Despite ASUU strike, LAUTECH directs students to resume on Thursday | TheCable.ng

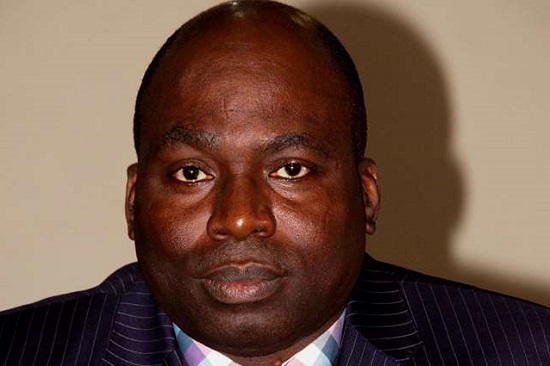

BY JEROME-MARIO UTOMI

Strike actions in the nation’s tertiary institutions of learning is neither new nor unique to a particular university, polytechnic, or college of education, Likewise, the ongoing strike action by the non-teaching staff in the universities under the umbrella of Joint Action Committee(JAC), comprising Non-Academic Staff Union of Educational and Associated Institutions, NASU, and the Senior Staff Association of Nigeria Universities, (SSANU), has only but raised indication to how ‘stressed’ the nation education sector has become.

Expectedly, while blaming incessant strike action on poor funding of the sector, stakeholders advocated that the notion of sustainability in education funding has become increasingly important policy objectives for the government at different levels as well as in the private sector to imbibe. There is also a growing need to strengthen the conceptual understanding of, and need to design effective policies that aim to achieve sustainability objectives, and more importantly, analyze the implications of the proposed policies.

They submitted.

Advertisement

Indeed, these solutions are validly important as it affects the fabric of the sector. However, it has also become overwhelmingly urgent to underline that for a solution to the nation’s education sector challenge to be effective, it will demand being holistic in approach as the rot in the Nigerian education system did not start overnight — but enjoys historical perspective that goes beyond poor funding to include politicisation of the sector, tribalism/nepotism/favoritisms, misguided priorities/policy summersaults among policymakers among others.

Beginning with tribalism/nepotism/favoritism and politicisation of the sector, it has been noted in several publications -which no one has refuted till today – that the federal structure of government agreed for Nigeria in 1954 and reaffirmed in 1960 as an instrument to solve the problems of “forced amalgamation” allowed the federating regions to exclusively control primary and secondary education. In the case of higher education, both the federating regions and federal (central) governments shared concurrent responsibilities.

In the light of the above constitutional agreements, each tier of government in the Nigerian federation was free to establish and control its own Universities.

Advertisement

By 1962, the federal government controlled only two universities namely the University of Ibadan established by the British colonial government as a University College in 1948 but became a full University in 1962 and the University of Lagos established by the post-independence federal government in 1962.

The staffing (academic and administrative) of the two federal universities was dominated by personnel from western and eastern Nigeria origin and a contingent of foreign expatriate staff. There were then very few personnel in academic and administrative positions in these universities from northern Nigeria to mount any competition.

In each of the federating regions, there was a regional government university as of 1965 namely: University of Nigeria, Nsukka (UNN) founded and established by the eastern Nigeria government in 1960. The University of Ife, Ile-ife (UNIFE) was founded and established by the Western Nigeria Government in 1962, and Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), Zaria, founded and established by the Northern Nigeria Government in 1962. The mid-western Nigeria created in 1963 could not understandably establish any university before the political crisis of 1967.

All the above universities both federal and regional however tried to excel and to maintain the highest standards of excellence and consequently employed Nigerians on merit with no consideration whatsoever as to their ethnic nationality and or region of origin. This situation allowed high-level standards to be sustained by all the universities in Nigeria.

Advertisement

The federal universities in 1963 – 1965 began to experience academic and administrative leadership problems similar to the political power struggle among Nigeria’s political power blocks.

At political independence in 1960, the federal government advised that a suitable Nigerian be selected and appointed the vice-chancellor of the premier University of Ibadan as a mark of Nigeria’s independence.

