Ruined towns, desolate homes, wasted farms, shattered lives and loved ones hacked to death, they lost it all; but they are now far away from their ancestral land where Boko Haram established a reign of terror. They perch on mats in rickety and tattered tents, some in open places, struggling to mask the pure pains and grief which the sweet memories of the past bring. These persons at internally displaced persons (IDP) camps littering the corridors of Maiduguri, Borno state, spoke with TAIWO ADEBULU about their desire to go back home, but home is nowhere safe.

Years after the invasion of their homes, the massacre of loved ones, the torturous exile through the thorny bushes of the savanna under the midnight gloom and creeping through the shadows of caves from the crack of dawn, the memories are still very fresh, even in the minds of the little children who gnashed at every fruit and leaf to sustain the long walks – many of them ravaged by rashes. Without a map and compass, in small groups, they thundered through the whispering darkness to wherever instincts led them. Some were captured in the bush, some killed, and some even died, while the lucky few made it to the state capital.

Once upon a time, the towns bloomed with agricultural products while the farmers frolicked in prosperity after every bountiful harvest. But with the incessant attacks on their homes and means of livelihood, they witnessed the tragic collapse of that dream. Like other states in Nigeria’s north-east, the Boko Haram insurgency which began in 2009 has wrecked havoc on Borno where it began. The one-time home of peace metamorphosed to a theatre of war.

HAUNTING MEMORIES OF THE PAST

Advertisement

It had clocked four years and three days, Bukar Lambari recalled precisely the attack on Bama by armed insurgents which left scores of soldiers dead and residents slain in their hundreds. The heavy echoes of assorted guns sent shivers down the spines of residents as they dissolved into the bush – no one waited for another. Within hours, the town was reduced to dust and a new regime took over.

“It was around 5:30am and I was in the mosque praying,” his voice effortlessly calm and compelling.

“The fleeing soldiers told us to leave the town because Boko Haram fighters would kill all of us. We all ran into the bush. I spent two days in the bush with two of my neighbour’s children and one biological child of mine; some spent 10 days, some five months before they got to Maiduguri. Some people hid in their houses and they could not go out for five months. Till date, I have not seen my wife and other six children.”

Advertisement

But the 60-year-old wouldn’t let that weigh him down because he presides over people who have worse stories to tell. At the Dalori IDPs camp one, where he is the chairman, he got married to Hauwa, a 30-year-old woman.

Jumai Bukar was lucky to have been whisked away by her cousin when women were being abducted and hauled into vans, while the men were gunned down at first sight. The divorced mother of seven escaped into the bush with her children.

“We spent four days in the bush. When we get to a village, the inhabitants will force us to leave after resting for a few hours. They feared that if they accommodated us, they might be attacked to,” she said.

21 DAYS IN THE CAVE OF DEATH

Advertisement

When the ray of the sun pierced the cloud towering above Bayandutse, a town in Gwoza local government area of the state, on June 2, 2013, insurgents in military camouflage stormed the town and like bats out of hell, they overran the town, killing every creature in sight.

“My 31-year-old first son was slaughtered,” John Gwamma, a retired officer of the State Security Services, winced. “I lost my sister and grandson. Many people were slaughtered like goats; our women and girls were abducted.”

At the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) site IDP camp in Wulari-Jerusalem area of Maiduguri, which has become home to thousands of displaced Christians from Gwoza, Chibok, Damboa and Kukawa local governments, Gwamma is the camp chairman.

His parched lips quivered at every word; his eyes rested on the reporter’s notepad.

Advertisement

“When they came in military uniform, we were very happy thinking they were soldiers who had come to save us from Boko Haram but we were wrong. People took to their heels after realising who they were; some ran to Cameroon,” he said.

“With a small group of people, I spent 21 days in a cave in the Mandara mountains, surviving on water from the stream and fruits. When the insurgents started climbing the mountain, we escaped in the night around 1am and trekked to Madagali in Adamawa state. From there, a good Samaritan dropped us with his truck at Michika.

Advertisement

“While we stayed briefly at Michika, Boko Haram fighters attacked the town and people fled in different directions. When they ask you to become a Muslim, if you refuse, you are slaughtered. In 2014, Red Cross linked me up with my wife and children who had fled to Cameroon. I have really suffered.”

CHILDREN OF WAR

Advertisement

You will see them in small groups, with small bowls clutched to one hand, bare-footed and in tattered, dirty clothes begging for alms to survive. They live, grow and survive in the streets. They are known as almajiris. They’ve become a permanent feature of Maiduguri. With depleting aids to the camps, their parents have no choice but to let them go out since they cannot cater for them.

Advertisement

“Seventy-five per cent of the children here are not going to school. They are just roaming about, “ Gwamma said. “Then, UNICEF started a psycho-social support programme in form of informal education to make the children forget the trauma of the past and become normal again. During the programme, we noticed some disturbing trends. You will ask the children to draw something and they will draw guns. They say they want to revenge the death of their parents because they were killed in their presence.”

In an interview with Fatima Akilu, executive director of Neem Foundation, a non-governmental organisation working with victims of insurgency in the state, she said there are a growing number of children-led households which is as a result of the insurgency. Fatima said a lot of children within the camps are without parents or guardians while they fend for themselves. She added that some of the female children were being sexually exploited in exchange for food.

“We provide a wide range of psychological services for the IDPs. They have been traumatised by their experience and they are living out of their communities and their homes and we provide comprehensive psychological assessment, interventions and treatments. We do therapy. We have a team that looks at children’s trauma, children that have been affected by the insurgency; and in Maiduguri, we have about 700 recipients and these are young children who have spent time with Boko Haram fighters in Sambisa forest and they’ve been rescued. We provide them with multiple services, psychological and social support,” Fatima said.

“Without engagement, these young people will continue to experience trauma and other behaviours associated with their captivity. We work on their identity, ideology as some of them don’t understand that Nigeria is a country. We also work on issues of nationalism, what citizenship means, what the country represents. When they first came to us, they said they had their own country and state in Sambisa. Most of them came from very poor communities that don’t have any form of government presence.”

THE BATTLE WITH CHOLERA

Aside malnutrition, the children at the El-Miskin camp are battling with a myriad of health challenges. There was a cholera outbreak at the camp and the children were the worst hit. At one of the medical facilities where the children with severe cases where kept, the children lay on beds waiting to be transferred on a tricycle to a treatment centre.

“We are battling with cholera due to poor hygiene of the displaced persons,” Abubakar Waziri, a nutritionist with Action Against Hunger, told this reporter. “As of now, it’s about 40 per cent. We’ve managed the cases of severe acute malnutrition. Some of them have recovered and discharged. The parents are cooperating with us.”

Mubarak Hamman, a medical doctor with Medecins du Monde, an international medical organization at the camp, said children with severe cases of cholera are being stabilised and referred to treatment centres.

A day after this reporter visited the camp, Haruna Mshelia, commissioner of health, declared an outbreak of cholera in the state.

“This official declaration has become important to the enable state, partners, and NGOs to mobilise adequate resources for a timely and comprehensive response to the outbreak which presently concentrates in Madinatu and El-Miskin IDPs camps and Bolori ward in Maiduguri and suburbs,” the commissioner said.

“I WANT TO GET WELL AND RETURN TO SCHOOL”

The memory of the insurgency has wrecked havoc on 32-year-old Robben Joseph, who was a JSS 3 pupil of Government Day Secondary School, Ngoshe town, Gwoza local government area when the insurgents attacked during school hours on June 26, 2014. The orphan, who couldn’t bear the suffering and trauma of the massacre he witnessed while running to the mountains, resorted to drugs until he smoked a rubber solution that drove him insane.

“They came with cars and motorcycles. I saw them, physically. I saw them. They started shooting and killing people. They killed my uncle. We ran to the mountain,” he stuttered as he tried to speak further. “I started taking drugs after the attack on my town. I was taking Indian hemps, codeine, tramadol and when I smoked a rubber solution, that was when I lost my peace of mind. I was taken to Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital at Baga road here in Maiduguri and I was discharged after three months in 2017. My drugs finished while I hadn’t recovered yet. I need medication. I still misbehave sometimes.

“A consultant from the International Organisation for Migration used to attend to me here. But he no longer comes. I want to get better and return to school.”

“THEY SAID HOME WAS SAFE”

Even with all these, the government and military keep imploring the IDPs to return to their towns to pick up the pieces of their lives and start life afresh.

“Government told us that our town and homes are now safe and some people went back. But I’m here with my wife and four children. I wish to go back home but it’s not safe,” Usman Bwala told TheCable at the Dalori camp 1. The farmer said his ordeal began when Boko Haram marched into a mosque in Konduga while he was about to break his fast.

Last year at the Nigerian Union of Journalist (NUJ) press week, Usman Zannah, the state commissioner for local government and emirate affairs, lamented that despite the fact that the military had reclaimed some communities, over 350,000 IDPs have refused to go back home.

She appealed to journalist to sensitise the displaced persons to return home and pick up their lives.

At a Nigerian army medical outreach event last year, Tukur Buratai, chief of army staff, also said they had overstayed at the camps despite the liberation of their communities held by insurgents.

In June, at the inauguration of nine gunboats for the task force detachment at Baga, Buratai assured the IDPs that their communities were now safe and secure after the army launched ‘Operation Last Hold’ to “further decimate remnant of the Boko Haram terrorists, ensure return of IDPs to their communities and provide safe and secured environment for the resumption of economic activities in northern Borno.”

THE JOURNEY BACK HOME

With that assurance coupled with the dire living conditions at the camps, thousands journeyed home. The historical return was celebrated. Pages of newspapers were awash with images of IDPs finally going back home.

In April, after an official flag off of Bama IDPs return home by Kashim Shettima, Borno state governor, thousands of the residents were escorted to the town by the military. Babagana Umara Zulum, the state commissioner for reconstruction, rehabilitation and resettlement, reiterated that the state government had made adequate arrangements for the returnees.

Over 25, 000 displaced farmers alone were also said to have returned to Gudumbali in Guzamala local government area of the state, while 10,109 were said to have returned to communities in Kukawa local government area.

BUT HOME IS NOWHERE SAFE YET

Few weeks after the return of some displaced persons to Damboa, six female suicide bombers attacked Abachari village in the local government while about 32 persons lost their lives and several injured. Modu-Zannah Maina, district head of Damboa, told journalists that a lot of those affected were mostly children.

On July 16, insurgents ambushed a military convoy at Boboshe village in Bama and at least 23 soldiers were unaccounted for. On July 21, insurgents, who were said to be going to the Babbangida market to steal food items, ambushed soldiers from 233 special force at Sasawa community in Yobe.

On August 8, suspected members of the Boko Haram sect invaded a military base in Malamfatori area of Abadam local government, Borno, killing 11 soldiers and some civilians. On August 30, Boko Haram fighters in military camouflage attacked a military base in Zari, a small community north of Maiduguri killing about 30 soldiers and while a myriad of other military personnel were wounded. But the army denied the attacks saying the troops repelled the terrorists and kill several of them.

On September 4, some women travelling in a bus were attacked and abducted along Pulka road in Gwoza local government area of Borno state while many people sustained injuries in the attempt to escape.

The 2015 Global Terrorism Index, published by the Institute for Economics and Peace, ranked Boko Haram as the world deadliest terrorist group

IDPs GOING BACK TO CAMPS

With the pockets of attacks on liberated towns and farms, the returnee IDPs cannot fend for themselves, as most still wait for humanitarian aids. Some are still holed up in shelters provided by the government. Lambari said the government has renovated his home in Bama, but he can’t go back yet.

“The governor told us to go back, but he has not finished the renovation process. Many people went back to Bama but the emir, title holders, politicians are not there. Bama is safe, but the bush is not safe. So, it is the same as staying back in the camp.”

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) humanitarian situation update in Nigeria revealed that in July alone, nearly 25,000 new arrivals to camps in Maiduguri were recorded, the highest number 3,953 from Bama – few weeks after the celebrated home. According to the report, the continuous influx of hundreds of newly displaced people in Bama continues to pose challenges in providing sufficient shelters with about 5,000 individuals at the Government Senior Science Secondary School (GSSS) camp currently in need of shelter.

At the El-Miskin camp in Jere, 35-year-old Aishat Usman, said she cannot go back to Monguno with her eight children because those who went back home are coming back to the camps.

Ibrahim Bukar, 40-year-old farmer from Banki Tarmowa, told TheCable at Dalori camp 2 that he would only go back home if he can visit his farms without being killed – although he complained of sleeping space which is not conducive. His friend, 33-year-old Modu Gaji from Ijilije village, interrupted, “Going back could be very dangerous.”

Gwamma, the CAN camp chairman, beamed, “The security situation in Gwoza is uncertain. I left my town since 2014 as a displaced person. They say we don’t want to go home because we are enjoying, but we are not. We want to go back home. We are not happy as IDPs. Boko Haram people are still based in Bayandutse as we speak.”

“WE ARE NOT FORCING THEM BACK HOME”

As the 2019 general election beckon, the return of the IDPs to their communities has raised suspicions that the government is trying to force them home to score political points in the fight against insurgency even when there are no strong indications of adequate security of lives and livelihoods.

In a chat with TheCable, Bashir Garga, National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) north-east coordinator, said the news going round that the government is forcing IDPs to go back to their communities because of the forth-coming elections is not true.

“It is not true that the IDPs are sent home. We are trained persons in humanitarian management. Aside that, we don’t just operate without laid-down guidelines,” Garga said.

“The return of IDPs to their places of ancestral abode or any place they choose is based on an existing document called the Kampala convention. It spells out the way and manner they will be returned. Cardinal among this, they must not be coerced to leave camps to their host communities. In case of returning them, it has to be of their own volition. So, they have freedom of choice to remain in camp or to go to any community of their choice.

Calls made to Texas Chukwu, spokesman of the Nigerian army, were not answered. He also did not reply a text message sent.

AS NIGERIA FACES A CRISIS OF GLOBAL MAGNITUDE

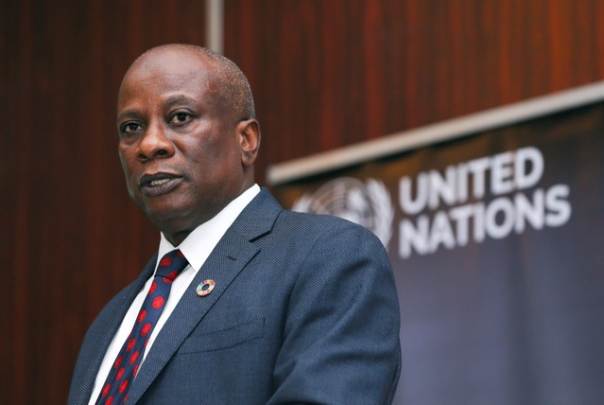

At a conference in New York tagged ‘Strengthening the Humanitarian and Development Partnership in the Lake Chad Region’, the United Nations reiterated that Nigeria is still facing a crisis of global magnitude with 10.2 million people affected in three states in the northeast.

Edward Kallon, UN resident and humanitarian coordinator for Nigeria, said organisation will provide assistance to at least 6.1 million victims of the insurgency by the end of 2018.

Add a comment