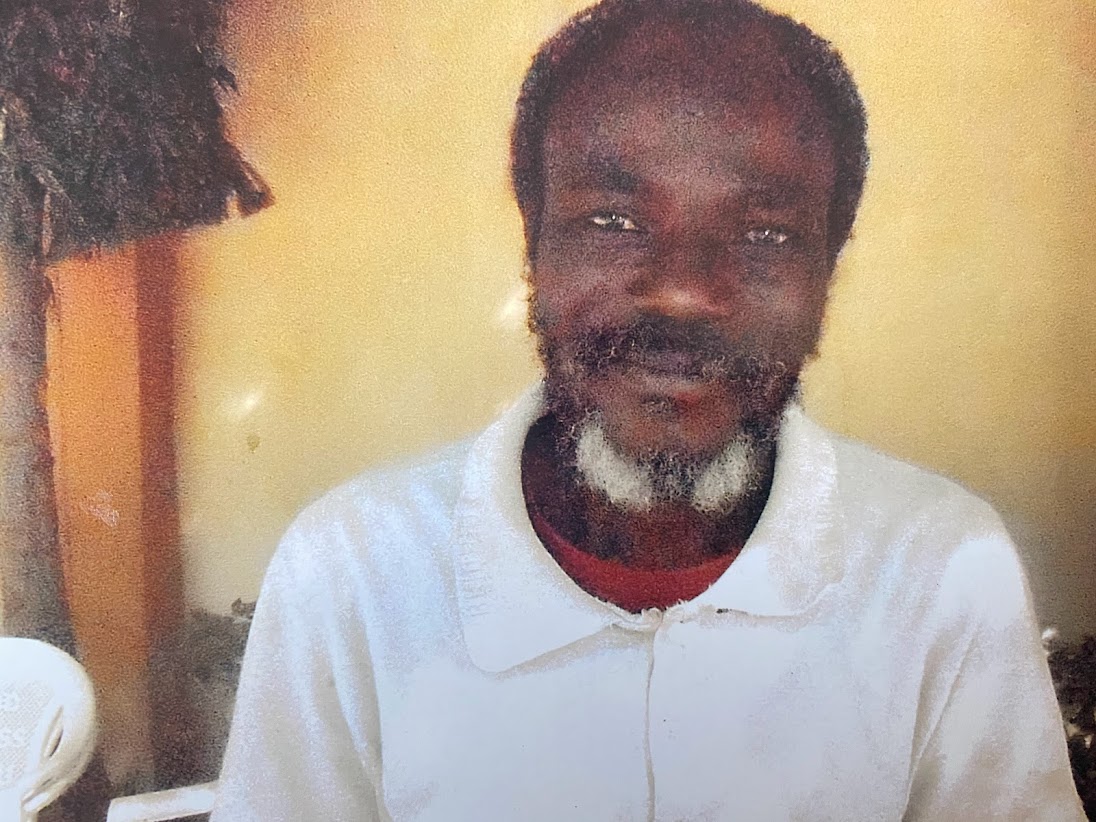

Since 2014, when over 200 schoolgirls were abducted by Boko Haram insurgents in Chibok, many have remained wary of the southern Borno town. But that didn’t scare Moses Oyeleke, a pastor with the Living Faith Church who had served in Chibok. Born and raised in Borno, Oyeleke knows the southern Borno axis like the back of his hand. He speaks Hausa and Kanuri fluently, camouflaging his Osun roots to blend in with the locals. Perhaps, that was what saved him during his frequent and brief encounters with the Boko Haram insurgents whenever he explored the area on his motorcycle. But none of that mattered when the pastor’s luck ran out and sent him to seven months of captivity with the terrorists.

On April 10, 2019, Oyeleke set out from Maiduguri, on a directive from his church’s headquarters to deliver relief materials to internally displaced persons (IDPs) camped in Chibok. A few kilometres from Bama LGA was a military checkpoint in Yale, a small village. Moving with two trucks – one filled with grains for the IDPs and the other occupied by him, a corps member identified as Abraham Amutu and the driver – was enough to raise brows from the soldiers on guard. But the armed soldiers were not the only ones curious about what he was carrying. A number of Boko Haram insurgents who were already on treetops “just 200 metres ahead” also had their interest piqued. He later knew this from the group’s leader who he came to know as “commander small”. After a satisfactory check by the military, Oyeleke and his co-sojourners continued their journey but their trip was cut short by the insurgents already swinging from the trees, waiting to waylay the trio.

“It was the driver that first saw them, they were high up on the tree,” Oyeleke tells TheCable. “So, they were able to see people coming and everything that was happening at the military checkpoint. They told me that when a vehicle is coming and they notice it stayed at the checkpoint for a long time, they understood that the vehicle had valuables. But people don’t know that because while we were there, other vehicles were passing freely because they did not have as much load as us.

“We had not gone far after the checkpoint before the Boko Haram attacked us. The first thing we heard was gunshots. They shot at our tyres and brought our trucks to a halt.”

Advertisement

The grain truck driver escaped but at the will of the terrorists. The reason, Oyeleke said the terrorists told him, was to “tell people what he had seen” — to spread the terror.

Afterwards, he and the corps member embarked on a “four-hour walk” to the terrorists’ base while the other driver was instructed to drive the food truck. It wasn’t quite a distance, he recalled, before they began to hear gunshots from the soldiers who were just a few meters from the scene of the attack. But they were already in the thick of the forest and the terrorists knew the area better – that was how they managed to stay out of the soldiers’ radar.

“While we were walking, we were meeting other villagers in the Boko Haram settlements. They would see us and shout ‘Allahu Akbar, happy that we were arrested. Sometimes they would give us water, sometimes they would allow us rest,” he recounted.

Advertisement

Combining a “normal” life with activities of crime is a routine for the terrorists, Oyeleke discovered. They own bakeries and go to small markets in the village to do business. There are families and there are the combatants regarded as soldiers. Slinging a gun across their torsos with a hoe in hand to till the ground was not something Oyeleke could reconcile. That was the reason he couldn’t eat his first meal of “rice and beans and chicken” offered on his first night with the insurgents.

“I remember it vividly. They offered us food – rice and beans and chicken – but I couldn’t eat it. Maybe it was the fear in me, I don’t know. They told me in Hausa that there was nothing in it and that I should eat, so I just took a spoon so as not to anger them. Even after they showed us where we would sleep for the night, I couldn’t sleep,” he said.

It was the crippling fear Oyeleke had that made him hide his identity as a pastor the following day when he was questioned. He had heard of how Christians, especially the leaders, suffered gruesome deaths at the hands of the terrorists and he did not want the same fate. His new identity was an onion farmer on his way to Gwoza to check his farms.

Later that evening, sandwiched between two heavily armed Boko Haram fighters, and a fleet of motorbikes as escorts, Oyeleke began his sojourn into Sambisa forest, the hideout of Abubakar Shekau, the leader of the group until his demise. The forest, to the extremists, is referred to as Dar al-Islam, a dominion of Islam. To them, it is a country, and Oyeleke and his fellow captives would stay in Irasa, one of the “states”.

Advertisement

The journey from Bama to the forest took over a day, mostly because they travelled at night to cover their tracks.

The uncertainty of his fate intensified when “six well-kitted soldiers, smartly dressed like our Nigerian army, with only the turbans on their heads as a distinction, arrived on bikes” and inspected them, announcing that they would take him to Shekau. In between their intra-Sambisa trips, Oyeleke recalls being served, again, with “rice and beans and chicken” for dinner.

‘REVEALING MY IDENTITY AS A PASTOR’

To make demands in exchange for hostages, terrorists would often make videos as proof of life of their victims. It was during one of such instances that Oyeleke suddenly felt emboldened to reveal his identity as a pastor.

Advertisement

“It was a voice in my head that asked me to do it,” he said. According to him, the revelation made his captors halt the recording abruptly, asking him why he did not reveal that information beforehand.

He told them he had heard “what they do when they catch pastors” and that was why he claimed to be a farmer, but he had decided to “come clean”. If Oyeleke had known that the revelation would elevate his status among the terrorists, he would have confessed earlier.

Advertisement

“From that day to the day I left, it was a different kind of treatment from them. They started seeing me in a new light and even started calling me ‘Baba Pastor’. Although they probably didn’t want me to notice immediately because they said they would keep me with them until their religion tells them what to do with me. That created another level of fear,” the pastor said.

Upon learning of his new identity, they took him to where he would “sleep, wake up, eat, and not shave his beard” for the next seven months. Oyeleke said the houses occupied by the terrorists were made of zinc sheets, mud, and straw.

Advertisement

Occasionally, they would take him around the forest to look for network so they could place calls to his church, negotiating for an initial demand of N200 million.

MEETING ‘COMMANDER HAMZA,’ A GRADUATE AND ENGLISH TRANSLATOR

Advertisement

Oyeleke is sure he was able to cope with the situation because of the relationships he fostered with the sect’s members. One of which was a “friendship” with one of the leaders, a man he identified as “Commander Hamza”.

“We developed relationships when I was already three months old there,” he said. “They are normal human beings who have changed because of the kind of work they do. There was a particular one among them that I felt was a God-sent angel to me. His name is Commander Hamza. After negotiations were unsuccessful, he would come and tell me in Hausa not to worry, that he would tell them what to do.

“I told him I was a Yoruba man and I married a woman from southern Borno. Coincidentally, that was where he was from too. That was how he picked interest in me.”

Oyeleke almost found it strange that Hamza had a university education and had a moderate grasp of the English language. The pastor’s curiosity made him discover a few other fighters, just like Hamza, who were also graduates. He would always wonder what could have pushed a graduate to settle in a dreaded forest, and make a living from insurgency.

“Hamza is educated and he’s the one that they take along as an English translator sometimes. I found some of them are graduates,” Oyeleke said.

Whenever he was depressed, he would send for Hamza and “he would comfort me,” saying he was working on getting him out.

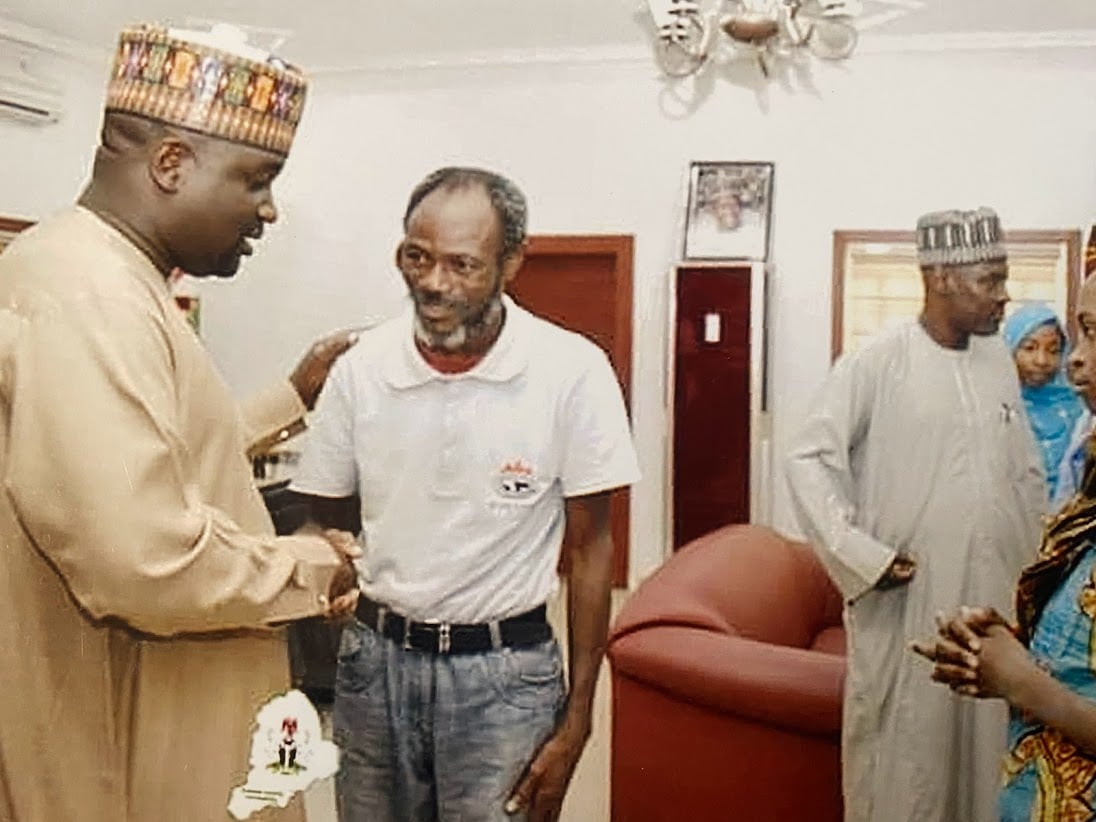

OYELEKE’S RELEASE

His captors had promised him freedom but that promise had taken three months and Oyeleke was losing hope. Eventually, he fell sick. But treatment with “high quality imported” drugs and blood capsules quickly sprung him to his feet.

Around 1 am on November 10, 2019, the seventh month of his abduction, Oyeleke, alongside a 14-year-old girl leaving her sister behind, was woken up to “get on the bike with the terrorists and leave”.

The six-hour bike ride to the ransom exchange venue was greeted with a ceremonial meal of “rice and beans” but this time, without chicken.

Oyeleke said they waited for about nine hours before members of the Katung Foundation, an organisation that facilitated their freedom, came for their release at a place he describes as a “highway leading to Gwoza”. They were tucked away in the bush at an angle where civilians could not see from the road, but they had an eagle-eye view.

“It was not a small move from the forest to where we were released. There were high-grade Hilux trucks with about 50 heavily armed men escorting us. Unknown to the people who came to collect us, Boko Haram had already surrounded them in case they wanted to come with soldiers. Luckily for them and us the captives, they came alone,” he said.

Amutu, the corps member, according to the Boko Haram insurgents, chose to stay behind. For him, he had found “a new path”. His new path would, however, be closed off in combat with the ISWAP fighters, leaving behind two wives that he had taken in the forest.

Upon his release, many had expected Oyeleke to be transferred out of the north-east. Some of his kinsmen down south had thought he would move his family out of the north, but nowhere would feel like home to the pastor who now spends most of his time at the church’s bookshop in Maiduguri, the Borno state capital.

“One thing I am always grateful for is the gift of life. This is what matters most. Would I be able to ask for anything if I had died?” he said.

As the insurgents still terrorise some parts of Borno, Oyeleke and his family, recently, almost fell victim again. It was on their way back to Maiduguri from a funeral in southern Borno. But this time, the army was successful in repelling the terrorists.

Although he said his wife and daughter were terrified, he was able to pull them together.

Add a comment