Residents fetching water from an untreated dam at El-waziri community in Bosso LGA, Niger state

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) is integral to epidemic preparedness and response globally. But in several communities in Nigeria, access to clean water and sanitary facilities is a major challenge, thereby undermining the country’s ability to prepare and respond to outbreaks of diseases effectively.

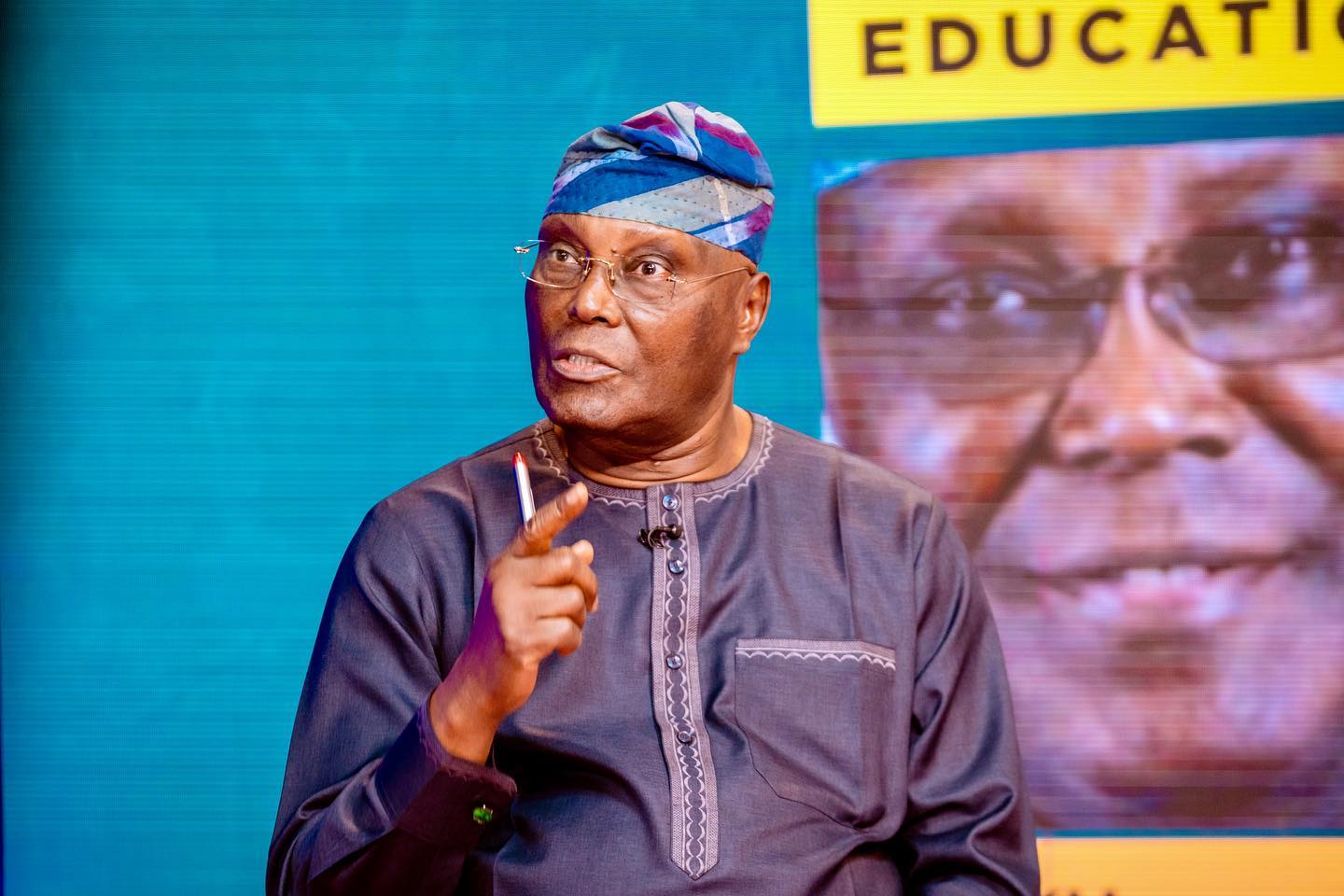

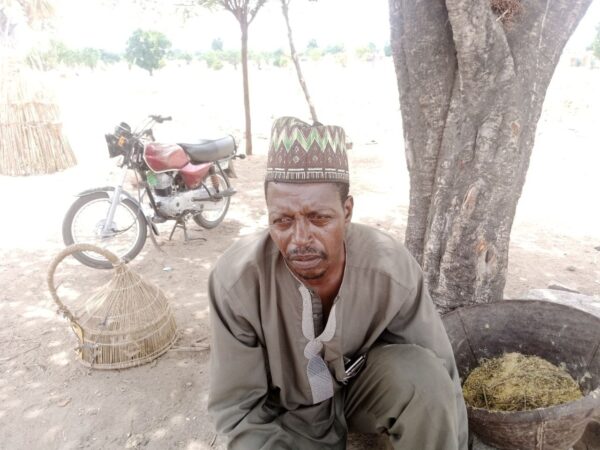

On a sweltering afternoon in April, Aminu Abdullahi twisted and turned as he struggled to fill his bucket with brownish water from a dam. The putrid smell oozing out of faeces and urine deposited around the dam could make a first-timer to throw up easily.

But Abdullahi was fixated on one thing — getting water from the untreated dam, which is the only source of water for him and other residents of El-waziri community in Boss LGA, Niger state.

“This has been our plight for the past few years. We know this water might not be safe for us, but who cares? You have to survive first,” he told TheCable.

Advertisement

But water is not the only hygiene-related issue confronting the community. The majority of the households lack toilets, forcing them to embrace open defecation. Around the community were indiscriminate dumpsites and clogged drainages with houseflies having a feast.

Several residents of the community told TheCable that they were disturbed by the trend.

“Honestly, this environment needs more improvement; we are vulnerable to diseases,” Amina Ahmad, one of the residents, said.

Advertisement

Idris Alhassan, the community leader of El-waziri north in Bosso ward, said his family and others rely on “alum and God” to avoid falling sick as a result of the water they are drinking.

Just like the residents, health workers at Bosso Primary Health Centre (PHC) are also bearing the brunt of the water scarcity. Ajayi, the officer-in-charge of the newly-built facility, said while they have no issue with other sanitation facilities, water is a challenge.

“We have a borehole but the engine is faulty. So, water is a challenge for now,” she said.

STREAM TO THE RESCUE — THE PAIKORO LGA STORY

Advertisement

Like residents of Bosso LGA, communities in Paikoro LGA in Niger are also facing poor sanitation challenges owing to water shortage. At Tutungo Jedna, residents rely on stream water for drinking and other domestic use.

The problem is usually worse during the dry season when the streams dry up. During such period, residents often dig holes around the streams to be able to get water. When TheCable visited the area, open defecation was a norm.

“We don’t have toilets, so we defecate inside the bush. I don’t know if anyone has died of cholera but we have had instances of people struggling with some kind of illness; I don’t know if the disease is due to the water we are drinking,” Maryam, a resident, said.

“We want the government to help us with drinking water, hospital, school, toilets, and electricity. The few taps we normally fetch water from before are no longer functional.”

Advertisement

Aliyu Yakubu, a community leader, said the two boreholes in the area have not been working optimally due to engine-related issues, hence the dependence on water from the stream.

“After our enquiry with the person that will repair the two boreholes, we learnt it would cost us N800,000 to fix the engines but we don’t have money for that,” he said.

Advertisement

Yakubu added that one of the available WASH projects constructed in January stopped working a few weeks after.

This is despite the fact that Niger is one of the 13 states with suspected cases of cholera in 2023, according to the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC). The other states include Abia, Anambra, Bauchi, Bayelsa, Cross River, Ebonyi, Kano, Katsina, Ondo, Osun, Sokoto, and Zamfara. Niger also made the list of the top 10 states with cumulative cases of suspected cholera.

Advertisement

Yet, access to WASH facilities, which is critical in combating the disease, is poor. The NCDC, in its latest situation report, said as of April 30, a total of 1,629 suspected cases of cholera — including 48 deaths — have been reported from 13 states, with children below the age of five the most affected.

The experience in Niger is not different from communities in other states responding to cholera and other hygiene-related outbreaks in Nigeria.

Advertisement

NIGERIA’S STRUGGLE WITH WASH

In its 2022 report, the World Health Organisation (WHO) said poor sanitation is linked to the transmission of diarrhoeal diseases such as cholera and dysentery, as well as typhoid, intestinal worm infections and polio.

“Some 829,000 people in low and middle-income countries die as a result of inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene each year, representing 60% of total diarrhoeal deaths. Poor sanitation is believed to be the main cause in some 432,000 of these deaths and is a major factor in several neglected tropical diseases, including intestinal worms, schistosomiasis, and trachoma. Poor sanitation also contributes to malnutrition,” the report said.

The World Bank also noted that safely managed water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services are an essential part of preventing and protecting human health during infectious disease outbreaks.

“One of the most cost-effective strategies for increasing pandemic preparedness, especially in resource-constrained settings, is investing in core public health infrastructure, including water and sanitation systems,” the organisation said.

But in Nigeria, investment in WASH is not sufficient, thereby exposing residents to hygiene-related diseases.

Poor access to improved water and sanitation in Nigeria remains a major contributing factor to high morbidity and mortality rates among children under five, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) said. The organisation also estimated that only 26.5 per cent of Nigeria’s population use improved drinking water sources and sanitation facilities while 23.5 per cent defecate in the open.

This global body said the use of contaminated drinking water and poor sanitary conditions result in increased vulnerability to water-borne diseases, including diarrhoea which leads to the death of more than 70,000 children under five annually.

In 2018, former President Muhammadu Buhari declared a state of emergency in the WASH sector and also launched the national action plan for the revitalisation of the sector. At the time, Buhari had said the initiative was to improve access to clean water and end open defecation by 2025.

In spite of the initiative and other similar efforts by the government, access to WASH facilities still remains a challenge for Nigerians, particularly those in rural areas.

In 2021, TheCable had revealed how residents in communities across Kano and Bauchi lived in unsanitary conditions — despite being among the states worst hit by cholera in the country at the time. Findings from the investigation also showed that some WASH projects that would have addressed the situation were either abandoned before completion or stopped functioning a few months after completion.

A similar investigation by TheCable further detailed the inability of Lagos residents to access water from government pipelines despite the allocation of N12.22 billion to the state’s water corporation to develop the sector.

IMPLICATIONS OF LOW WASH FUNDING TO NIGERIA’S EPIDEMIC PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE

WASH is a critical component of NCDC’s response to disease outbreaks in Nigeria. During the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, there was an emphasis on regular handwashing and good hygiene, but the lack of water made this impossible for many Nigerians, according to a report.

In its April report, the NCDC identified the lack of WASH facilities as one of the challenges affecting its response to cholera. Others, according to the report, include: “open defecation in affected communities, lack of potable drinking water in some rural areas and urban slums, poor hygiene practice in most cholera affected communities, inadequate health facility infrastructure and cholera commodities for management of patients (Ringer’s lactate and ORS), inadequately trained personnel in states for case management, and poor and inconsistent reporting from states”.

Speaking on this, health experts and policy analysts told TheCable that the country’s low investment in WASH is a reflection of its poor epidemic preparedness and response.

Iorhen Akase, an infectious diseases physician at the College of Medicine, University of Lagos (UNILAG), said it is unfortunate that the progress made on WASH during COVID-19 has not been sustained.

“There is no serious epidemic preparedness without putting in place structures for water. How well are we doing? Clearly not as well as we should be doing. COVID-19 brought a lot of gains, and one of them is the awareness around the importance of WASH as well as infection prevention and control which is important to epidemic preparedness. However, some of the gains recorded have not been maintained,” he said.

“If you go around certain hospitals, we have health facilities that have made arrangements for wash hand basins, but some of them are not dispensing water anymore. There is still a lot to do to make water systems within cities and communities more sustainable. We know that building boreholes is not a sustainable way of doing this. Clearly, COVID created a window of opportunity to consolidate on these things but nationwide, we are still a lot behind.”

Also speaking, Tanimola Akande, a professor of public health at the University of Ilorin (UNILORIN) and former national chairman of the Association of Public Health Physicians of Nigeria (APHPN), said “funding of infrastructure for water and sanitation is very poor”.

“Government at all levels in Nigeria are not doing enough to fund WASH. Individuals also have roles to play but are challenged by the high rate of poverty and ignorance. In 2022, about 70 million Nigerians had no access to basic drinking water, and 114 million had no access to basic sanitation,” he said.

“The implication of poor funding of WASH in Nigeria is that a lot of preventable communicable diseases like outbreaks of cholera will continue to occur. Nigeria’s preparedness to address such epidemics is very low, mainly due to poor funding. Response to outbreaks of epidemics is also not optimum in Nigeria because of poor funding. Quite a number of deaths are recorded during such epidemics that would have been prevented with adequate funding of government bodies that are responsible for epidemic preparedness and response.”

This report is supported by Nigeria Health Watch.

Add a comment