access to the public treasury and has helped himself to an amount that can last an average Nigerian family for 10 lifetimes to be able to contest and win an election in Nigeria. That is the reason it appears, that whenever these politicians find themselves in positions where they have access to the public treasury, they steal as much as they can, to safeguard their long-term political relevance. The most unfortunate part of it is that the cycle of stealing continues because, anyone who spends money and wins the election next year, for instance, would have to recoup first, the investment and then proceed to steal more in readiness for the next election. And nobody has an inkling as to the ROI (return on investment). It could be ₦5 million on every ₦1 spent.

Advertisement

That means our commonwealth will be at the mercy of such a socioeconomic vampire from 2023 till 2027 when another round of vote-selling opportunities will come around. They must, therefore, steal enough money to out-spend their prospective opponents, to out-buy them, in the next election. Tell me how possible it is to gatecrash into the close-knit circle of the political elites that have held the country by the jugular, for decades, through this institutionalised heisting of our common patrimony to perpetuate themselves in power? It would be the more difficult, if and when it is the people who have the power to retire them with the instrumentality of their PVC, that are now the ones chasing them (the vote-buyers) up and down. That is what you get when poverty is weaponised.

I read in the news that, the police and the EFCC had their men on the ground in Ekiti to curb the ugly advertisement for our democracy. A good move, if you ask me. But remember, men of the law enforcement agencies are not, in any way, immune to weaponised poverty. So, what becomes of those (buyers) who were unfortunate to be caught? Do not stress yourself. Your guess is as good as mine. A phone call from “above”, would set them free in a matter of hours, if the suspect did not have enough on him again at the point of arrest to purchase his freedom on the spot.

The most embarrassing aspect of the sociology of vote-buying in Nigeria is the prevalence of poverty in the land, which has now been weaponised against Nigerians such that they have a price for their destinies, renewable every four-year, with an amount as paltry as ₦3,000. The excruciating effects of poverty have prevented most Nigerians from realising and appreciating the power of their respective “one-vote”. Let’s do a bit of arithmetic here. Those who collected ₦10,000 before voting for a particular candidate, without knowing it, had sold each day of the next four years for as low as ₦6:84 kobo, those who collected ₦5,000 had done something similar for, nothing more than ₦3:42 kobo per day. Those who could not negotiate for an amount above ₦3,000 have inadvertently sold their next four years at the rate of not more than ₦2:00 for a day. Yes. It was that cheaply priced, no thanks to the abject poverty that walks on all four in the country.

The issue of monetization of politics in Nigeria has, over the years, constituted an obstacle to many qualified candidates being elected into office. We have, in government, people who are rich enough to buy their ways into offices for which they’re intellectually least qualified. And those who are intellectually qualified get blown out of the water by the “money-miss-road” billionaires who are either in the race themselves or are willing to sponsor a stooge. That very unpalatable reality has made a mockery of the “not-too-young-to-run” bill, passed into law by the 8th national assembly, lowering the respective age bar for people who want to contest for any political office in the land.

Advertisement

Many people have been clamouring for the enactment of another one, “Not-too-poor-to-run”, to complement the former so as to minimise the degree of disenfranchisement occasioned by monetization of the process. How would that function? They argue that the fees for the Expression of Interest (EoI) form should be made more affordable for people, if not free, so that the issue of exclusion from the process can be minimised. We were all living witnesses to how the parties priced their nomination form fees for various offices, beyond the affordability of an average Nigerian. They ensure that the amounts fixed for each of the offices are way beyond what an average Nigerian, in each of the age categories, can afford unless there is a financial “Sugar Daddy” somewhere to bankroll it. It, therefore, becomes available for those whose families are rich enough to be able to procure one for them or those who are willing to be puppets in the hands of political godfathers. Meanwhile, the negative impacts of politics of prebendalism on our national development are visible enough for the blind to see, and audible for the deaf to hear. We must therefore join hands in eradicating vote-buying from among the elements of our political culture.

But we cannot talk about the evil of the monetised political process in Nigeria, without talking about the roles the masses, themselves, play in enabling it. No matter how brilliant your ideas of governance are, nobody would be ready to listen to you or vote for you if you do not give them Shishi —apologies to a former governor of Anambra state, and the Labour Party’s presidential candidate for 2023 general election, Peter Obi. Even in cases of an indirect election where delegates who are deemed more enlightened than most of the party members vote for the emergence of the party’s flag beaters, they demand money before voting. As a matter of fact, it is like a season of harvest for them, whenever they organise their congresses, to (s)elect party flag bearers. They now, reportedly, pay in dollars. It is a sad, but true, case. That is who we are, that is how we are psychologically wired, that is how we roll.

Advertisement

After thinking very deeply about the situation, I shudder to ask; has the phenomenon come to stay with us? Are we resigning to fate, until it fizzles out, like its siblings – ballot box-snatching/stuffing, figures manipulation, political assassination, and use of thugs and security agents to intimidate opponents’ supporters?

Abubakar writes from Ilorin. He can be reached via 08051388285 or [email protected]

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment