When a group of heavily armed men invaded communities in Niger, many residents were forced to flee to Central Primary School, Gwada — a town in Shiroro LGA of the state.

Azumi Markus is one of them — she once lived in Sabon Kabila in Munya LGA before she was pressured out of the village by the relentless terror of bandits.

The mother of two could not remember her exact age but looked quite young. As she rested her frail frame on a brick pillar, she seemed perturbed while watching a group of children devour a bowl of mashed tuwon masara – a food made from maize.

Advertisement

Azumi escaped to the IDP camp with two children but is now left with only one child. After the attack on her village, she had to seek refuge in the bush for over one month.

“After the thieves (bandits) invaded, we waited till night and ran into the bush, we stayed in the bush for over one month with nothing above our heads except trees,” she recounted.

“I had my two children with me, the last boy was just about six months old, he seemed very healthy when we arrived at the IDP camp but fell very sick after some weeks and died.”

Advertisement

Azumi said when the infant suddenly expelled watery stool and started to throw up, she thought it was the usual discomfort that occurs during teeth development.

“He was taken to a clinic in Chibiani village, we bought all the medicines we were asked to buy but the vomiting and defecation did not stop. He died and left all the drugs,” she lamented.

CHOLERA IN IDP CAMP

Advertisement

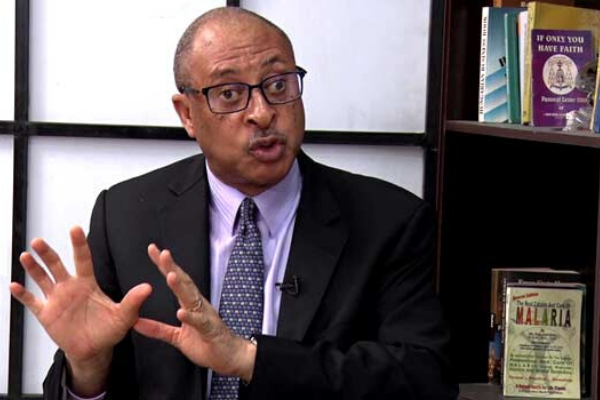

Habibu Kurebe, one of the officials in charge of Gwada IDP camp, said three children were lost to cholera between October and November 2021. He explained that the camp has no medical capacity to handle such cases.

“Two months ago, we had a cholera outbreak here in the IDP camp. We lost about three children to the disease. The IDPs really tried because some of them had to rush the children to hospitals in the town, and thankfully some children were saved,” he said.

“The parents of the children told us that they complained of stomach pains and suddenly started running temperature. This was soon followed by vomiting and defecating loose, watery stools. It was so sudden that we could not even do anything, most of the medicines donated are not usually enough to treat even malaria cases.”

UNHYGIENIC CONDITIONS

Advertisement

He said the hygiene level in the camp is a serious source of concern as IDPs often leave their food and water containers uncovered and expose themselves to unsanitary conditions due to lack of awareness.

“If only we can have experts from NGOs or other health organisations that can come here and educate them on the need to sustain proper hygiene because they have no idea how to keep their environment healthy,” he said.

Advertisement

Speaking on food availability, Kurebe said the IDPs only eat once a day and hardly enjoy a balanced diet, as they mostly feed on the local dami-dami – mashed food made from maize or millet.

“The bigger challenge is food, there is not enough food to go round, whenever some organisations bring food, it doesn’t last long because of the population,” he said.

Advertisement

‘I THOUGHT IT WAS MALARIA’

Advertisement

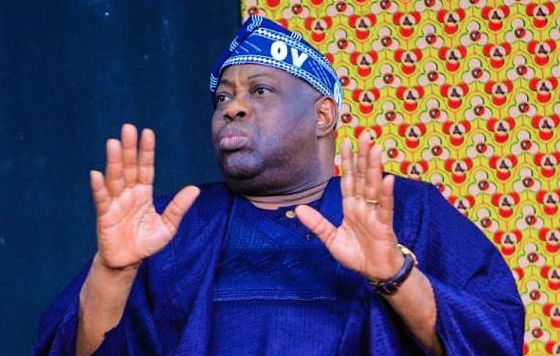

Tani Hassan, 37, had just returned from the market when she noticed that she was running a temperature.

Her eyes were hot and her throat parched, so she went to the mud-made container to fetch water to drink.

“I thought it was normal malaria, so I went to drink water with plans to cook but started experiencing body weakness and suddenly had profuse watery diarrhoea. While I was still dealing with that, the diarrhoea came with unbearable abdominal pain. The cramp was like a fire eruption in my stomach,” she recounted.

She battled cholera for two days without seeking medical attention, choosing to use anti-malaria and painkiller drugs.

Tani, a mother of five children who escaped from Kaure in 2019 to resettle in the IDP camp, eventually required treatment at the hospital.

“I opened my eyes and saw myself at the hospital, I didn’t know how I got there but I was told my husband rushed me to the clinic in Tawali— a village near Gwada town,” she said.

“I was given nothing less than 20 drips before I regained my health. After I was discharged from the clinic, I couldn’t walk properly, the pain from the diarrhoea was still fresh in my anus.”

Tani said the camp recorded over ten cases, mostly women, confirming that three toddlers between the ages of three and five died during the outbreak.

When she returned from the clinic, Tani said she started to wash her clothes daily and ensured that she bathed regularly.

But her newfound hygienic practices did not extend to the food she ingests.

Responding to why she often leaves food uncovered, she said it was to prevent them from getting spoilt.

“We don’t usually have enough food to eat, do you want us to cover them so that they will get spoilt?” she asked.

DRIVERS OF DISEASE IN IDP CAMPS

By virtue of their living conditions, many IPDS in various camps are susceptible to cholera, which is caused by factors such as population congestion, open defecation, poor sewage system, poor sanitation and lack of clean water supply.

While in Gwanda, TheCable observed that foods undergoing processing were left uncovered with flies feasting on them, and worse still, unhygienic pots were used to prepare meals and food remnants were disposed of close to cooking areas.

These practices expose IDPs to food and waterborne disease as most camps, formerly government-owned schools, do not have adequate supply of clean water — a situation that makes open defecation a regular occurrence.

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 26.5 million children do not have access to enough water to meet their daily needs in Nigeria.

Although about 70 percent of Nigerians have access to water services, over half of the water sources are polluted and only nine litres of water on average is available to a Nigerian daily.

HOW TO CONTAIN CHOLERA IN IDP CAMPS

Although cholera is deadly, it can be contained where adequate access to water supply, hygiene and sanitary facilities are available.

Many IDPs are rural dwellers who have not undergone proper education to understand the gravity of unclean environment and exposed foods.

The sustainable development goal (SDG) 6 targets access to clean water and proper sanitation. The objective can be achieved when diseases transmitted through unhealthy human activities, such as poor sanitation, open defecation, and poor management of waste, are addressed.

Cholera can be curtailed through the integration of water resources management into communities, protection of water resources and water-related ecosystem, provision of capacity-building assistance to communities to develop water and sanitation-related activities and organising programmes on desalination, water efficiency, wastewater treatment, as well as tackling open defecation.