This report was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

Ibrahim Maryam, 4, was skipping around her home in Dutse Mpape in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital, her tiny feet barely touching the dusty floor in the compound, when the earth beneath her began to shudder. The sound of explosives crackled through the air like a fierce storm, sending tremors through the walls and rattling the windows.

As the Chinese company blasted rocks in the nearby quarry without warning, Maryam’s eyes grew wide with fear, her smile frozen in rude shock. From that moment on, Aliyu Ibrahim, Maryam’s father, knew he had to shield her from the terror that lingered long after the dust settled. He wrapped Maryam snugly to his chest. The blasts echoed through their lives, a constant reminder of the fragility of their world.

Ibrahim had been living in the local community — 16.6km away from the city centre — for 12 years before Perfect Stone Quarries Limited started operating in the area six years ago.

The father of three said Maryam and her two brothers are now used to the trembling sound of the rock blast in the area. He has also mastered the art of holding the kids close to his body to comfort them during the blasts.

Advertisement

During a visit to Ibrahim’s house in March, he walked through the cracked parts of the building branded with cemented patches to save it from caving in. He said the company would rarely engage in its blasting operations without the fly-rocks hurtling their roofing sheets or structures.

Flyrock, or wild flyrock, is a rock that is ejected from the blast site in a (controlled) explosion in mining operations. The term refers in particular to rock that flies beyond the blast site, causing injuries to people and property damage.

“We are scared of something more terrible happening to us, so we took our cries to them. We complained about not enjoying the impact of the work being done around us, especially because our kids are always panicking; also they are destroying our property and making us use our money to fix it every time,” Ibrahim said in Hausa.

Advertisement

“They came to meet us here. We were on this land before their arrival. I personally (with my family) have been living here long before they came to build their company on the land.”

Ibrahim’s story is one of many in Abuja communities suffering from health risks associated with living close to a quarrying site.

EXPLOSIVE BLASTING OPERATIONS CAUSING HARM, DISRUPTION

Israel Rita lives two apartments away from Ibrahim’s house with her three kids. The divorced mother of two detailed her harrowing experience as a resident of the community.

Advertisement

The 27-year-old woman noticed she had a rapid and irregular heartbeat due to the frequent, unexpected explosive sound from the blasting site. A nurse from the nearby primary healthcare centre ran a check on Rita’s pulse and noticed an abnormally high reading.

Rita has experienced the worst of the situation.

In November 2023, she was preparing lunch for her family when the company’s siren pierced the air, signalling the start of their day’s blasting operation.

Abandoning her meal preparations, she gathered her children and they trekked out of their compound to seek safety and refuge from any potential accidents.

Advertisement

After 50 minutes of waiting for the blasting to begin, she returned home to take a nap, but the peace was short-lived.

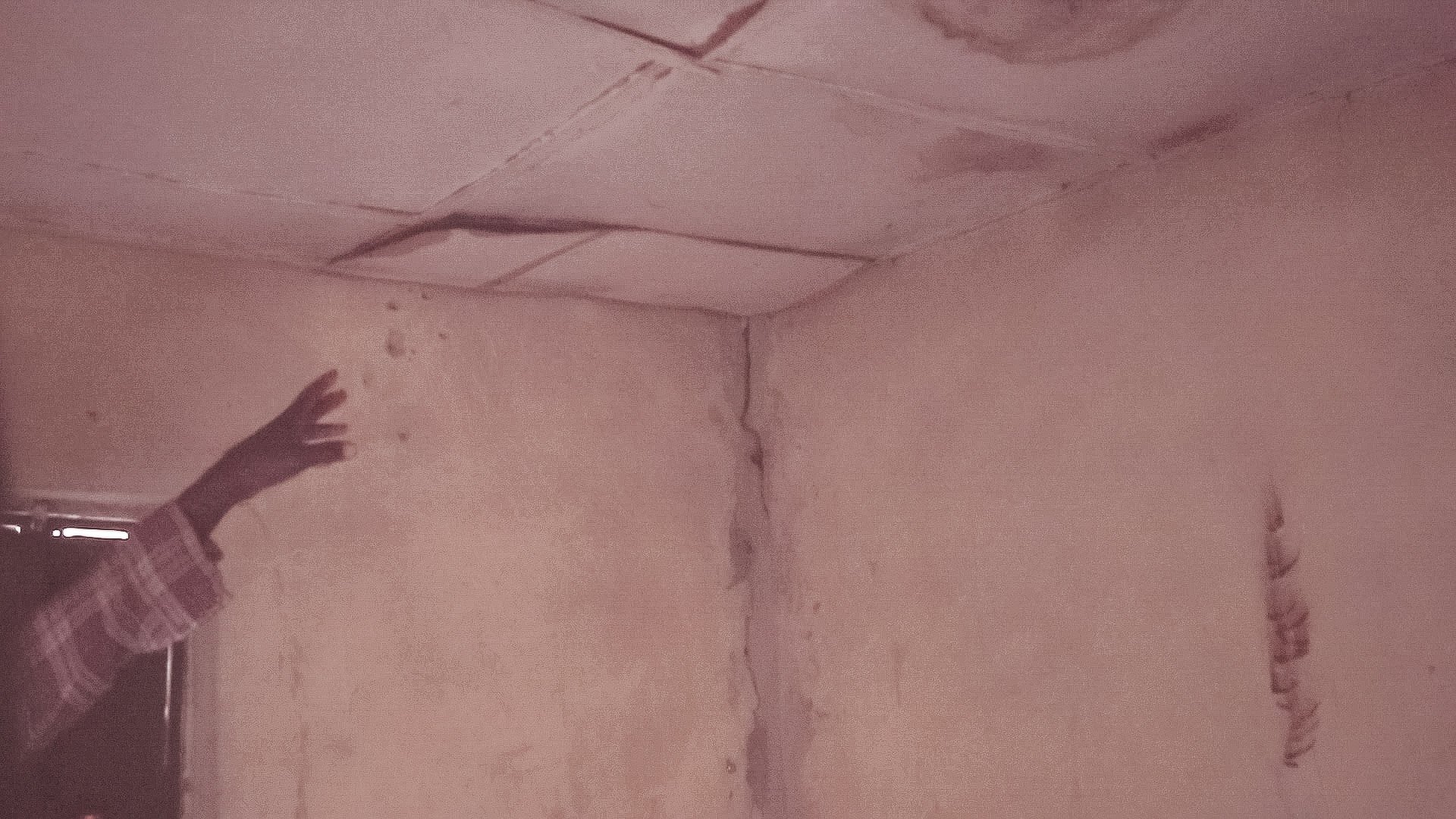

The violent vibrations and heavy blasting sounds shattered the tranquility around her, jolting Rita awake. The force of the explosion dislodged the ceiling boards and cracked a significant portion of her wall. Rita said some residents were reportedly injured after the dust of the blast settled.

Advertisement

“Whenever they want to blast, even if it’s happening under the rain, we are all expected to leave our houses because of flyrock or casualty induced by the heavy vibration. During the week, they blasted again. The wall here (pointing to the right wall) cracked badly and it may soon fall. The ceilings fell on me too. We later realised that a man was injured while the window glasses in his house were all shattered. God is our only saviour in this community,” Rita said.

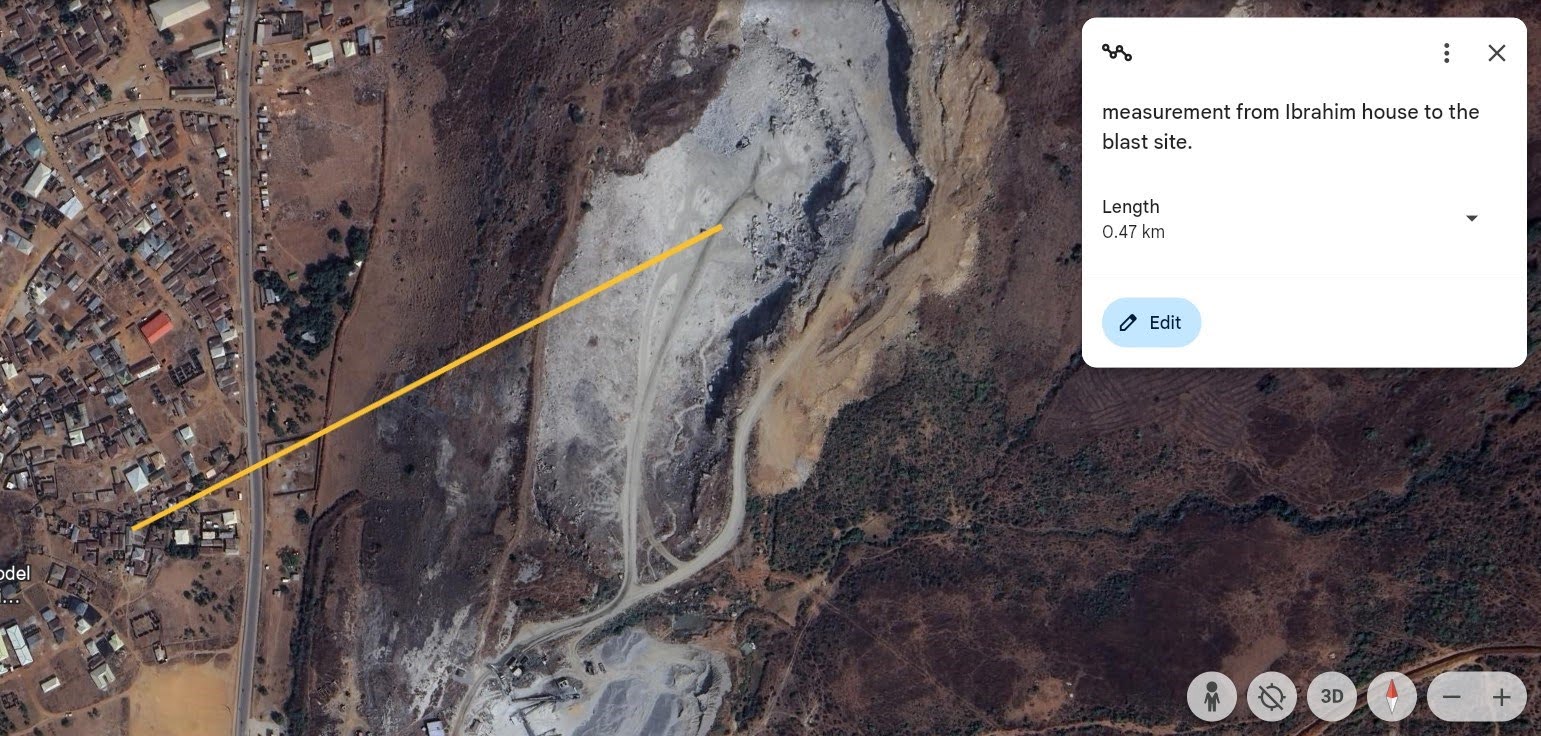

These reporters took the coordinates of Ibrahim and Rita’s neighbourhood and plotted them back to the blasting site. Using Google Earth, an open-source app with satellite imagery, it was discovered that the distance was just a meagre 0.47km.

Advertisement

However, the National Environmental (quarrying and blasting operations) Regulations, 2013, states that “a person shall not locate a quarry or engage in blasting within three kilometres (3km) of any existing residential, commercial or industrial area”.

Peter Yawe, a medical officer, said the proximity of Indigenous communities to rock blasting sites plays a crucial role in determining the extent of their exposure to pollutants and the associated health effects.

Advertisement

“Communities situated closer to these sites are likely to experience higher concentrations of airborne pollutants, increasing their risk of short-term health effects such as respiratory tract irritation and eye discomfort. Long-term exposure to high levels of air pollutants can contribute to the development of chronic health conditions, including respiratory diseases and cardiovascular disorders,” he said.

The residents narrated more than a dozen stories to us, all reeking of frustration and sadness based on their daily experiences in the community. While many complained of dusty breath, some said their aged parents were scared of developing ear defects due to the frequent loud noise.

“We have many people with high blood pressure. They keep complaining but no one is listening to them. This thing is affecting people so much. The leg of a man was broken when it was hit by a flying stone. But he was taken to the hospital and treated,” Shadrach Unana, Rita’s next-door neighbour, narrated his ordeal since he moved to the community eleven years ago.

During a visit to the company’s facility in March, these reporters were denied access. We were also requested to leave our phone numbers and photocopies of our ID cards, which we did. But they did not call back.

Karikati Stephen, Perfect Stone Quarries manager, confirmed in an interview that flyrocks have become a regular feature of the blasting operations in the community, but measures are in place to curtail the effect.

“Of course, it does happen, but measures are in place to forestall it because wherever we have a quarry site, there is always encroachment for mining generally. For that reason, flyrocks affect those that have encroached into the company’s property,” Stephen said.

“Now, the company has taken a step to further ask for the extension of the rock to be far away from residential areas and that will solve the problem of flyrock affecting settlers.”

THE SAME PROBLEM IN KUBWA

Olorunfemi Kehinde, an architect, lives in Kubwa Extension II Relocation Residential Area, a community near the British-owned Zeberced Quarry Limited.

He has taken an unconventional approach to demonstrate the intensity of the vibrations caused by the quarry’s daily blasting operations. He now places a cup of water on his table, using it as a makeshift seismograph to gauge the violent shaking that rattles his home.

The tremors generated by the blasts are so powerful that, depending on their intensity, they can cause the water in the cup to oscillate violently or even spill over the rim.

During one of Zeberced’s blasting operations in 2022, Kehinde’s makeshift gauge captured the intensity of the vibrations and the aftermath resulted in the collapse of his apartment’s left-wing fence.

Kehinde said the story would have been different if the kids were outside playing. The collapsed fence, which served eight families, required collective efforts from tenants and the landlord to repair as attempts to reach out to Zeberced for assistance failed.

“There was no positive response from the company (Zeberced). We’re just helpless. Nobody to talk to. Everybody has just taken it like that,” Kehinde said.

A building under construction next to his apartment would later cave in during another heavy blast a week later.

Zeberced started the production of crushed stones in the area during the first quarters of 2009 by processing the granite mine, covering an area of 3,168,344.m². Ever since then, its activities have been pervasive, enveloping the entire area with constant blasting of rocks, incessant stone milling, and noisy heavy machinery. The incessant milling sound is a shrill reminder of the quarry’s presence; for newcomers, it can be a tormenting experience.

Trucks transporting granite and sand from the quarry to other areas are a common sight, adding to the daily disturbances caused by the company’s operations. The company describes the facility as the “most efficient and biggest quarry of its kind in West Africa”.

Nigeria earned a total sum of N193.59 billion from the solid minerals sector in 2021. The figure shows an increase of ₦60.32 billion or 51.89% growth when compared to the 2020 revenue flow of ₦116.82 billion. From 2007 to 2021, the total revenue accrued from solid minerals to the government was N818.04 billion. On production, the total volume of solid minerals used or sold in 2021 was 76.28 million tons, with a royalty payment of N3.57 billion.

In 2021, the minerals with the largest production volume were granite, limestone, laterite, clay and sand. Dangote Plc accounted for the highest production with a total of 28.8 million tons. BUA and Lafarge accounted for 8.4 and 4.3 million tons, while Zeberced accounted for 3.3 million tons, respectively.

Earlier, before the 2022 incident, Kehinde’s toddler would wake up from his sleep and start crying whenever there was a blast. The one-year-old boy would not stop crying for longer hours until the doctor examined him and found out that he was triggered by shock.

Aside from the heavy vibration, the community suffers from dust particles emerging from the blasting site. Residents told these reporters that they breathe in heavy dust and suffer lung function diseases and chest tightness.

“We can wash our cars in the morning and in two hours, you will notice the car is full of white particles. The same white particles are always seen on our clothes when spread for drying in the compound,” a resident who sought anonymity said.

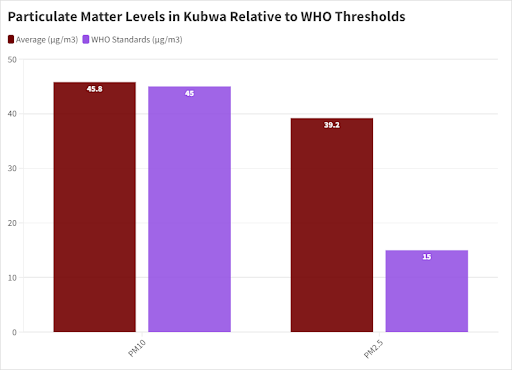

Using Code for Africa’s air sensor device, we measured particulate matter (PM) 1, 10, and 2.5 around the community for 3 months — January, February and March 2024. While PM2.5 is particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 micrometres (ug/m3) or less and can be inhaled deeply into the lungs, making it harmful to human health, PM10 is just of the same model with a diameter of 10 micrometres (ug/m3) or less but less harmful compared to PM2.5 and it does not penetrate the lungs. PM1 is an extremely fine particulate with a diameter of fewer than 1 microns and it can cause damage to the heart, lungs, and other organs in the body.

In the community, the device measured an average PM10 concentration of 45.8 μg/m³ compared to the World Health Organization (WHO) standard of 45 µg/m³. For PM2.5, it captured an average value of 39.2 μg/m³ as again the WHO’s 15 µg/m³.

Commenting on the data, Rose Alani, the lead of the Air Quality Monitoring Research Group (AQMRG) at the University of Lagos, said the community is at great risk of poor air quality due to the high concentration of dust particles.

Alani said the residents may suffer from the release of harmful pollutants like carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter.

On two different occasions, in March and April, these reporters were denied access to the Zeberced facility. Mahmut Bulduk, the company’s spokesperson, said he was not permitted to speak on the matter and directed us to reach out to the ministry of mines.

According to the Solid Minerals Development Fund (SMDF), Nigeria’s mining sector boasts 44 different types of commercially viable minerals worth an estimated $700 billion, but limited capital injections, inadequate geo-mapping tools, and widespread illegal mining have left Nigeria struggling to capitalise on its reserves.

POLICY PARALYSIS: KARSHI COMMUNITY BATTLES BLASTING NIGHTMARES

In Nigeria, it seems there is a war between formulating a policy and implementing it. It is also to the disadvantage of the citizens when laws are only implemented in the books without real guidance. This is the case in Karshi, an agrarian community sitting on the boundary between Nigeria’s capital and its neighbouring Nasarawa state.

The blasting activities of Kaidi Investment Limited have made the lives of residents at Karshi Army Estate, Nasarawa state, hell on earth. The estate is one of the projects of the Nigeria Army’s Post-Service Housing Development Limited (PHDL) built to provide affordable houses and land for personnel and civilians when they retire.

However, residents said the resulting side effects from the blasting site less than a kilometre away have not allowed them to retire in peace.

Benedict Loveday, the vice chairman of the estate with over 80 houses, told these reporters that whenever Kaidi wanted to commence their blasting activities, there was usually a 15-20 minute alarm system to notify residents to leave their homes to avoid any form of casualty.

However, residents said since June 2023, they have only heard explosive sounds from the quarry. There was no alarm for residents to take cover before the blast. Loveday said during a meeting with the quarry’s management staff, they were told the alarm was faulty. The alarm system was not repaired as of March 2024, when these reporters visited the estate, and residents now pay dearly for living close to a blasting site.

“So, just like that, while we’re just relaxing with our family members in the house, the blast would just take us unaware. The last one was like four major blasts in a single day. Whenever this blast happens, the whole environment is clouded with thick dust. We know it’s very harmful to our health, but there’s nothing we can do about it. This is our home; this is where we live,” he said.

On one of the weekends in October 2023, the households in the estate were resting after the hustle and bustle of the week. Without notice, they heard a disruptive explosion. They knew it was from the Kaidi blasting site. These reporters were shown the indelible scars of the blasting: from cracks on the majority of the building to broken windows, while interior fittings fell off in other houses. Residents said two of them are suffering from “shock-induced sicknesses”.

“Mr Charles’ wife (one of the residents) has been suffering from high blood pressure. It affected her after the blast. Yes. We had a lot of POP ceiling cracks. We had a lot of chandeliers that fell, broken glass windows, and cracks in walls. So, the blast has gone on to affect both our health conditions and the house we live in,” Loveday said.

While describing the intensity of the blast, Daniel Owen, Loveday’s 5th-door neighbour, said: “The last two blasts would be the first of their kind that we’ve ever witnessed. My child was shocked. He was actually sleeping. He woke up from sleep. My mother-in-law ran to me in the kitchen, where I was doing the dishes. She came to me and said, what’s happening here? I told her it was a blast. She said, no, she couldn’t stand it.”

Another resident, Peter Ogbange, said whenever rock blasting is carried out at the quarry, he ties a wrapper to his kids’ noses and blocks them. He does this to prevent them from breathing in the heavy dust covering the area.

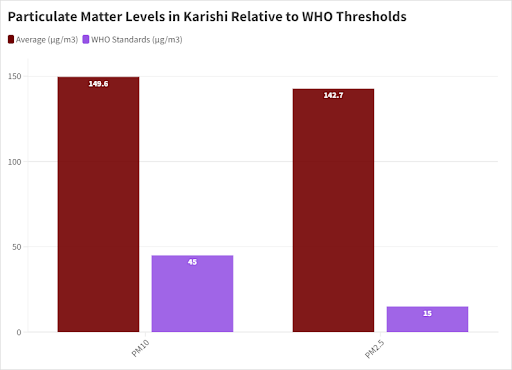

Among all the communities where the air quality data was captured, Karshi’s was the worst. Within the three months of continuous observation, the devices measured an average PM10 concentration of 149.6 μg/m³ and PM2.5 concentration measures at 142.7 μg/m³ — both significantly against the WHO’s standard of 45 µg/m³ and 15 µg/m³ respectively.

Transmitted data from the sensor also showed that the PM10 levels exhibit variability across different dates in the area. On January 15, the average PM10 level was 182.8 μg/m³, while on February 25, it dropped to 36.9 μg/m³. Extremely high PM10 levels were recorded in the data on March 15, as it spiked to 800.16 μg/m³, and on March 26th, it surged to 1944.01 μg/m³. These dates were confirmed to be the time when the quarry company was carrying out blasting operations.

We wrote to the Nigerian Army housing scheme to get their comment on why approval for a quarrying site was given a few feet away from a residential housing project. The army did not respond to the letter.

However, Salifou Hammani, Kaidi Investment Limited manager, said the company has reduced its rock blasting operations to three times a week due to the recent complaint lodged by community residents to the mines ministry in Lafia, Nasarawa state capital.

“They asked us to reduce the rock blasting to two times a month, which we have been doing. We have not heard their complaints again. The Ministry of Mines investigated and told us how to blast so that it wouldn’t affect them, but we have been giving them water supply,” Hammani said.

PROFIT OVER PEOPLE’S HEALTH

Barnabas David, a union member of quarry marketers in Abuja, said most quarry companies are more concerned about profit than mitigating the impact of their activities on the people.

He said the union has been advocating that the quarry companies carry out community development projects that will benefit the people.

“Most quarries in Abuja are just business-centric. They’re just focused on making money. Their business is to just make their money and then leave. If there’s anything they’re going to do, they pay it to the village head, and of course, the village head would use the money to develop his or her community,” he said.

Barnabas further lamented about the dilapidated roads leading to major quarries in Abuja.

MINISTRY’S REACTION

Segun Tomori, media aide to Dele Alake, solid minerals development minister, said in an interview with TheCable that before quarry companies get a license, after obtaining the host community’s consent, certain environmental obligations are expected before the commencement of operations.

He said miners have to obtain an environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) which involves conducting baseline studies of the environment of the virgin land, ecological studies, water and soil sample evaluation, and assessment of the vegetation, amongst others.

In reaction to measures put in place to curtail the effect of blasting on people close to the quarrying site, Tomori said there is a permissible distance to the populace that a quarrying site must have. He claimed what is happening in some cases, like in the FCT, is that development has brought people close to sites that were initially far from settlements.

He said Mines Environmental Compliance’s (MEC) duty is to ensure that operators comply with environmental standards. He said MEC investigates cases of breaches during periodic inspections and through information sourced from members of the public.

Reacting to how communities deal with severe health impacts, he said the ministry advises the companies to always wet the ground. He said that in cases where people get ill as a result of the activities, the companies are mandated by MEC to offset the treatment of those affected and put in place better preventive measures.

“Ultimately, in FCT, for instance, collaboration is needed with FCTA, Ministries of Solid Minerals Development and Environment to ensure that settlements are kept far away from quarrying sites or within the tolerable distance as permitted by environmental laws. This collaboration will also suffice across the country to address the challenges of the probable impact of mining activities on the environment,” he added.

BY SAMAD UTHMAN AND AJALA SAMUEL

Add a comment