Primary Health Center, Unguwan Nupawa, Nasarawa State

BY KAFILAT TAIWO

Sefiya Abdul-Rasaq, 52, and her co-wife, Aisha Abdul-Rasaq, 46, reside in the Doma LGA of Nasarawa state. They cannot visit the hospital without their husband, Mallam Idris Abdul-Rasaq, not even during childbirth.

‘‘My husband doesn’t allow us to visit the hospital for treatment except if he is around. He ensures he oversees the treatment process. Also, he doesn’t allow the opposite gender to touch his wives and children,” Sefiya said.

‘‘This was because of what happened when I lost my only son in 2002. Then, I was in labour, and the only person on duty went to buy fuel, Before he got back, I was weak, and he tried to help, but I later lost my son on the third day. This incident led to my husband marrying Aisha.

Advertisement

‘‘When he married her in 2005, he warned me never to allow her to visit hospitals except if he gave directives. Even the children don’t go to the clinic without their father’s consent.”

Their story is similar to that of Nana Awwal, 38, who claimed her husband Muhammed Isa stopped her from visiting the hospital because the four staff members at the local primary healthcare centre (PHC) were two male health workers, a female nurse, and an attendant.

She said she was emotionally abused by her husband several times whenever she visited the hospital during pregnancy, forcing her to deliver her baby at home without medical help.

Advertisement

‘‘My husband will always ask whether it was a male that examined me or a female. Once I tell him it’s a male, he hurls different abusive words at me. Sometimes, we got involved in heated arguments that made him beat me,” Awwal said.

“After the birth of our third child, I went to report his constant beatings, which made him stop. We agreed that a male wouldn’t attend to me whenever I visit. My new baby was delivered at home.”

Awwal was one of the survivors of gender-based violence who reported her encounter with her husband in 2020.

GENDER DISCRIMINATION IN HEALTH SECTOR

Advertisement

Gender bias refers to actions or thoughts based on perception or preference for one gender over another.

An investigation revealed the prevalence of this bias in the Nasarawa state healthcare system, and how it has hindered the delivery of quality healthcare services in the state.

Research shows that the bias often complicates health issues and promotes gender-based violence (GBV) in families and homes.

Advertisement

DATAPHYTE’s investigations show that some of the factors influencing the bias are religious beliefs, traditions, trauma and inadequate knowledge of the importance of gender equity in the Nigerian healthcare sector.

For instance, Abdulrasaq AbdulGaniu stopped his wives from visiting the hospital after he lost his first male child. According to him, he often narrates his experience to people so they can learn from it.

Advertisement

‘‘My religion doesn’t allow a male and female to touch themselves; there has to be respect when dealing with the other gender. I don’t want a male health worker to touch my wife. It is unacceptable. The first time a male health worker touched my wife, we lost the baby, our first male child,” he said.

“After the incident, I was ready to fight them, but the community elders begged me. Even a female person can’t attend to me as a man.’’

Advertisement

When Shehu Kabir took his wife, Hajara, to the Doma Primary Healthcare Centre for an antenatal appointment, he released the attendance card to her only after she confirmed from peeping through the palpating room that some female student health workers were in the room assisting the male health workers on duty.

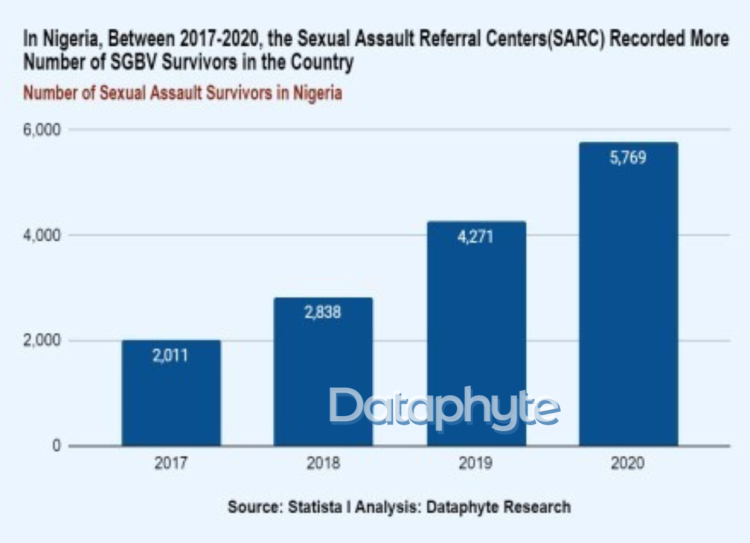

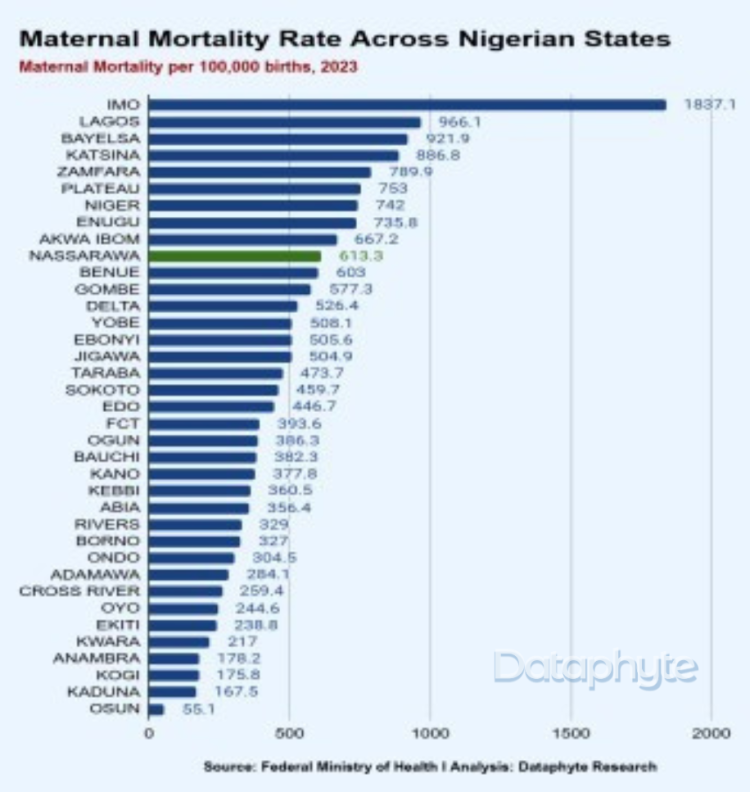

Data shows that Nasarawa state has the 10th highest maternal mortality rate among the 36 Nigerian states, including the FCT. The World Health Organisation (WHO) stresses the importance of ante-natal visits for pregnant women. Yet, Kabir allowed Hajara to access the facility only after being assured that there were female health workers at the clinic to attend to her.

Advertisement

PREFERENCE AMID SHORTAGE

There was a shortage of the various cadres of healthcare workers at several health facilities in the state visited by this reporter for this investigation.

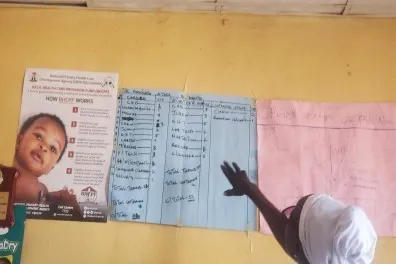

According to the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA, an ideal primary health care centre (PHC) centre should have a minimum of 24 staff members. These include one medical officer, one community health officer (CHO), four nurses or midwives, three community health extension workers (CHEWs), one pharmacy technician, six junior community health extension workers (JCHEWs), one environmental officer, one laboratory technician, and one medical records officer.

As support staff, a PHC should also have two health attendants, two security guards, and a general maintenance staff.

Apart from personnel, NPHCDA also recommends that PHCs have a well-open ward, labour room, children’s and female wards, doctor’s office and staff quarters, an ambulance for referral drugs, and equipment for immunisation, preventive, and basic curative care.

During the visit, four male and nine female health workers and other staff members from various departments were present at the Doma Primary Health Centre.

Ismaila Kazeem, a principal nursing officer (PNO), said female patients and their relatives always refuse to be attended to by male health workers.

Two female and three male health workers were present at PHC Tundun Abu, which is in the Lafia LGA.

‘‘We run a shift here. Sometimes, we have male and female health workers on duty, but the genders sometimes pair together,’’ a staff member said.

At the Unguwan Nupawa PHC, there were just three health workers, including two females, and the support staff.

At PHC Angwaje, many employees were either contract staff or volunteer community and health extension workers (CHEWs) who earn between N3,000 and N10,000 monthly hoping to get absorbed into the healthcare system.

The officer in charge, Aperuwa Bako, said men often demanded that their labouring wives be cared for exclusively by women.

‘‘At the facility, we are short-staffed and often rely on volunteers to manage the workload. In one emergency, a man insisted that I shouldn’t touch him until others convinced him to cooperate, given the severity of his accident,’’ Bako said.

‘‘I have witnessed countless times when a patient asks if there is a nurse on duty because they know we don’t have a doctor here, even during cases of emergency. The reality remains that we are short of staff, and being selective can’t solve the problem.’’

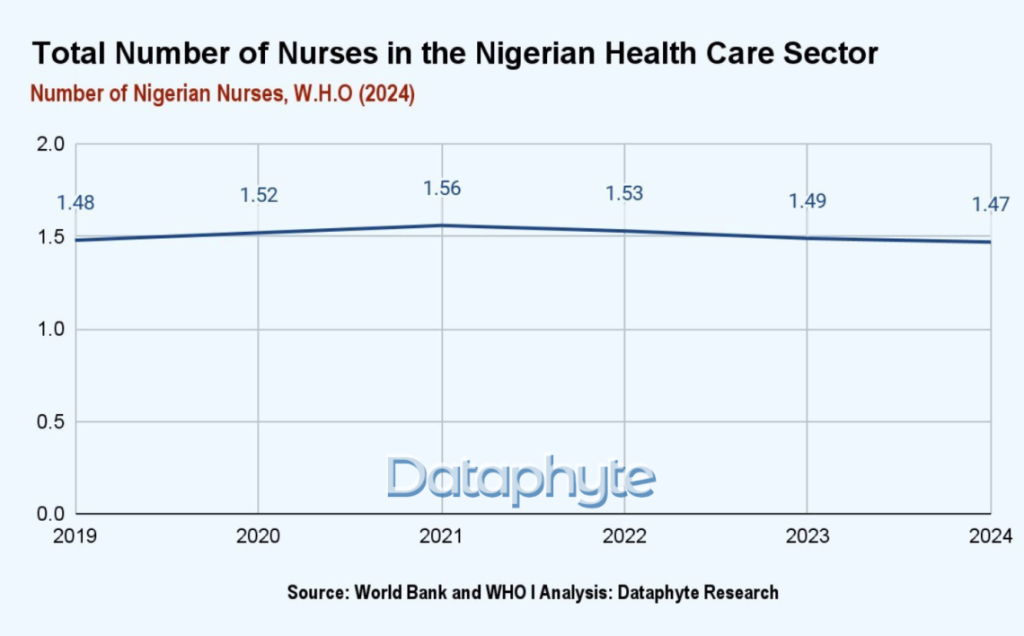

Meanwhile, WHO data revealed that there is a decline in the number of nurses in the Nigerian healthcare system. This decrease will likely lead to errors, higher morbidity, and mortality rates in the country.

Meanwhile, a Royal College of Nursing report says, ”Inadequate pay, insufficient staffing to ensure patient safety, harassment and discrimination in the workplace, a lack of career progression and unsafe working conditions’’ are factors influencing the shortage of nurses in the health care system.

INSUFFICIENT FUNDING A MAJOR BARRIER

WHO advised that budget allocation, execution rules and practices are crucial to supporting progress towards achieving success in the sector. Specifically, how the budget is presented and organised determines how resources flow and reflects sector priorities.

Over the years, the annual budget of the Nasarawa State Ministry of Health has continued to increase. In 2020, N198.7 billion was allocated to the ministry and N1.2 billion in 2021. The amount dropped to N1.1 billion in 2022 but increased in 2023 and 2024.

The budget outlook shows that from 2021, Primary Health Care received N1 billion, the amount reduced to N686. 1 million in 2022, it increased to N725.8 million in 2023 and dropped to 35.7 million in 2024.

FINDING BALANCE BETWEEN PROFESSIONALISM AND REALITY

While there have been strides towards ensuring that women have greater access to healthcare services, the conversation about equality goes deeper than this. It touches all aspects of the health sector, notably leadership, education, and empowerment.

Gender bias is one of the challenges facing healthcare workers in the Nasarawa state at the primary and tertiary levels.

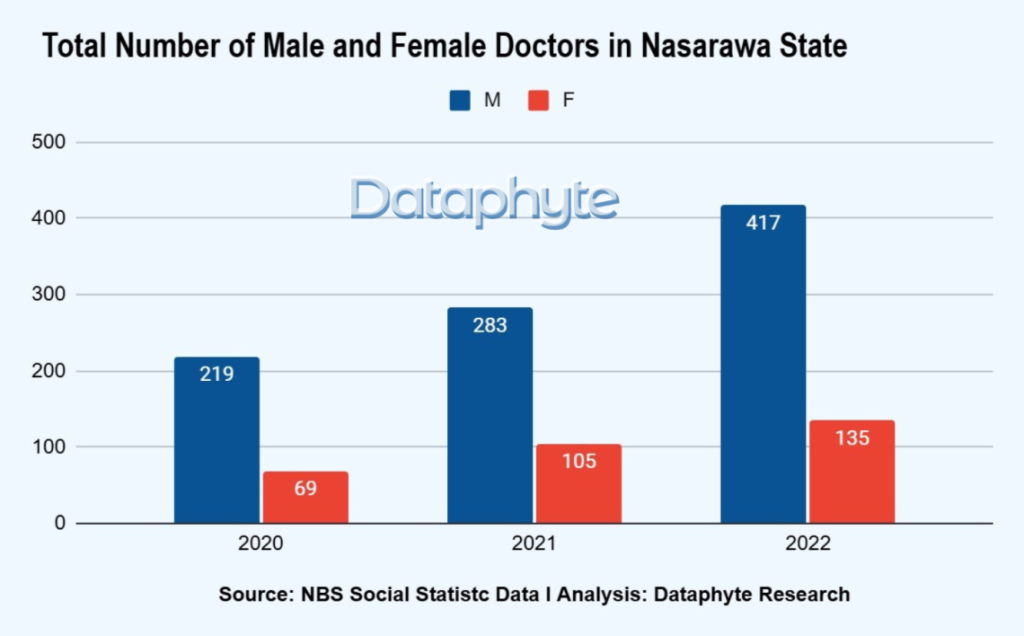

Emmanuel Agbade, a consultant gynaecologist, said there are more male doctors in the state than females, especially in obstetrics and gynaecology. Although they often face biases, chaperones have been helpful.

‘‘The bias is always there, but the chaperones often serve as an intermediary between the patients and us depending on their genders,’’ Agbade said.

Ibrahim Awwal, a perioperative nurse at the Federal Medical Centre Lafia, explained the challenge of being a male nurse.

‘‘Despite the brain drain in the system, many male health workers struggle to discharge their duties due to the discrimination,’’ Awwal said.

Nurse Ene at the Federal Medical Centre, Lafia, said there were several recorded cases of health workers’ preference.

‘‘We nurses mostly act as chaperons, to serve as an intermediary between the doctor and the patients even when the spouse or patient relatives allow a male gynaecologist to perform his duty,’’ Ene said.

Abraham Odey, a male community health extension worker (CHEW) at Kofar Fada PHC, narrated how the disparity is reducing quality health care delivery

‘‘This has been the norm within the facility where patients dictate to their wives what to do, who to relate with and whose service is the best for them. Most men do not want their wives to be attended to by male nurses. I was on duty last month when a woman was in labour, and the man insisted that I shouldn’t lift her legs while trying to enter the cab,” Odey said.

‘‘These situations often frustrate our work where we put no or little effort when we come across people like them.”

“Most men are uncomfortable with us treating their wives,” said another nurse, Danfari. “We can’t even check their BP; this is why a hundred per cent of our staff at the maternity and family planning sections are female.”

EXPERT VIEW

Esther Etim, a public health expert and gender advocate, said understaffing and underfunding contribute to the challenges within the health sector.

For the general public, factors such as culture, religious beliefs, and upbringing play significant roles in influencing gender bias within the sector.

“The gender preference among patients is happening. There are not many female doctors, and still, patients will discriminate on who to care for them. If their preferences are not met, they will rather go home or visit a TBA centre where their health issues get complicated,’’ Etim said.

Nnenna Onwere, a medical practitioner, said obstetrics and gynaecology is a male-dominated specialised field. Although she acknowledged that more females are joining, their number has yet to match that of the males.

She said cultural and religious beliefs in the society are behind the gender bias.

‘‘The bias is mostly among the northern people, especially the elderly. A male patient would rather have a male doctor or health worker care for them. Also, when it comes to childbearing, women do not have issues; their preference is majorly influenced by their spouses, who prefer to see a female health worker attend to their wives,” Onwere said.

‘‘In some cases where there are no female doctors available, other health workers serve as chaperones to avoid any form of allegations or temptation from either the doctor or the patients. The chaperone idea is no longer effective due to understaffing in the health sector, but sometimes, patients trust their healthcare provider.’’

However, Mutiu Popoola, a gynaecologist, advised that ‘‘one of the ways to solve the problems is for the government to employ more people to the system to build trust and ease the burden on health workers.’’

‘THE STATE’S HEALTH MINISTRY IS UNAWARE’

John Damina, permanent secretary of the Nasarawa State Ministry of Health, said the ministry had not recorded any case of gender bias impeding the delivery of quality healthcare.

However, Damina said healthcare facilities do not have quarterly reporting mechanisms, which could illuminate any underlying issues involving patient experiences and perceptions.

“To ensure quality health service is maintained, officials from the ministry regularly conduct on-site visits to various hospitals, where they engage with patients to gather feedback on their experiences and satisfaction with the services provided,” he said.

‘‘The ministry has not heard about gender bias affecting the healthcare system. We do not have quarterly reports from our health facilities, and we visit these hospitals to hear how patients feel about our services; none of them ever mention them to us. Even while I was practising as a Doctor at Dalhatu Hospital, Lafia, between 2000-2010, I had never come across such an incident before.’’

The story was supported with funding from the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID).