Ramah Abdullai, holding 3-year-old Rabi who was infected. She’s holding a bottle of the medication giving to her after Rabi was discharged. | Photo: Jesupemi Are/TheCable

She spoke with a wide smile and laughter that burst through unexpectedly at intervals, showing her full set of teeth. “She is the one whose children died of diphtheria,” Hafsat Jaffar’s relative gestured, introducing her. Jaffar’s laughter was so vibrant that one could mistake it for a genuine one, but it was laughter that masked a sorrow so deep that only a grieving mother could understand.

Like millions of people, she started the new year with hopes for what it had in store. Jaffar did not know that her serene life would soon take a tragic turn, and in just a few weeks, a deadly disease made her bury three of her six children.

On the night of February 3, in her semi-completed house located in Dawanau community in Ungogo LGA of Kano state, 30-year-old Jaffar fed her children and put them to sleep. In her usual manner, she also went to bed, hoping to wake up refreshed for the next day.

Jaffar was startled from her peaceful sleep by Khadija, her two-year-old daughter, who climbed the mattress she slept on to complain of a sore throat.

Advertisement

Within minutes, other children of hers, Ahmed, 4, and Khairat, 8, also joined her in bed shouting ‘wayyo Allah (oh Allah)’, pointing at their throats and complaining of fever.

Jaffar immediately began to worry about the situation, especially since Sani, her husband, was away in Yobe state where he worked. Driven by her motherly instinct, she pacified the children and prayed they would feel better soon.

But the next morning, the children were not better, and Khadija, the youngest, seemed to be extremely ill.

Advertisement

Jaffar said it was then that she realised just how serious this strange illness was, and in her confusion, she rushed to Waziri Gidado Hospital to report what was happening.

“They said they would send a doctor and before I got back home, Khadija was unconscious,” she said.

When the doctors arrived, she was told Khadija was dead.

With little time to sit and grieve, her children, including the others who hadn’t made complaints, were taken to Murtala Mohammed Hospital in the state. The health workers told her the children had been infected with diphtheria and would be isolated.

Advertisement

“I realised it was not only me who had children infected with the disease. We were three in number who had isolated children,” Jaffar said.

The young woman, with a look of resignation on her face, said Ahmed died a few days later, and Khairat followed not long after.

Pointing at Dawanau Psychiatric Hospital, in whose compound her house is situated, she said in December, a few months before the tragedy, a doctor had advised her to get her children vaccinated. She was told one of the vaccinations included diphtheria.

“The doctor told me about the diphtheria outbreak, and they assured us that after the vaccination we were safe from the outbreak, and I agreed,” she said. “But after that, the children did not take another dose.”

Advertisement

Now heavily pregnant with a radiating smile, Jaffar said she felt so much pain from losing three children in such a short time.

“After the children died, my husband came home. But he was not around when the children were buried. They were buried by their grandparents,” she said.

Advertisement

“Another painful thing was that when my neighbours witnessed the death of my children from this disease, they stopped associating with me.

“The rest of my children were also not happy, and they couldn’t stay in the house anymore; they left for their grandparents’ house.”

Advertisement

As for Ramah Abdullai, a resident of the Tudum Fulanin community in Ungogo LGA, her three-year-old daughter, Rabi, started developing symptoms of diphtheria in the wee hours of August 2.

“She woke up crying. I was petting her, but she kept crying and running a temperature till around 5 a.m. before she was able to have a deep sleep,” Abdullai said.

Advertisement

Relieved, the mother of five began to cook and do other house chores. She then asked one of her daughters to wake Rabi up so that she could have breakfast and then visit a pharmacy nearby.

The next thing she heard was a scream from inside.

“My daughter, whom I sent to carry her, shouted, ‘Umma (my mother), Rabi’s neck has swollen up’. I rushed to meet her, and I saw that her neck was really swollen. I called my husband’s elder brother and he said we should go to the hospital,” Abdullai recounted.

“I took her to Mongoro PHC in the morning around 9 a.m., but doctors were not around. After some minutes, the doctors arrived.

“The doctor examined her and said an ambulance would take us to the hospital. We were given facemasks and I was taken to Zaana Hospital around 10 a.m. In the hospital, an isolation centre, where Diphtheria patients would be kept, was set up.”

Rabi was confirmed to be infected with diphtheria and was admitted for three days to the new isolation ward.

“I was scared. I cried when I was informed that my child had diphtheria because I heard of children who died from the disease. I wasn’t okay till my daughter was fine and discharged,” she said.

Before Rabi contracted diphtheria, she had only received the polio vaccine and that was the only time the child ever received any jab.

Abdullahi admitted that she was negligent with vaccinations for her children but insisted it was not entirely her fault.

“No one explained to me how frequently I should bring my children for vaccinations or the types of vaccines they are to receive,” she said.

“When the diphtheria vaccination started, it was administered at the residence of our community leader; but before the news reached me, they said the vaccination had finished.

“They used a selective process in the diphtheria vaccination. In some households, only two or three children were vaccinated, while the rest were not. In my house, none of my children were selected.”

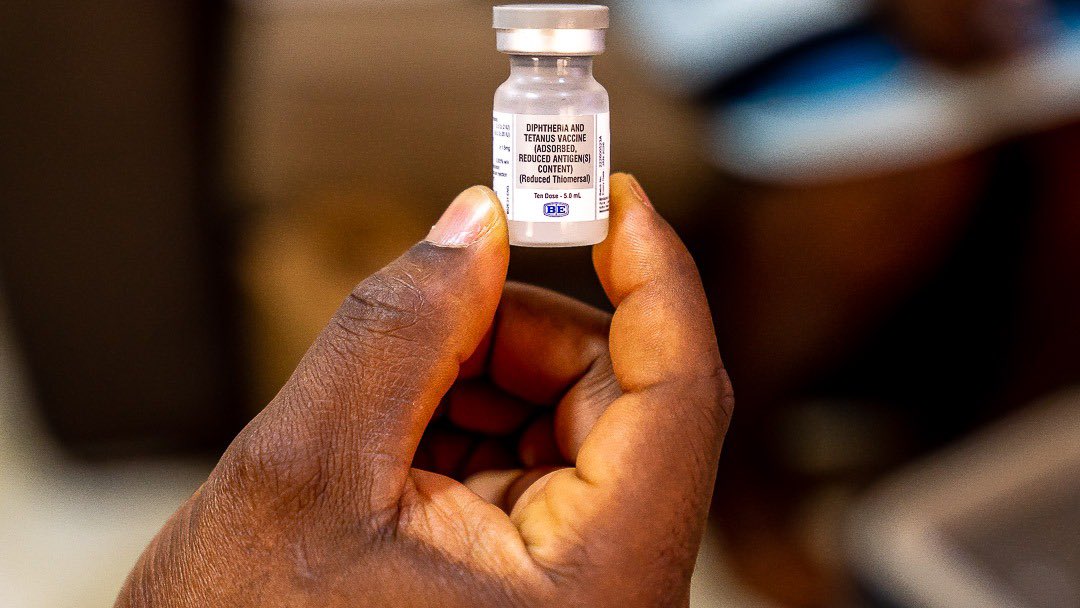

DIPHTHERIA OUTBREAK IN NIGERIA

Diphtheria is a bacterial infection caused by corynebacterium diphtheriae, which is transmitted through close contact with infected individuals through respiratory secretions like coughing, sneezing, or talking. The disease primarily affects the nose, throat, and airways, causing breathing difficulties, fever, and the formation of a thick coating in the throat.

In Nigeria, diphtheria has been a long-standing concern for public health and has a record of outbreaks in the past.

For instance, twelve years ago, between February and November 2011, a diphtheria outbreak was reported in Kimba village and some surrounding settlements in Borno. Throughout the outbreak, a total of 98 cases were reported, out of which 21 died.

At the time, the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) attributed the outbreak and the high fatality rate to low vaccination coverage and delays in diagnosis.

In December 2022, the NCDC was informed of suspected diphtheria outbreaks in Kano and Lagos states, and that was the start of the current outbreak the country is grappling with.

As of October 18, 2023, there have been 15,060 reported suspected cases, out of which 8,406 were confirmed from 136 LGAs in 20 states, including the FCT. Kano – 7,747 (81.7%), Yobe – 841, Bauchi – 369, have recorded the highest number of cases so far.

Over 400 people have died from this vaccine-preventable disease.

To curtail the infection, the Nigerian childhood immunisation schedule recommends three doses of pentavalent vaccine (diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine).

It is recommended that the first dose be taken at six weeks of age, the second dose at 10 weeks of age, and the third dose at 14 weeks of age.

On the other hand, TD (tetanus and diphtheria) is also recommended for children seven years of age and older, adolescents, and adults.

However, the federal government has said on several occasions that most of the confirmed cases of diphtheria in the country were unvaccinated against the disease.

“A historical gap in vaccination coverage is a driver of the outbreak, given the most affected age group and the results of the nationwide diphtheria immunity survey that show only 42% of children under 15 years old are fully protected from diphtheria,” the NCDC said in a statement.

Speaking with the media recently, Faisal Shuaib, executive director of the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA), said over 80 per cent of children who contracted diphtheria never received routine vaccinations.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), Nigeria has low national coverage of the pentavalent vaccine (Penta 3) administered in routine immunisation, and suboptimal vaccination coverage in the pediatric population, with 43 per cent of the target population unvaccinated.

LOW AWARENESS

According to a study focused on zero or missed dose vaccinations in Nigeria, one of the factors responsible for low vaccination coverage in Nigeria is low awareness of the need for vaccines by parents and caregivers.

When two of Abdullahi Kabir’s children — three-year-old Hasia and 17-year-old Hawawu – started complaining of blocked throats and breathing difficulties, he was confused and decided to take them to Mongoro PHC.

But even at the health centre, Hasia, who was in worse condition, was not responding to treatment. This prompted his decision to take his children to Murtala Mohammed Hospital, where they were confirmed to be infected with diphtheria.

Unfortunately, Hasia died not long after their arrival at the hospital, and Hawawu began receiving treatment.

The resident of Tudum Fulanin in Kano said his children had not been vaccinated before the outbreak because he was not aware of the need. But after Hasia’s death and some sensitisation in the community, he took his remaining 15 children to get all the necessary vaccinations.

“All my children have now been vaccinated, including Hawawu who survived. If it were my own will, Hasia would not have died, but it has already happened,” he said.

“It is something the almighty has already written, so I have no choice but to accept it.”

Abdulrahman Nasir, who is also a resident of Tudum Fulanin, when three of his children started complaining of sore throats, his first response was to visit a pharmacy and buy them malaria medication.

But after taking the medication for a few days, four-year-old Aliyu, six-year-old Khadija and seven-year-old Usman were not better. This led the concerned father to visit the health centre, where he was told his children were suffering from diphtheria.

Thankfully, all the children survived.

Nasir said before the outbreak that his children had, on one occasion, received one vaccine he believed to be for polio.

“I was not aware that there were more vaccines after that. It was after my three children got infected with diphtheria that they got the vaccine at the health centre,” he said.

“I have gone to PHC to tell the workers to come and vaccinate my other children, but they have not come.

The last time I went there, they said it was not available. I don’t want the other 15 children to get the disease.”

‘VACCINES NOT AVAILABLE AT HEALTH CENTRES’

Saifullahi Bello, the health worker in charge of Tudum Fulani PHC in Ungongo LGA, claimed the health centre had been vaccinating children against diphtheria prior to the outbreak, “but sometimes the vaccine is not available”.

“Normally, at 6 weeks, 10 weeks, and 14 weeks of childhood, there is a penta vaccine that is provided to the children on the expanded program of immunisation schedule,” he said.

“The Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) is running a training on outreach services. Whenever the vaccine is not available, it is through the outreach that we get the vaccine, while some have to go to Murtala Muhammed Hospital.”

The health worker said other contributors to the outbreak include the non-completion of medication after discharge and the refusal of parents to come back for other doses of the vaccine.

“For some, the far distance to the health facility is a challenge, while some people have just refused to bring their children for vaccinations. They mostly come out when there is an outbreak,” he said.

On the other hand, Saidat Kabiru, a health worker at Adakawa PHC in Dala LGA, said before the outbreak, the centre was not administering the pentavalent or TD vaccine.

Kabiru said initially, campaigns were carried out to sensitise residents, but even then, the vaccines were not available at the health centre. The vaccines, according to the health worker, only arrived a few months after the outbreak.

“We currently have the vaccine. We administered the first dose in the past month, and now we are administering the second round. But we need more because sometimes we run out of the vaccine, and we refer people to Murtala Mohammed Hospital,” Kabiru said

Usaini Sanni, a member of the World Development Committee working at Kantudu PHC in Dala LGA of Kano, said before the outbreak, the vaccines were not available in the centre.

“Even when the outbreak was serious, the vaccine was not available. One had to go to Murtala Mohammed Hospital to get vaccinated. It was just five days back that they got the vaccination,” he said.

“They have been vaccinating children for other diseases like polio, but they didn’t have the doses for diphtheria.”

‘SUPPLY, DEMAND ISSUES CAUSED VACCINATION GAPS’

Speaking recently at a press briefing, Ifedayo Adetifa, director-general of the NCDC, said five to 14-year-olds are bearing the brunt of the outbreak, adding that this shows most of the vaccination gaps occurred from 2009 to 2018.

On what caused the gaps during this period, Faisal Shuaib, the NPHCDA executive director, said supply and demand issues were responsible.

He said on the demand side, parents do not take their children for vaccination for multiple reasons.

“The lack of awareness is one of the reasons. Many parents are not aware that these vaccines are important to protect against these vaccine-preventable diseases. It is an issue of a lack of information and knowledge about vaccines,” Shuaib said.

“This is why, as an agency, we have stepped up to create this awareness and also make sure we address the issues around supply.”

On the supply side, he said there are issues surrounding the availability of health services and missed opportunities.

“For example, a woman can deliver in the hospital, and instead of starting vaccinations immediately after delivery, the health workers may say the vaccine will be administered on the mother’s next visit. But that visit may never come,” the NPHCDA executive director said.

Shuaib added that in some instances, there were “stock-outs of those vaccines” in those years. However, he claimed that this is no longer happening.

“There are also issues around hesitancy and suspicion that vaccines are not as potent as they should be. This is why we have been working with community and religious leaders over the years to educate their community members,” he noted.

“When a survey was done in 2016, diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine (DPT) coverage was around 33 per cent but it increased to up to 71 per cent in 2019. But because of the pandemic, it has now come down to 57 per cent.

“There has been some improvement in the last five years, but we are not there yet,” Shuaib added.

Due to the outbreak, the NPHCDA embarked on a mass vaccination exercise, improved surveillance of the disease, began airing jingles on the radio to sensitise the public, and began engaging with school authorities.

But what happens when the outbreak ends? The contribution that poor awareness and a vaccine shortage have made to diphtheria vaccination gaps in Nigeria shows that the government needs to review existing and regular vaccination plans to ensure every child is reached at the appropriate time.

Add a comment