“Everything she does is magic” is a hashtag created by one mum, Chizoba Peters, for her child who is on the autism spectrum.

On this Saturday afternoon, the blistering sun rays connived with Lagos humidity to drive most people under a shade, but Peters would not budge. She had just finished an intensive Zumba workout session with the sole aim of raising funds and awareness for autism.

She would still oblige TheCable this interview because she was keen on raising awareness on autism and deconstructing misconceptions.

“I want to take this as far as it can go, to make it a staple. We need autism training and it is based on the fundamentals that you need to help the child on the spectrum and in Nigeria, this is hard. There is no one to give you a list of certified speech therapist or a certified occupational therapist so it is hard to evaluate what you are doing with your child,” she says.

Advertisement

With her face fraught with worry over the lack of access to the management and treatment of autism and the ignorance and stigma that bedevils autism in Nigeria, Peters recalls low moments when a teacher in her daughter’s school discriminated against her child and acted unprofessionally.

Like the time when a teacher told her daughter to stay away from another child because she didn’t want the child “acting like her” or the time another teacher isolated her, put her in a separate room from other kids in school with no one to tend to her.

“Autism in not contagious,” she says with a look of unbelief at the ridiculosity of the pervasive stereotype of autism in Nigeria.

Advertisement

“It’s not contagious! What does that even mean? a neurotypical child is a neurotypical child,” Peters said explaining that a child without autism cannot suddenly become autistic by being around another child with autism.

She explains that children on the autism spectrum just process information around them differently from neurotypical children and, therefore, cannot possibly transfer their understanding of stimuli to another child.

And with Peter’s magical child, it is sensitivity to sound and touch among the other manifestations.

“With my daughter, there are sounds that seem like normal to you, but she’s covering her ears.

Advertisement

“She processes stimulus differently and sometimes she doesn’t want you to touch her or she doesn’t want to maintain eye contact,” Peters said.

“I have read a book about someone who is on the spectrum, who was explaining something and he said sometimes he’s looking at your face and it looks like he’s looking at fifty pictures at the same time that’s why they avoid eye contact because it is too much information,” she explained.

Autism is really just a variety of behavioural manifestations that can occur with or without intellectual and language disability.

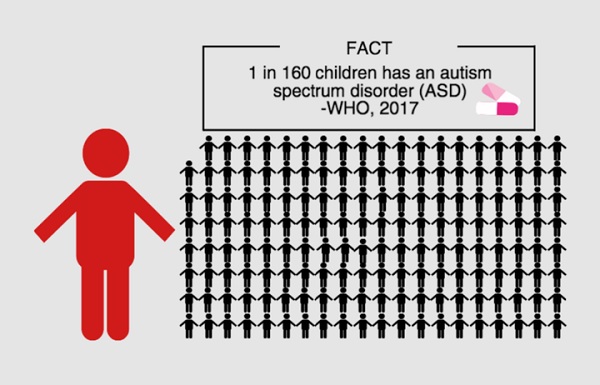

According to the World Health Organisation, Autism spectrum disorders is a group of complex “developmental disorders and conditions that emerge in early childhood and, in most cases, persist throughout the lifespan and are marked by the presence of impaired development in social interaction and communication and a restricted repertoire of activity and interest, with or without accompanying intellectual and language disabilities; and that manifestations of the disorder vary greatly in terms of combinations and levels of severity of symptoms.”

Advertisement

Ranti Oguntayo, a special needs interventionist, told this reporter that in Nigeria, kids with autism and other special needs are demonised because of a lack of understanding.

“People don’t understand what we are dealing with. Parents are still scared of what people will say. There are few people who are knowledgeable about autism and so very few people who can give you constructive advice.”

Advertisement

Oguntayo said she witnesses a lot of parents “who are even educated” hide their children on the spectrum.

“They are embarrassed and keep these children in hiding because of the stigma associated with autism. It is a lot of ignorance,” she says adding that children with autism have absolutely nothing wrong with them and are just neuro-diverse.

Advertisement

“We do not truly grasp the population of people living with autism,” she says.

“In almost every centre that works with children with a learning disability that I have consulted for, 30 out of 34 children are on the spectrum,” she said.

Advertisement

Last year, Oguntayo told this reporter a story of a young autistic child who beaten severely by the father, a pastor of the Mountain of Fire and Miracles church.

“The boy was beaten to a pulp. I saw terrible injuries on his back and his dad, a pastor in the Mountain of Fire and Miracles church, said ‘if I can deliver other people, why can’t I deliver my son,” Oguntayo said as she added that there is a pervasive “ignorant” narrative that autism is spiritual.

Autism is, however, not a spiritual issue. It is a learning disability that affects the way the brain processes information.

As Peters explained, “Children on the spectrum are not imitators like neurotypical children.”

“They have to be taught everything. While neurotypical children can learn through play, it is really not the same for children on the spectrum,” Peters said.

And because children on the spectrum have different coping mechanisms and are often hyperactive, they are often regarded as difficult by people who are not autism aware.

Peters said this is one of the reasons she forgave the teachers who discriminated against her child easily – because they did not know any better.

“People don’t know what autism is. It affects social interactions, yes, but there is nothing wrong with an autistic child.

“There are autistic children that are geniuses,” she says.

Dotun Akande, a mother of a child who was diagnosed with autism in 2000, agrees with Peters.

Akande’s son is now a math genius, always topping his class in subjects like physics and math and now studying mathematics at the university.

She told TheCable of the excruciating experience that was the birth of her child culminating in a near 24-hour labour that birthed a boy who met all his milestones – sat at the right time, walked at the right time and said his first word – daddy – at the right time.

But at 18 months, she noticed a retrogression.

“I noticed that about 18 months, he stopped talking and replaced it with sucking. At about 24 months, there were no words at all and I was worried.

“So I took him to the hospital and they said to me – Mrs Akande, don’t worry, he is a boy, boys talk late.”

Akande said since she had a child before her son on the autism spectrum, it was hard for her to accept the explanations of “boys talk late”.

Her son would pace up and down before her if he wanted something and would just not speak to her.

When he turned a little over two years, she saw a paediatrician who told her that her son had autism.

The paediatrician said to me “Dotun, I think your son has autism”.

In 2000, this was a miraculous diagnosis that only happened because the paediatrician had a similar experience with her soon.

“In 2000, not a lot of people knew what autism was and we won’t have been able to detect. So, she (the paediatrician) said to me, there is nothing available in Nigeria if you must do anything, you have to take him to the United Kingdom or the US.”

Akande and her family had a good life in Nigeria and had no plans to relocate.

The next best thing for her was to get a speech therapist (introduced by the paediatrician) and to do with some autism management tips she got from the paediatrician.

“After school, get him out of class,” Akande said the paediatrician told her “Tell the teacher to do one hour (extra tutoring) of whatever it was they did in school, and generally just watch him as you go.”

The tips, simplistic as they seemed, did two things, unlocked the potential of a little boy who fell in love with music and became a math genius with a keen sense of detail; and ultimately, birthed the Patrick Speech and Language centre – the first autism centre in Nigeria.

At first, the gains of adhering to the tips were slow but sure.

“We got a speech therapist to come in for two or three days a week of speech therapy and a teacher to come in every day after school.

“And for two years, we saw very little improvement and he would say just one, he would say ‘ cup, drink, take’. At a particular period, I was really worried. I had prayed and fasted and done everything a mother should do, so why should it be my son that would not talk,” Akande narrated.

Then in 2002, after she came back from a travel, her son spoke. “ Mummy, I want my pencil,” Akande recalled the exact request her son made of her.

This was “magic”. “I was like wow, but for another six months he did not say anything.”

Akande decided to take her child out of mainstream school and teach him a skill that would transform her son’s journey.

“I got a piano teacher and the minute we started with music, my son’s life was literally changed.”

“I went to Muson centre (a centre that operates one of Nigeria’s renowned music schools) and registered him for music exams. I took their curriculum and we started working with the curriculum a step at a time.”

“A year after, I had seen a totally different boy. His voice had come back, he was talking. He was using his words, slowly but it was there. He was forming sentences, he wouldn’t use it if it is not necessary because he wasn’t the chatty type. But he will talk if it had to do with his needs. He would ask for water or food”

And these progressions inspired Akande to go for training at the national autism society in the UK.

“I took time off work as I was working as a banker while I was taking care of my autistic child.”

“I went to the national autism society in the UK and I enrolled and they gave me a series of training to go for and I started to volunteer in schools in the UK to see how they worked with the children.”

“I started to write about what autism is and the Nigerian perspective and the overwhelming response I got was unbelievable.

“A lot of people needed the service. We opened up the centre, we needed funding and GTbank supported us and we gave birth to Patrick in September of 2006.”

The centre started with three children but has seen 500 children with a maximum enrolment of 48 at any given school term.

The Patrick speech and language centre, according to Akande, caters exclusively to children with special needs.

And this is strategically so as Akande thinks children on the spectrum may struggle in mainstream schools.

“It is possible that a child on the autism spectrum will do worse in a mainstream school because they child will be overstimulated and the focus of that child will be on sensory.

“So the child is trying to cope in that ever busy environment and the child is constantly focusing on coping with his (overactive) sensory for the six hours he is in his school and not learning anything,” Akande says.

Akande’s observation is real in the Nigerian education setting where inclusive education is still largely new, under-researched and not utilised even in expensive private schools as can be seen in the way teachers tried to isolate Peter’s child.

Inclusive education, according to UNESCO, “involves the transformation of schools and other centres of learning to cater for all children – including boys and girls, students from ethnic and linguistic minorities, rural populations, those affected by HIV and AIDS, and those with disabilities and difficulties in learning”.

For instance, in inclusive schools, children with no known disability are blended with children with special needs who may have a personal aide at certain or all times to help with learning.

Inclusive schools use the differentiation strategy, which is not just grouping children into low, medium and high performing groups, but tailoring lessons, as opposed to the student’s goals, enable children reach their maximum potential.

To be fair, inclusive education is still a worldwide problem with several countries struggling to perfect inclusion in their systems.

According to UNESCO, “Ensuring that each individual has an equal opportunity for educational progress remains a challenge worldwide,” even though the UNESCO Convention against Discrimination in Education (1960) prohibit exclusion or limitation to, education “on the basis of socially-ascribed or perceived differences, such as by sex, ethnic/social origin, language, religion, nationality, economic condition, ability.”

In Nigeria, the story can get as gory as kids being treated shabbily: from a starry-eyed six-year-old innocently telling this reporter of how his teacher “knocked a special needs child for screaming his friend’s name in class” to teachers asking other children not to associate with kids on the autism spectrum.

From the perspective of an autism advocate, Peters says teachers in Nigeria have no training on including children with special needs hence the idea that they need to separate the child from their peers and encouraging segregation.

One mother who spoke on the condition of anonymity said, “teachers in my son’s school have a difficult time tailoring my child’s lessons to his high performing literacy and numeracy needs, and his yet to be unleashed art needs that are currently non-existent; talk more about tailoring a lesson to the needs of a child on the autism spectrum. It is appalling. There is a one lesson fits all strategy when children are as different as they come”.

Akande says to avoid exclusion, a child is allowed to go into a mainstream school when the Patrick Centre observes speech development, the ability to tolerate the person next to him, and has the ability to learn academically in classrooms routines.

Besides the children whose parents pull them out at the slightest sign of progression, Akande says “90 percent of children who have been in Patrick’s have gone into mainstream school and succeeded totally. unassisted. unguided.”

“It doesn’t mean they won’t have challenges in terms of coping skills. They will still need coping mechanism. One of children still needs to hold a pencil to draw to help him de-stress. some of them will still need to rock, but they learn to rock in their own room.”

“If parents let us do what we are supposed to do, there will be successes. We have witnessed retrogression when a child went into a mainstream school because the child’s parent pulled him out when the child was able to say the letter sounds”.

“We then had to start from square one.”

Akande says it is a myth that children on the spectrum will remain the same and will not progress.

“Not all children with autism will talk, but some will talk,” she says.

“All children with autism are not the same. There are different degrees, different diagnosis and different types of autism and different degrees – mild, moderate, severe.”

She says children with the severe form of autism have “no speech, no cognitive development, no language, no means of communication, high behavioural challenges and medical difficulties.”

“The moderate have behavioural issues, they sometimes do not have learning difficulties and usually do not have speech at the beginning. They are hyperactive and not attentive.

“The mild are the ones with speech, they learn, but they have no social skills.”

“All three levels are socially awkward, have no attention span, and can behave erratically. Some of them are flapping, looking at the corner of their eyes, walking on their tippy toes. Some don’t want to wear clothes because their sensory issues are very high. Some are overly sensitive to sounds or lights and it comes in various degrees”

Akande, Peters and Oguntayo speak about the infrastructural challenges in the management of autism in Nigeria in not so glowing terms.

“There is is limited infrastructure and government assistance. First of all we were the first to start a centre for the management of autism,” Akande says.

“For a child to get admission, it is not child’s play. You need 450, 000 naira a term. That is a lot.”

“What have we done is to give full scholarships to 15 15 children. We usually have a fundraising programme and we have done this four ten years now.”

“When we saw we couldn’t afford free services again, we started a consultation service where parents came to learn what resources to use and how to help their children. “

“We got a hundred and forty-something parents. There is a high demand of children with special needs that the government is not catering for, even though Lagos state now has a support fund for people living with a disability.”

As a special need interventionist, Oguntayo says even accessing resources geared towards learning is hard.

“We don’t even have a resource centre geared toward learning with a disability. There is practically nothing available.”

“As interventionists, we improvise and most of what we know are what we gain from trainings outside of the country or online. Resources needed are imported or adapted because we don’t have most of the sensory resources. We import things as minute as sensory brushes or we make do with ordinary brushes.”

Peters laments the situation. She says “it is hard! There are no governing bodies, there’s no one to tell you about a list of certified speech therapist, certified occupational therapist, certified behavioural therapist. Everyone is busy with something else and it is hard for you to evaluate what you’re doing. The schools didn’t help, the school’s system don’t help.

“I mean we class ourselves as middle-class Nigerians so (imagine) what’s happening to the lower class? They won’t even be diagnosed, they won’t get any help. There is no government infrastructure that helps.

“In the UK, they have specialists in schools, they help in public schools. They have special needs schools and they have integration.”

“In our country, we are good people but we are almost completely ignorant. We don’t know what to do, we haven’t made any plans for this situation.”

“I have been to places where there’s special playroom for children on the spectrum with sensory walls for them to touch, bouncing balls for them to bounce”, says Peters.

She says there a lot to be done which is why she and her team organises the Zumbathon for Autism awareness and funding. Her plan is to get certified trainers come into Nigeria and train teachers on inclusion and helping children with autism thrive. The plan is to get the trainers to train teachers in all schools, not just elitist ones, so all children on the spectrum can get an education.

“It is a lot to do. I don’t want to quit my day job but I want to help.”

This project was done with support from Code for Africa.

Data credit: Code for Africa