BY CHIGOZIE VICTOR

A school in rural Nasarawa struggles on with only two full-time teachers. And on the day HumAngle visited, it turned out one of those teachers had been called away by the education board for a meeting.

One thing so unavoidably distinct about the head teacher’s office is the plastic furniture stacked against the walls of the room.

The pattern of the arrangement is such that the furniture is placed around the edges so that there is at least some space for the headteacher to use.

Advertisement

On a second look, you would notice that there are no books or teaching materials anywhere in the room. The place looks nothing like a head teacher’s office. It looks more like a storeroom for chairs.

Mr Abdullahi’s office is in the old block of classrooms a few feet across the new one they had just moved into. Ideally, that is where he should conduct his duties outside the classroom, but in practice, he is hardly in his office at all, there aren’t enough teachers to oversee the students when he is not within sight of them. So he must be in sight of them as much as he can.

Running a school with one teacher is an impossible situation.

Abdullahi Ahmed is the head teacher of a Local Government Education Authority (LGEA) primary school in Sogene community, located in Umaisha town in Nasarawa state, North-central Nigeria.

Advertisement

Students appear to be fond of Mr Ahmed, but he has a ton of problems to contend with. The most paramount of them, he repeatedly tells this reporter, is the school’s need for more teachers.

“There are only two teachers in this school; myself and one other teacher,” he says, his forehead gathering in a frown.

On a regular school day, he finds himself rushing in and out of classrooms, struggling to teach as many classes as he can before and after recess, leaving him spent at the end of the day.

While Abdullahi speaks with this reporter, he has a difficult time concentrating, Occasionally, a peeking student by the office door would disappear for a minute, only to return with their peer a while later, their excited voices floating above Abdullahi’s as he struggles to speak above the noise.

Advertisement

Even after a lanky boy rings the bell to signal the end of recess, the students show no intention of returning to their respective classes. Some play outside in clusters, some who are in their classes interact noisily while those who are fascinated by the presence of a stranger, hang around the door and window of the office, disappearing when they are asked to leave, only to come back moments later in their numbers.

“They think you are here to vaccinate them,” the head teacher says as he takes his seat again; he had just gotten up for the second time to send the students away to their classes.

Mr Abdullahi resigns himself to the commotion as there is no teacher available to teach the students anyway.

“My colleague is not here. He was called to the LGEA office to attend to something,” he explains.

Advertisement

“Only the PTA teacher is around, and he is teaching a class.”

PTA teachers

Victor/HumAngle.

To make up for the shortage of teachers in his school, the head teacher has employed an extra hand to help with the job. This teacher who is not under the employment of the Nasarawa State government is called a PTA teacher.

Advertisement

Mr Hussaini, the PTA teacher, has to take three classes (classes 1, 2, and 4) on four or five subjects daily. He complains that the workload is quite heavy for him.

“The students are too much for me,” he says, slightly leaning in, so that this reporter can hear him above the noise that has drowned out his class.

Advertisement

When he is not rushing in and out of classes like the headteacher, Mr Hussaini struggles to grade assignments and classwork.

“They give me about ₦ 5000 at the end of the month,” Hussaini says, explaining that the money barely gets him anywhere as he has four children to provide for.

Advertisement

“He is also a farmer and a fisherman,” the head teacher interjects when this reporter asks Hussaini how he gets by on his meagre salary.

“He catches fish very early in the morning, and by 8 a.m., he is already here in time for school, then goes back again by 1 (after school hours) and finishes up,” the headteacher says as Hussaini nods in affirmation.

“We call him PTA teacher because it is the school that takes responsibility for his salary, not the PTA itself,” he clarified.

“At times, we collect ₦ 10 each from students every week, so if it is ₦2500 that we are able to gather at the end of the month, we can say please take this one and go and buy soap to wash your hands,” he says, a metaphorical explanation of the inadequacy of the salary given to Mr Hussaini.

“Most of the schools in areas like ours do the same,” he added.

In another LGEA primary school in Gindin Kade, located in Awe LGA of the state, the head teacher of the school revealed that he had recently employed a PTA teacher in order to make up for the lacking number of teachers in his school.

Scarcity of teachers abounds in Nasarawa LEA schools

“It was just this term that we started employing PTA teachers, and it was because of the way that things were going. You know you have to help yourself so that God can help you,” Ishaka Dano, headteacher of Gindin Kade LEA primary school says in a placid tone.

Unlike the LEA primary school in Sogene, the one at Gindin Kade has three teachers, excluding Dano himself. Each of these teachers has committed to contribute ₦2000 from their individual salaries towards the payment of the PTA teacher that they have employed.

Employing and paying extra teachers out of their own salary (which they complain is miserly) might seem like a huge sacrifice to make for their students but Dano and one of his teachers who spoke with this reporter say that they are doing so for two reasons.

“The stress is too much. How can you teach class 1, and then still go to class 2? We are not robots,” he said, explaining stress as one of the reasons.

“But the most important thing is that the three of us are all from this community and the pupils in the school are our children, so we are just doing this to help our children,” he said.

Grades combined

play outside. Photo: Chigozie Victor/HumAngle.

Teachers remain insufficient. To fill this gaping hole, the schools combine students from different grades in one classroom.

While this may seem alarming as curriculums differ according to grades, the headteachers of both schools say that the combination is merely done in order to curtail the noise that emanates from classes that are without teachers at different times of the day.

“That is why we combine them to manage them so that after we teach one class, then we will say you people should occupy the front row seats so that we will teach the other class. If we don’t do it like that, they will all be noisy. Some might even run away [outside the school premises],” the headteacher of Awe LEA school says.

“Make do”

Nasarwa SUBEB. Abdullahi says he does not mind working in the unconducive state of the office but is more pressed for more teachers. Photo: Chigozie Victor/HumAngle.

“You will be teaching and a child will come complaining to you that he has been beaten by another. That is because there is no teacher in that class,” he says in a pained voice.

While this technique which has been adopted by both schools may seem innovative, Ahmed Abdullahi, the headteacher of the Sogene LEA thinks that there are only so many teachers that can combine different grades and successfully carry out their duties.

“The educational rule only allows for a maximum of 30 or 40 students to be tutored by one teacher but you [teachers] are combining one hundred plus in a class.

“If you give them classwork before you mark it, you have consumed the whole day,” Abdullahi said, going on to make a case for the importance of creating different streams for a particular class if their population is above the teacher-to-student ratio.

Ahmed Abdullahi noted that his school is lacking in a number of facilities and amenities but his primary focus was on the deployment of more teachers to his school.

For instance, when this reporter pointed out the absence of toilet facilities in the school, he insisted that the lack of teachers was a more pressing concern.

“We don’t have enough teachers, how can we say we need more offices? The main problem now is teachers,” he says, instead, moving to another classroom.

The PTA chairman who joins him later comments on the decaying structure of the old office and classrooms as well as the lack of running water in the school. Even though Sogene LEA primary school had recently gotten a new block of 3 classrooms courtesy of the Nasarawa State Universal Basic Education Board (SUBEB), they still lack a conducive environment for all students as there is still a shortage of classrooms.

classrooms in the school. Photo: Chigozie Victor/HumAngle.

“From next week, class one and class 2 will be taking these classrooms,” he said, showing off the board that he has painted with black charcoal in preparation.

At the moment, all that he wishes for are additional teachers. He says this as many times as possible.

“We wrote and wrote and wrote before they built these new classes for us. Before, we had only two,” he says.

“They have brought classrooms and seats, so now, the issue of teachers is our main problem.”

The headteacher at the Awe LEA school says a similar thing.

“I will say we are lucky they came and built this school for us,” he says, narrating how he would tell members of the community to assist him in complaining to SUBEB.

Like Ahmed Abdullahi of the Sogene LEA school, this head teacher at Awe is equally more distressed about the lack of teaching hands than he is about other abnormalities in his school.

For instance, the new building, which he says is barely two weeks old, is already mouldy.

While the two other classes appear to be ok, the head teacher’s office and the class attached to it do not resemble new structures as their walls are riddled with moulds whose distasteful odour hits the nostrils upon entrance, and its walls, made untidy by the greyish decaying colour left on the yellow colour of the walls.

Much like the other headteacher’s resignation with the state of his office, the headteacher at Awe does not seem fazed by the obvious low quality of work which has been done by the builders, he talks instead (alongside one of his teachers) about the inadequacy of teachers.

“Quality assurance department was informed about this issue, and their response was that these days, there is no appointment for employment,” the teacher says.

But while the head teacher at Sogene emphasised solely on the teaching gap in his school, the one at Awe, perhaps because he has more teachers, raises an issue with the teaching aid that the school is provided with.

“We have a serious problem with the teaching aid.”

