BY JENNIFER UGWA & ANIBE IDAJILI

About 60 Kilometers from Abuja, Nigeria’s federal capital territory, lies Kwamba, a small community of a few hundred people in Suleja, Niger state. According to a local health worker, an estimated 50 per cent of adults in the community are not vaccinated against COVID-19.

Chijioke Favour, a 36-year-old mother of four who lives here, chuckles when asked if she has received the vaccine. “I don’t plan to take it. COVID-19 does not exist,” she says.

Three years ago, the world came to a standstill when the COVID-19 virus swept through international borders, claiming over two million lives globally. There was no cure for the novel virus, and science researchers raced against time to find a cure. After months of research, a vaccine was produced. However, the pandemic had ushered in an era of infodemic.

Advertisement

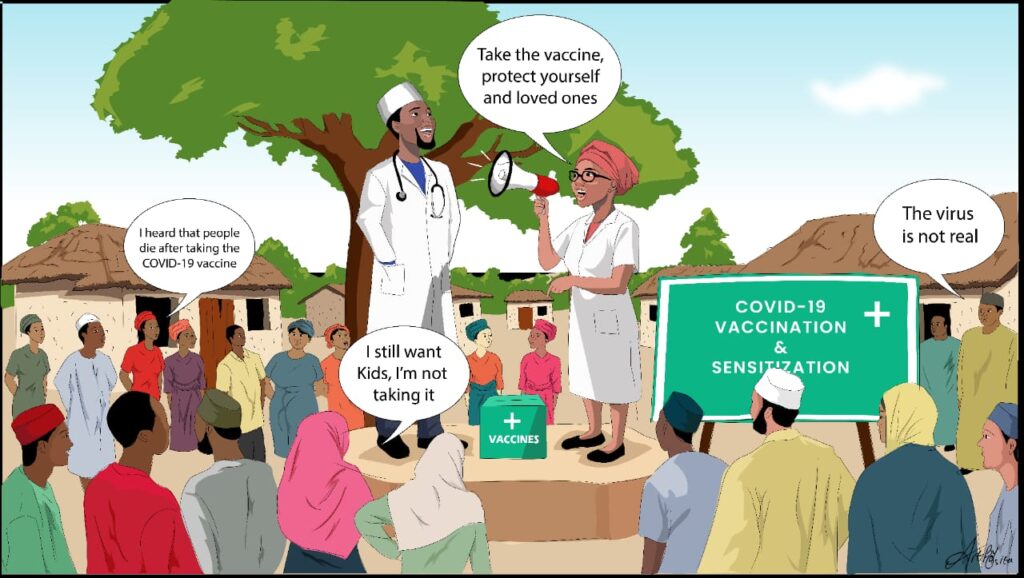

Misinformation like the COVID-19 virus doesn’t exist, rumours that the vaccine was created to depopulate Africa, and other deterrents, including lack of access to vaccines and mistrust for the health system fostered COVID vaccine hesitancy in rural communities across Nigeria.

“There is always a question and a raised eyebrow moment for any vaccine that comes to Nigeria, especially among rural residents,” says Lami Jubril, a health worker and immunisation officer at Suleja General Hospital. “Sometimes, these wrong perceptions are based on religious and social influence.”

Lami says during rural vaccine interventions, health workers are posed with data questions from residents like: “How many dead bodies can the government prove were due to COVID?” Despite what the responses were, findings from more than two dozen interviews across three states — Niger, Nassarawa, Kogi — and the federal capital territory show there still exists high levels of vaccine hesitancy among residents.

Advertisement

In June, the National Primary Health Care Development Agency took to Twitter to announce that 75,693,185 eligible people in Nigeria are fully vaccinated, while 11,878,771 of the total eligible persons targeted for the vaccination are partially vaccinated. Niger state accounts for 20.67% of this number. However, there is a considerable gap in urban-rural vaccination amidst allegations of vaccine racketeering, figures manipulations, and mistrust of the health system.

About 284 kilometres from Kwamba community is 51-year-old Haruna Aliu, in Ungwan Kwangwara community. Like Chijioke, Haruna vows: “No one in my household is allowed to take the COVID-19 vaccine, and that’s that.”

Haruna says previous failed medical trials solidify his stand about immunisations and belief in a “Western agender of depopulation”.

Advertisement

“I am still wary of Western interventions. In 1996, many children died in Kano after taking an antibiotic drug produced by Pfizer called Trovan. I can’t speak for others, but that incident is still fresh in my memory. You cannot dismiss the past because of promises made in the present,” Haruna said.

The botched high-profile medical interventions in some African nations, like Nigeria, have led to a simmering distrust for modern medicine on the continent. Refusal of the COVID-19 vaccine is some of the consequences of these past actions.

For instance, between the 1980s-99’s, Michael Swango, an American serial killer and licensed physician, allegedly administered lethal potassium injections that killed 3 Americans and some Zimbabweans; However, found guilty of killing the Americans, Swango didn’t face trial on the Africans charges.

But mistrust of the health system is only one of the gaps limiting rural community acceptance of COVID vaccines. Around 11.1km east of Ugwan Kwangwara lies the Farin Shinge community with non-existent healthcare facilities. Most dwellers, primarily farmers and livestock herders, have not received the first dose, says Amina Yusuf, the nurse-in-charge of health matters related to Farin Shinge residents at the Military Barracks Clinic. The military clinic is the closest health respondent, about nine kilometres from Farin Shinge.

Advertisement

“Getting villagers interested in travelling to get the vaccines is a big challenge, especially during harvest seasons,” says Amina. The absence of a Primary Health Center undoubtedly belies the importance of immunisation against the virus, and a “majority of the people may never receive a COVID-19 vaccination”.

