That Monday morning when headteacher of Girei primary school 3 in Adamawa state announced to his pupils that henceforth, they would be served a bowl of meal per day, the excitement blew the children off, and right there on the assembly ground, they started chanting prayers for the president whom they were told had made provision for this.

The headteacher simply identified as Aliyu could not hide his joy as he told the kids, whose houses were few metres away, to run home and get their bowls. Over the years, one of Aliyu’s worries as a teacher and administrator was how he could improve on pupils’ enrolment and attendance. When he first heard of the government’s National Homegrown School Feeding Programme over the radio, he never thought his school would be among the beneficiaries.

“I got to school that morning to meet two women, bearing buckets of food,” he said.

It came to him as a surprise as no one had informed him, not even the supervising local government education authority (LGEA). One of the aims of the federal government at the inception of the project was to interact directly with food vendors, and doing away with any intermediaries that might compromise on the goals. Aliyu would later realise this.

Advertisement

“They told me they are going to feed about 60 pupils from primary one to three, and I thought we could improvise so the thing would go round, and maybe get to the other classes” he continued.

When pupils returned with their bowls, the influx left the headteacher and the vendors confused.

“These kids came in triple fold. Those who were at the assembly had gone to call on those who didn’t plan to attend school that day and the whole thing was just overwhelming.”

Advertisement

At the end of the day, the food could only go round those in primary one and primary two. And, since the vendors told Aliyu they should be around for the next 20 days, the headteacher appealed to other pupils, promising them a rotation that would put them in turn the following day.

Expectedly, the assembly ground was crowded the following morning with the school witnessing an unprecedented punctuality and attendance.

“It was the first time in a long while we saw pupils happy about school in this manner. With their bags hanging on their shoulders, they held their plates curiously.”

Aliyu began losing hope when barely five days into the feeding, one of the vendors stopped coming because “she didn’t get money to cook for the pupils.”

Advertisement

The same excuse the other vendor would give, just days later.

PUPILS HAVE ‘STOPPED PRAYING FOR BUHARI’

Except for Aliyu and some of his teachers idling around, the school was almost empty weeks into resumption for the second term that TheCable visited.

Although the feeding had stopped before the end of the previous term, Aliyu had continued telling his pupils not to worry that better days awaited them in the second semester.

Advertisement

“They all came in their numbers first day of resumption, but sadly food vendors didn’t show up,” Aliyu explained in a depressed tone.

“Throughout the rest of that week, the pupils who used to pray for the president for feeding them saw no need to do so again. And sadly, most of them stopped coming to school.”

Advertisement

At the neighbouring Girei Primary School 2, the experience is similar with Rasheedat Mohammed, the school’s headteacher. She had been reading in the newspaper that the feeding was ongoing but couldn’t understand why vendors had stopped coming to her school.

“January, second term was the last time food was brought here,” she said.

Advertisement

“You know the pupils come to school with their bowls, and now when it’s break time, you will see them coming around my office, peeping to know if vendors brought food for them. They all have been so disappointed, and this has affected attendance.”

It is not a different story with Dubeli Primary School, Yola, where pupils were fed for only 10 days in 2019. Abdulmalik Kabiru, the headteacher, complained that the vendors attached to his school were not coming regularly within the 10 days the feeding lasted.

Advertisement

“I have about five vendors. If three came on Monday, maybe only two would come on Tuesday and sometimes just one of the vendors would come,” he said.

In those 10 days, the school had had an increase in enrolment that “even those whose names are not on the school register were coming to classes.”

“Why did the government stop this feeding that has been encouraging the pupils?” Kabiru asked.

HUNGER, SICKNESS… PUPILS BACK WITH COMPLAIN

At least N5,000 goes out of Rafiu Modibbo’s pocket every month to buy food and drugs for his pupils in Yelwa primary school.

Before the free feeding project started, the headteacher, on a daily basis, attend to tens of pupils who come to him to complain of being sick.

“There is no sickness anywhere, most times, it is hunger,” Modibbo said.

“When a pupil comes to tell you he is sick, I would ask what the matter is and he would say stomach ache. I will buy drugs and when I ask if the pupil is fine after using the drug, he will shake his head, grumbling. But, when you buy him food, the ache disappears immediately. I set aside about N5,000 from my salary every month to attend to this.”

Most of the pupils, Moddibo explained, do not take breakfast before coming to school. It was a sort of relief for the headteacher when the government feeding got to his school, and he would ensure none of his pupils was left out.

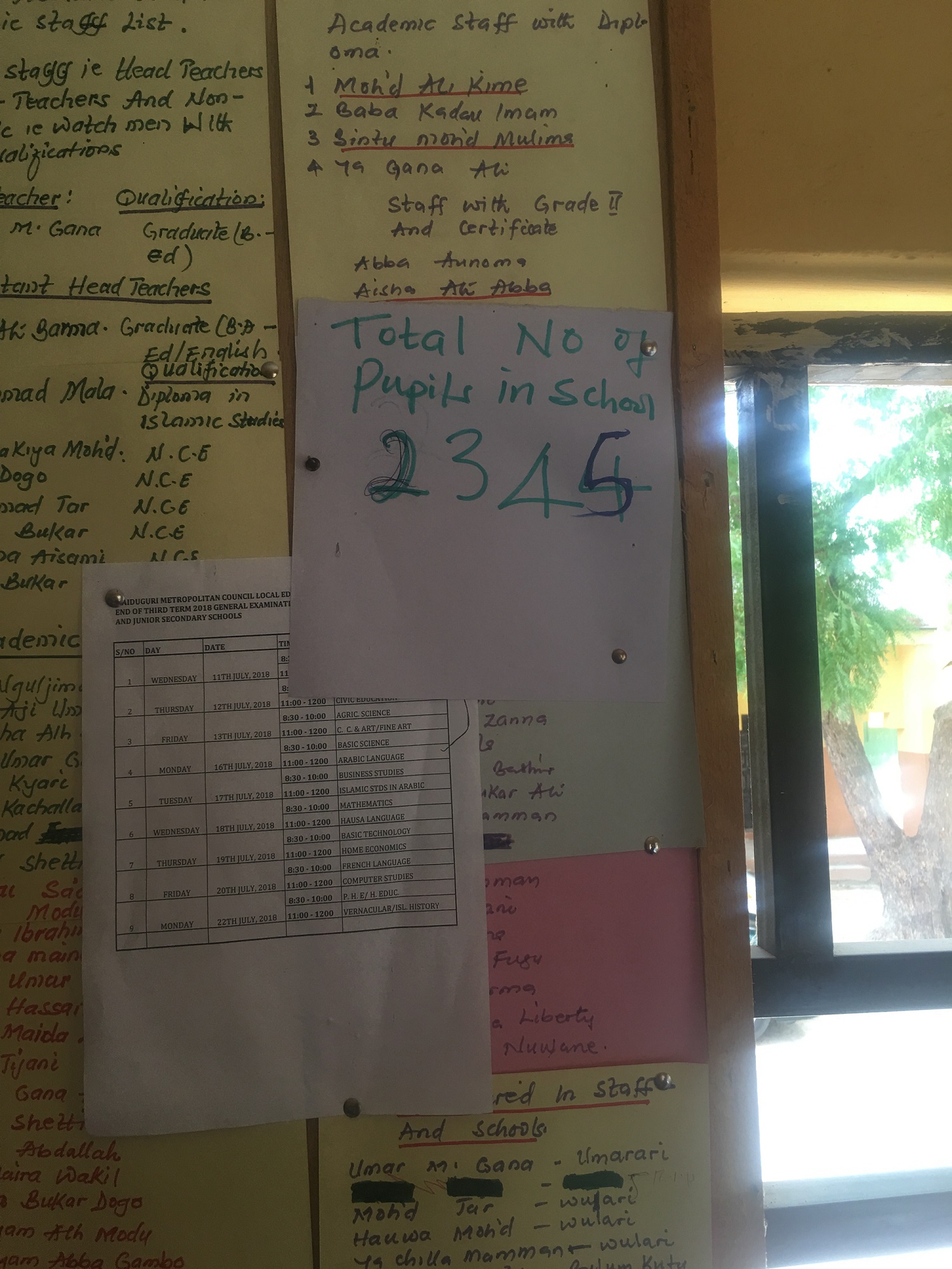

Eleven vendors were initially attached to the school of about 3,000 pupils, and when Moddibo complained to the state’s coordinator, additional nine were added to make them 20.

“The week the feeding started, I saved my money,” Modibbo said.

The food has stopped coming, and Modibbo’s pupils are back with stomach ache complaints.

“It is disheartening that right now, we are back to square one. They don’t even want to come to school again. Those who manage to come are already feeling sick, and this is affecting the learning process.”

MY KIDS HAD FULL EGG FOR THE FIRST TIME

Many parents, who are mostly low-income earners, felt relieved the moment government started feeding their wards and children. Before then, it was difficult getting the kids to go to school as they are back home early, jumping out on the streets to play.

“Even the one I thought was not old for school would pick his bowl and follow his elder ones to school,” Maimuna al-Bashir, a mother of six, said.

From the little she makes from her petty business, al-Bashir, a third wife to a local farmer, could only make provisions for a meal a day for her kids. This meal, she would prepare in the evening so the kids could eat and then go to sleep.

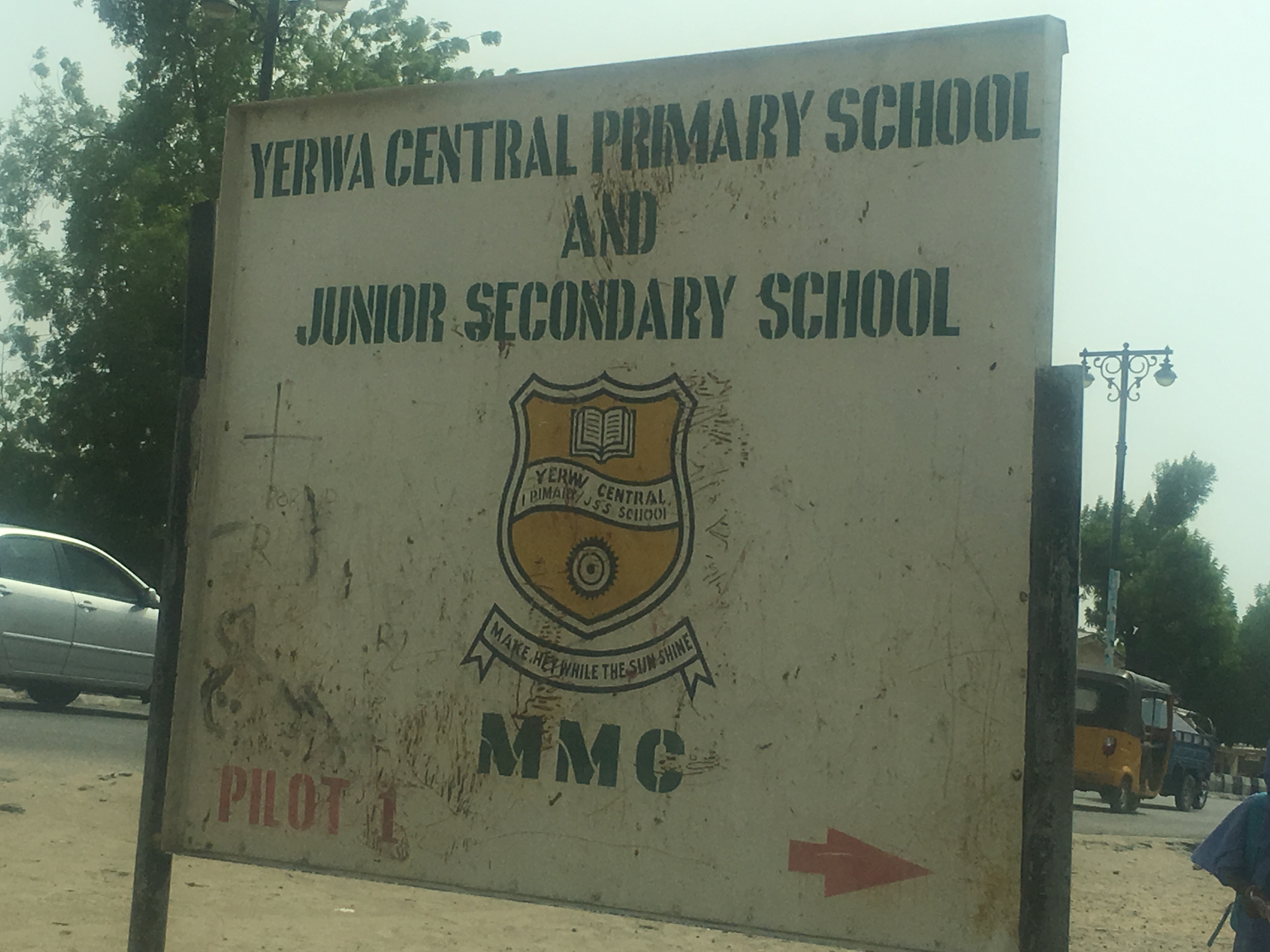

Her kids started having two meals per day when the government feeding started in Yerwa Central Primary School in Maiduguri, Borno state.

“The food I give them at home is without meat, fish or egg because I can’t afford it. But they were getting these things in school and I felt so happy. Every Thursday, their meal comes with a full egg. This is the first time my children will be having to eat full egg.”

Two of al-Bashir’s kids have stopped school since the feeding came to a halt.

“The vendors stopped after supplying for 10 days,” Umar Garau, the school’s headteacher, who kept a record explained.

“I got eight vendors here who brought food for 10 days. When I didn’t see them again, I called one of them and she told me they’ve not been paid.”

The curious headteacher made his way to the bank to ask why vendors were not paid, and the bank official simply told him the fault is government’s that was yet to release money into their bank.

DISPLACED PUPILS BACK TO THE STREETS

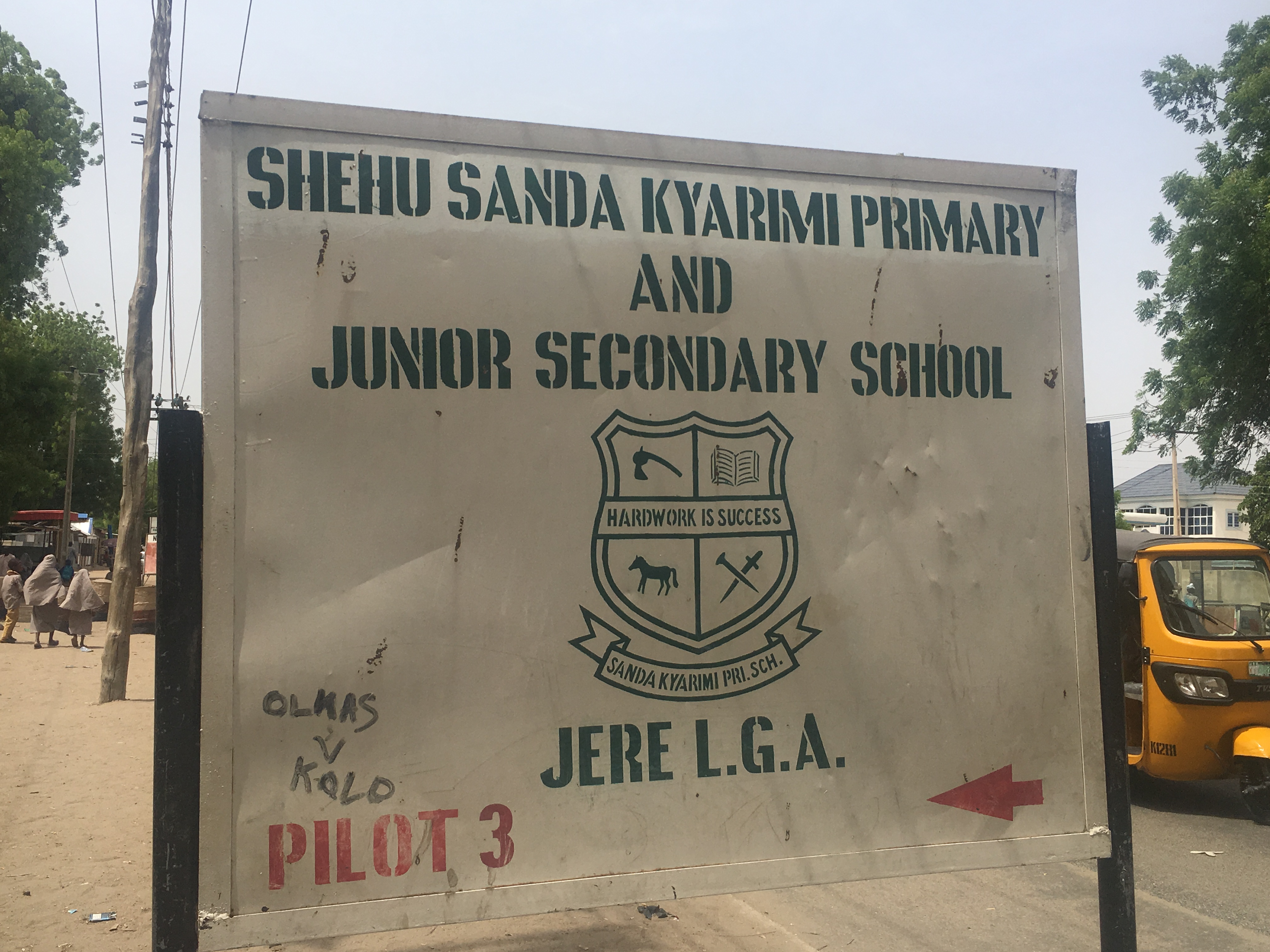

Among the more than two million people displaced by a decade-long insurgency in the northeast are children of school age who are always seen roaming about Maiduguri where there are a number of camps for them. About a hundred of these children got enrolled at the Shehu Sanda primary school the week the feeding started.

“Some of them, their villages have been attacked five years ago and since then they had stopped school,” Abubakar Ahmed, the school’s head teacher, said.

“You will see them with their bowls begging for alms all over the streets. But when some of them in this area learnt we had food in the school, they rushed to me and my teachers that they want to register in my school. Even when I know the food might not be enough to go around, I was excited that at last, there is a motivation for this displaced kids.”

On the fifth day of feeding them, Ahmed said the displaced kids almost made 25% of attendance. The kids have since returned to the streets, and this turn of events, Ahmed described as a setback in the ongoing reconstruction and resettlement efforts in the region.

“When you look around, some of them roaming past still peep to see if the food is back,” he added.

A widow at the displaced persons camp in Dalori, who simply identified herself as Hauwa, said the food given at the camp is not always enough and since the feeding stopped in the school, they had no option than to go beg on the streets.

“Adults can still hold themselves, but the children can’t survive with this food given them promptly,” she said.

‘WHEN WE SEE ALERT, PUPILS WILL GET FOOD’

At inception, the government had said the ripple effect on the feeding would create 1.14 million jobs; 290,000 jobs from community caterers, 580,000, jobs from support caterers; and 274,000 for smallholder farmers.

As a vendor, Adama Umaru would indeed be one of the beneficiaries in Maiduguri. The middle-aged woman who sells food in a kiosk around Post Office had filled the form and subsequently area found herself on the list of vendors to supply food to one of the schools. It was a motivating experience for her as she got more money as much work than she would at her Post Office kiosk.

According to her, they were told a second tranche of the money would be given them, but they have waited weeks and nothing has been forthcoming.

“It is not our fault that we have stopped cooking for the pupils. Lack of money has been the issue. But I know they have our bank account, when we see the alert pupils will get food,” she said.

Hassana Maliki, a vendor in Yola, lamented the challenges they had with the bank in the time the feeding lasted.

In Yola, money is paid into FCMB bank which has just one branch in the town.

“I don’t know why they couldn’t spread it across other banks that have more branches here,” she said.

It took Maliki and some others three days to access the money, and this meant they couldn’t deliver food to the schools at the appropriate time.

POOR SUPERVISION

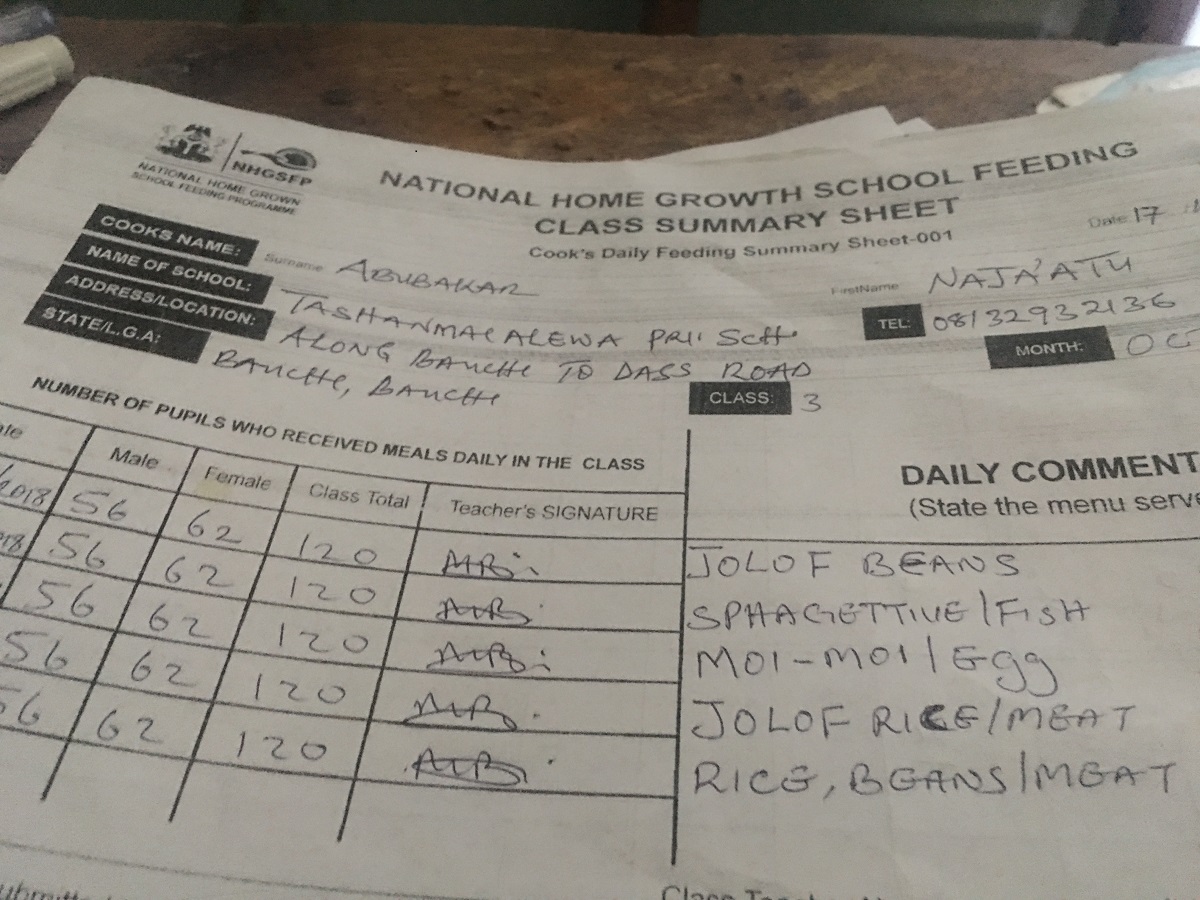

A common complaint across most of the schools is that the programme has not been placed under strict supervision, and in most cases no one is in sight to hold responsible. Many of the head teachers who spoke with TheCable said they were neither informed by the State Universal Basic Education Board (SUBEB) nor the LGEA when they just saw vendors bringing food. This made it difficult for some of them to keep records, and know which quarters to report the defaulters.