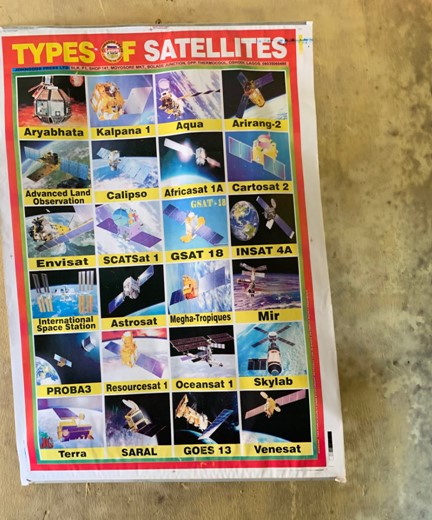

“Now let’s be clear here, this one is something for secondary school,” he says, holding up a poster.

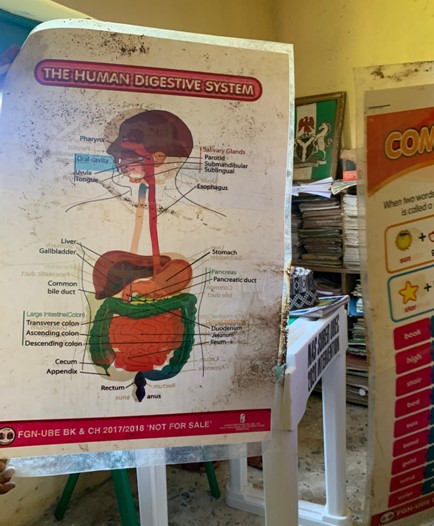

“This one too. Look at it; it is the human digestive system and they are saying that we should teach it in primary school,” he adds.

The head teacher, upset about the teaching aids, goes around the classroom adjoining his, to point out the irregularities in the aids they are being supplied.

The teacher accompanying him tells this reporter that they were recently supplied with Igbo textbooks even though the students do not have the Igbo language as a subject of study or anywhere in their curriculum.

“You will not get mathematics or social studies textbooks, but they will bring Igbo textbooks for you,” he said, suggesting that the abnormality probably happens because the required textbooks have long been distributed to other areas while “the less privileged communities get the leftovers.”

Teacher-to-student ratio

While the headteachers of Sogene and Awe LEA primary schools may be filling the teaching void as best as they can, the students are still not getting the required quality of education.

The LEA school at Sogene has a total number of 162 students while the school at Awe has 150 students currently enrolled, with only two, and three teachers, respectively.

Although there is no “consensus” on a standard student-to-teacher ratio (usually derived by dividing the total number of students enrolled in a school by the number of teachers available to them), “there is wide agreement that younger children need more time and interaction with teachers for a quality education.”

And so going by this notion, one may not be able to say that the appalling lack of teachers in both Awe and Sogene LEA primary schools is short of a general standard, but it is, however, clear that pupils of both schools would not be able to get “quality education” from their schools because even though the class sizes (usually derived by dividing the number of students enrolled in a school with the number of classes in the school) are not as outrageous as the one obtained in a primary school in Kano with 499 students in one class, the students would still not be able to get proper education from their teachers as they (teachers) are forced to combine classes hence preventing them from focusing “more on the needs of individual students and reducing the amount of class time needed to deal with disruptions,” an advantage only enjoyed by small classes, of which the aforementioned school are.

Other things which are instrumental to quality education such as “teacher satisfaction,” which is inclusive of working conditions, salary, staff-to-student ratios, infrastructures and facilities are also lacking in the two schools which were visited.

Zero Recruitment

Unfortunately, the poor number of teachers noted in Sogene LEA Primary school and Gindin Kade LEA primary school are not peculiar to both schools, it is in fact, a statewide issue currently plaguing a lot of public primary schools in Nasarawa State.

The situation is so dire that recently, the Nasarawa State House of Assembly decried the “falling standard of primary education,” and called on the government of the State to declare a state of emergency on primary education.

According to the house, 3,665 primary school teachers have either died or retired between 2011 and 2021 but have not been replaced.

“We need to fill the gap by recruiting competent hands in the interest of our children and the state at large,” Daniel Ogazi, the house chairman on education had complained to the management of SUBEB when it appeared before the committee for its 2022 budget performance, in August.

Mohammed Dan’Azumi who is the chairman of the Nasarawa State Universal Basic Education Board (SUBEB), was contacted through phone, text, and WhatsApp to give comments on the board’s action towards resolving the issue plaguing primary education in the state, but he did not make himself available for an interview.

This report is part of a collaborative investigative series by HumAngle, the International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR), NPO Reports and TheCable, facilitated by the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under its Collaborative Media Engagement for Development, Inclusivity and Accountability (CMEDIA) project, with support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Add a comment