Professor Kenneth Onwuka Dike, a distinguished historian, scholar and world-class academic, was appropriately appointed the first Nigerian vice-chancellor of the University of Ibadan. Professor Dike happened to be Igbo from eastern Nigeria and to balance the situation a distinguished administrator Mr. N. A. Ademolekun, a Yoruba, was appointed the first indigenous registrar of the University of Ibadan to the delight and satisfaction of everyone.

It was reported that things went sour among the Igbo and Yoruba academics when three further administrative positions were made in respect of the headships of the mathematics and history departments respectively and that of academic registrar, all the three being Igbos. This did not go well with the Yoruba academics and generated silent dissension between them and the Igbos. The situation of distrust among the Igbo and Yoruba academics was such that a non-Nigerian (in fact a university librarian from New Zealand) had to be appointed in place of any Nigerian academic to act as vice-chancellor when Professor Dike was away on leave of absence.

Advertisement

In 1962, Professor Eni Njoku, a distinguished academic, scientist and administrator, was on merit appointed the first vice-chancellor of the second federal university namely the University of Lagos. Professor Njoku, an Igbo, appointed was to be reaffirmed after three years in 1965.

In 1965, Professor Eni Njoku was reported to have performed excellently well from 1962-1965 that the senate of the University of Lagos unanimously recommended that Professor Njoku be reappointed until retirement age. This meant that the two federal universities were to continue to be headed by Igbos.

Advertisement

The governing provisional council of the University of Lagos, with seven Yoruba members out of ten and the federal minister of education to which the council reported also being Yoruba nationality, ignored the unanimous recommendation of the university senate and went ahead and appointed a Yoruba academic who was not a candidate nor reported upon in accordance with university tradition by the senate.

The refusal of the university council to reappoint Professor Njoku threw the University of Lagos into a major crisis. Some of the details were widely published by Nigeria media and Ridgeway Printers of Lagos on March 19, 1965 and May 5, 1965.

Advertisement

The action of the university council threatened inter-ethnic and international cooperation in the University of Lagos resulting in the exodus and return of academic staff of eastern Nigeria origin (mostly Igbos) to eastern Nigeria to be absorbed subsequently by the University of Nigeria, Nsukka in late 1965.

Similarly, a number of distinguished foreign academics withdrew from the University of Lagos and returned to their various countries. Professor Njoku himself was subsequently appointed the vice-chancellor of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

Advertisement

And there it is.

This new awareness more than anything partly explains why the appointment of vice-chancellors, provosts and other principal officers in the nation’s education sector is today stripped of merit and centre more on tribal/ethnic and other political considerations.

On the Nigerian government and ASUU’s rancor, reports abound signifying that both parties are in a face-off over lack of funding for a long time. In fact, the ASUU strikes date back to 1988 when the union’s officials started a protest over wage increases. This led to the suspension of the union and then reinstated in 1990. Following another strike in 1992, the ASUU was, again, hammered by the military government and restored yet again, after an agreement was reached with the government.

In the mid-1990s, two more strikes hindered university education in Nigeria once more. Fast forwarded to 2003, when the union again, went on strike over the manner the government handled education. There was a three-month strike in 2007 on mistrust when the union’s demands were not met.

In May 2008, it was reported, the ASUU went on strike for a week in order to send a message to the authorities that they deserved higher salaries and wanted the return of lecturers who had been sacked. In June 2009, there was another spat with the federal government on terms agreed to in 2007, which led to a three-month strike. It was the strike that gave birth to the MOU, which was eventually signed with the government in 2012. The MOU notwithstanding, strike actions in the nation’s tertiary institution have continued unabated.

So in the objective estimation of this piece, the ongoing NASU/SSANU strike which shares common features with a recent one that lasted for close to one year, by the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU), to kick against government directive on the Integrated Payroll Personnel Information System (IPPIS), press for the revitalisation of universities; renegotiate 2009 agreement and push for the Earned Academic Allowances (EAA) of members, is but the second half of the circle.

To be continued.

Utomi is the programme coordinator (Media and Public Policy), Social and Economic Justice Advocacy (SEJA), Lagos. He can be reached via; [email protected].

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment