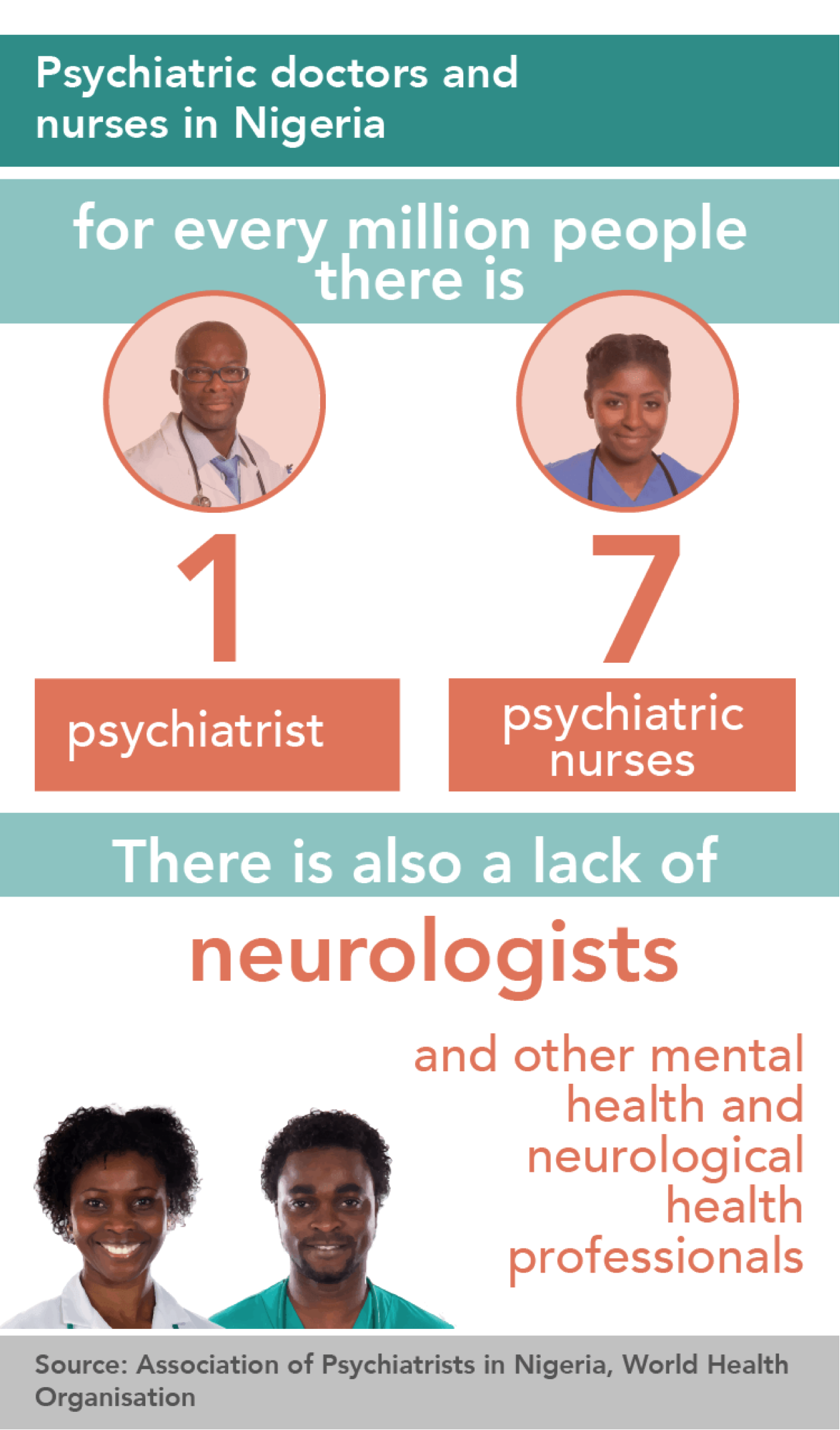

Mental health’s patient-worker ratio is dismal in Nigeria; it’s about one psychiatrist to one million people, according to the 2013 National Policy for Mental Health Services Delivery. The country also has about only five psychiatric nurses per 100,000 people, with even fewer neurologists and health professionals like clinical psychologists, social workers, neuro physiotherapist and occupational therapists.

Nigeria’s mental healthcare needs are clearly in dire straits, leaving most people with mental illnesses untreated. In fact, according to the country’s policy for mental health services delivery, only 10 percent of people living with the illnesses receive treatment. The reality is, there are simply not enough mental healthcare practitioners to take care of the mentally ill people in Nigeria. Records show that mentally ill people are over four percent of the entire population of the country.

A mixture of the acute shortage of mental healthcare workers, the inadequate facility to handle mental health illnesses, Nigeria’s high level of religiosity as well as the pervasive poverty in the country enable the spiritualisation of mental illnesses.

Advertisement

Often times, spiritual leaders, including pastors, Imams and traditional spiritualists, are the first point of call once there is a manifestation of any signs of mental illnesses. After the first part of this series on mental illnesses which highlighted the dominance of the the false narrative that mental illness is a spiritual, several people reached out to say that is impossible not to spiritualise mental illnesses.

“In my opinion, mental illness has various causes which are not necessarily spiritual. However, I won’t totally rule out that a person can be under the oppression of the devil as case in the bible prove this,” a woman who simply wants to be identified as Temi, says.

Another woman, Chidinma Ada, insists that “mental illness could be programmed – like a (spiritual) attack.”

Advertisement

Ijeoma Nwosu, who describes herself as a Christian prayer warrior – God’s soldier, insists that every illness, especially mental illnesses, is spiritual despite physical manifestations.

“God is the true healer, who can heal all things,” she says. “He can heal any mental illness, if you humble yourself, repent and come on to him.”

Sometimes though, the healer is a traditional spiritualist.

Like Kolapo Mojeed, the president of the Association of Atorise Traditional and Spiritual Psychiatric Healers of Nigeria.

Advertisement

He seems unassuming until he sits comfortably on one of the wine couches in his living room in Ibadan; and begins to speak of his prowess in healing all types of mental illnesses.

“I can heal all kinds of ‘madness,” he brags.

He blurts out “mad” so easily and so many times, inadvertently fuelling stereotypes that stigmatise people living with mental illnesses.

“There are different types of madness. There is the person who would just refuse to speak. There is the person who would keep laughing uncontrollably. There is the destroyer. There are the violent ones and there are those addicted to drugs,” he continues.

Advertisement

Then Mojeed goes on to explain what he says are the causes of mental illnesses. He categorised them into two major kinds:

The spiritual (where a person is dealing with a mental illness because of a curse, witchcraft) and drug addiction.

Advertisement

“Some people run mad because they offend older people who place a curse on them. Some people run mad because they are money ritualist and used a body part wrongly. Some people run mad because of infighting, so the contender decided to fiddle with his head. Others got addicted to drugs and became mentally ill.”

Advertisement

None of these causes, except– drug addiction, has been medically or scientifically classified as causation of mental illnesses.

As Otefe Edebi, psychiatrist and psychologist, puts it, mental illnesses are neither spiritual nor a defect in character; and there is evidence of a chemical imbalance in the brains of people living with a mental illness.

Advertisement

In general, mental illnesses are caused by a variety of biological, environmental and psychological factors.

The World Health Organisation attributes mental illnesses to social, psychological, and biological factors. The organisation says specific psychological, personality and genetic factors also increase vulnerability to mental health problems.

Mojeed’s descriptions of mental illnesses do not fit WHO’s definition or those of the several mental health experts interviewed for this project.

Worse, his descriptions are not only inaccurate, they are harmful. According to mental health experts, the sort of description he spreads can prevent people with mental illnesses from speaking up or seeking treatment for fear of being stigmatised because of all the negative annotations.

As a result, people living with mental illnesses like psychosis, bipolar, schizophrenia, often show up late for treatment – when the cases are already severe, complicating treatment and reducing chances of recovery, Priscilla Benjamin Olaoye, psychologist and mental health advocate, explains.

This is possibly the reason Mojeed insists that science-based medicine, what he terms “white man’s medicine” is only partly effective.

“You see,” he says. “Mental illnesses caused by drug addiction, money ritual, curses, cannot be fully cured by the ‘white man’s medicine’. It does not work. ”

Mojeed says only a mixture of ogun ibile – traditional medicine, and spiritual can cure mental illnesses fully.

To prove his ability to treat mental illnesses, he takes us to his treatment centre, where Gboyega, a young adult of 25 years old, is shackled and isolated.

Gboyega had been battling an addiction to Indian hemp, so his mental health started to fail. His elder siblings knew only one thing to do -take him to a spiritualist to get ‘healing’. Mojeed, attempting to legitimise his practice and those of the members of his association, insists that the spiritualist’s healing centre Gboyega’s family took him to was fake. He said Gboyega was ill treated and shackled differently from the what should have been.

“They used hard chains that I would not have used,” Mojeed says.

One of Olaiya’s patient with injury caused by shackles from previous mental home

“See the wound on his hands. Those people are frauds and gave him fake treatment so it worsened his condition. The government plans to be arrest people like those.”

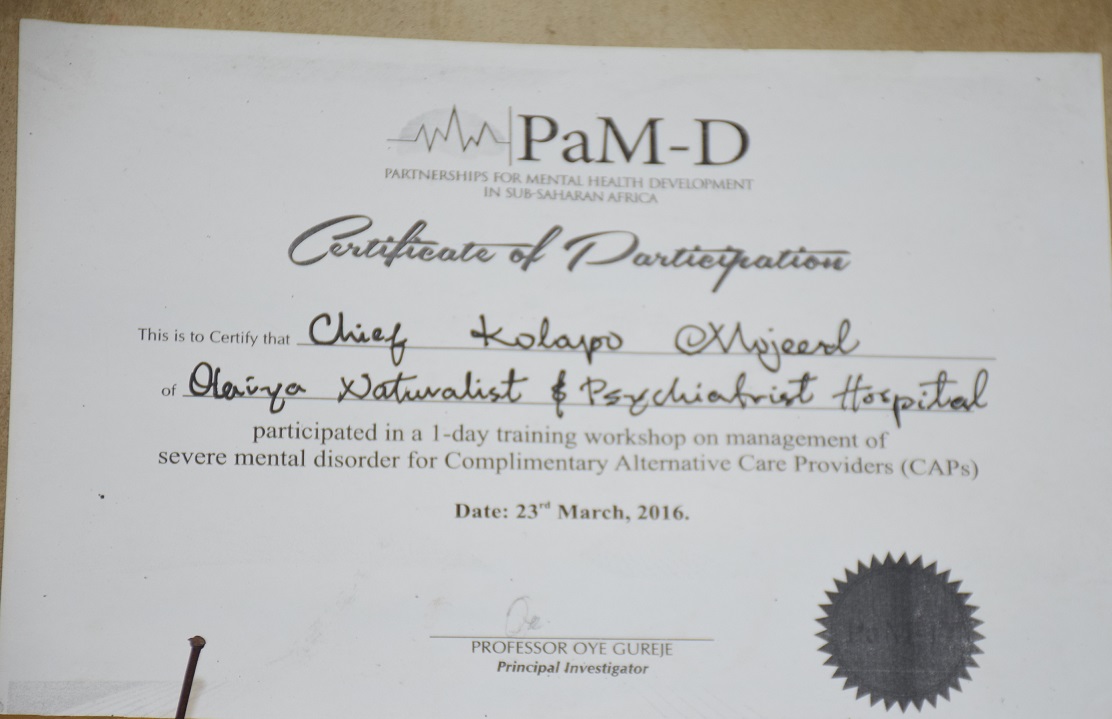

Mojeed boasts about the credibility of his practice. He shows off papers – certificate of attendance of training by the Oyo state ministry of health, and Partnership for Mental Health Development in Sub-Saharan Africa, to validate his practice and his association as authentic.

Then he boasts of the efficacy and uniqueness of his methods.

“I am the first one to surgically operate on the head of the people living with mental illnesses,” Mojeed brags.

“I would shave the person’s hair, apply the medicine on the person’s head, and place cap to cover it. The medicine will then seep through the head pores, heat up the brain and cure the illness.”

Mojeed also administers oral medicine, the kind he describes as potent, making all his clients come back to express profound gratitude, sometimes gifting him houses.

“They are so grateful because no one wants madness in their family. Once I diagnose, I begin the best treatment,” he says.

Mojeed’s system of diagnosis is through divination. He absolutely refuses to show the process. It is a cryptic system that was handed down to him by his beloved grandma who is now late. It was Mojeed the grandma chose to fetch herbs for traditional mixture and eventually give spiritual powers, which he says, never fails to spot a spiritual mental illness. The skills are also useful in spotting drug addicts too.

“Once we see the person, we can tell if the mental illness is caused by witchcraft or curses or by drug addiction.”

After I ask for a diagnosis from Mojeed, he eventually tells me I am an emere – omomi, a water child, who had to be exorcised or risk mental health setbacks and numerous failures including constantly losing money.”

He assures me that hope is not lost and that I could be exorcised.

“We will get your name and then buy the mixture for you. You will the be given a calabash to take to the water, dance around in the midst of a crowd, and then everything will be fine.”

If I wasn’t up for this, Mojeed tells me he could hire people to do it on my behalf. He then gives me a bill of N20,000 for a complete exorcism. Some other people who come to him pay by gestures like buying property and he is not wanting for clients. Even Gboyega will not be treated yet, because as Mojeed says, “his family is not ready financially”. The family is, however, happy for him to be shackled. When they are ready, Mojeed says he will give Gboyega “something that will make him never to return to drugs”.

Why we spiritualise mental illness

Ayomide Adebayo, medical doctor and mental health specialist, explains the reasons Nigerians spiritualise mental illnesses.

A simple explanation, he says, is that Nigerians mostly spiritualise everything.

“For starters, we spiritualise physical illnesses too. So, the question is probably more, why do we spiritualise stuff?” asks Adebayo.

“For one, like most non-Western cultures, we have a sort of dualistic worldview. That means, for good and for ill, we see reality as existing in two dimensions, the spiritual and the physical,” he says.

“Our immersion in spiritualising starts early and goes deep enough that education, at best only teaches us to be more subtle about expressing it.

Adebayo says it is most common for non-western cultures to see spiritual aspects to the most seemingly natural thing.

Addressing spiritualisation of mental illnesses

Adebayo says while he is a Christian and holds on to the Christian worldview, he understands that it does not negate scientific knowledge.

“I say this to highlight a key aspect of the Nigerian way of spiritualisation (which is also identifiable in other non-Western cultures): it sees spiritual and physical as disparate,” he says,

Adebayo insists that it would also be futile to dismiss the belief system of a people in an attempt to convince them of medical options. In trying to persuade people to seek medical options, Adebayo says it is crucial to listen with empathy because entrenched long-lasting culture will not be easily discarded.

“Personally, when religion or spirituality has come up as an obstacle to seeking or accepting medical treatment for someone I’m working with, my goal is to help the person overcome their objections to medical options. Usually this objection arises because their worldview makes medical options seem morally wrong or just useless. So I explain the medical options within the framework of their beliefs so that they all line up. This requires, of course, that I have at least a basic understanding of the major beliefs (which I’ve acquired over time), but even where that’s lacking I can always gain that by simply asking and trying to understand,” he says.

Adebayo says enlisting the influence of religious leaders could be a “game-changer”. This would of course have to be preceded by engagement with them to identify common grounds.

Olugbenga Owoeye, director and head of clinical service, Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital, Yaba, Lagos, agrees with engagement, especially with trado-spiritualists who administer drugs.

“In Nigeria of today, a country of about 200 million people, we have less than 500 psychiatrists,” he says, highlighting the massive shortfall of mental health workers.

Owoeye says it is possible to train the trado-spiritualists and other religious leaders in the basics of mental health so they can assist.

“Once you coordinate them, train them minimally and let them know their limits, they would be able to also assist; because, actually in Nigeria today, the number of mental health professionals are grossly inadequate,” he says.

“The spiritualists already have access to this medication but may not get the right dosage in the preparation. They may not know the biological explanation of what they are treating, but they see their little impact along that line. So, we need to coordinate them to know their limits and refer for more severe cases.”

Project by: Ekeanyanwu and Yemisi Akinbobola

This project was funded by Code for Africa’s impactAfrica programme

Add a comment