Umar Ahmadu, a leader in Uchau, a settlement in Farin Shinge, says it is becoming increasingly difficult to persuade residents to take the vaccine if they have to leave the community. He explains that “community members say they do not know anyone who has contracted the disease. So, they do not feel the need to go through the inconvenience of getting their shots in another community”.

Advertisement

Shedrack Muazu, a Kontagora-based health activist, echoes Umarus’s stance. He says the absence of PHCs in the community drastically reduces the urgency and need for the vaccine for residents.

Advertisement

According to Lai Mohammed, the former minister of information, Nigeria annually spends between $1.2 billion and $1.6 billion on medical tourism. But this expenditure is majorly accrued by the rich who can afford to seek medical care in countries with functioning medical sectors. Out of an estimated 30,000 PHCs in Nigeria, only about 20 per cent is functional. PHCs lay fallow, and residents in rural communities like Farin Shinge often rely on the goodwill of non-governmental organisations to access close-range medical services.

Ocholi Okutepa, a former senior medical officer at the Kontagora General Hospital, says the lack of access to PHCs could be linked closely to the apathy and wide acceptance of misinformation campaigns for the vaccine in rural communities.

Advertisement

Conspiracy theories, mistrust in the health system, and lack of access to health services limit the residents of Kwamba, Ugwan Kwangwara, and Fari Shinge, all in Niger state. In Nyanya, a local government under the Federal Capital Municipal Area Councils, religious convictions have a strong influence over Grace Ali, 43, decision.

“Sincerely, with the encouragement from my bishop, I believe that we are alright.” Ali’s bishop is among Nigeria’s top influential religious leaders in Nigeria.

In a profoundly multi-religious country like Nigeria, religious leaders’ perspectives of the vaccine determined members’ acceptance of the jab. Lami notes: “Muslims will tell you it is a lie; then core Christians will tell you that their pastors said they should not collect it.”

Philemon Ogu, 23, a video and content creator who lives in Nassarawa state, says he keeps clear of vaccine controversies. His Youtube channel is one of the most visited and popular handles dedicated to promoting Christian sermons and inspirational words of prominent preachers in Nigeria. But even with over 46.2k subscribers on a single channel and a team of creators – all Christians – Philemon says they are careful not to share content on opinions of spiritual leaders on COVID-19 that could cause “panic”.

A United States research shows that most Americans would trust their clergy‘s advice on COVID-19 vaccines. The situation is not different among the Nigerian Christian group or Muslim group.

Philemon says no one in his family has received the vaccine.

Sunday Agbo, immunisation officer at Nyanya General Hospital, says top on the list of clients –predominantly Christians and Muslims – is the fear of spiritual impacts and side effects from receiving the dose.

“It is tiring convincing people that the vaccine is safe,” says Sylvia Warwan, routine immunisation officer at New Karu, Ado district, Primary Health Care. “The turnout is still low. People still believe that anyone who takes the vaccine will die after one year.”

In the FCT and Nasarawa state, the accumulated number of fully vaccinated people is just over 3 million, with FCT at 965,347 and Nasarawa 2 105,570, according to data from the NPHCDA.

Notwithstanding, hesitancy for the COVID-19 vaccine also arose from false claims by popular and influential persons. One of such influential purveyor of COVID misinformation was Yahaya Bello, the governor of Kogi state. In a video that went viral in March 2021, Yahaya, during a public event, falsely claimed the vaccine killed anyone who took it. The governor claimed he must protect citizens from being used as “guinea pigs” in a global experiment.

As of June, only 469,751 of a target 2.7 million people in Kogi are fully vaccinated against the virus. Testing in the state is also one of the worst, with only five confirmed cases.

“Black people shouldn’t be following these white people to take vaccines against a new disease for which we have little or no knowledge,” says Ruth Abdul, a retired teacher and resident of Agbeji community. Ruth says she only took the first dose after a massive COVID-19 vaccine campaign, adding that she fell sick a few days after. Although doctors could not link her illness to the vaccine, she insists the vaccine catalysed her ailment.

Nigeria ranks 23rd on the World’s list of social media misinformation on COVID-19. “Online misinformation and offline disinformation exist. The latter is the most damaging,” says Victoria Bamas, former team lead and editor for FactCheckHub. Bamas noted that because most people combating disinformation are online, tackling misinformation offline is more challenging, stressful, and time-consuming.”

Vaccine hesitancy is one of the top ten threats to global health, according to the World Health Organisation and even more so in low-and middle-income countries. Nigeria has not recorded an incidence of COVID-19 infection in 2023; the second wave in December 2020 and non-adherence to non-pharmaceutical preventive measures underscores the need for a vaccine.

“We may be out of the red zone, but it is now that we need to sound the alarm on the need for vaccination exercises leveraging pre-existing channels of communication that will connect communities and the health sector,” says Tobin Ekeatte, a consultant and public health physician.

Citizens’ perception of the vaccine is fragmented across local communities. In Ajiolo-Ofalemu community, Abdul Ilemona, a clan leader traditionally known as Gago, prides himself as a local vaccine influencer. Collaborating with immunisation officers like Usman Yusuf, in neighbouring Model Primary Health Care Centre Ajiolo-Abocho, he said there is a record of over 80 per cent vaccination in both communities in the two Kogi communities due to the partnership.

But like Suleja, even with a house-to-house approach, Lami says residents are behind the global vaccination curve.

“It took those that got the vaccine to convince their neighbours to take it after they notice that they [inoculated persons] are not unwell or haven’t died from any complications due to the vaccine weeks later,” he said.

Jennifer and Anibe are Public Reference Beurea, Public Health Reporting Corps 2022 fellows.

Add a comment