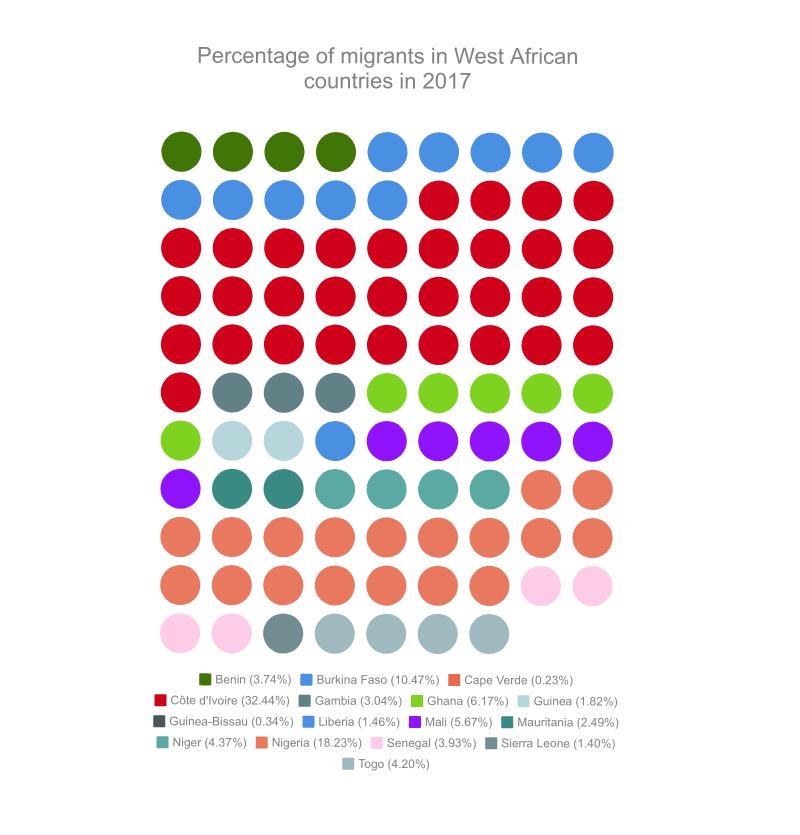

According to the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), migration streams within Africa are larger than those out of Africa.

In a report released in 2016, UNECA said about 31 million of the continent’s 1.2 billion population have migrated internationally, while more than half of those migrating internationally do so within Africa.

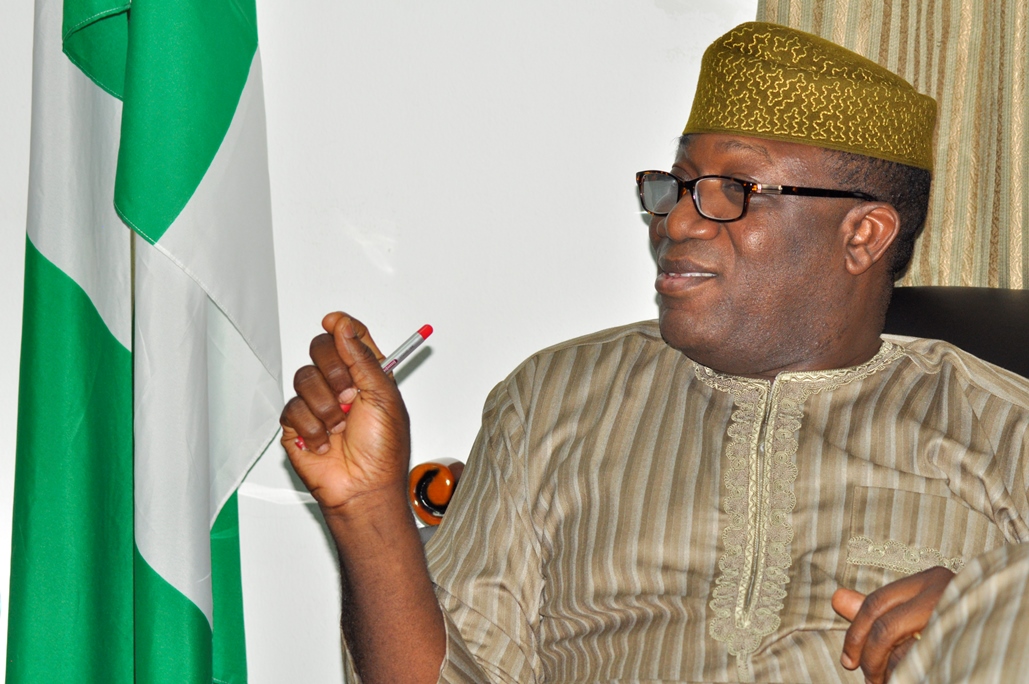

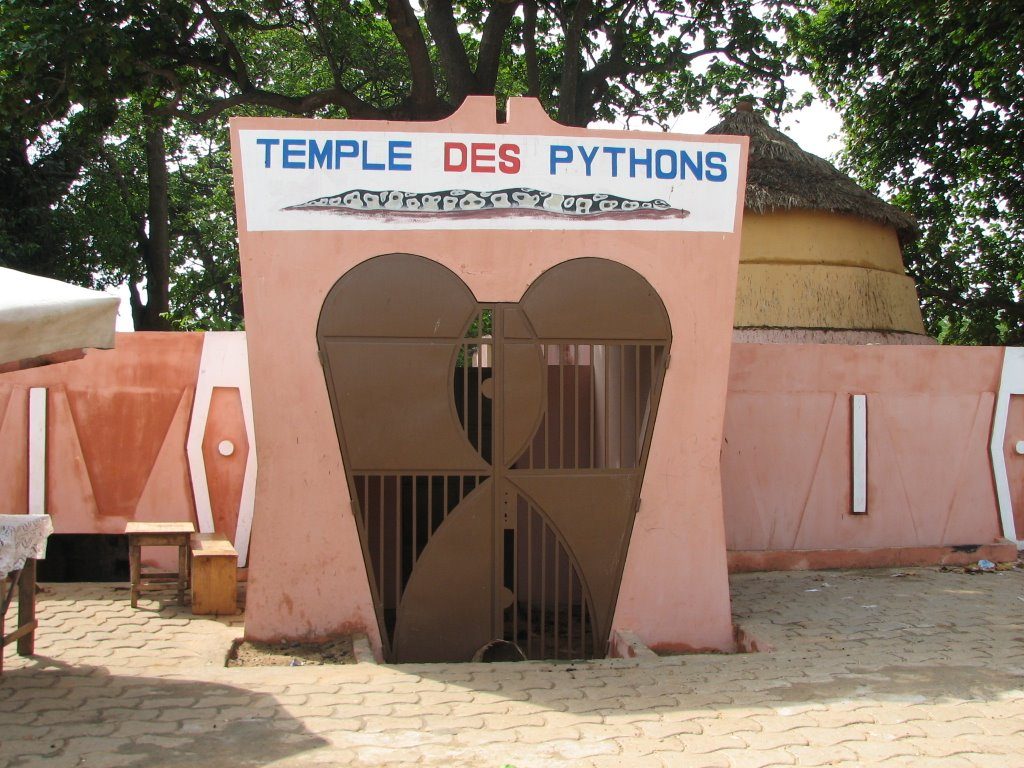

Ouidah, one of the 10 major cities in Benin Republic, is currently hosting many African migrants. 42 kilometres from Cotonou, economic capital of Benin, and 62 kilometres from Seme, the Lagos town which shares border with Benin, Ouidah has a space of 364 square kilometres. Beyond the snakes and the slave that the city is known for, there is the untold story of the economic survival it promises migrants.

Photo credit: Unsenbenin.com

Advertisement

Situated on the Atlantic coast, Ouidah is known for its role in the 17th to 19th century Atlantic slave trade. The Slave Route, a track which slaves were taken to the ships, is now lined with monuments up till the ‘Door of No Return’. The place has been turned into a tourist attraction. Patrice Talon, president of Benin, hails from the city which had a population of 191,688 as of 2012.

Migrants from Nigeria, Ghana and Togo are many in Ouidah. The Nigerians are mainly from Ogoni in Rivers state, which is in the southern part of the most populous black nation on earth. In Ouidah, the Ogoni people are camped in places such as Pharmaci Gbena, Ogoni Mezon and Ouidah Plage.

Lucky Kobel, an Ogoni indigene, has been in Benin Republic since 1999. “So you have been here since democracy returned to Nigeria in 1999?” this reporter asked him. To which he fired back, “Do they have democracy in Nigeria?”

Advertisement

Kobel was surrounded by about six children within the ages of three and 10 years when the reporter approached him on a hot afternoon. The elderly man, who sat not too far from him, was obviously not interested in the conversation, while a woman retrieves clothes from a line beside a tree looked towards the direction of the stranger as she picked the clothes one after the other.

From his countenance, it was clear that Kobel bore so much hatred for the country he migrated from 19 years ago.

Source: United Nations International Migration Report, 2017

Advertisement

OGONI AGONY

His anger could be traced to the plight of the Ogoni people in the hands of the Nigerian government. The Ogonis have been victims of human rights violations. In 1956, Royal Dutch/Shell, in collaboration with the British government, found a commercially viable oil field on the Niger Delta and began oil production in 1958. In a 15-year period from 1976 to 1991, there were reportedly 2,976 oil spills of about 2.1 million barrels of oil in Ogoniland, accounting for about 40% of the total oil spills of the Royal Dutch/Shell Company worldwide.

According to a research by Amnesty International, while the entire Europe recorded only 10 spills between 1971 and 2011, in 2014 alone, there were more than 55 spills in the Niger Delta region where Ogoni is situated.

Worried by the environmental degradation in the region, Ken Saro Wiwa, a Nigerian writer and activist who hailed from Ogoniland, mobilised protest against the government. After battles in and out of the courts, the military regime of Sani Abacha, a Nigerian dictator, executed Wiwa and nine Ogoni leaders in 1995.

Kobel brought out his phone and showed some pictures to the reporter. The actions behind the images sowed the seed of his decision to migrate. “See what they did to our land. See what they did to our leaders.”

Advertisement

He shook his head and that was the end of the conversation. To make him speak further almost became impossible. Among the pictures Kobel showed was an image which depicted Saro Wiwa and the executed leaders, oil spills and destroyed farmlands.

Gahga Jandon, a fisherman and father of 10 children, was one of those who spoke with TheCable during a visit in 2017. TheCable reporter met Jandon who had just returned from Bonny River, about 30 kilometres away from his home in Gokana, with nothing to show for hours of fishing and paddling.

Advertisement

CHANGED LAND, CHANGED BUSINESSES

Perhaps it was the fear of having a similar fate which made Kobel relocate from his ancestral land.

Many fishermen in Ogoniland lost their fish farm and major source of livelihood to oil spills which turned homes to pools of black blood. Fish was no more, periwinkles were wrinkling, and crabs became melly in their holes.

Advertisement

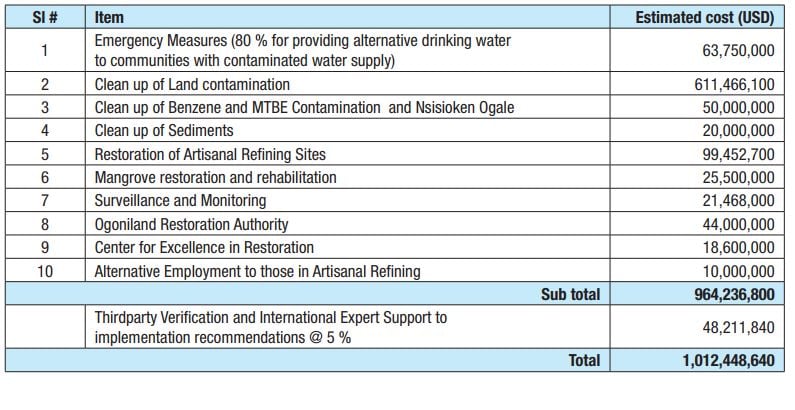

Hopes were high when, in 2016, the Nigerian government announced the flag off of the Ogoni cleanup project. $1 billion was reportedly set aside for this exercise. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) had recommended the clean up of the heavily polluted land to restore the ecosystem to what it used to be in other to secure the peoples’ source of livelihood.

On June 2, 2016, Yemi Osinbajo, vice-president of Nigeria, launched the clean-up project but it has been on hold since then. The likes of Jandon have decided to hold on but his counterparts are outside the region seeking means of survival.

Advertisement

An Ogoni indigene in Ouidah who refused to disclose his identity said his people do a lot of things to survive.

“Some of us go to the sea to assist the fishermen, while others do different kinds of menial jobs,” said the man who deals in second-hand clothing items.

“As you can see, I’m a trader.”

Investigation also revealed that there are economic refugees from Nigeria in Benin, but there is no proper documentation to know their exact number.

Daniel Fiadonu, a Ghanaian who has been in Benin Republic since 1985, confirmed what the Ogoni indigene said when the reporter caught up with him at Avlekete Plage, a Ouidah community situated some three kilometres from the heart of the city.

“Many Ogoni people have worked with me. I have lost the count of those who have been here since 1985 when I got to this place,” he said.

“I receive people from different countries here. The nature of the job makes people to come and go. Right now, I have some Togolese and I am about welcoming them here.”

Fiadonu migrated from Lome, capital of Togo, to Avlekete Plage. He moved after the Togolese government sent some foreigners out of its country.

“When I had problem in Togo, a friend of mine invited me here. He said I should come over and fish. I brought my fishing materials here since 1985 and I have been doing well,” he said.

“Business is better here than Ghana because of the joining place of the river and the ocean.”

Asked to speak of his challenges, he said, “At times, the people of Benin take advantage of us because it is their land.

“I remember when we first came to this country, we settled at Heo, a village which is about two kilometres from here. The people were hostile but we later realised that one of the women there was my aunt.

“She was the one who found out after taking time to study us. After the people found out, they invited us over and we moved to Avlekete Plage.”

THE SEASON IS OVER!

A Togolese simply identified as Kwesi said he and some of his colleagues decided to move to Benin because the fishing season was over in Togo.

“When the season is over in Togo, we come down to this place. We’ll stay here for sometime before going back,” he said.

“The first season in Togo is from February to May. The second season is between September and December. So, we’ll stay here till early February. We are used to such system. That’s why we are fishermen.

John kwesi, a Ghanaian, said he enjoyed working with Nigerians and Togolese. He told the reporter that he had spent just two months on the site and that he would return to his country after meeting his target which he refused to disclose.

Avlekete Plage is a largely fishing community. It has a public hall, health center, and a school, where children of the fishermen attend. All the houses in the community were built with palm fronds.

Although there is a road from the community to Ouida and Cotonou, the fastest means of transportation is through water. Traders, residents cross the Tor River for a token of 100CFA (N67 equivalence).

On my way out, I opted to take the river. As the passengers who were making their way into the village disembarked, we boarded the boat. There were at least 23 persons on board. The boy paddling it should be possibly in his 20s. A few minutes into the journey, I was asked to stand. When I inquired to know why, I was told it was to stabilise the boat. The traders on board were comfortable but I was not.

No life jacket was offered just in the event the unfortunate happened. Thoughts raced through my mind. The boy paddling the boat reached for his pocket and brought out his phone and the next I heard was ‘Money fall on you… Paparazi follow you,’ lines in the song of Davido, Nigerian Hip-Hop star.

As the dark-skinned young man sang along and lightly swung his head about, I could only hope that he won’t fall in the water! I wanted to ask him if he was aware that the musician was the biggest winner at the 2017 ‘Sound City MVP Awards’ but I knew I needed an interpreter, so I decided to enjoy the scary once-in-a-lifetime experience. Like Kwesi, I reckoned that I was on the move too because the season is also over for me.