Chonta Bulus, one of the teachers at the Tafawa Balewa primary school in Bauchi, explained that when they first saw the vendors, they reached out to the LGEA and nobody was giving the needed information.

“At least if you are assigning the school these vendors, we suppose to know what they are meant to deliver so we can monitor and ensure things are done right. We were the ones who improvised for a register and told vendors who brought food to mark their names,” she said.

In the days that the feeding lasted, Bulus said not once did any official come around to check if the food had been delivered, and especially if they brought the right things.

“For instance, we heard they are also supposed to provide fruits, but these vendors didn’t bring that, and who do we report to? There were days they brought food without meat or fish, there were days the quality of the food was below standard.”

‘WE DON’T HAVE VEHICLES TO MOVE AROUND, GOVT OWING OUR WORKERS’

Adesanmi Abimbola, national coordinator of the project, had said there is a federal monitoring structure where they engage locals who serve as monitors and are called verification officers. The federal government in partnership with the state government is also expected to make provisions for secretariat and logistics for the project in the state.

But, Usman Mohammed, the finance officer for the project in Adamawa state, said one of their biggest challenges is lack of vehicles to move around for supervision.

“We have monitors mainly selected from the School Based Management Committee (SBMC), but we still need vehicles to be able to move around,” he explained.

“Yes, these people give us weekly report, but to be honest if we can get monitoring vehicles it will be easy for us to go everywhere and we won’t have any excuse that would stop us from the supervision job. We also expected that the federal government provides us with offices and even accommodation, but we are still struggling with the overhead cost.”

Usman said monitoring officers engaged this year are being owed allowances by the government.

He also explained that the state has received seven disbursements since the project started. Each of the disbursement was to feed the pupils for 10 and in some cases, 20 days.

“First disbursement was for 10 days and the total number of vendors we had then was 1, 671, and then the total number of pupils fed was 140,823,” he explained.

“So far, we have received seven disbursements, and we look forward to more.”

‘THERE ARE SOME FRAUDULENT ACTIVITIES’

A senior government official who did not want to be quoted said payment was stopped in some places over discrepancies, especially after the office of the auditor-general carried out an audit.

“This is federal government money, and so we need to monitor it well. There are some fraudulent activities we discovered. For instance, some submitted a list of 200 schools but when the auditor’s team went round, they found 100 schools. In cases like this, we had to stop providing the money,” he said.

‘NO OFFICIAL COMPLAINT MADE’

The All Progressives Congress (APC) led government, as part of its campaign promises to provide a meal per day for public school pupils — had launched implementation plan for the National Homegrown Feeding Programme, one year after it assumed power.

Placing emphasis on four main benefits, Vice-President Yemi Osinbajo, whose office pioneered the project, listed improvement of school enrollment and completion as first, adding that the project would also curb the current dropout rates from primary school estimated at 30% and thereby reduce child labour. Out of the N6 trillion 2016 budget, N500 billion — of which N93.1 billion is mainly for the feeding — has been devoted to the social investment programme, Osinbajo had disclosed at the launch in June 2016.

Two years after, the government said it had spent N49 billion on the project and the value chain had offered additional benefits of job creation and increased livelihood outcomes for both cooks and small holder-farmers, hence improving livelihood and the local economies.

While schools enrolment increased in the three states, things were back to where they were days the food didn’t come, and the essence of the project may have been defeated.

Abba Ibrahim, a community head in Wulari area of Borno, feared the government is able to sustain the feeding.

“It is a good initiative, and our children are enjoying it, but the way it comes and goes, I am afraid the government may lose interest soon,” he said.

“One, not all the schools are covered, and secondly those who are on the list don’t get this food regularly.”

When contacted, however, Ismaeel Ahmed, senior special adviser to President Muhammadu Buhari on social investment programmes (SIP), said the office is yet to receive any formal complaints from any of the states.

“You know these schools are owned by the state and local governments, and so we can’t just access them like that without going through the states. As much as I know, none of our focal persons has written to say the feeding has stopped,” he said.

This investigation was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR)

Add a comment