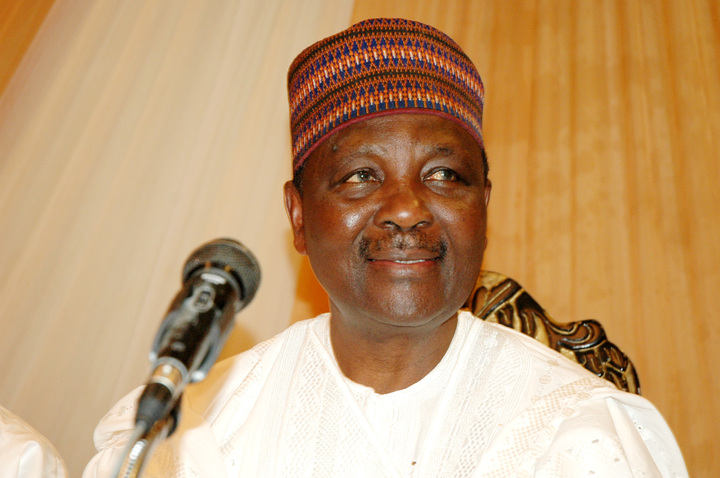

About forty years ago General Yakubu Gowon famously said something about about Nigeria’s problem not being money, ‘but how to spend it’. He uttered those words at a time when the surging price of oil was multiplying federal income faster than sensible spending could catch up with it. (For some context, Nigeria’s oil revenues more than quadrupled in the eight months between September 1973 and May 1974). Those words have haunted Gowon his entire life, but that’s a story for another day. Even though today’s circumstances are very different, I think Gowon’s words are as apt today as they were back then.

Nigeria’s problem is not and has never been a lack of money, but instead a lack of sensibleness regarding spending what’s available to us. I’m fully convinced that the new government can find all of the money it requires to fulfill much of its infrastructure ambitions – but only if it curbs the greediest manifestations of bureaucratic and political appetite, and prioritizes big-impact spending. Between plugging leakages in public finances (TSA), and expanding the tax net (FIRS), and toning down on the indiscriminate award of import and tax waivers, it is possible to swell the federal coffers. Other options include selling stakes in the Joint Ventures (JVs) of the oil and gas industry, bringing transparency to the administration of mining licenses, raising diaspora bonds, and resolving the fuel subsidy conundrum.

With a little bit of imagination we would quickly realise that Nigeria’s biggest problem at this time is not so much having to deal with $40 oil as much as carrying on with a $100 oil mentality – one that allows us focus disproportionately on oil and gas, and that allows the sort of wastage that might be permissible in an oil boom, but definitely suicidal in a bust.

I’d like to focus a bit more on the revenue aspect. On Saturday a Kenyan visitor to Nigeria tweeted that he wasn’t given a receipt for the $50 he paid for an on-arrival visa at the Murtala Mohammed Airport. Mind you the official fee is $25. But apparently not even that official bit gets a receipt issued. It’s shocking that in November 2015, government officials are still choosing to so openly be corrupt, at, of all places, the main entry point into the country. Imagine the extent to which seemingly little, everyday diversions like this robs the country of useful revenues.

Advertisement

Regarding spending the money sensibly (that is, with an eye on large-scale impact), I’ve got a couple of ideas of my own. I’ll look at it from a geopolitical point of view. Let’s start with the South-South. The Niger Delta Amnesty agreement included promises, from the federal government, of an East-West Road (from Warri in Delta State to Oron in Akwa Ibom), and a Coastal Road from Lagos to Calabar. Parts of the East-West Road have been completed, but there’s still some way to go. Those two roads need to be speedily delivered. For the south-east, I’d say the long overdue Second Niger Bridge, as well as a resolution of the contractual issues stalling the operations of Geometric Power’s Integrated Power Plant in Aba.

According to the promoters, they’ve built a 141MW power plant (with a supporting network of gas, transmission and distribution infrastructure) that can serve Aba, one of Nigeria’s most important centers of commerce. But there’s a problem, for the company to start functioning, the government has to resolve ongoing conflict between it and the Enugu Disco. In 2005, long before the 2013 sale of the Disco to its current owners, the Aba IPP says it signed an agreement with the Federal Government, by which the provision of electricity to Aba was concessioned to the company for 20 years, in what is known as a ‘ring-fence’ arrangement. That concession agreement was supposed to be the basis for Geometric Power to go ahead and build its own generation, transmission and distribution system for Aba. Unfortunately, the 2013 sale of Enugu DisCo (whose coverage area includes the area marked out by the Aba ring-fence) appears to have disregarded the existence of the ring-fencing agreement.

For me it’s simple. Whatever the actual situation is, we need to resolve it. If indeed there’s a valid agreement ring-fencing Aba to Geometric, it should be honoured. If there’s a need for a re-negotiation, to find a middle way acceptable to all parties, it should happen as soon as possible. The federal government need to send out a clear message that Nigeria will respect agreements and contracts, and will do everything to ensure that investors enjoy the required attention and levels of transparency.

Advertisement

Imagine what would happen if we managed to supply sufficient electricity to Aba, and turned it into a modern model of industrial activity for the rest of the country. Apart from the obvious economic benefits and environmental benefits of switching away from petrol and diesel generators, there’s also the possibility that the feat might convince naysayers that the APC government is as committed to developing the south-east as the rest of the country. Combined with the second Niger Bridge it might be a powerful argument against those who seek to prove that President Buhari and the APC have no plans for the region.

In the south-west, the Lagos-Ibadan Highway should top the list of priorities. That road has defied three PDP governments; if it defies the APC government we will have to make a formal application to the Guinness Book of World Records, for recognition as the ‘Most Stubborn Failed Road in the World.’ The north-east is a special case. There’s been plenty of talk about a ‘Marshall Plan’ type regeneration programme. There’s already a Presidential Initiative for the North East (PINE), set up by the Jonathan government, and managed from the Office of the National Security Advisor, as a coordinating secretariat for all local and international philanthropic and investment intervention in the region. I haven’t heard a lot about PINE in recent months. But I’ve seen the plan, and it’s impressive.

In the north-west, the Kaduna-Abuja railway line is worth looking at. Most of it has been completed, but for some reason it’s still not running. Also in the northeast, the infrastructure ambitions should focus on building or upgrading dams, especially in Kano, Sokoto and Kaduna, as a three-pronged approach to tackling energy (electricity), environmental (drought and desertification) and agricultural (irrigation) problems in a much-neglected but agriculturally vital region. In the north-central, a network of properly-designed grazing reserves would make sense, as a starting point for bringing lasting peace to a region wracked by land-related violence.

In terms of national impact, three sectors come to mind. First is power. Few things will have greater impact across the entire country than a boost in electricity generation, transmission and distribution. The words of Aliko Dangote from early 2014 keep coming to mind. He told the BBC: ‘Can you imagine that this country has been growing at 7 percent with zero power?’ At the moment we’re generating about 4,000 MW of electricity. Raising this by 30 percent would make an immediately noticeable difference. One thing I took away from a Power Sector Roundtable I recently attended was that there are a number of easy avenues to hitting the current 5,400MW limit of our existing transmission grid. (After that point we’d have to be seriously talking about expanding the TCN’s capacity).

Advertisement

Second, for national impact, are the Kano-Lagos and Port Harcourt-Maiduguri railway lines. The Jonathan government gets the credit for resuscitating much of the national network, several years after it stopped running. But those lines need high-speed upgrades, as soon as possible. Finally, for national impact, is the important matter of housing. I don’t think it’s the work of the new Housing Minister to embark on the construction of housing estates around the country. It might seem like the obvious thing to do, and a project that would be extremely likely to convince people that the government is working. But I think the real work would be in ensuring the implementation of the sort of policies that allow ordinary Nigerians access to the long-term credit needed to build or acquire their own homes. Nigeria does not have a scarcity of individual and institutional property developers; what it lacks are accessible financing models, and the simplicity and transparency of real estate laws and procedures.

All of these suggestions will need to be underpinned by the right legislation. Which is where the National Assembly comes in. The Railway Act of 1955, the Land Use Act of 1978 – these are two of the most important pieces of legislation that need to be revised, to unlock infrastructure potential in this country. Let me just put this out there, just in case you haven’t noticed: I’m extremely optimistic about the immediate and long-term future of Nigeria.

Then again, we’ve been here before – eager and hopeful – haven’t we?

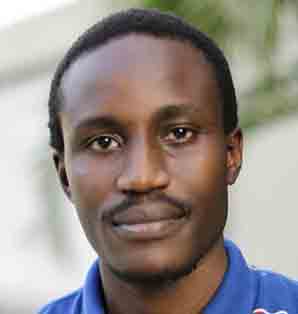

Follow me on Twitter: @toluogunlesi

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment